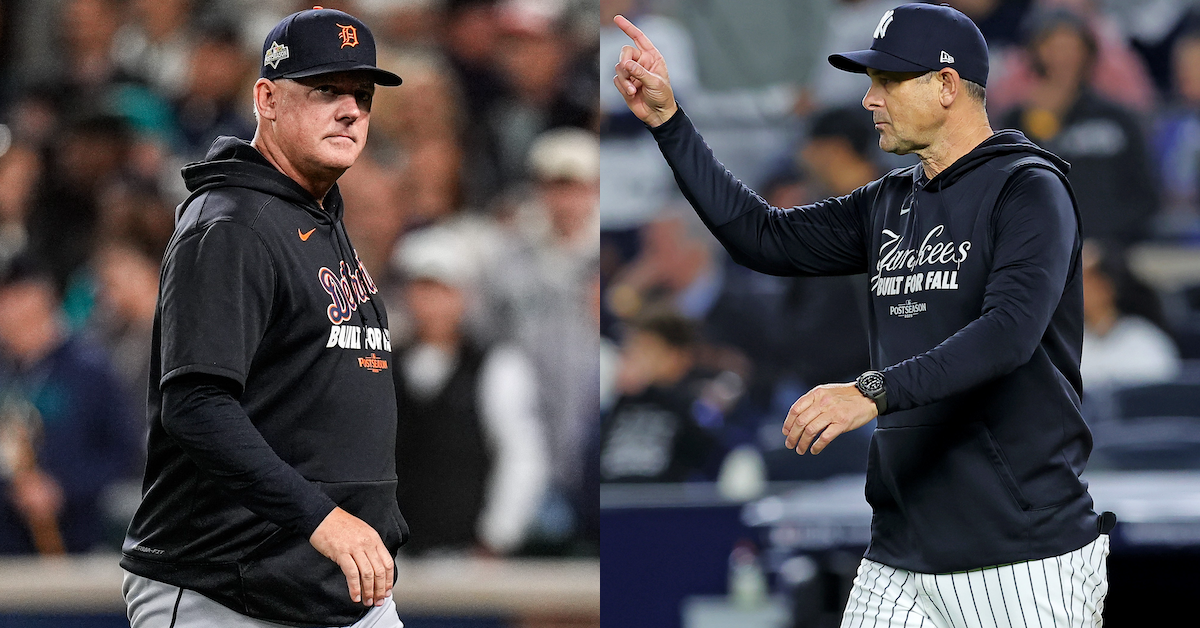

Postseason Managerial Report Cards: Aaron Boone and A.J. Hinch

I’m trying out a new format for our managerial report cards this postseason. In the past, I went through every game from every manager, whether they played 22 games en route to winning the World Series or got swept out of the wild card round. To be honest, I hated writing those brief blurbs. No one is all that interested in the manager who ran out the same lineup twice, or saw his starters get trounced and used his best relievers anyway because the series was so short. This year, I’m skipping the first round, and grading only the managers who survived until at least the best-of-five series. Today, we’ll start with the two managers who lost in the American League Divisional Series, Aaron Boone and A.J. Hinch.

My goal is to evaluate each manager in terms of process, not results. If you bring in your best pitcher to face their best hitter in a huge spot, that’s a good decision regardless of the outcome. Try a triple steal with the bases loaded only to have the other team make four throwing errors to score three runs? I’m probably going to call that a blunder even though it worked out. Managers do plenty of other things — getting team buy-in for new strategies or unconventional bullpen usage behind closed doors is a skill I find particularly valuable — but as I have no insight into how that’s accomplished or how each manager differs, I can’t exactly assign grades for it.

I’m also purposefully avoiding vague qualitative concerns like “trusting your veterans because they’ve been there before.” Playoff coverage lovingly focuses on clutch plays by proven performers, but Cam Schlittler and Michael Busch were also great this October. Forget trusting your veterans; the playoffs are about trusting your best players. Blake Snell is important because he’s great, not because of the number of playoff series he’s appeared in. There’s nothing inherently good about having been around a long time; when I’m evaluating decisions, “but he’s a veteran” just doesn’t enter my thought process.

