Over the course of the last two painfully slow offseasons, baseball fans, agents, and writers have speculated about the possibility that collusion might be responsible. We aren’t going to talk about that today. Instead, we’re going to talk about the report from Marc Carig late last month about Major League Baseball awarding a prize for the team most successful in suppressing arbitration salaries.

The Belt changes hands shortly after season’s end, in a crowded conference room at a luxury resort, where delegates from every MLB team have been summoned for a symposium on arbitration. For three hours, they will work together at the direction of the league to set recommendations, which teams will use in negotiations with their players. It’s a thankless job. So before the meeting adjourns, they’ll celebrate an unsung hero in this battle over dollars. The ceremony ends with the presentation of a replica championship belt, awarded by the league to the team that did most to “achieve the goals set by the industry.” In other words: The team that did the most to keep salaries down in arbitration…

…In a statement, Major League Baseball acknowledged The Belt as “an informal recognition of those club’s salary arbitration departments that did the best.”

Now, this may seem like an insignificant token – after all, a plastic belt awarded as a trophy is in most contexts rather innocuous. But this is more complicated than it appears at first glance.

Collusion is a violation of the Collective Bargaining Agreement, as we discussed in February. The word “collusion” doesn’t appear in the Major League Rules, and it isn’t in the Collective Bargaining Agreement either. However, the Collective Bargaining Agreement does say in Article XX – governing the Reserve System – that rights under the CBA are individual, not collective.

The utilization or non-utilization of rights under Article XIX(A)(2) and Article XX is an individual matter to be determined solely by each Player and each Club for his or its own benefit. Players shall not act in concert with other Players and Clubs shall not act in concert with other Clubs.

Let’s refresh our recollections on what collusion is in the context of major league baseball, beginning with the preeminent legal definition of collusion from Darren Heitner and Jillian Postal, who wrote a particularly excellent note on the subject for Harvard Law School’s Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law.

Collusion at its core is collective action that restricts competition. Under federal law, particularly the Sherman Anti-Trust Act (the “Sherman Act”), collusion is prohibited; however, because of labor exemptions, what constitutes collusive, prohibited behavior in specific sports leagues varies based on the league’s negotiated collective bargaining agreement (“CBA”).

And, as Marc Edelman explained for Forbes:

Although collusion under Baseball’s collective bargaining agreement is not identical to collusion under U.S. antitrust laws, the language and case precedence track similarly. Under antitrust law, mere parallel behavior among competitors is not enough to trigger a violation. But, parallel behavior along with a plus factor is sufficient.

Put another way, the mere fact that everyone is acting in the same way isn’t enough on its own to trigger a violation of the CBA’s collusion language. That’s doubly true in arbitration, because as we’ve discussed before, MLB teams are allowed to coordinate their arbitration filings. Per Jeff Passan:

While MLB works diligently and impressively to coordinate the arbitration targets of its 30 teams — this behavior is sanctioned under the collective bargaining agreement and not considered collusive — agents occasionally make far-under-target settlements. The effect, in a comparison-based system, is devastating: A bad settlement can linger and depress prices at a particular position for years.

But coordination of filings isn’t all that’s going on. As Carig explains:

Those versed in arbitration describe efforts that encourage teams to hold the line in negotiations, even when differences are relatively small, because the results will eventually have a larger impact in setting future comparables. In essence, it is worth fighting for pennies, because even pennies pile up over time. The labor relations department positioned itself as a central resource. It made data available for teams to more easily find comps to be used in negotiations. It staged mock arbitration sessions. It encouraged frequent discussion about the process. As a result, teams as a group have improved their approach to arbitration.

Eventually, the league began using its internal information to promote its own valuations for all players eligible for arbitration. These are still, technically, recommendations. But according to several people familiar with the process, they have increasingly been treated as hard guidelines. It is understood that teams are to settle at or below the league’s recs.

