Yu Darvish’s calling card has always been his dizzying array of pitches. Hard cutter, slow cutter, curve, knuckle curve, slow curve, shuuto — if you can name it, he can probably throw it in a major league game. That’s not an obviously great skill, in the same way as Gerrit Cole’s overpowering fastball or Jacob deGrom’s ability to throw sliders in the mid 90’s with command, but the results speak for themselves: Darvish has the third-highest career strikeout rate of any starter, active or otherwise, and impressive run prevention numbers to boot: his career ERA- and FIP- both check in at a sterling 82.

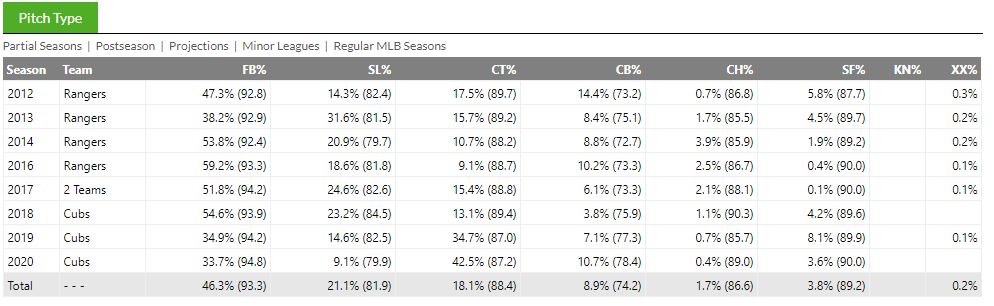

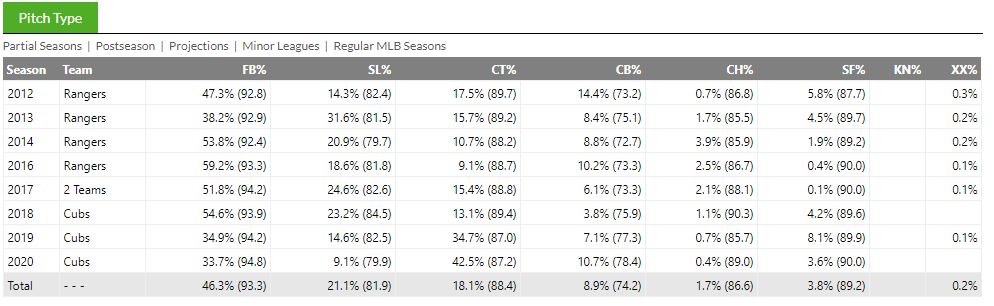

So okay, fine, Yu Darvish has two calling cards: tons of pitches and the ability to use those pitches effectively. Let’s talk about the tons of pitches today, though, because they’re way more fun. Consider, if you will, the two systems we use to classify pitches. Darvish’s career looks like a bingo board on both, but they’re two very different bingo boards. First, our standard pitch types:

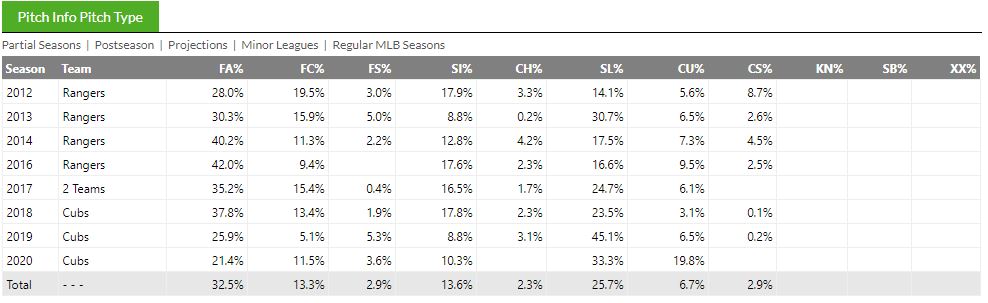

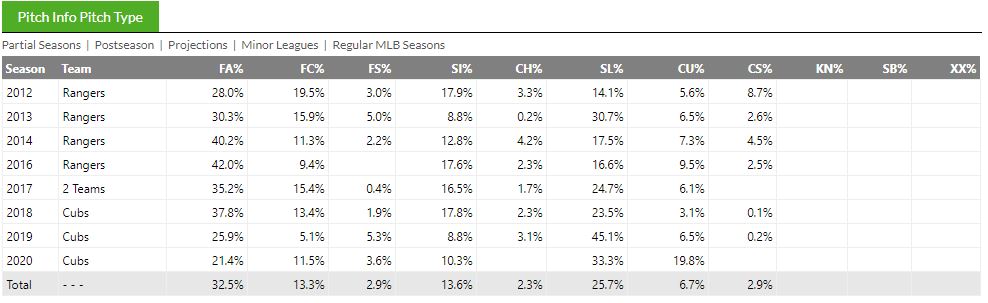

It’s a little bit of everything, with a heavy emphasis on cutters in the last two years. Meanwhile, the sliders have gotten slow — a near-career-low 79.9 mph, nearly as slow as his curveball, which has gotten fast. It’s a confusing mess. Next, take a look at pitch types per Pitch Info:

Rafts of sliders! More curveballs! The only thing the two systems seem to agree on is the 3.6% splitters, thrown at a dizzying 90 mph. You can’t see Pitch Info’s velocity numbers on here, but they’re divergent as well: these cutters are blazing, checking in at 92.3 mph, and the sliders are much faster than the first classification set, checking in at 86 mph.

What’s happening here is that the two systems don’t know what to do with Darvish’s array of breaking balls. Say, for the sake of argument, that Darvish throws seven different breaking balls, each with a different velocity and movement profile. Try to classify those using three buckets: cutter, slider, and curveball. Good luck! Here’s a pitch that Baseball Info Solutions, which doubles as our generic “Pitch Types” data source, classified as a cutter last night:

Looks like a cutter to me, or maybe a four-seamer that he over-cut inadvertently. It has a hair of glove-side break, which moves it from where O’Hearn thinks he’s swinging — middle-in fastball, a juicy first pitch target — to where he’s actually swinging, directly over the inside corner. At 93 mph, that’s a nasty pitch, no doubt, and it’s also pretty clearly a cut fastball. Darvish, who throws his four-seam fastball in the 95-96 mph range, is hardly throwing a 93 mph slider.

That was a gimme. How about this one?

Victor Caratini’s overzealous framing aside, that looks like a pretty different pitch to me. It’s slower, and bendier; if the last pitch had a hair of break, this one has an entire bearskin rug. It doesn’t have that cutter-esque ride, either. Just one problem: Darvish, by his own admission, throws two types of cutters. So maybe that’s a cutter too.

And what about this one?

Aside from Caratini’s framing paying off, that looks like a completely different pitch. It has as much vertical break as horizontal, and it’s 10 mph slower than the first cutter we looked at. Maybe this one’s a slider, then.

But what about this one, literally the previous pitch?

That’s even slower, but it has less drop; that looks more like a textbook slider, mostly glove-side break, though not a ton of break at that. East-West movement in the low 80s? Sounds like a slider to me. Before you go calling that a slider, though, consider this pitch, which was classified as a slider:

Gravity took this one far more than the last one, despite almost identical velocity. How can those two be the same pitch? And don’t go calling it a curve, either, because I’ve got one of those to show you, and it’s more North-South despite similar velocity:

And of course, Darvish throws two different types of curves — three, really, though we haven’t seen the extremely slow curve/eephus yet this year. Take a look at this majestic lollipop:

I just showed you seven different pitches. None of them were obviously the same if you look at the three critical elements of a pitch: velocity, vertical break, and horizontal break. Try fitting them into three buckets — cutter, slider, and curve — and you start to see the problems inherent in classifying Darvish’s pitches.

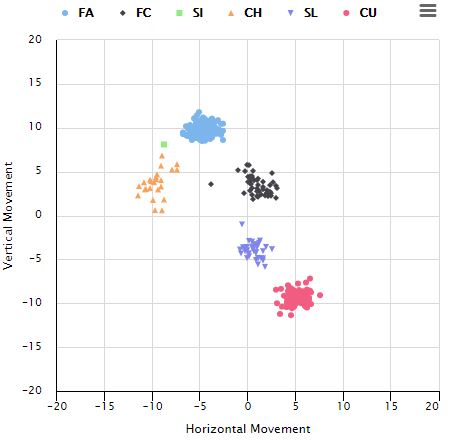

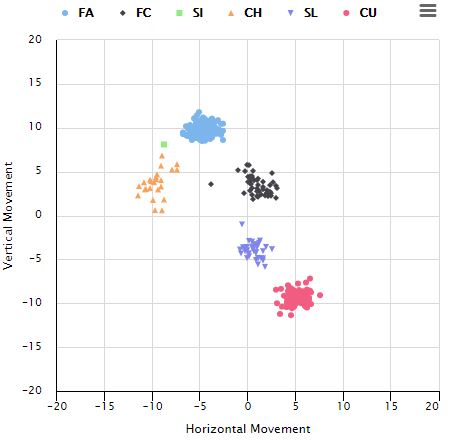

Still, even if you don’t have the right names for things, there’s often some internal logic. Take Shane Bieber’s new arsenal, for example. He calls his pitches a cutter, slider, and curve. I looked at them and saw two curves and a slider. We’ve since reclassified the “hard slider” to a cutter and the “hard curve” to a slider, which gives you this graph for all of his pitches in 2020:

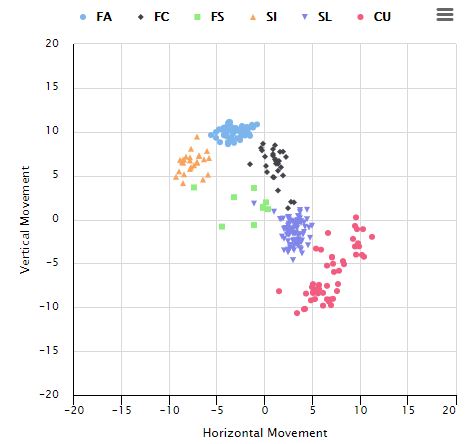

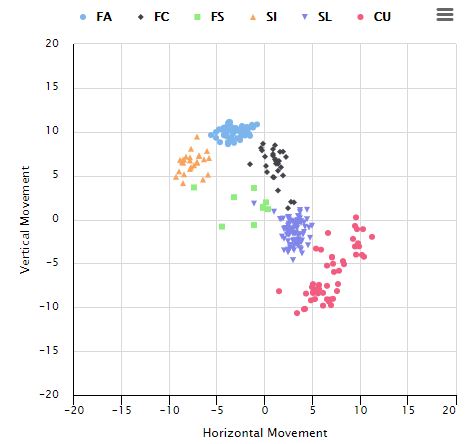

If you ignore the colors and shapes, there are five distinct spots. Quibble all day about what to call them — and we here at FanGraphs love to quibble, don’t get me wrong — but Bieber does five distinct things to the ball when he throws it, and that moves it into five distinct areas. Here’s Darvish’s 2020 chart:

This uses the Pitch Info classifications from above, which is why there are more “sliders” than “cutters,” but c’mon. These dots overlap. The edges bleed together, and there’s less center of mass. Some of the splitters are in the sinker quadrant, some in the slider quadrant. The cutters are everywhere, with some rising and some falling. The curveballs could easily be two pitches, and some could be sliders. Some of the curveballs have vertical movement if you don’t account for gravity!

When I set out to write this article, I wanted to talk about how Darvish was willing to throw any pitch in any count. The league as a whole decreases its fastball usage (excluding cutters) by five percentage points on two-strike counts. Darvish has thrown his more often with two strikes this year, 32.3% against 31% in all other counts. Take 0-0 out of the equation, and it’s even stranger: Darvish throws 43% fastballs to start an at-bat, then 24.5% fastballs until he hits two strikes, then 32.3% fastballs.

As I mulled over what to call each pitch and where to draw bright lines in describing his pitch usage, however, I changed my mind. Darvish isn’t exactly going against the grain, using his curveball when others would use their fastball and his slider when others would use their changeup. He changes each of his pitches so much, more run here or drop there, that while he does sometimes pitch against the grain, he sometimes throws a slider in a slider count and is still bucking convention, easier to do when you have fifteen sliders or whatever.

So in the end, forget all that noise. This isn’t an article about why Yu Darvish is great, at least not one of those nuts-and-bolts analytical articles where I show you the new pitch, show you how he’s using it in an interesting way, and then show you how that reduces hitters to a quivering mess in the batter’s box while unlocking fame and fortune for the pitcher.

This is an article about how fun it is to watch Darvish pitch and try to name the pitch he’s throwing. It’s wild. When he’s on, he can command them all at will — and as his 3.1% walk rate will tell you, he’s on right now. This form of Darvish is both dominant and delightful. Through three starts, he has a 2.12 ERA and a 1.63 FIP (2.99 xFIP). He has the second-most WAR among all pitchers this year, behind only Bieber. And yet, that’s not the fun part. The fun part is when he does this:

Which is a nasty enough pitch on its own, 97 on the black with some arm-side run to paint the corner, even if he missed Caratini’s target. But it’s not just that; it’s that in the same outing, he’s liable to do this:

And batters are so geared up for so many things that they just sometimes let it go by. Anyone can throw a 90 mph cutter that backs up and spins instead of breaking. When Darvish does it, though, you think hey, wait, maybe that was on purpose. Baseball is fun when you can analyze it, but it’s also fun when you’re left wondering, and no pitcher in baseball leaves me gleefully wondering more than Darvish right now.