I’m always looking for new analytical wrinkles in critiquing managerial decisions. I’m increasingly viewing pitching as a tradeoff between protecting your best relievers from overexposure and minimizing your starters’ weakest matchups, which means that I’m grading managers on multiple axes in every game. I think that almost no pitching decision is a no-brainer these days; there are just too many competing priorities to make anything totally obvious. That means I’m going to be less certain in my evaluation of pitching than of hitting, but I’ll try to make my confidence level clear in each case. Let’s get to it.

Aaron Boone

Batting: A

Boone’s first game of the playoffs brought an immediate, consequential decision: How many left-handed batters should he play against Garrett Crochet? He leaned into platoon matchups to the greatest extent possible, and I thought it was definitely the right choice. Crochet pitches deep into games and the Red Sox bullpen featured a lefty closer and several other good southpaw options. Even better, the few righties were surely reserved for the Aaron Judge section of the lineup, so Boone’s right-handed platoon bats were likely to get relatively good matchups all evening. That plan worked – well, “worked.” Amed Rosario and José Caballero, two right-handed substitutes, both went 0-for-3, while Paul Goldschmidt led off and collected two hits, and the Yankees lost 3-1. But the idea! Excellent.

Game 2 saw Boone switch to his normal lineup, with Trent Grisham leading off and Ben Rice, Jazz Chisholm Jr., and Ryan McMahon all making their first starts of the series. Boone also made a decision I liked, sticking with the lefty bats even when Boston manager Alex Cora used some lesser lefty arms against them. When the Red Sox went to multi-inning monster Garrett Whitlock, a righty, in a tie game, the Yankees still had their best lefties in the game. Cora couldn’t swap Whitlock out for a lefty without letting the Yankees send in their entire bench of righties, so Whitlock stayed out there and got beat by two lefties for the game-winning run. Great patience by Boone here.

The Red Sox started another lefty in the win-or-go-home Game 3, but rookie Connelly Early was clearly only going to be in the game for a short stint, so Boone hybridized his lineup, benching McMahon but keeping the rest of the lefties. Those lefties did a great job reminding managers that platoon advantages aren’t the only thing that matters. Chisholm, Cody Bellinger, and Austin Wells were all at least league average against southpaws this year, and all of them reached as the Yankees put up four runs in the fourth. But the righty Boone plugged in did work too; Rosario’s RBI single was the hit that broke the inning open. After that, Boone played pretty normally – McMahon as a defensive substitution, Goldschmidt pinch-hitting and then staying in for defense – and put the game away.

The Blue Jays brought an all-righty rotation to the ALDS, which meant Boone spent most of the series putting his favorite lineup in and letting it go to work. The first game of the series didn’t have a single interesting decision on this side of the ball. The second game was more of the same; Trey Yesavage struck out 11 Yankees while the Jays put up a 13-spot. I did like that Boone swaddled Judge in lefties, with one in front of him and two following, which meant Toronto manager John Schneider was frequently putting in lefty relievers to face the greatest right-handed hitter on the planet. When Schneider tried to break that pattern by bringing his lefty well in advance of Judge and planning on removing him when Judge batted, Boone countered by using Goldschmidt as a pinch-hitter, another move I liked. In the third game of the series, the only one the Yankees won, he went with his favorite lineup and then brought in Rosario to pinch-hit for McMahon with runners on base and a lefty freshly in the game.

That just leaves the finale, where Boone finally shook things up. With the Jays opting for a bullpen game, Boone rearranged his lineup to alternate left/right all the way down. That made the Jays’ plans slightly more awkward; more relievers came in mid-inning, more tired relievers had to stay just for one extra batter to make the matchups work, and despite Schneider’s maneuverings, Judge and Goldschmidt each got opportunities to face lefties. When Toronto went to its high-leverage righty arms, Boone was then able to replace Goldschmidt with lefty Ben Rice. I think that Boone generally did a great job of getting the most out of his lineup. He used Judge’s strategy-warping gravity to force other teams to choose between bad matchups. He got good matchups for his righty bench bats. It still wasn’t enough; sometimes that happens.