Now, a lot of this is above-board. Coordination of arbitration figures is allowed by Section 2 of the part of the Collective Bargaining Agreement that governs salary arbitration, which states that, “It shall be the responsibility of the Association prior to the Exchange Date to obtain the salary figure from the Player, and the LRD shall have a similar responsibility to obtain the Club’s figure.” That “LRD” is the league’s Labor Relations Department. So this clause, by its plain language, allows for the LRD to talk to the club about what its filing is going to be – after all, how else would the LRD obtain the figure? In fact, as attorney Michael D’Ambrosio explained, it’s the LRD that submits the team’s proposed salary figure. The CBA also allows for LRD to select arbitrators on behalf of teams, and designates LRD as the recipient of arbitration awards along with the team, the player, and the union. That’s because the LRD is also tasked by Major League Baseball with “look[ing] at results across cases to analyze the consistency of outcomes.”

In short, there’s nothing wrong with LRD being involved in the salary arbitration process. Major League Baseball is even right now hiring for an attorney to assist teams in preparing for and presenting arbitration cases. Holding mock arbitrations? Providing data? Facilitating communication? All fine. The CBA bars none of those things. The CBA doesn’t even prohibit awarding a schlocky plastic belt for stupid reasons, but there’s no law against stupid behavior. What the CBA does prohibit is the LRD stepping out of its role as a helper and into the team’s role as a party.

Here, the key fact isn’t the piece of plastic, though that’s certainly the most eye-catching. Instead, the most important fact is Carig’s reporting that MLB’s recommendations are being treated as “hard guidelines.” Per Carig:

“The LRD is definitely pushing a narrative that recs are concrete. And going above the rec is a substantially bad thing to do because it will mess up this entire salary structure.”

Remember, the CBA says that the LRD can help teams in arbitration. What the CBA doesn’t allow is for LRD to make final decisions. LRD can help a team develop a submission, but it can’t tell a team what its submission figure should be. It can help a team prepare for a hearing, but it can’t tell the team it must have that hearing instead of settling. It’s a subtle but important distinction. Think of LRD as a person sitting next to you in a car. It can read you a map. It can read you the directions from your smartphone. It can tell you what direction you’re driving in. But it can’t take over the steering wheel or force you to slam on the brakes. The question then is whether meetings like those Carig reported mean that LRD is the driver or the passenger:

For the league, it begins in spring training, when they hold State of the Union-style debriefings — two in Arizona and two in Florida — to evaluate the just-completed arbitration cycle. Attendees are presented with a 90-page booklet filled with data such as each club’s adherence to the league’s recommendations, the timing of all settlements, and a preview of the work to come. This spring, it also included a section of media quotes regarding arbitration. One in particular was highlighted in red, [agent Jeff] Berry’s line about “successfully stagnated arb salaries.” To this point, the executive leading the session offered a confirmation, and encouraging words about the progress being made.

