The Run Expectancy Matrix, Reloaded for the 2020s

This is a public service post of sorts. If you’re like me, when you type “Run Ex” into Google, it will auto-complete to “Run Expectancy Matrix.” It knows what I want – a mathematical description of how likely teams are to score in a given situation, in aggregate. I use this extensively in analysis, and I also use it in my head when I’m watching a game. First and third, down a run? That’s pretty good with no outs, but isn’t amazing with two.

There’s just one problem with that Google search: It’s all old data. Oh, you can find tables from The Book. You can find charts that are current through 2019. There’s a Pitcher List article that I use a lot — shout out to Dylan Drummey, great work — but that’s only current through 2022. And baseball is changing so dang much. Rather than keep using old information, I thought I’d update it for 2025 and give you some charts from past years while I’m at it, so that you can understand the changing run environment and use them for your own purposes if you so desire.

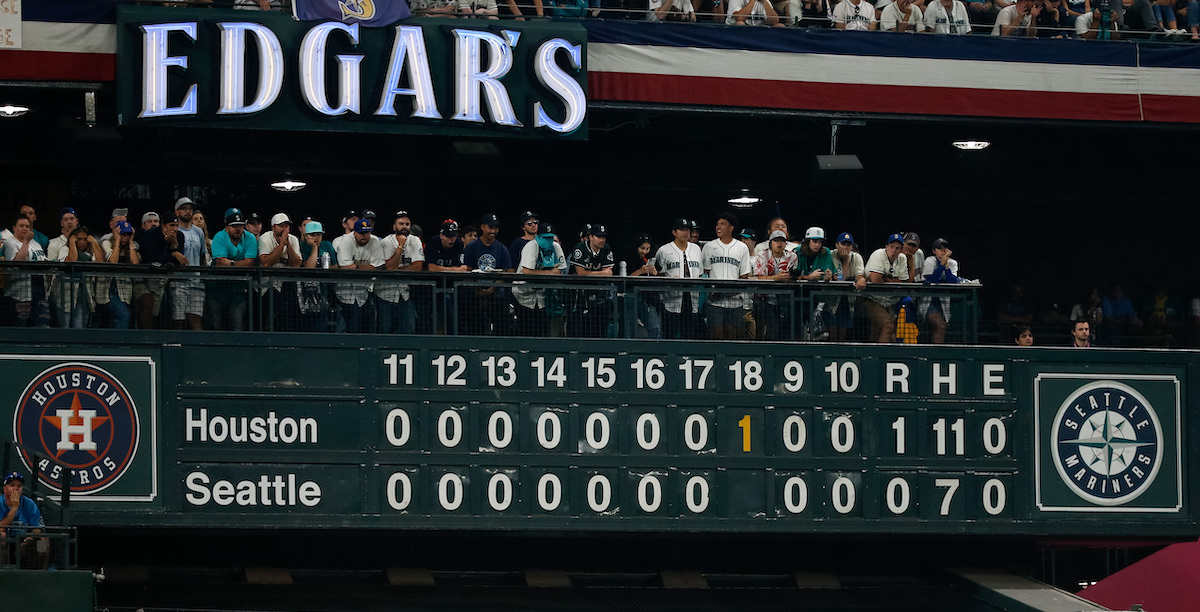

First things first: Let’s talk methodology. I downloaded play-by-play logs for all regular season games played between 2021 and 2025. For each play, I noted the runners on base, the number of outs, and then how many runs scored between that moment and the end of the inning. I did this for the first eight innings of each game, excluding the ninth and extras, because those innings don’t offer unbiased estimates of how many runs might score. Teams sometimes play to the score, and the home team stops scoring after the winning run. If you have the bases loaded and no one out in the bottom of the ninth, one run will usually end it, and that provides an inaccurate picture of run scoring. That’s also why I skipped 2020; the seven-inning doubleheaders and new extra innings rules produced a pile of crazy results, and the season was quite short anyway. No point in trying to wade through that maze. Read the rest of this entry »