For the 22nd consecutive season, the ZiPS projection system is unleashing a full set of prognostications. For more information on the ZiPS projections, please consult this year’s introduction, as well as MLB’s glossary entry. The team order is selected by lot, and the next team up is the Arizona Diamondbacks.

Batters

Buoyant with last offseason’s Corbin Burnes signing, the Diamondbacks looked poised to return to the playoffs this season after a disappointing follow-up to their 2023 pennant, but it never quite came together. There were plenty of exciting developments, none more than Geraldo Perdomo’s breakout performance, for which he finished fourth in the NL MVP race. But Arizona lost Burnes to injury early, the rotation on the whole was mediocre, and there were a few big holes in the lineup that the team’s stars couldn’t overcome. While the D-backs did hang around in the Wild Card race into the final weeks of the season, they never really coded as a contender, and ended the season right around the .500 mark.

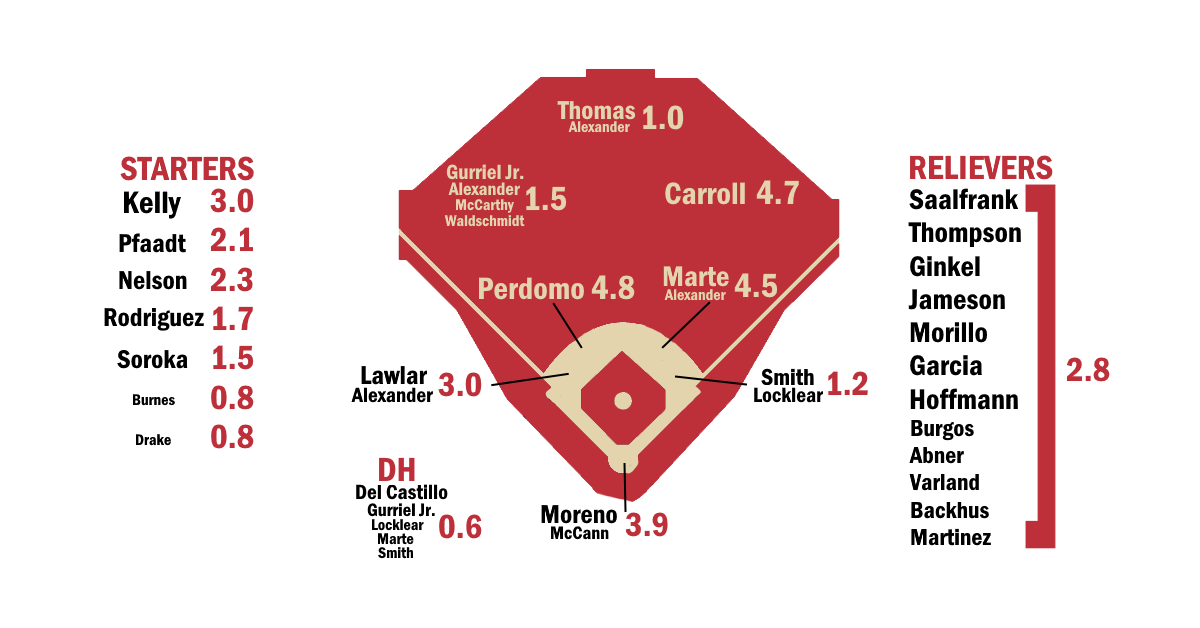

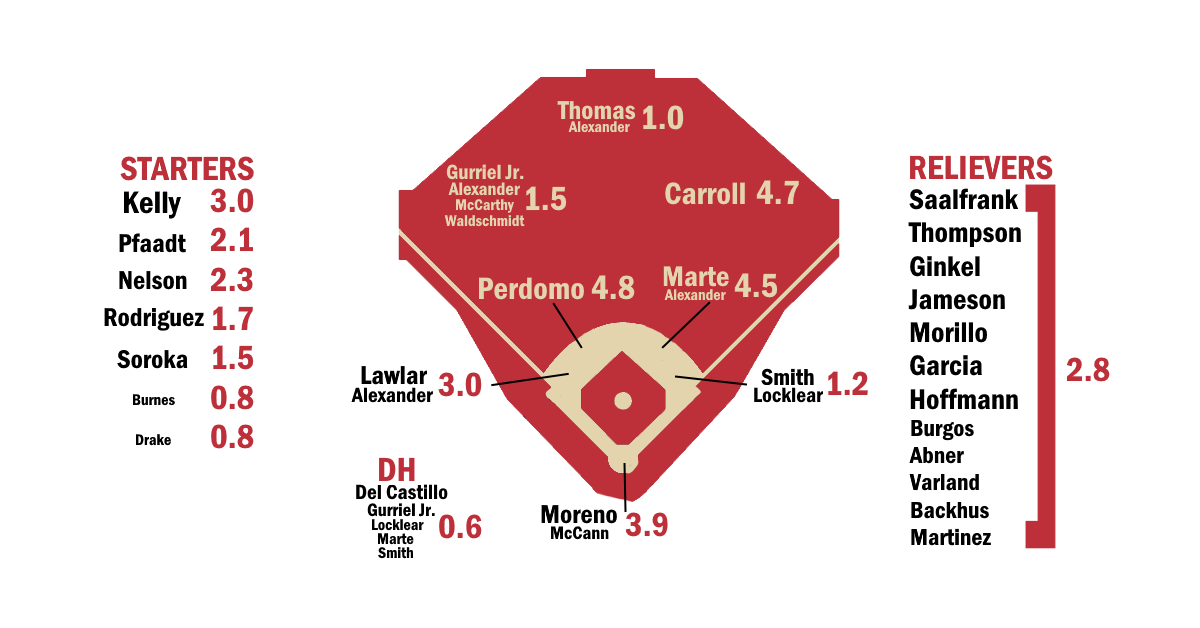

It’s amusing to look at the depth chart graphic and see just how polarizing ZiPS sees Arizona’s on-paper lineup right now. There are four positions ZiPS really likes — Corbin Carroll in right, Perdomo and Ketel Marte up the middle, and Gabriel Moreno behind the plate — and four positions ZiPS doesn’t like. Meanwhile, only third base, with Jordan Lawlar and Blaze Alexander, gets a neutral projection. In some aspects, this makes the Diamondbacks an easier group to upgrade because they have obvious areas in which they can to improve, but I’m not sure they’d seriously consider getting into the Kyle Tucker sweepstakes. There has been some chatter in the rumor mill about Alex Bregman as a target for Arizona, and if that’s the case, this team would certainly benefit from his addition, even if third base isn’t the biggest area of concern. Perdomo is for real, even if ZiPS isn’t projecting him to repeat his 7-WAR season, and I don’t think anyone’s surprised by Carroll, Marte, and Moreno being All-Star level talents. It’s fun to imagine Marte making a Hall of Fame run, but ZiPS thinks he’ll be short of 50 WAR when all is said and done, with a JAWS of 39, ranking him somewhere in the 30s among historical second basemen.

With Lawlar able to play the middle infield, Arizona could conceivably pull off a Marte trade for help in the outfield or in the rotation, though the return would likely have to be massive for this to move beyond idle internet discussion. ZiPS is thoroughly unimpressed with the Lourdes Gurriel Jr.-led combo in left, Alek Thomas in center, and the “whatever” currently slated to start at DH. This is a team that really could use Josh Naylor right about now! ZiPS sees little excitement in the high minors, especially as it has grown extremely bearish on Druw Jones’ ability to become a real hitter. Alexander perhaps has the most fascinating projection of anyone beyond the stars, and while he’s stretched as a shortstop, he is better at third base and has a lot of the qualities of a good supersub. He’ll certainly be a better supersub than he was as a cocktail: I tried to make a Blaze Alexander for science, consisting of Fireball cinnamon whiskey, crème de cacao, and cream in equal parts. It was terrible, though your mileage may vary; I’m also far less positive about negronis than most of the internet.

Pitchers

ZiPS sees a kind of last-hurrah season for Merrill Kelly, and it’s something Arizona needs with Zac Gallen perhaps departing in free agency and Burnes expectd to miss the bulk of the season. Kelly is a lot older than he seems, by virtue of debuting as a 30-year-old rookie who had to go to the KBO to become a quality pitcher. Brandon Pfaadt gets an OK projection, but ZiPS is souring on him enough that if he again greatly underperforms his peripherals, it may turn on him altogether.

The projections see some regression toward the mean for Ryne Nelson, but ZiPS still considers him a viable mid-rotation starter. Eduardo Rodriguez is projected to bounce back a bit after two rough years with Arizona, but like Pfaadt, he’s running out of time to make good on the silicon positivity. ZiPS isn’t enthusiastic about Michael Soroka, but it actually gave him a better projection than I expected.

Of the fringier pitchers that ZiPS likes, Arizona has two of the ones with better projections, in Mitch Bratt and Daniel Eagen. Bratt is a command guy, and though ZiPS knows to be skeptical of those pitchers in the minors, his control may be just good enough; he also misses bats at a high enough rate that he might thread that needle. Eagen has a couple good breaking pitches, and if the walks don’t shoot up with more time in the high minors, he may be a reasonable option in the not too distant future.

ZiPS is generally more positive about the frontend of the Diamondbacks bullpen than Steamer. The quartet of Andrew Saalfrank, Ryan Thompson, Kevin Ginkel, and Drey Jameson get a solid set of projections. The computer is also hopeful about a Justin Martinez comeback. The numbers are less positive for the second and third tier of the pen, with the exception of Kyle Backhus, who gets nearly as good a projection as any of Arizona’s other options, including Thompson and Ginkel.

Right now, the Diamondbacks are projected to be few wins better than they were this season. That puts them firmly in the Wild Card race, but ZiPS sees them as being well behind the Dodgers in the NL West, with the Giants also ahead of them. Success for Arizona also requires some of these pitching questions to be answered in a positive manner, and that’s naturally something you can’t always count on.