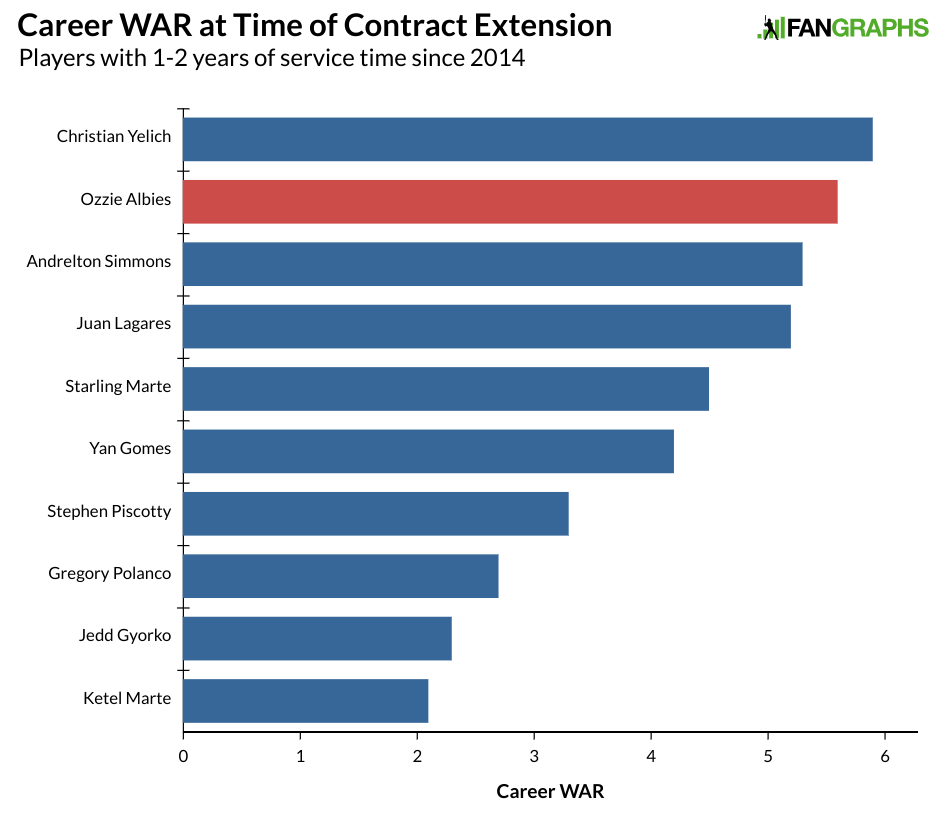

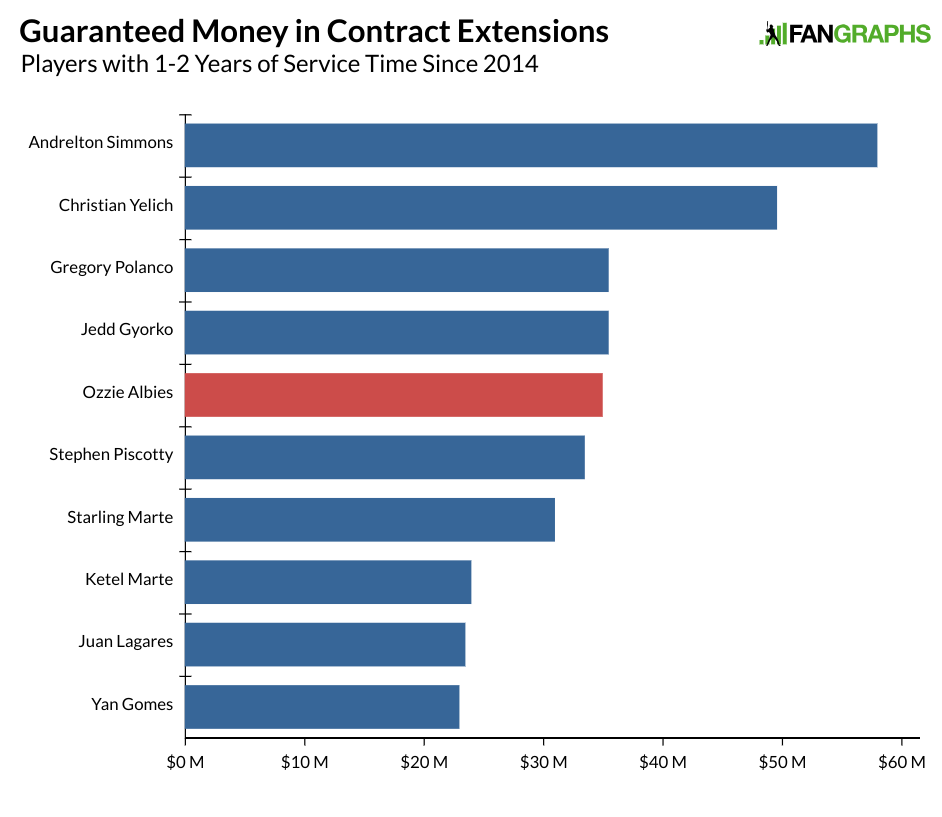

If LRD really is stepping over that line – taking control of the arbitration process instead of merely providing assistance – we would expect to see some empirical data on that point. Notably, Deadspin found that “Nearly two-thirds of settlements have come in at or below the labor relations department’s ‘recommendations,’ up from less than half a few years ago.” At the same time, Carig noted that “there are no tangible repercussions for teams that break ranks.” And though Carig also added that “some teams find themselves feeling compelled to go along with the league’s plan, and fighting with their own players in the process[,]” he doesn’t say how.

