The Twins Search for Gold on the Waiver Wire

While championship retrospectives are still being read and written, the rest of baseball is gearing up for the offseason. Immediately following the World Series, there’s always a flurry of activity as players come off the 60-day injured list, and teams get their 40-man rosters in order and begin the long process of building for next season. During these initial days of the offseason, the waiver wire is flooded with players who were removed from their team’s roster. With so many players shuffling around, these minor moves can get swept under the rug pretty quickly. After all, it’s unlikely a waiver claim in November will have much of an effect on a team’s fortunes next season. But sometimes the waiver wire holds a piece of true gold amidst all the pyrite.

Last year, the Rays claimed Oliver Drake from the Twins on November 1. It was the fourth time Drake had been claimed off waivers, with the Twins his seventh team in 2018. He was later designated for assignment three times that offseason, claimed by another team, and then traded back to the Rays in early January. That’s not exactly the ideal blueprint for how these waiver wire claims should go, but Drake’s performance during the 2019 season was as good as the Rays could have hoped for (3.87 FIP, 0.5 WAR).

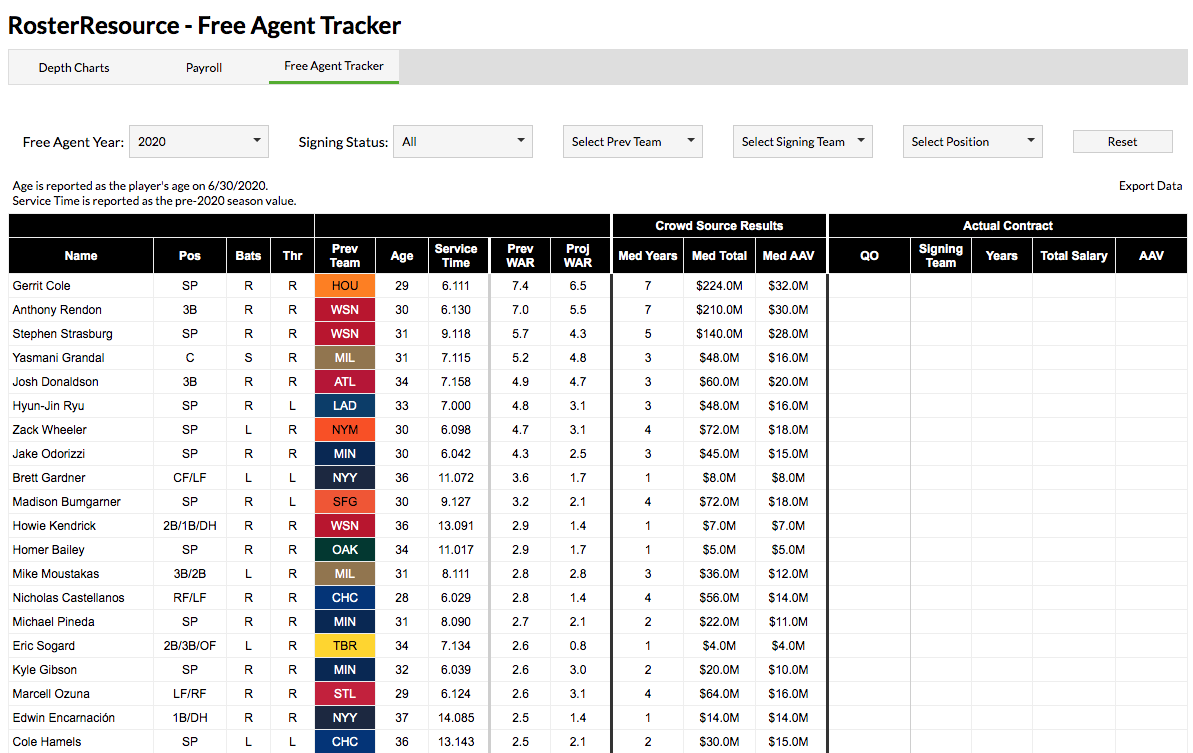

The Twins are hoping to uncover their own piece of treasure in Matt Wisler. Claimed off waivers from the Mariners, Wisler certainly looks the part of roster chaff. A former top prospect, he was included in the first big Craig Kimbrel trade before he could make his debut with his original team, the Padres. He struggled in the Braves rotation for a couple of years before getting moved to the bullpen in 2017, and has bounced around the league the last two seasons, from Atlanta to Cincinnati in 2018, then back to San Diego in 2019, and finally to Seattle. Since making the transition to relief work, he’s posted an ugly 5.89 ERA and a 4.63 FIP across 123.2 innings, accumulating 0.4 WAR in three seasons.