Ballpark graphic courtesy Eephus League. Depth charts constructed by way of those listed here. Size of player names is very roughly proportional to Depth Chart playing time. The final team projections may differ considerably from our Depth Chart playing time.

Batters – Standard

| Player |

B |

Age |

PO |

PA |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

BB |

SO |

SB |

CS |

| Corbin Carroll |

L |

25 |

RF |

661 |

574 |

112 |

147 |

27 |

13 |

27 |

92 |

70 |

140 |

35 |

6 |

| Ketel Marte |

B |

32 |

2B |

563 |

490 |

81 |

131 |

26 |

3 |

24 |

78 |

62 |

91 |

5 |

1 |

| Geraldo Perdomo |

B |

26 |

SS |

603 |

504 |

86 |

132 |

25 |

4 |

13 |

68 |

74 |

76 |

20 |

5 |

| Gabriel Moreno |

R |

26 |

C |

367 |

327 |

44 |

91 |

16 |

1 |

9 |

45 |

34 |

62 |

3 |

2 |

| Blaze Alexander |

R |

27 |

3B |

459 |

401 |

48 |

95 |

19 |

2 |

10 |

53 |

40 |

136 |

8 |

5 |

| Jordan Lawlar |

R |

23 |

SS |

421 |

375 |

54 |

87 |

22 |

3 |

9 |

46 |

36 |

111 |

17 |

3 |

| Jake McCarthy |

L |

28 |

LF |

473 |

427 |

59 |

110 |

18 |

7 |

7 |

49 |

31 |

80 |

20 |

4 |

| Lourdes Gurriel Jr. |

R |

32 |

LF |

519 |

478 |

55 |

126 |

24 |

2 |

16 |

67 |

30 |

80 |

7 |

2 |

| Tyler Locklear |

R |

25 |

1B |

525 |

466 |

64 |

116 |

24 |

3 |

14 |

70 |

42 |

131 |

11 |

3 |

| Jorge Barrosa |

B |

25 |

CF |

509 |

456 |

56 |

102 |

22 |

3 |

7 |

47 |

43 |

115 |

9 |

5 |

| LuJames Groover |

R |

24 |

3B |

531 |

479 |

48 |

119 |

25 |

0 |

8 |

57 |

41 |

89 |

2 |

2 |

| Tommy Troy |

R |

24 |

2B |

523 |

468 |

51 |

108 |

21 |

3 |

8 |

52 |

42 |

112 |

13 |

4 |

| Alek Thomas |

L |

26 |

CF |

466 |

429 |

55 |

103 |

19 |

4 |

10 |

47 |

25 |

103 |

7 |

3 |

| Ildemaro Vargas |

B |

34 |

3B |

336 |

310 |

30 |

75 |

13 |

2 |

4 |

36 |

19 |

37 |

3 |

1 |

| Ryan Waldschmidt |

R |

23 |

LF |

588 |

507 |

76 |

117 |

21 |

3 |

10 |

65 |

64 |

124 |

15 |

7 |

| Cristofer Torin |

R |

21 |

SS |

580 |

521 |

66 |

122 |

21 |

2 |

4 |

48 |

49 |

103 |

9 |

5 |

| Tim Tawa |

R |

27 |

2B |

454 |

410 |

49 |

89 |

17 |

2 |

12 |

47 |

36 |

114 |

9 |

4 |

| Pavin Smith |

L |

30 |

DH |

386 |

334 |

44 |

79 |

17 |

1 |

11 |

45 |

48 |

98 |

2 |

1 |

| Grae Kessinger |

R |

28 |

SS |

318 |

278 |

40 |

61 |

11 |

1 |

5 |

28 |

33 |

81 |

5 |

3 |

| Demetrio Crisantes |

R |

21 |

2B |

319 |

287 |

40 |

69 |

13 |

2 |

5 |

33 |

25 |

55 |

9 |

2 |

| Sergio Alcántara |

B |

29 |

SS |

428 |

375 |

45 |

83 |

16 |

3 |

3 |

36 |

46 |

97 |

2 |

2 |

| Christian Cerda |

R |

23 |

C |

427 |

371 |

36 |

78 |

15 |

0 |

8 |

39 |

45 |

94 |

1 |

0 |

| Jacob Amaya |

R |

27 |

SS |

417 |

372 |

44 |

79 |

13 |

2 |

7 |

42 |

38 |

107 |

5 |

2 |

| Matt Mervis |

L |

28 |

1B |

436 |

395 |

50 |

88 |

19 |

2 |

17 |

61 |

32 |

124 |

3 |

1 |

| Tristin English |

R |

29 |

1B |

440 |

408 |

44 |

100 |

19 |

1 |

10 |

52 |

23 |

93 |

1 |

1 |

| James McCann |

R |

36 |

C |

254 |

233 |

26 |

55 |

13 |

0 |

6 |

28 |

13 |

66 |

1 |

0 |

| Aramis Garcia |

R |

33 |

C |

264 |

239 |

27 |

48 |

8 |

0 |

7 |

27 |

19 |

92 |

1 |

0 |

| Seth Brown |

L |

33 |

1B |

355 |

324 |

35 |

77 |

14 |

2 |

14 |

50 |

28 |

92 |

3 |

1 |

| Druw Jones |

R |

22 |

CF |

562 |

515 |

63 |

115 |

22 |

4 |

4 |

47 |

38 |

158 |

17 |

3 |

| Jansel Luis |

B |

21 |

2B |

506 |

473 |

56 |

116 |

20 |

7 |

4 |

48 |

21 |

104 |

13 |

6 |

| A.J. Vukovich |

R |

24 |

LF |

506 |

469 |

55 |

108 |

19 |

3 |

13 |

55 |

32 |

158 |

5 |

3 |

| Cristian Pache |

R |

27 |

RF |

286 |

257 |

26 |

55 |

10 |

2 |

3 |

26 |

24 |

87 |

4 |

2 |

| Andy Weber |

L |

28 |

2B |

446 |

412 |

50 |

100 |

17 |

3 |

4 |

40 |

28 |

95 |

2 |

4 |

| Ben McLaughlin |

L |

24 |

1B |

377 |

331 |

31 |

74 |

19 |

0 |

5 |

35 |

40 |

87 |

0 |

1 |

| Danny Serretti |

B |

26 |

3B |

334 |

297 |

32 |

61 |

13 |

1 |

4 |

32 |

29 |

86 |

3 |

2 |

| Trey Mancini |

R |

34 |

1B |

337 |

306 |

37 |

72 |

14 |

0 |

9 |

39 |

22 |

87 |

1 |

0 |

| Michael Pérez |

L |

33 |

C |

235 |

211 |

22 |

40 |

10 |

0 |

4 |

25 |

16 |

68 |

6 |

2 |

| Albert Almora Jr. |

R |

32 |

CF |

381 |

351 |

40 |

84 |

18 |

2 |

4 |

36 |

22 |

70 |

7 |

4 |

| Adrian Del Castillo |

L |

26 |

DH |

413 |

373 |

43 |

84 |

18 |

2 |

12 |

51 |

34 |

118 |

1 |

0 |

| Matt O’Neill |

R |

28 |

C |

200 |

178 |

20 |

33 |

6 |

1 |

3 |

16 |

20 |

68 |

0 |

1 |

| Ivan Melendez |

R |

26 |

1B |

411 |

375 |

36 |

80 |

12 |

1 |

12 |

51 |

25 |

132 |

1 |

1 |

| Kristian Robinson |

R |

25 |

CF |

472 |

417 |

48 |

87 |

14 |

3 |

9 |

46 |

49 |

165 |

16 |

5 |

| Kenny Castillo |

R |

22 |

C |

318 |

298 |

23 |

65 |

15 |

1 |

3 |

28 |

12 |

81 |

0 |

0 |

| Jesus Valdez |

R |

28 |

3B |

261 |

245 |

25 |

52 |

9 |

1 |

5 |

25 |

12 |

81 |

1 |

3 |

| Jean Walters |

B |

24 |

2B |

302 |

274 |

26 |

57 |

9 |

3 |

2 |

21 |

15 |

73 |

2 |

2 |

| J.J. D’Orazio |

R |

24 |

C |

323 |

300 |

24 |

64 |

13 |

1 |

2 |

25 |

18 |

86 |

1 |

1 |

| Gavin Logan |

L |

26 |

C |

251 |

222 |

19 |

39 |

9 |

2 |

4 |

23 |

22 |

95 |

1 |

1 |

| Cole Roberts |

R |

25 |

2B |

121 |

107 |

11 |

20 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

10 |

25 |

2 |

1 |

| Manuel Pena |

L |

22 |

1B |

500 |

472 |

47 |

114 |

24 |

2 |

6 |

48 |

21 |

130 |

2 |

4 |

| Slade Caldwell |

L |

20 |

CF |

542 |

468 |

67 |

91 |

26 |

2 |

2 |

47 |

59 |

172 |

12 |

7 |

| Adrian De Leon |

R |

22 |

C |

328 |

284 |

25 |

45 |

11 |

0 |

3 |

25 |

29 |

115 |

1 |

1 |

| Angel Ortiz |

L |

23 |

RF |

490 |

449 |

48 |

103 |

22 |

4 |

7 |

48 |

30 |

114 |

2 |

3 |

| Junior Franco |

L |

23 |

LF |

332 |

309 |

30 |

70 |

11 |

2 |

5 |

32 |

20 |

65 |

9 |

5 |

| Jose Fernandez |

R |

22 |

SS |

508 |

479 |

47 |

108 |