Unfortunately, the CBA never actually specifies the evidentiary showing necessary to prove collusion. Per Heitner and Postal, “The Basic Agreement does not provide what burden needs to be met in order to prevail in this type of grievance.” Nevertheless, we can use what we know about antitrust law to make some educated guesses.

Courts evaluate most antitrust claims under a “rule of reason,” which requires the plaintiff to plead and prove that defendants with market power have engaged in anticompetitive conduct. To conclude that a practice is “reasonable” means that it survives antitrust scrutiny.

(Because the standards are similar, we can look at what antitrust law considers collusive or anticompetitive behavior in interpreting MLB’s own collusion clause; this does not mean that MLB isn’t subject to an anti-trust exemption, which is a different issue entirely.)

Why a reasonableness standard? Because, theoretically, everything is a restraint on trade, and to an extent, everything is collusive, too. Every trade between teams is a coordinated attempt by those teams to set the value of players. Trading James Paxton for Justus Sheffield (and other prospects) means that James Paxton is worth Justus Sheffield (and other prospects), and future trades will use that as a referent. Exchanging J.T. Realmuto for Sixto Sanchez and Jorge Alfaro means that the Phillies and Marlins, two enterprises that are supposed to be in competition with one another, have fixed the price of a J.T. Realmuto at a Sixto Sanchez and a Jorge Alfaro. In a sense, those trades are themselves anti-competitive, because it means that the value of similar players has been set, and the players who were traded have been removed from the market. But no one would say those trades were an unreasonable restraint on competition. The Red Sox can’t file a grievance because the Yankees and Marlins “colluded” on Giancarlo Stanton.

It’s for these reasons that subjective intent isn’t necessarily a good indicator. As such, we aren’t going to discuss whether or not the LRD and teams think they’re colluding. For example, the Supreme Court said in a case called Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n v. Bd. of Regents of Univ. of Oklahoma that when we’re looking at whether something is unlawfully collusive, we can base our conclusion “either (1) on the nature or character of the contracts, or (2) on surrounding circumstances giving rise to the inference or presumption that they were intended to restrain trade and enhance prices.”

Legal test aside, there’s a factual problem with using subjective intent: we don’t always know what other people are thinking. For all we know, the Giants’ arbitration team does its work while thinking about Chicago deep-dish pizza. So instead, we’ll follow a rule from a 1913 case called United States v. Patten that we don’t need to prove specific intent: “by purposely engaging in a conspiracy which necessarily and directly produces the [anticompetitive] result which the statute is designed to prevent, they are, in legal contemplation, chargeable with intending that result.” (It also is possible to do something so anti-competitive that the law presumes the action to be unlawfully collusive, but that’s unlikely to be the case when we’re talking about a piece of plastic.)

To understand why all of this matters, it’s helpful to look at baseball’s collusion cases from the 1980s.

After the 1985 season, at the urging of Commissioner Peter Ueberroth, owners came to an unwritten agreement not to compete with each other over the services of free agents, and to reduce significantly the length of contracts they would offer. As a result, free agents were forced to re-sign with their original teams for little or no pay raise, unless their team indicated that it was not interested in their services.

The union’s grievance eventually resulted in a $280 million arbitration award in favor of the players, and an award of free agency for seven players. In some ways, the similarities between the collusion of the 1980s and today are striking. For example, that “unwritten agreement” mentioned above was couched in terms of fiscal responsibility and avoiding long-term contracts, rhetoric that would be familiar to anyone who follows a front office today. But then, the owners went further than that.

