We Are the Jonas Brothers and We Are Just as Confused as You Are

Dear baseball fans and Jonas Brothers fans,

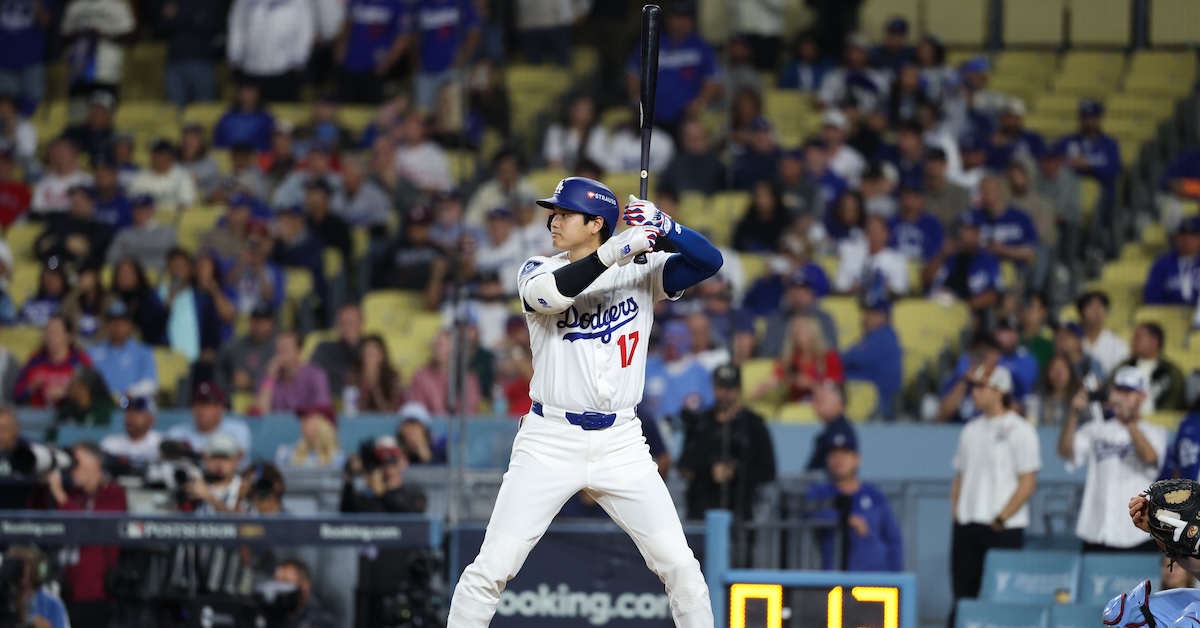

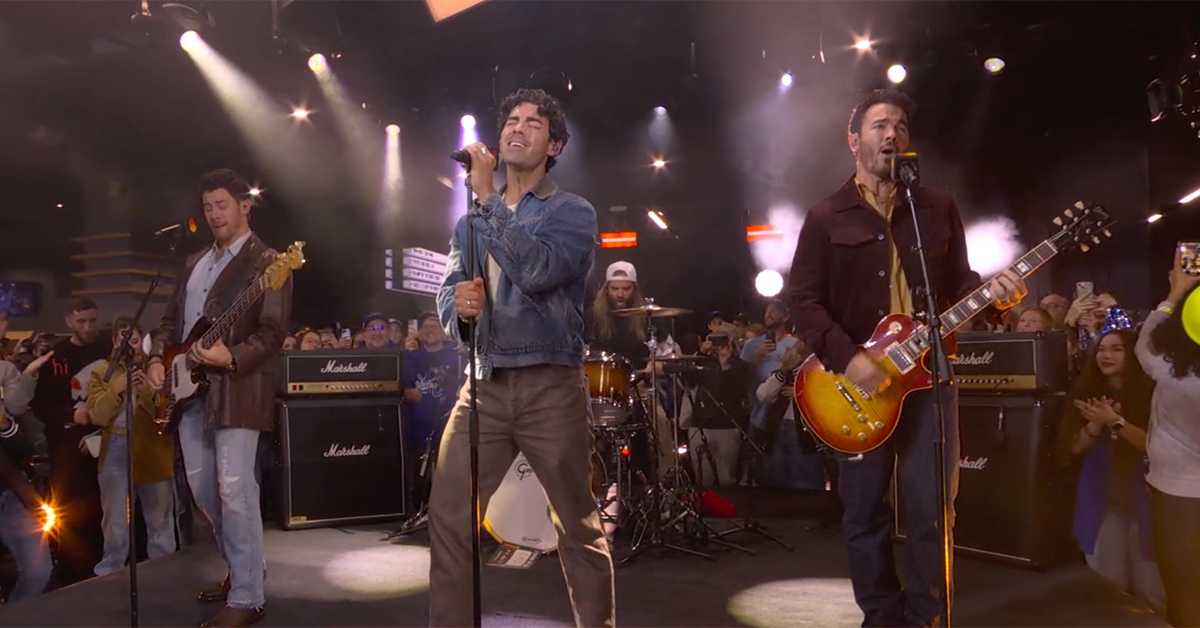

It has come to our attention that not all of you loved our performance during Game 2 of the World Series. This hurt us deeply, as we truly love to be loved. It has also come to our attention that some of you even blame us for the fact that the Dodgers ended up winning the game, and, well, we can’t really help you with that one. Even after much reflection and soul-searching, it’s still unclear how it could be our fault that Will Smith hit a home run 19 minutes and more than a full inning after we stopped playing. Nevertheless, all of us here at Jonas Brothers, Inc. want to make it very clear that we hear you. It had not occurred to us until our prerecorded backing track kicked in that maybe it was weird to interrupt the most important baseball game of the year for a performance that had nothing to do with baseball and little to do with anything. But we get it now. We promise to do better in the future, and we would like to explain how we found ourselves in this situation.

It’s important to understand that this is kind of a big production. We do a lot of shows. We’ve played at Rogers Centre four times now, which puts us just one behind Trey Yesavage. All those big shows require a lot of logistics. We have managers. We have handlers. We have managers for our handlers. (We call them manhandlers. It is our favorite joke.) Once you’ve gotten to the point where you’re singing into a microphone with a giant MasterCard logo on it, you’re not necessarily the one making all the decisions. The point is, we stopped asking questions a long time ago. We’ve performed at the White House Easter Egg Roll. That constituted a normal day in the life of the Jonas Brothers. Read the rest of this entry »