17 |

3 |

8 |

49 |

21 |

123 |

7 |

3 |

| Gavin Conticello |

L |

23 |

RF |

534 |

488 |

48 |

107 |

23 |

4 |

8 |

53 |

38 |

135 |

5 |

4 |

| Jackson Feltner |

R |

24 |

1B |

254 |

225 |

23 |

38 |

7 |

1 |

6 |

26 |

21 |

103 |

0 |

1 |

| Anderdson Rojas |

L |

22 |

3B |

490 |

443 |

52 |

92 |

15 |

3 |

2 |

34 |

30 |

95 |

13 |

6 |

| Adrian Rodriguez |

R |

22 |

SS |

340 |

305 |

31 |

55 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

24 |

25 |

105 |

2 |

3 |

| Modeifi Marte |

R |

23 |

1B |

373 |

345 |

31 |

77 |

15 |

1 |

3 |

32 |

21 |

74 |

4 |

2 |

| Kevin Graham |

L |

26 |

LF |

258 |

237 |

22 |

43 |

9 |

1 |

3 |

19 |

17 |

88 |

2 |

1 |

| Caleb Roberts |

L |

26 |

LF |

454 |

408 |

44 |

83 |

17 |

4 |

7 |

45 |

36 |

130 |

5 |

2 |

| Jack Hurley |

L |

24 |

CF |

383 |

355 |

35 |

68 |

14 |

3 |

6 |

36 |

19 |

163 |

3 |

5 |

| Juan Corniel |

B |

23 |

SS |

332 |

305 |

30 |

58 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

22 |

17 |

85 |

4 |

6 |

| Ruben Santana |

R |

21 |

1B |

465 |

423 |

38 |

78 |

13 |

2 |

5 |

37 |

33 |

146 |

8 |

1 |

Batters – Advanced

| Player |

PA |

BA |

OBP |

SLG |

OPS+ |

ISO |

BABIP |

Def |

WAR |

wOBA |

3YOPS+ |

RC |

| Corbin Carroll |

661 |

.256 |

.344 |

.490 |

128 |

.234 |

.295 |

7 |

4.8 |

.356 |

129 |

106 |

| Ketel Marte |

563 |

.267 |

.353 |

.480 |

129 |

.213 |

.285 |

1 |

4.2 |

.356 |

120 |

84 |

| Geraldo Perdomo |

603 |

.262 |

.361 |

.405 |

112 |

.143 |

.287 |

2 |

4.1 |

.337 |

112 |

80 |

| Gabriel Moreno |

367 |

.278 |

.349 |

.416 |

111 |

.138 |

.320 |

8 |

3.1 |

.333 |

111 |

49 |

| Blaze Alexander |

459 |

.237 |

.322 |

.369 |

92 |

.132 |

.333 |

7 |

2.0 |

.307 |

93 |

51 |

| Jordan Lawlar |

421 |

.232 |

.308 |

.379 |

89 |

.147 |

.306 |

1 |

1.7 |

.301 |

93 |

48 |

| Jake McCarthy |

473 |

.258 |

.320 |

.382 |

94 |

.124 |

.303 |

4 |

1.4 |

.308 |

93 |

58 |

| Lourdes Gurriel Jr. |

519 |

.264 |

.312 |

.423 |

102 |

.159 |

.288 |

1 |

1.3 |

.317 |

95 |

65 |

| Tyler Locklear |

525 |

.249 |

.328 |

.403 |

102 |

.154 |

.318 |

0 |

1.2 |

.320 |

102 |

65 |

| Jorge Barrosa |

509 |

.224 |

.293 |

.331 |

73 |

.107 |

.284 |

7 |

1.0 |

.277 |

75 |

48 |

| LuJames Groover |

531 |

.248 |

.316 |

.351 |

85 |

.103 |

.291 |

0 |

1.0 |

.296 |

88 |

54 |

| Tommy Troy |

523 |

.231 |

.301 |

.340 |

78 |

.109 |

.287 |

1 |

0.9 |

.285 |

81 |

52 |

| Alek Thomas |

466 |

.240 |

.286 |

.373 |

81 |

.133 |

.294 |

2 |

0.9 |

.287 |

83 |

48 |

| Ildemaro Vargas |

336 |

.242 |

.290 |

.335 |

73 |

.094 |

.264 |

6 |

0.8 |

.276 |

71 |

31 |

| Ryan Waldschmidt |

588 |

.231 |

.330 |

.343 |

88 |

.112 |

.287 |

1 |

0.7 |

.302 |

91 |

63 |

| Cristofer Torin |

580 |

.234 |

.304 |

.305 |

70 |

.071 |

.285 |

1 |

0.7 |

.275 |

73 |

52 |

| Tim Tawa |

454 |

.217 |

.285 |

.356 |

77 |

.139 |

.271 |

3 |

0.7 |

.282 |

75 |

45 |

| Pavin Smith |

386 |

.237 |

.332 |

.392 |

100 |

.155 |

.302 |

0 |

0.7 |

.318 |

98 |

44 |

| Grae Kessinger |

318 |

.219 |

.306 |

.320 |

74 |

.101 |

.292 |

2 |

0.7 |

.282 |

75 |

29 |

| Demetrio Crisantes |

319 |

.240 |

.307 |

.352 |

83 |

.111 |

.282 |

0 |

0.7 |

.292 |

86 |

34 |

| Sergio Alcántara |

428 |

.221 |

.308 |

.304 |

71 |

.083 |

.291 |

1 |

0.6 |

.277 |

72 |

36 |

| Christian Cerda |

427 |

.210 |

.298 |

.315 |

71 |

.105 |

.260 |

-1 |

0.6 |

.276 |

74 |

35 |

| Jacob Amaya |

417 |

.212 |

.286 |

.315 |

67 |

.102 |

.279 |

2 |

0.5 |

.268 |

68 |

35 |

| Matt Mervis |

436 |

.223 |

.289 |

.410 |

91 |

.187 |

.280 |

2 |

0.5 |

.302 |

91 |

48 |

| Tristin English |

440 |

.245 |

.295 |

.370 |

83 |

.125 |

.295 |

5 |

0.4 |

.292 |

83 |

45 |

| James McCann |

254 |

.236 |

.285 |

.369 |

80 |

.133 |

.304 |

-2 |

0.4 |

.285 |

76 |

25 |

| Aramis Garcia |

264 |

.201 |

.269 |

.322 |

63 |

.121 |

.293 |

3 |

0.4 |

.263 |

59 |

21 |

| Seth Brown |

355 |

.238 |

.301 |

.423 |

98 |

.185 |

.289 |

-2 |

0.3 |

.313 |

92 |

42 |

| Druw Jones |

562 |

.223 |

.279 |

.305 |

62 |

.082 |

.314 |

5 |

0.2 |

.260 |

65 |

48 |

| Jansel Luis |

506 |

.245 |

.282 |

.342 |

73 |

.097 |

.307 |

1 |

0.2 |

.273 |

76 |

51 |

| A.J. Vukovich |

506 |

.230 |

.283 |

.367 |

79 |

.137 |

.319 |

5 |

0.2 |

.283 |

82 |

51 |

| Cristian Pache |

286 |

.214 |

.285 |

.304 |

64 |

.090 |

.311 |

8 |

0.2 |

.264 |

67 |

24 |

| Andy Weber |

446 |

.243 |

.293 |

.328 |

72 |

.085 |

.307 |

1 |

0.2 |

.275 |

73 |

42 |

| Ben McLaughlin |

377 |

.224 |

.311 |

.326 |

78 |

.102 |

.289 |

4 |

0.1 |

.287 |

81 |

34 |

| Danny Serretti |

334 |

.205 |

.282 |

.296 |

62 |

.091 |

.275 |

5 |

0.1 |

.261 |

65 |

26 |

| Trey Mancini |

337 |

.235 |

.297 |

.369 |

84 |

.134 |

.300 |

0 |

-0.1 |

.290 |

79 |

34 |

| Michael Pérez |

235 |

.190 |

.268 |

.294 |

56 |

.104 |

.259 |

-1 |

-0.1 |

.254 |

56 |

19 |

| Albert Almora Jr. |

381 |

.239 |

.288 |

.336 |

73 |

.097 |

.289 |

-2 |

-0.1 |

.276 |

71 |

37 |

| Adrian Del Castillo |

413 |

.225 |

.293 |

.381 |

85 |

.156 |

.296 |

0 |

-0.1 |

.294 |

89 |

42 |

| Matt O’Neill |

200 |

.185 |

.270 |

.281 |

54 |

.096 |

.280 |

0 |

-0.2 |

.250 |

54 |

14 |

| Ivan Melendez |

411 |

.213 |

.277 |

.347 |

72 |

.134 |

.294 |

5 |

-0.2 |

.276 |

76 |

37 |

| Kristian Robinson |

472 |

.209 |

.297 |

.321 |

72 |

.112 |

.321 |

-6 |

-0.3 |

.277 |

76 |

45 |

| Kenny Castillo |

318 |

.218 |

.249 |

.305 |

53 |

.087 |

.290 |

0 |

-0.4 |

.242 |

58 |

23 |

| Jesus Valdez |

261 |

.212 |

.253 |

.318 |

57 |

.106 |

.296 |

1 |

-0.5 |

.251 |

57 |

21 |

| Jean Walters |

302 |

.208 |

.251 |

.285 |

49 |

.077 |

.276 |

3 |

-0.5 |

.237 |

50 |

21 |

| J.J. D’Orazio |

323 |

.213 |

.261 |

.283 |

51 |

.070 |

.292 |

-1 |

-0.5 |

.243 |

55 |

23 |

| Gavin Logan |

251 |

.176 |