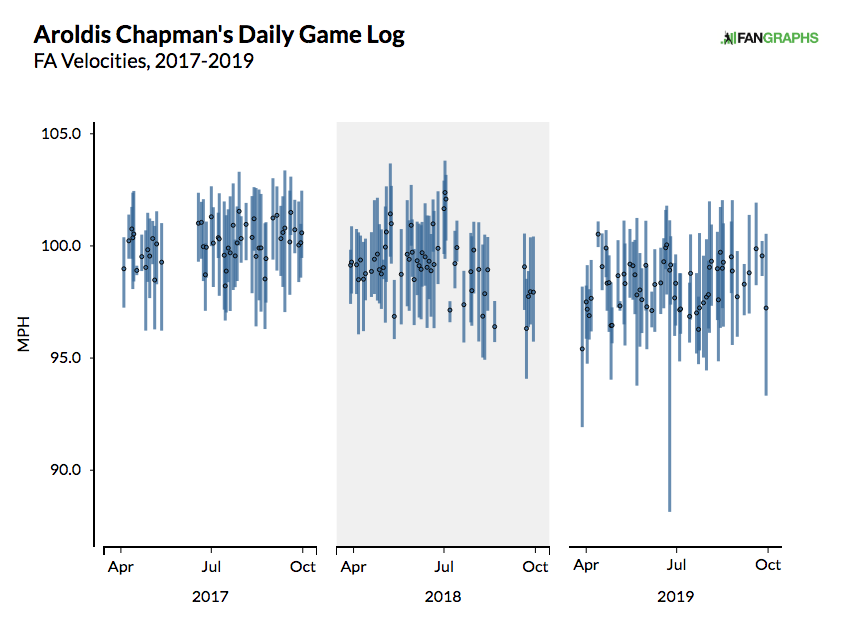

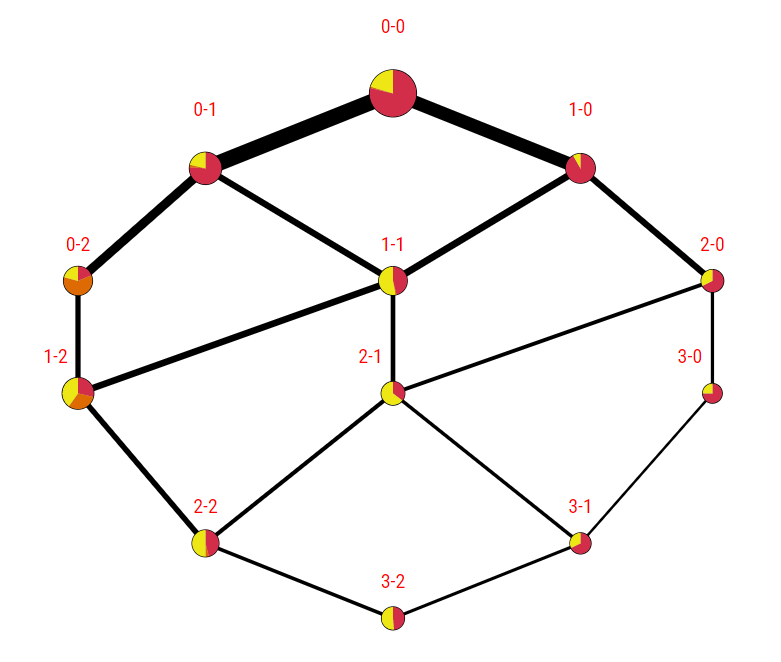

Besides his long-forgotten prospect pedigree, Wisler looks exactly like the kind of depth that gets shuffled around in November before getting buried on the depth chart once the offseason begins in earnest. But digging below the surface reveals the potential for gold. Since 2017, Wisler has increased his strikeout rate at each stop in the majors, from 14.4% with the Braves to 30.5% with the Mariners. His ability to prevent runs hasn’t benefited from all those extra strikeouts, but it gives him an intriguing foundation that could be honed with a little development. Read the rest of this entry »