Then at the Winter Meetings in San Diego that winter [1985-86], the idea of “fiscal responsibility” was preached to ownership. A list of the 62 players who filed for free agency was circulated to all teams and a message was sent to avoid the free agent market until a player was “released” by their former club, meaning a team would have to make it public that a player no longer fit in their plans. If all teams participated in the plan, the free agent market would no longer be free, but it would be controlled by the teams.

That’s the part that was found to be collusive by an arbitrator. What does this have to do with a plastic wrestling belt? Take a look at what then-MLB Commissioner Peter Ueberroth said to owners ahead of the 1985-86 offseason.

“If I sat each one of you down in front of a red button and a black button and I said, ‘Push the red button, and you’d win the World Series but lose $10 million; push the black button, and you would have a $4 million profit, and you’d finish in the middle,’ you are so damned dumb, most of you would push the red button. Look in the mirror and go out and spend big if you want; don’t go out there whining that someone made you do it.”

In closing, Ueberroth told the owners: “I know and you know what’s wrong. You are smart businessmen. You all agree we have a problem. Go solve it.”

That’s a directive from the commissioner of baseball to not spend on free agents. As soon as Ueberroth made this statement, what could have been passed off as benign instantly became legally something more sinister. That we now have sources implying that LRD is dictating salary arbitration submissions and strategies, all for a uniform purpose, does potentially suggest a situation with at least some parallels to the 1980s.

That said, there are a number of significant differences between Ueberroth’s speech and this plastic wrestling belt. For one thing, Ueberroth gave a de facto instruction. As far as we know, no one has given a similar speech regarding arbitration. Even the comments regarding “progress” made in “stagnating arbitration salaries” aren’t in and of themselves damning; the comments weren’t tied to team revenues the way Ueberroth’s were, and didn’t, in and of themselves, suggest an instruction or implied agreement. Moreover, even assuming that all teams agreed that arbitration salaries should be lowered to improve profits, complimenting those teams on having already done so doesn’t mean that those efforts were collusive from the beginning.