.261 |

.288 |

53 |

.112 |

.285 |

-3 |

-0.5 |

.248 |

57 |

17 |

| Cole Roberts |

121 |

.187 |

.254 |

.206 |

30 |

.019 |

.244 |

-1 |

-0.6 |

.214 |

29 |

6 |

| Manuel Pena |

500 |

.242 |

.277 |

.339 |

70 |

.097 |

.321 |

5 |

-0.7 |

.269 |

73 |

46 |

| Slade Caldwell |

542 |

.194 |

.298 |

.271 |

60 |

.077 |

.303 |

-3 |

-0.7 |

.262 |

67 |

43 |

| Adrian De Leon |

328 |

.158 |

.255 |

.229 |

36 |

.071 |

.253 |

1 |

-0.8 |

.226 |

41 |

17 |

| Angel Ortiz |

490 |

.229 |

.280 |

.343 |

72 |

.114 |

.293 |

0 |

-0.8 |

.273 |

77 |

45 |

| Junior Franco |

332 |

.227 |

.277 |

.324 |

66 |

.097 |

.272 |

-2 |

-0.9 |

.266 |

71 |

32 |

| Jose Fernandez |

508 |

.225 |

.262 |

.324 |

62 |

.099 |

.287 |

-7 |

-0.9 |

.257 |

67 |

43 |

| Gavin Conticello |

534 |

.219 |

.283 |

.332 |

70 |

.113 |

.287 |

-1 |

-1.0 |

.272 |

75 |

49 |

| Jackson Feltner |

254 |

.169 |

.257 |

.289 |

51 |

.120 |

.276 |

0 |

-1.1 |

.247 |

54 |

17 |

| Anderdson Rojas |

490 |

.208 |

.259 |

.269 |

47 |

.061 |

.260 |

3 |

-1.2 |

.237 |

51 |

36 |

| Adrian Rodriguez |

340 |

.180 |

.254 |

.223 |

34 |

.043 |

.271 |

0 |

-1.2 |

.222 |

41 |

19 |

| Modeifi Marte |

373 |

.223 |

.273 |

.299 |

59 |

.076 |

.276 |

0 |

-1.3 |

.254 |

62 |

30 |

| Kevin Graham |

258 |

.181 |

.240 |

.266 |

41 |

.085 |

.274 |

1 |

-1.3 |

.227 |

43 |

16 |

| Caleb Roberts |

454 |

.203 |

.278 |

.316 |

65 |

.113 |

.280 |

-4 |

-1.4 |

.264 |

68 |

38 |

| Jack Hurley |

383 |

.192 |

.241 |

.299 |

49 |

.107 |

.333 |

-3 |

-1.5 |

.238 |

54 |

28 |

| Juan Corniel |

332 |

.190 |

.239 |

.239 |

34 |

.049 |

.260 |

-2 |

-1.6 |

.217 |

38 |

21 |

| Ruben Santana |

465 |

.184 |

.252 |

.260 |

43 |

.076 |

.268 |

4 |

-2.0 |

.231 |

51 |

30 |

Batters – Top Near-Age Offensive Comps

Batters – 80th/20th Percentiles

| Player |

80th BA |

80th OBP |

80th SLG |

80th OPS+ |

80th WAR |

20th BA |

20th OBP |

20th SLG |

20th OPS+ |

20th WAR |

| Corbin Carroll |

.283 |

.371 |

.548 |

150 |

6.4 |

.230 |

.318 |

.425 |

107 |

2.9 |

| Ketel Marte |

.292 |

.382 |

.540 |

148 |

5.6 |

.242 |

.329 |

.435 |

110 |

2.9 |

| Geraldo Perdomo |

.291 |

.390 |

.457 |

133 |

5.7 |

.242 |

.335 |

.362 |

95 |

2.8 |

| Gabriel Moreno |

.311 |

.379 |

.467 |

133 |

4.0 |

.250 |

.320 |

.371 |

93 |

2.2 |

| Blaze Alexander |

.265 |

.350 |

.420 |

111 |

3.2 |

.209 |

.295 |

.321 |

71 |

0.9 |

| Jordan Lawlar |

.263 |

.333 |

.435 |

109 |

2.7 |

.209 |

.285 |

.332 |

70 |

0.7 |

| Jake McCarthy |

.288 |

.346 |

.431 |

114 |

2.6 |

.231 |

.288 |

.330 |

76 |

0.2 |

| Lourdes Gurriel Jr. |

.288 |

.336 |

.469 |

118 |

2.4 |

.235 |

.288 |

.375 |

82 |

0.1 |

| Tyler Locklear |

.279 |

.354 |

.450 |

120 |

2.4 |

.223 |

.304 |

.355 |

84 |

0.1 |

| Jorge Barrosa |

.248 |

.319 |

.372 |

88 |

2.0 |

.197 |

.270 |

.291 |

56 |

-0.2 |

| LuJames Groover |

.273 |

.342 |

.391 |

102 |

2.1 |

.222 |

.290 |

.311 |

68 |

-0.2 |

| Tommy Troy |

.255 |

.323 |

.378 |

94 |

1.9 |

.205 |

.276 |

.298 |

62 |

-0.2 |

| Alek Thomas |

.267 |

.313 |

.422 |

101 |

1.9 |

.214 |

.259 |

.326 |

62 |

-0.3 |

| Ildemaro Vargas |

.267 |

.319 |

.382 |

92 |

1.6 |

.211 |

.265 |

.293 |

54 |

0.0 |

| Ryan Waldschmidt |

.258 |

.357 |

.393 |

106 |

2.0 |

.206 |

.306 |

.303 |

70 |

-0.5 |

| Cristofer Torin |

.261 |

.333 |

.344 |

87 |

2.0 |

.206 |

.278 |

.266 |

52 |

-0.5 |

| Tim Tawa |

.244 |

.313 |

.409 |

97 |

1.9 |

.189 |

.260 |

.314 |

60 |

-0.2 |

| Pavin Smith |

.261 |

.357 |

.446 |

117 |

1.5 |

.204 |

.305 |

.339 |

79 |

-0.3 |

| Grae Kessinger |

.247 |

.338 |

.368 |

95 |

1.6 |

.188 |

.277 |

.274 |

55 |

-0.1 |

| Demetrio Crisantes |

.272 |

.336 |

.407 |

103 |

1.4 |

.209 |

.278 |

.308 |

63 |

-0.1 |

| Sergio Alcántara |

.251 |

.336 |

.353 |

91 |

1.6 |

.193 |

.276 |

.262 |

53 |

-0.4 |

| Christian Cerda |

.237 |

.328 |

.359 |

89 |

1.6 |

.183 |

.269 |

.267 |

51 |

-0.4 |

| Jacob Amaya |

.238 |

.312 |

.367 |

87 |

1.5 |

.183 |

.258 |

.270 |

48 |

-0.5 |

| Matt Mervis |

.247 |

.315 |

.468 |

113 |

1.6 |

.196 |

.268 |

.361 |

73 |

-0.4 |

| Tristin English |

.274 |

.324 |

.421 |

104 |

1.5 |

.218 |

.268 |

.330 |

64 |

-0.7 |

| James McCann |

.267 |

.314 |

.424 |

100 |

1.0 |

.206 |

.259 |

.322 |

62 |

-0.2 |

| Aramis Garcia |

.232 |

.302 |

.374 |

83 |

1.0 |

.175 |

.242 |

.270 |

45 |

-0.3 |

| Seth Brown |

.263 |

.325 |

.479 |

120 |

1.2 |

.210 |

.274 |

.367 |

78 |

-0.6 |

| Druw Jones |

.250 |

.303 |

.347 |

80 |

1.4 |

.194 |

.252 |

.262 |

44 |

-1.1 |

| Jansel Luis |

.274 |

.311 |

.396 |

94 |

1.6 |

.217 |

.255 |

.295 |

53 |

-1.0 |

| A.J. Vukovich |

.257 |

.308 |

.418 |

99 |

1.5 |

.202 |

.256 |

.319 |

59 |

-1.0 |

| Cristian Pache |

.245 |

.312 |

.346 |

82 |

0.8 |

.184 |

.253 |

.260 |

44 |

-0.5 |

| Andy Weber |

.273 |

.319 |

.367 |

91 |

1.3 |

.209 |

.259 |

.286 |

52 |

-1.0 |

| Ben McLaughlin |

.251 |

.340 |

.372 |

96 |

0.9 |

.197 |

.284 |

.286 |

59 |

-0.8 |

| Danny Serretti |

.234 |

.311 |

.344 |

82 |

0.9 |

.175 |

.254 |

.255 |

43 |

-0.7 |

| Trey Mancini |

.264 |

.323 |

.416 |

103 |

0.7 |

.207 |

.271 |

.326 |

65 |

-0.9 |

| Michael Pérez |

.219 |

.297 |

.341 |

74 |

0.4 |

.164 |

.242 |

.249 |

37 |

-0.8 |

| Albert Almora Jr. |

.268 |

.320 |

.384 |

94 |

0.9 |

.209 |

.260 |

.291 |

53 |

-1.1 |

| Adrian Del Castillo |

.256 |

.318 |

.432 |

105 |

0.9 |

.201 |

.269 |

.336 |

68 |

-1.0 |

| Matt O’Neill |

.218 |

.303 |

.338 |

77 |

0.4 |

.156 |

.237 |

.239 |

33 |

-0.7 |

| Ivan Melendez |

.236 |

.300 |

.392 |

91 |

0.7 |

.187 |

.253 |

.306 |

56 |

-1.1 |

| Kristian Robinson |

.236 |

.324 |

.368 |

90 |

0.7 |

.180 |

.268 |

.275 |

53 |

-1.4 |

| Kenny Castillo |

.249 |

.279 |

.347 |

71 |

0.3 |

.193 |

.225 |

.268 |

38 |

-1.0 |

| Jesus Valdez |

.242 |

.280 |

.371 |

78 |

0.2 |

.185 |

.222 |

.280 |

38 |

-1.2 |

| Jean Walters |

.239 |

.278 |

.332 |

68 |

0.2 |

.181 |

.220 |

.246 |

31 |

-1.2 |

| J.J. D’Orazio |

.243 |

.289 |

.323 |

70 |

0.2 |

.184 |

.235 |

.244 |

34 |

-1.2 |

| Gavin Logan |

.209 |

.291 |

.347 |

76 |

0.2 |

.145 |

.225 |

.241 |

32 |

-1.1 |

| Cole Roberts |

.214 |

.288 |

.241 |

48 |

-0.4 |

.160 |

.223 |

.172 |

14 |

-0.9 |

| Manuel Pena |

.268 |

.302 |

.386 |

86 |

0.4 |

.215 |

.251 |

.304 |

53 |

-1.8 |

| Slade Caldwell |

.224 |

.324 |

.314 |

78 |

0.4 |

.168 |

.271 |

.230 |

43 |

-1.8 |

| Adrian De Leon |

.185 |

.286 |

.269 |

55 |

0.0 |

.131 |

.229 |

.190 |

20 |

-1.5 |

| Angel Ortiz |

.258 |

.306 |

.384 |

88 |

0.1 |

.200 |

.252 |

.295 |

51 |

-2.2 |

| Junior Franco |

.255 |

.303 |

.372 |

84 |

-0.1 |

.199 |

.250 |

.284 |

49 |

-1.6 |

| Jose Fernandez |

.252 |

.289 |

.372 |

82 |

0.4 |

.201 |

.238 |

.285 |

45 |

-1.9 |

| Gavin Conticello |

.249 |

.310 |

.373 |

87 |

0.1 |

.193 |

.256 |

.289 |

52 |

-2.3 |

| Jackson Feltner |

.195 |

.289 |

.341 |

74 |

-0.4 |

.140 |

.233 |

.241 |

36 |

-1.6 |

| Anderdson Rojas |

.238 |

.290 |

.309 |

66 |

0.1 |

.181 |

.233 |

.227 |

28 |

-2.3 |

| Adrian Rodriguez |

.211 |

.283 |

.265 |

54 |

-0.3 |

.154 |

.223 |

.184 |

18 |

-2.0 |

| Modeifi Marte |

.248 |

.300 |

.342 |

77 |

-0.4 |

.193 |

.246 |

.257 |

41 |

-2.2 |

| Kevin Graham |

.210 |

.269 |

.313 |

61 |

-0.6 |

.157 |

.217 |

.224 |

23 |

-1.8 |

| Caleb Roberts |

.233 |

.309 |

.362 |

85 |

-0.2 |

.180 |

.257 |

.272 |

48 |

-2.3 |

| Jack Hurley |

.219 |

.267 |

.347 |

68 |

-0.6 |

.165 |

.215 |

.255 |

29 |

-2.5 |

| Juan Corniel |

.218 |

.265 |

.280 |

50 |

-0.8 |

.164 |

.213 |

.206 |

16 |

-2.3 |

| Ruben Santana |

.211 |

.278 |

.297 |

61 |

-0.9 |

.158 |

.227 |

.225 |

26 |

-3.0 |

Batters – Platoon Splits

| Player |

BA vs. L |

OBP vs. L |

SLG vs. L |

BA vs. R |

OBP vs. R |

SLG vs. R |

| Corbin Carroll |

.249 |

.330 |

.448 |

.260 |

.351 |

.509 |

| Ketel Marte |

.278 |

.356 |

.525 |

.262 |

.352 |

.458 |

| Geraldo Perdomo |

.275 |

.362 |

.412 |

.256 |

.361 |

.402 |

| Gabriel Moreno |

.291 |

.364 |

.444 |

.271 |

.340 |

.400 |

| Blaze Alexander |

.243 |

.329 |

.389 |

.233 |

.318 |

.358 |

| Jordan Lawlar |

.248 |

.326 |

.402 |

.225 |

.300 |

.368 |

| Jake McCarthy |

.248 |

.311 |

.372 |

.262 |

.324 |

.386 |

| Lourdes Gurriel Jr. |

.275 |

.325 |

.444 |

.259 |

.307 |

.414 |

| Tyler Locklear |

.250 |

.331 |

.403 |

.248 |

.326 |

.404 |

| Jorge Barrosa |

.219 |

.287 |

.323 |

.226 |

.296 |

.336 |

| LuJames Groover |

.258 |

.331 |

.377 |

.244 |

.309 |

.338 |

| Tommy Troy |

.230 |

.303 |

.351 |

.231 |

.301 |

.334 |

| Alek Thomas |

.234 |

.277 |

.359 |

.243 |

.289 |

.379 |

| Ildemaro Vargas |

.248 |

.288 |

.368 |

.238 |

.292 |

.316 |

| Ryan Waldschmidt |

.237 |

.343 |

.355 |

.228 |

.324 |

.338 |

| Cristofer Torin |

.237 |

.312 |

.309 |

.233 |

.301 |

.304 |

| Tim Tawa |

.217 |

.292 |

.364 |

.217 |

.282 |

.352 |

| Pavin Smith |

.230 |

.313 |

.345 |

.239 |

.338 |

.409 |

| Grae Kessinger |

.224 |

.317 |

.318 |

.216 |

.299 |

.322 |

| Demetrio Crisantes |

.247 |

.316 |

.388 |

.238 |

.304 |

.337 |

| Sergio Alcántara |

.215 |

.303 |

.299 |

.224 |

.309 |

.306 |

| Christian Cerda |

.211 |

.311 |

.307 |

.210 |

.292 |

.319 |

| Jacob Amaya |

.217 |

.301 |

.333 |

.209 |

.277 |

.303 |

| Matt Mervis |

.220 |

.288 |

.394 |

.224 |

.290 |

.418 |

| Tristin English |

.256 |

.306 |

.398 |

.240 |

.291 |

.356 |

| James McCann |

.247 |

.300 |

.384 |

.231 |

.277 |

.363 |

| Aramis Garcia |

.221 |

.291 |

.338 |

.191 |

.258 |

.315 |

| Seth Brown |

.229 |

.299 |

.357 |

.240 |

.302 |

.441 |

| Druw Jones |

.221 |

.283 |

.297 |

.224 |

.277 |

.308 |

| Jansel Luis |

.246 |

.282 |

.343 |

.245 |

.283 |

.342 |

| A.J. Vukovich |

.232 |

.287 |

.364 |

.230 |

.281 |

.368 |

| Cristian Pache |

.234 |

.311 |

.355 |

.200 |

.267 |

.267 |

| Andy Weber |

.228 |

.272 |

.307 |

.249 |

.302 |

.337 |

| Ben McLaughlin |

.222 |

.297 |

.311 |

.224 |

.316 |

.332 |

| Danny Serretti |

.207 |

.278 |

.287 |

.205 |

.284 |

.300 |

| Trey Mancini |

.232 |

.300 |

.374 |

.237 |

.295 |

.367 |

| Michael Pérez |

.196 |

.281 |

.294 |

.188 |

.264 |

.294 |

| Albert Almora Jr. |

.250 |

.303 |

.348 |

.234 |

.281 |

.331 |

| Adrian Del Castillo |

.220 |

.277 |

.367 |

.227 |

.299 |

.386 |

| Matt O’Neill |

.186 |

.284 |

.271 |

.185 |

.263 |

.286 |

| Ivan Melendez |

.219 |

.286 |

.360 |

.211 |

.274 |

.341 |

| Kristian Robinson |

.214 |

.310 |

.341 |

.206 |

.291 |

.313 |

| Kenny Castillo |

.228 |

.255 |

.315 |

.214 |

.247 |

.301 |

| Jesus Valdez |

.215 |

.259 |

.329 |

.211 |

.250 |

.313 |

| Jean Walters |

.209 |

.253 |

.302 |

.207 |

.250 |

.277 |

| J.J. D’Orazio |

.216 |

.274 |

.299 |

.212 |

.255 |

.276 |

| Gavin Logan |

.164 |

.250 |

.279 |

.180 |

.265 |

.292 |

| Cole Roberts |

.176 |

.263 |

.206 |

.192 |

.250 |

.205 |

| Manuel Pena |

.231 |

.265 |

.329 |

.246 |

.282 |

.343 |

| Slade Caldwell |

.189 |

.285 |

.250 |

.196 |

.303 |

.280 |

| Adrian De Leon |

.163 |

.263 |

.244 |

.157 |

.252 |

.222 |

| Angel Ortiz |

.224 |

.272 |

.328 |

.231 |

.283 |

.349 |

| Junior Franco |

.221 |

.267 |

.305 |

.229 |

.281 |

.332 |

| Jose Fernandez |

.237 |

.279 |

.346 |

.220 |

.254 |

.313 |

| Gavin Conticello |

.209 |

.270 |

.309 |

.223 |

.288 |

.341 |

| Jackson Feltner |

.174 |

.269 |

.290 |

.167 |

.251 |

.288 |

| Anderdson Rojas |

.191 |

.236 |

.235 |

.213 |

.267 |

.280 |

| Adrian Rodriguez |

.189 |

.264 |

.232 |

.176 |

.250 |

.219 |

| Modeifi Marte |

.224 |

.276 |

.299 |

.223 |

.272 |

.298 |

| Kevin Graham |

.169 |

.225 |

.246 |

.186 |

.246 |

.273 |

| Caleb Roberts |

.192 |

.263 |

.292 |

.208 |

.283 |

.326 |