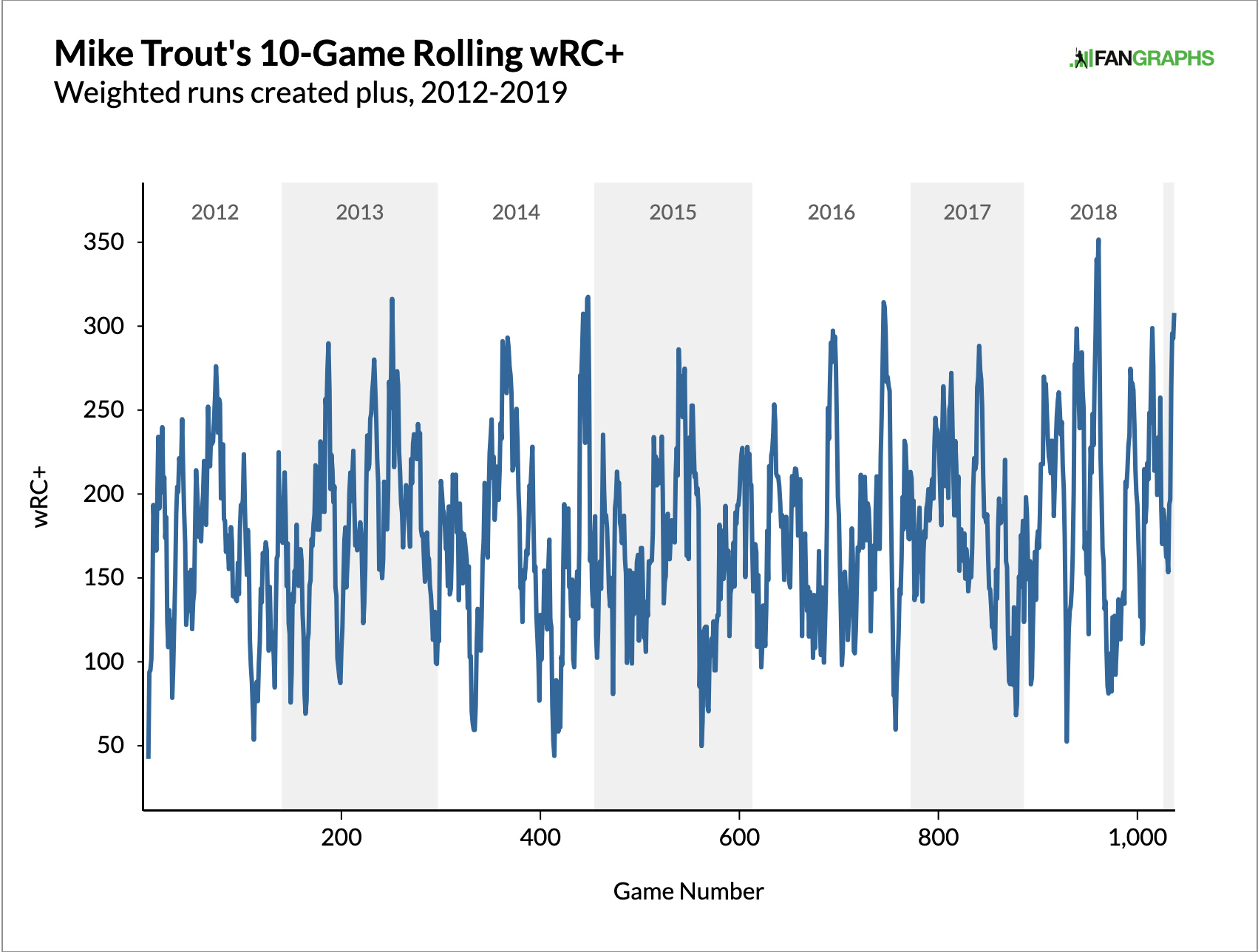

So while the MLBPA might have new grist for a collusion grievance based on Carig’s reporting, we’re a long way from the union being able to prove such a case. Proving collusion from a legal perspective is very difficult hard. For example, Barry Bonds couldn’t find a job after posting a 157 wRC+ and .276/.480/.565 triple-slash with a BB% of 27.7% in 2007. He lost a collusion grievance in 2015, with one well-known labor union attorney noting that “I don’t believe that there is sufficient evidence, at least not public evidence, that there was a concerted effort to blackball him. I would be very surprised to see him prevail in this case.” That’s despite the fact that several well-known labor attorneys continue to think Bonds’ grievance had merit.

That said, the ramifications of this development are potentially significant beyond a legal case. First, this puts the league’s recent concession regarding a 26th roster spot in an entirely new light, particularly if the league knew ahead of time that this was about to break. Second, this changes the dynamic between the league and union from that of a potential thaw in relations to being on the precipice of a possible work stoppage. One veteran told Carig he was “ready to strike tomorrow.” Players across the league reacted similarly.

Astros ace right-hander Gerrit Cole:

We understand business, but if you were looking for a way to antagonize players, this would be a great way to do it,” Cole told The Chronicle on Saturday. “If it’s not intentional, it certainly is a pretty fascinating move by them because I don’t think there’s one player in this room that’s worked hard for his salary through arbitration or gone through the process and taken it seriously like I have or Collin [McHugh] has that really wants to kind of be treated with a lack of respect.”

An MLBPA spokesperson referred me to Executive Director Tony Clark’s official statement:

Major League Baseball did not respond to my request for comment.

We can’t say with any certainty whether MLB’s actions are legally collusive, nor whether the MLBPA would have a viable claim based on these facts. But as reported, LRD’s actions suggest that they may have gone beyond the role the Collective Bargaining Agreement defines for them in the arbitration process. How the union chooses to react to these facts remains to be seen, but they could constitute a significant development in the game’s ongoing labor conflict, and could deepen the rift between the union and MLB.