| Jack Hurley |

.190 |

.241 |

.300 |

.192 |

.241 |

.298 |

| Juan Corniel |

.186 |

.231 |

.216 |

.192 |

.243 |

.251 |

| Ruben Santana |

.192 |

.261 |

.288 |

.181 |

.248 |

.248 |

Pitchers – Standard

| Player |

T |

Age |

W |

L |

ERA |

G |

GS |

IP |

H |

ER |

HR |

BB |

SO |

| Corbin Burnes |

R |

31 |

11 |

6 |

3.19 |

25 |

25 |

155.0 |

132 |

55 |

15 |

48 |

144 |

| Zac Gallen |

R |

30 |

14 |

10 |

3.81 |

30 |

30 |

174.7 |

157 |

74 |

22 |

57 |

161 |

| Merrill Kelly |

R |

37 |

10 |

7 |

3.75 |

27 |

27 |

153.7 |

145 |

64 |

21 |

45 |

133 |

| Brandon Pfaadt |

R |

27 |

10 |

9 |

4.12 |

29 |

29 |

159.3 |

160 |

73 |

21 |

35 |

145 |

| Ryne Nelson |

R |

28 |

7 |

5 |

3.88 |

29 |

23 |

139.3 |

132 |

60 |

18 |

38 |

114 |

| Mitch Bratt |

L |

22 |

6 |

5 |

3.88 |

23 |

22 |

113.7 |

113 |

49 |

15 |

27 |

99 |

| Cristian Mena |

R |

23 |

4 |

4 |

3.83 |

19 |

16 |

89.3 |

83 |

38 |

11 |

32 |

85 |

| Eduardo Rodriguez |

L |

33 |

8 |

8 |

4.15 |

24 |

24 |

130.0 |

131 |

60 |

18 |

46 |

117 |

| Daniel Eagen |

R |

23 |

8 |

7 |

4.00 |

23 |

23 |

107.0 |

102 |

49 |

14 |

46 |

94 |

| Spencer Giesting |

L |

24 |

8 |

8 |

4.43 |

24 |

24 |

126.0 |

126 |

62 |

16 |

52 |

102 |

| Drey Jameson |

R |

28 |

6 |

4 |

3.93 |

20 |

12 |

75.7 |

73 |

33 |

8 |

29 |

66 |

| Michael Soroka |

R |

28 |

6 |

6 |

4.12 |

24 |

16 |

91.7 |

79 |

42 |

11 |

35 |

90 |

| A.J. Puk |

L |

31 |

6 |

3 |

3.19 |

55 |

2 |

59.3 |

49 |

21 |

7 |

19 |

74 |

| Dylan Ray |

R |

25 |

7 |

8 |

4.50 |

24 |

24 |

116.0 |

119 |

58 |

15 |

41 |

87 |

| Kohl Drake |

L |

25 |

6 |

6 |

4.19 |

19 |

17 |

81.7 |

80 |

38 |

11 |

30 |

76 |

| Nabil Crismatt |

R |

31 |

5 |

6 |

4.31 |

26 |

18 |

102.3 |

111 |

49 |

14 |

26 |

65 |

| Yilber Díaz |

R |

25 |

5 |

4 |

4.16 |

30 |

15 |

84.3 |

78 |

39 |

10 |

42 |

81 |

| Andrew Hoffmann |

R |

26 |

6 |

5 |

4.06 |

34 |

11 |

77.7 |

77 |

35 |

10 |

30 |

70 |

| Yu-Min Lin |

L |

22 |

5 |

6 |

4.50 |

23 |

23 |

104.0 |

108 |

52 |

12 |

44 |

77 |

| Tommy Henry |

L |

28 |

5 |

6 |

4.55 |

20 |

18 |

99.0 |

102 |

50 |

13 |

37 |

74 |

| Justin Martinez |

R |

24 |

5 |

3 |

3.34 |

52 |

0 |

59.3 |

45 |

22 |

4 |

33 |

74 |

| Billy Corcoran |

R |

26 |

5 |

6 |

4.46 |

16 |

16 |

80.7 |

88 |

40 |

11 |

24 |

53 |

| Taylor Rashi |

R |

30 |

4 |

2 |

3.78 |

43 |

2 |

69.0 |

64 |

29 |

7 |

30 |

68 |

| Jalen Beeks |

L |

32 |

5 |

3 |

3.71 |

52 |

3 |

60.7 |

58 |

25 |

6 |

24 |

52 |

| Jose Cabrera |

R |

24 |

6 |

7 |

4.82 |

23 |

22 |

112.0 |

119 |

60 |

16 |

44 |

76 |

| Blake Walston |

L |

25 |

4 |

5 |

4.59 |

18 |

16 |

84.3 |

87 |

43 |

10 |

38 |

60 |

| Avery Short |

L |

25 |

5 |

6 |

4.78 |

20 |

19 |

92.3 |

101 |

49 |

13 |

34 |

56 |

| Kevin Ginkel |

R |

32 |

4 |

3 |

3.42 |

49 |

0 |

47.3 |

41 |

18 |

4 |

19 |

49 |

| Ryan Thompson |

R |

34 |

4 |

2 |

3.55 |

49 |

0 |

45.7 |

44 |

18 |

5 |

13 |

37 |

| Bryce Jarvis |

R |

28 |

4 |

5 |

4.65 |

29 |

16 |

93.0 |

92 |

48 |

12 |

43 |

73 |

| Anthony DeSclafani |

R |

36 |

3 |

3 |

4.53 |

15 |

10 |

57.7 |

62 |

29 |

9 |

19 |

46 |

| Andrew Saalfrank |

L |

28 |

4 |

2 |

3.72 |

40 |

0 |

46.0 |

42 |

19 |

4 |

24 |

41 |

| Brandyn Garcia |

L |

26 |

5 |

5 |

4.39 |

38 |

8 |

69.7 |

68 |

34 |

8 |

31 |

59 |

| Roman Angelo |

R |

26 |

5 |

7 |

4.94 |

23 |

23 |

109.3 |

112 |

60 |

15 |

55 |

85 |

| Sean Reid-Foley |

R |

30 |

3 |

2 |

3.69 |

39 |

0 |

39.0 |

34 |

16 |

3 |

22 |

41 |

| Jonatan Bernal |

R |

24 |

4 |

4 |

4.66 |

19 |

9 |

65.7 |

75 |

34 |

9 |

20 |

36 |

| Alec Baker |

R |

26 |

3 |

3 |

4.76 |

26 |

11 |

75.7 |

84 |

40 |

11 |

26 |

47 |

| Kyle Backhus |

L |

28 |

5 |

4 |

3.78 |

50 |

0 |

50.0 |

46 |

21 |

5 |

20 |

49 |

| Gus Varland |

R |

29 |

3 |

2 |

4.03 |

42 |

2 |

51.3 |

50 |

23 |

5 |

24 |

50 |

| Kyle Amendt |

R |

26 |

2 |

1 |

3.86 |

35 |

0 |

37.3 |

32 |

16 |

4 |

21 |

41 |

| Philip Abner |

L |

24 |

2 |

3 |

4.05 |

52 |

0 |

53.3 |

51 |

24 |

6 |

21 |

50 |

| Junior Fernández |

R |

29 |

4 |

3 |

3.95 |

37 |

0 |

43.3 |

42 |

19 |

5 |

21 |

41 |

| Luke Albright |

R |

26 |

3 |

4 |

4.81 |

20 |

10 |

63.7 |

64 |

34 |

8 |

37 |

53 |

| Trevor Richards |

R |

33 |

2 |

1 |

4.27 |

42 |

2 |

52.7 |

51 |

25 |

7 |

23 |

51 |

| Anthony Gose |

L |

35 |

3 |

3 |

4.00 |

34 |

0 |

36.0 |

34 |

16 |

5 |

17 |

39 |

| Kendall Graveman |

R |

35 |

2 |

2 |

4.33 |

37 |

1 |

35.3 |

35 |

17 |

4 |

18 |

32 |

| Matt Foster |

R |

31 |

2 |

1 |

4.01 |

31 |

0 |

33.7 |

33 |

15 |

5 |

11 |

31 |

| Casey Anderson |

R |

25 |

6 |

8 |

5.07 |

24 |

13 |

81.7 |

87 |

46 |

11 |

38 |

56 |

| Christian Montes De Oca |

R |

26 |

3 |

2 |

4.20 |

34 |

0 |

45.0 |

45 |

21 |

5 |

15 |

35 |

| Jeff Brigham |

R |

34 |

3 |

3 |

4.36 |

29 |

1 |

33.0 |

30 |

16 |

5 |

16 |

35 |

| John Curtiss |

R |

33 |

3 |

3 |

4.30 |

44 |

1 |

52.3 |

54 |

25 |

8 |

15 |

41 |

| Juan Morillo |

R |

27 |

3 |

2 |

4.18 |

52 |

0 |

47.3 |

46 |

22 |

5 |

27 |

45 |

| Gerardo Carrillo |

R |

27 |

2 |

3 |

4.22 |

38 |

0 |

42.7 |

41 |

20 |

5 |

18 |

38 |

| Sean Harney |

R |

27 |

1 |

1 |

4.78 |

23 |

4 |

37.7 |

40 |

20 |

5 |

17 |

26 |

| Elvin Rodriguez |

R |

28 |

3 |

3 |

5.00 |

26 |

8 |

63.0 |

70 |

35 |

11 |

20 |

45 |

| Isaiah Campbell |

R |

28 |

6 |

5 |

4.34 |

42 |

0 |

56.0 |

60 |

27 |

7 |

18 |

38 |

| Casey Kelly |

R |

36 |

4 |

6 |

5.23 |

21 |

18 |

103.3 |

125 |

60 |

17 |

37 |

53 |

| Juan Burgos |

R |

26 |

3 |

2 |

4.63 |

37 |

1 |

44.7 |

45 |

23 |

6 |

21 |

35 |

| Ryan Hendrix |

R |

31 |

4 |

3 |

4.31 |

33 |

0 |

39.7 |

37 |

19 |

4 |

21 |

37 |

| Antonio Menendez |

R |

27 |

3 |

3 |

4.53 |

33 |

0 |

45.7 |

45 |

23 |

5 |

22 |

35 |

| Kyle Nelson |

L |

29 |

2 |

3 |

4.74 |

45 |

1 |

38.0 |

38 |

20 |

6 |

16 |

32 |

| Zane Russell |

R |

26 |

4 |

5 |

4.57 |

43 |

0 |

45.3 |

45 |

23 |

6 |

22 |

38 |

| Hayden Durke |

R |

24 |

3 |

3 |

4.53 |

44 |

0 |

45.7 |

40 |

23 |

5 |

31 |

44 |

| Logan Clayton |

R |

26 |

3 |

5 |

5.34 |

17 |

11 |

59.0 |

68 |

35 |

9 |

27 |

32 |

| Conor Grammes |

R |

28 |

1 |

2 |

4.84 |

30 |

1 |

35.3 |

34 |

19 |

4 |

24 |

33 |

| Alfred Morillo |

R |

24 |

2 |

3 |

4.67 |

41 |

0 |

52.0 |

51 |

27 |

6 |

28 |

42 |

| Gerardo Gutierrez |

R |

27 |

2 |

2 |

4.95 |

27 |

0 |

36.3 |

39 |

20 |

5 |

16 |

26 |

| Landon Sims |

R |

25 |

2 |

3 |

4.81 |

43 |

1 |

48.7 |

49 |

26 |

7 |

27 |

42 |

| Jake Rice |

L |

28 |

2 |

2 |

4.78 |

41 |

0 |

49.0 |

48 |

26 |

6 |

29 |

42 |

| Eli Saul |

R |

24 |

3 |

4 |

4.82 |

50 |

1 |

56.0 |

59 |

30 |

7 |

30 |

38 |

| Jhosmer Alvarez |

R |

25 |

2 |

4 |

5.02 |

27 |

0 |

37.7 |

39 |

21 |

5 |

21 |

26 |

| Zach Barnes |

R |

27 |

2 |

3 |

5.30 |

28 |

0 |

37.3 |

41 |

22 |

5 |

21 |

24 |

| Nate Savino |

L |

24 |

2 |

3 |

5.31 |

31 |

3 |

61.0 |

64 |

36 |

8 |

37 |

40 |

Pitchers – Advanced

| Player |

IP |

K/9 |

BB/9 |

HR/9 |

BB% |

K% |

BABIP |

ERA+ |

3ERA+ |

FIP |

ERA- |

WAR |

| Corbin Burnes |

155.0 |

8.4 |

2.8 |

0.9 |

7.5% |

22.5% |

.274 |

131 |

126 |

3.61 |

76 |

3.4 |

| Zac Gallen |

174.7 |

8.3 |

2.9 |

1.1 |

7.8% |

22.0% |

.278 |

110 |

108 |

4.04 |

91 |

2.7 |

| Merrill Kelly |

153.7 |

7.8 |

2.6 |

1.2 |

7.0% |

20.7% |

.281 |

112 |

103 |

4.13 |

90 |

2.5 |

| Brandon Pfaadt |

159.3 |

8.2 |

2.0 |

1.2 |

5.3% |

21.8% |

.302 |

101 |

101 |

3.87 |

99 |

1.9 |

| Ryne Nelson |

139.3 |

7.4 |

2.5 |

1.2 |

6.5% |

19.6% |

.279 |

108 |

107 |

4.11 |

93 |

1.9 |

| Mitch Bratt |

113.7 |

7.8 |

2.1 |

1.2 |

5.7% |

20.9% |

.295 |

108 |

113 |

3.96 |

93 |

1.8 |

| Cristian Mena |

89.3 |

8.6 |

3.2 |

1.1 |

8.4% |

22.3% |

.289 |

109 |

115 |

4.04 |

92 |

1.5 |

| Eduardo Rodriguez |

130.0 |

8.1 |

3.2 |

1.2 |

8.2% |

20.9% |

.300 |

101 |

96 |

4.27 |

99 |

1.5 |

| Daniel Eagen |

107.0 |

7.9 |

3.9 |

1.2 |

9.7% |

19.9% |

.287 |

102 |

107 |

4.43 |

98 |

1.3 |

| Spencer Giesting |

126.0 |

7.3 |

3.7 |

1.1 |

9.4% |

18.4% |

.292 |

94 |

100 |

4.67 |

106 |

1.2 |

| Drey Jameson |

75.7 |

7.9 |

3.4 |

1.0 |

8.9% |

20.2% |

.294 |

107 |

108 |

4.10 |

94 |

1.1 |

| Michael Soroka |

91.7 |

8.8 |

3.4 |

1.1 |

9.1% |

23.4% |

.275 |

101 |

103 |

4.20 |

99 |

1.1 |

| A.J. Puk |

59.3 |

11.2 |

2.9 |

1.1 |

7.8% |

30.2% |

.296 |

131 |

129 |

3.37 |

76 |

1.1 |

| Dylan Ray |

116.0 |

6.8 |

3.2 |

1.2 |

8.1% |

17.2% |

.292 |

93 |

97 |

4.56 |

108 |

1.0 |

| Kohl Drake |

81.7 |

8.4 |

3.3 |

1.2 |

8.5% |

21.4% |

.297 |

100 |

106 |

4.30 |

100 |

1.0 |

| Nabil Crismatt |

102.3 |

5.7 |

2.3 |

1.2 |

5.9% |

14.8% |

.293 |

97 |

95 |

4.52 |

103 |

1.0 |

| Yilber Díaz |

84.3 |

8.6 |

4.5 |

1.1 |

11.1% |

21.5% |

.291 |

101 |

107 |

4.42 |

99 |

0.9 |

| Andrew Hoffmann |

77.7 |

8.1 |

3.5 |

1.2 |

8.8% |

20.6% |

.298 |

103 |

106 |

4.31 |

97 |

0.9 |

| Yu-Min Lin |

104.0 |

6.7 |

3.8 |

1.0 |

9.6% |

16.7% |

.297 |

93 |

100 |

4.68 |

108 |

0.9 |

| Tommy Henry |

99.0 |

6.7 |

3.4 |

1.2 |

8.6% |

17.2% |

.293 |

92 |

94 |

4.62 |

109 |

0.8 |

| Justin Martinez |

59.3 |

11.2 |

5.0 |

0.6 |

12.8% |

28.8% |

.291 |

125 |

131 |

3.47 |

80 |

0.8 |

| Billy Corcoran |

80.7 |

5.9 |

2.7 |

1.2 |

6.8% |

15.0% |

.296 |

94 |

97 |

4.63 |

106 |

0.7 |

| Taylor Rashi |

69.0 |

8.9 |

3.9 |

0.9 |

10.0% |

22.7% |

.298 |

111 |

110 |

3.90 |

90 |

0.7 |

| Jalen Beeks |

60.7 |

7.7 |

3.6 |

0.9 |

9.1% |

19.8% |

.292 |

113 |

109 |

4.07 |

88 |

0.6 |

| Jose Cabrera |

112.0 |

6.1 |

3.5 |

1.3 |

8.8% |

15.2% |

.291 |

87 |

92 |

5.11 |

115 |

0.6 |

| Blake Walston |

84.3 |

6.4 |

4.1 |

1.1 |

10.2% |

16.0% |

.293 |

91 |

95 |

4.81 |

110 |

0.6 |

| Avery Short |

92.3 |

5.5 |

3.3 |

1.3 |

8.4% |

13.8% |

.292 |

88 |

92 |

5.08 |

114 |

0.5 |

| Kevin Ginkel |

47.3 |

9.3 |

3.6 |

0.8 |

9.5% |

24.4% |

.291 |

122 |

116 |

3.52 |

82 |

0.5 |

| Ryan Thompson |

45.7 |

7.3 |

2.6 |

1.0 |

6.8% |

19.3% |

.287 |

118 |

110 |

3.95 |

85 |

0.5 |

| Bryce Jarvis |

93.0 |

7.1 |

4.2 |

1.2 |

10.4% |

17.7% |

.287 |

90 |

92 |

4.85 |

111 |

0.5 |

| Anthony DeSclafani |

57.7 |

7.2 |

3.0 |

1.4 |

7.6% |

18.3% |

.301 |

92 |

85 |

4.74 |

108 |

0.5 |

| Andrew Saalfrank |

46.0 |

8.0 |

4.7 |

0.8 |

11.7% |

20.0% |

.288 |

113 |

113 |

4.14 |

88 |

0.4 |

| Brandyn Garcia |

69.7 |

7.6 |

4.0 |

1.0 |

10.1% |

19.2% |

.293 |

95 |

98 |

4.73 |

105 |

0.4 |

| Roman Angelo |

109.3 |

7.0 |

4.5 |

1.2 |

11.1% |

17.1% |

.292 |

85 |

88 |

5.20 |

118 |

0.4 |

| Sean Reid-Foley |

39.0 |

9.5 |

5.1 |

0.7 |

12.6% |

23.6% |

.298 |

113 |

113 |

3.83 |

88 |

0.3 |

| Jonatan Bernal |

65.7 |

4.9 |

2.7 |

1.2 |

6.9% |

12.4% |

.297 |

90 |

95 |

4.90 |

111 |

0.3 |

| Alec Baker |

75.7 |

5.6 |

3.1 |

1.3 |

7.8% |

14.1% |

.296 |

88 |

91 |

5.00 |

114 |

0.3 |

| Kyle Backhus |

50.0 |

8.8 |

3.6 |

0.9 |

9.3% |

22.8% |

.295 |

111 |

110 |

4.00 |

90 |

0.3 |

| Gus Varland |

51.3 |

8.8 |

4.2 |

0.9 |

10.5% |

21.9% |

.310 |

104 |

102 |

4.12 |

96 |

0.3 |

| Kyle Amendt |

37.3 |

9.9 |

5.1 |

1.0 |

12.7% |

24.7% |

.289 |

108 |

114 |

4.05 |

92 |

0.3 |

| Philip Abner |

53.3 |

8.4 |

3.5 |

1.0 |

9.2% |

21.9% |

.298 |

103 |

110 |

4.10 |

97 |

0.2 |

| Junior Fernández |

43.3 |

8.5 |

4.4 |

1.0 |

10.7% |

20.9% |

.301 |

106 |

105 |

4.43 |

94 |

0.2 |

| Luke Albright |

63.7 |

7.5 |

5.2 |

1.1 |

12.6% |

18.0% |

.296 |

87 |

90 |

5.06 |

115 |

0.2 |

| Trevor Richards |

52.7 |

8.7 |

3.9 |

1.2 |

9.8% |

21.7% |

.299 |

98 |

94 |

4.32 |

102 |

0.2 |

| Anthony Gose |

36.0 |

9.8 |

4.3 |

1.3 |

10.6% |

24.4% |

.302 |

105 |

95 |

4.30 |

96 |

0.1 |

| Kendall Graveman |

35.3 |

8.2 |

4.6 |

1.0 |

11.4% |

20.3% |

.304 |

97 |

91 |

4.52 |

103 |

0.1 |

| Matt Foster |

33.7 |

8.3 |

2.9 |

1.3 |

7.6% |

21.5% |

.292 |

104 |

101 |

4.32 |

96 |

0.1 |

| Casey Anderson |

81.7 |

6.2 |

4.2 |

1.2 |

10.3% |

15.1% |

.293 |

83 |

87 |

5.34 |

120 |

0.1 |

| Christian Montes De Oca |

45.0 |

7.0 |

3.0 |

1.0 |

7.6% |

17.8% |

.292 |

100 |

103 |

4.25 |

100 |

0.1 |

| Jeff Brigham |

33.0 |

9.5 |

4.4 |

1.4 |

11.1% |

24.3% |

.287 |

96 |

91 |

4.65 |

104 |

0.1 |

| John Curtiss |

52.3 |

7.1 |

2.6 |

1.4 |

6.7% |

18.4% |

.291 |

97 |

95 |

4.50 |

103 |

0.1 |

| Juan Morillo |

47.3 |

8.6 |

5.1 |

1.0 |

12.4% |

20.6% |

.304 |

100 |

101 |

4.47 |

100 |

0.1 |

| Gerardo Carrillo |

42.7 |

8.0 |

3.8 |

1.1 |

9.5% |

20.1% |

.293 |

99 |

102 |

4.59 |

101 |

0.1 |

| Sean Harney |

37.7 |

6.2 |

4.1 |

1.2 |

10.1% |

15.5% |

.294 |

88 |

90 |

5.10 |

114 |

0.0 |

| Elvin Rodriguez |

63.0 |

6.4 |

2.9 |

1.6 |

7.2% |

16.3% |

.298 |

84 |

86 |

5.05 |

119 |

0.0 |

| Isaiah Campbell |

56.0 |

6.1 |

2.9 |

1.1 |

7.3% |

15.4% |

.296 |

96 |

98 |

4.56 |

104 |

0.0 |

| Casey Kelly |

103.3 |

4.6 |

3.2 |

1.5 |

7.9% |

11.3% |

.303 |

80 |

75 |

5.52 |

125 |

0.0 |

| Juan Burgos |

44.7 |

7.0 |

4.2 |

1.2 |

10.6% |

17.6% |

.289 |

90 |

94 |

5.02 |

111 |

0.0 |

| Ryan Hendrix |

39.7 |

8.4 |

4.8 |

0.9 |

11.9% |

20.9% |

.295 |

97 |

93 |

4.65 |

103 |

0.0 |

| Antonio Menendez |

45.7 |

6.9 |

4.3 |

1.0 |

10.7% |

17.1% |

.288 |

92 |

95 |

4.83 |

108 |

0.0 |

| Kyle Nelson |

38.0 |

7.6 |

3.8 |

1.4 |

9.6% |

19.3% |

.288 |

88 |

91 |

4.87 |

114 |

-0.1 |

| Zane Russell |

45.3 |

7.5 |

4.4 |

1.2 |

10.8% |

18.7% |

.291 |

92 |

97 |

4.66 |

109 |

-0.1 |

| Hayden Durke |

45.7 |

8.7 |

6.1 |

1.0 |

14.7% |

20.9% |

.280 |

92 |

98 |

5.02 |

108 |

-0.1 |

| Logan Clayton |

59.0 |

4.9 |

4.1 |

1.4 |

9.9% |

11.7% |

.296 |

78 |

81 |

5.64 |

128 |

-0.1 |

| Conor Grammes |

35.3 |

8.4 |

6.1 |

1.0 |

14.3% |

19.6% |

.297 |

86 |

87 |

5.31 |

116 |

-0.2 |

| Alfred Morillo |

52.0 |

7.3 |

4.8 |

1.0 |

11.9% |

17.9% |

.290 |

90 |

94 |

5.01 |

111 |

-0.2 |

| Gerardo Gutierrez |

36.3 |

6.4 |

4.0 |

1.2 |

9.7% |

15.8% |

.298 |

84 |

87 |

5.09 |

119 |

-0.2 |

| Landon Sims |

48.7 |

7.8 |

5.0 |

1.3 |

12.2% |

18.9% |

.294 |

87 |

92 |

5.16 |

115 |

-0.2 |

| Jake Rice |

49.0 |

7.7 |

5.3 |

1.1 |

12.9% |

18.8% |

.294 |

88 |

89 |

5.12 |

114 |

-0.2 |

| Eli Saul |

56.0 |

6.1 |

4.8 |

1.1 |

11.5% |

14.5% |

.292 |

87 |

92 |

5.41 |

115 |

-0.3 |

| Jhosmer Alvarez |

37.7 |

6.2 |

5.0 |

1.2 |

12.0% |

14.9% |

.288 |

83 |

88 |

5.42 |

120 |

-0.3 |

| Zach Barnes |

37.3 |

5.8 |

5.1 |

1.2 |

11.9% |

13.6% |

.298 |

79 |

82 |

5.63 |

127 |

-0.4 |

| Nate Savino |

61.0 |

5.9 |

5.5 |

1.2 |

13.1% |

14.2% |

.289 |

79 |

84 |

5.72 |

127 |

-0.4 |

Pitchers – Top Near-Age Comps

Pitchers – Splits and Percentiles

| Player |

BA vs. L |

OBP vs. L |

SLG vs. L |

BA vs. R |

OBP vs. R |

SLG vs. R |

80th WAR |

20th WAR |

80th ERA |

20th ERA |

| Corbin Burnes |

.234 |

.303 |

.357 |

.221 |

.280 |

.354 |

4.2 |

2.4 |

2.77 |

3.70 |

| Zac Gallen |

.234 |

.299 |

.375 |

.240 |

.303 |

.408 |

3.7 |

1.4 |

3.35 |

4.46 |

| Merrill Kelly |

.245 |

.309 |

.415 |

.247 |

.290 |

.409 |

3.4 |

1.4 |

3.17 |

4.42 |

| Brandon Pfaadt |

.274 |

.325 |

.439 |

.235 |

.274 |

.390 |

3.1 |

0.8 |

3.52 |

4.73 |

| Ryne Nelson |

.239 |

.292 |

.388 |

.252 |

.304 |

.422 |

2.8 |

1.2 |

3.39 |

4.36 |

| Mitch Bratt |

.241 |

.292 |

.368 |

.255 |

.298 |

.425 |

2.8 |

1.1 |

3.12 |

4.49 |

| Cristian Mena |

.255 |

.322 |

.430 |

.225 |

.292 |

.357 |

2.1 |

0.8 |

3.22 |

4.53 |

| Eduardo Rodriguez |

.263 |

.320 |

.430 |

.253 |

.316 |

.421 |

2.4 |

0.4 |

3.56 |

5.00 |

| Daniel Eagen |

.251 |

.333 |

.425 |

.237 |

.303 |

.379 |

2.0 |

0.7 |

3.65 |

4.58 |

| Spencer Giesting |

.235 |

.327 |

.353 |

.261 |

.337 |

.439 |

2.0 |

0.5 |

3.95 |

4.87 |

| Drey Jameson |

.272 |

.351 |

.434 |

.226 |

.295 |

.346 |

1.6 |

0.6 |

3.41 |

4.51 |

| Michael Soroka |

.238 |

.326 |

.409 |

.221 |

.302 |

.359 |

1.6 |

0.4 |

3.62 |

4.81 |

| A.J. Puk |

.192 |

.263 |

.301 |

.233 |

.305 |

.393 |

1.8 |

0.3 |

2.43 |

4.35 |

| Dylan Ray |

.252 |

.323 |

.419 |

.264 |

.326 |

.416 |

1.7 |

0.3 |

4.02 |

5.04 |

| Kohl Drake |

.263 |

.327 |

.384 |

.242 |

.315 |

.426 |

1.6 |

0.3 |

3.69 |

4.95 |

| Nabil Crismatt |

.258 |

.314 |

.427 |

.280 |

.319 |

.444 |

1.5 |

0.4 |

3.88 |

4.78 |

| Yilber Díaz |

.234 |

.333 |

.386 |

.242 |

.329 |

.396 |

1.6 |

0.3 |

3.61 |

4.79 |

| Andrew Hoffmann |

.266 |

.346 |

.441 |

.238 |

.300 |

.384 |

1.4 |

0.2 |

3.49 |

4.76 |

| Yu-Min Lin |

.248 |

.326 |

.368 |

.263 |

.344 |

.423 |

1.5 |

0.3 |

4.08 |

5.03 |

| Tommy Henry |

.248 |

.322 |

.400 |

.264 |

.329 |

.431 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

4.08 |

5.27 |

| Justin Martinez |

.210 |

.336 |

.310 |

.198 |

.305 |

.306 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

2.77 |

4.33 |

| Billy Corcoran |

.270 |

.338 |

.418 |

.267 |

.308 |

.449 |

1.1 |

0.2 |

4.03 |

5.01 |

| Taylor Rashi |

.235 |

.313 |

.387 |

.242 |

.321 |

.362 |

1.1 |

0.0 |

3.24 |

4.75 |

| Jalen Beeks |

.219 |

.293 |

.329 |

.259 |

.335 |

.401 |

1.1 |

0.1 |

3.08 |

4.46 |

| Jose Cabrera |

.276 |

.357 |

.467 |

.258 |

.330 |

.416 |

1.1 |

-0.1 |

4.39 |

5.31 |

| Blake Walston |

.253 |

.355 |

.396 |

.263 |

.337 |

.424 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

4.18 |

5.12 |

| Avery Short |

.250 |

.331 |

.375 |

.280 |

.343 |

.470 |

0.9 |

0.0 |

4.39 |

5.26 |

| Kevin Ginkel |

.221 |

.310 |

.364 |

.235 |

.307 |

.343 |

0.9 |

-0.1 |

2.78 |

4.44 |

| Ryan Thompson |

.254 |

.315 |

.373 |

.248 |

.303 |

.413 |

0.8 |

0.0 |

2.94 |

4.43 |