Pitching: B+

Boone’s first decision of the postseason came early. Max Fried, his ace, made it one batter into the seventh before Boone went to Luke Weaver against Boston’s righty-heavy lineup. With Fried 102 pitches in and about to face the Boston lineup for a fourth time, Boone tried to find Weaver a low-risk spot to get right against Boston’s eighth and ninth hitters. Weaver had struggled in September, and really hadn’t looked like himself all year, but the Yankees didn’t have a deep enough bullpen to just ignore him. Plus, he’s a really good pitcher — he was their closer just last year. Relievers are hot and cold all the time, unfortunately, and maybe this was the time when he’d get hot again. Turns out, it was not, but the thinking made sense even though it didn’t work out. Weaver got lit up for a walk and two no-doubt hits, and it was quickly 2-1 Red Sox. Boone quickly adjusted by removing Weaver and turning to Fernando Cruz, and then leaned heavily on the back of his bullpen to keep the game close. Devin Williams, David Bednar, and Tim Hill all followed, which meant the Yankees went through all of Boone’s favorites in a 3-1 loss. I thought this was logical, too. In a three-game series, you can’t just punt the first game because you’re down a run.

With another chance at the same game plan, Boone adjusted. He gave Carlos Rodón the same rope he’d given Fried, extending him into the seventh inning looking for a matchup against lefty Jarren Duran. It didn’t work, but I liked using Rodón as a de facto bonus LOOGY, and Boone went to Cruz instead of Weaver to face the post-Duran stretch of righties, preventing hitters from getting multiple looks at both pitchers. Cruz wriggled out of a two-on, none-out jam. Williams got the eighth, also facing different batters than he had in the first game, and Bednar closed out the win. Boone had all hands on deck for the last game of the series, but Schlittler made it a moot point by shredding the Boston lineup for eight innings. Schlittler even made Boone’s decisions easy; he retired the last nine batters he faced, with a four-run lead the entire time, so Boone just let him go until it was time for Bednar in the ninth. Just because the decision was easy doesn’t mean it wasn’t right; Boone played it right down the middle and profited here.

Against the Blue Jays, the sledding got tougher. Luis Gil started the first game as a glorified opener. He lasted eight outs and 12 batters, giving up two solo shots and departing as soon as Boone could find a good lefty matchup for Hill. The best spot for Hill was surely the Addison Barger/Alejandro Kirk/Daulton Varsho section; two lefties in three batters, a righty with muted platoon splits in between, and no requirement to let your soft-tossing southpaw face Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Hill did the job and even stayed in for two bonus batters (switch-hitter and lefty) before Camilo Doval got the scary part of the Jays order. Then it was Weaver’s turn – and as he did in Game 1 against Boston, he let all three batters he faced reach, sending Boone back to the pen for Cruz. Cruz let all the inherited runners score and even surrendered a fresh run of his own. With the game all but over, that meant Paul Blackburn drew mopup duty, and wore four runs while finishing up the game.

In theory, Boone now had a big problem: He couldn’t trust Weaver, his top reliever from last year’s playoffs. In practice, it didn’t matter right away, because Fried got absolutely lit up in Game 2. The Jays scored five runs in the first three innings, then put their first two batters on in the fourth. That brought up the top of the lineup for a third time, and Boone had to act given Fried’s declining form. He brought in Will Warren, a starter who could provide bulk innings – and Warren gave up two homers in his first five batters faced, which pushed the score to 11-0. He then transitioned to mopup duty, sticking around for 14 outs in total. Weaver got the last Toronto batter of the game and finally recorded his first out of the playoffs.

Boone had his back against the wall for the next game, and Rodón looked even shakier than Fried; nine of the first 16 Jays to bat reached safely. Boone could have been even more aggressive in relieving Rodón; he left him in for three straight RBI singles at the end. I thought it was entirely defensible to give him a few extra batters, and I liked that Boone followed by going to Cruz — a high-leverage reliever who hadn’t been overexposed to the heart of the Toronto order — right away. Cruz steadied the ship, Doval took the baton next, and Hill followed against a two-lefty pocket. That set up Williams for his first crack at the middle of the Toronto order, and he was perfect. Bednar followed him, also in his first action of the series, and closed out the win. Boone did a great job here of getting the guys who were currently doing the best into the game in situations where they were well suited.

Game 4 was another Schlittler outing, but it wasn’t the same dominant Schlittler from last round. Toronto scratched out a run in the first, then brought the top of the order up for a third time in the fifth inning. The situation was a tough one: runners on first and third with no one out, all of Toronto’s best hitters due up, and enough outs remaining that Boone would need to face the best Blue Jays hitters at least twice more, and probably three times. All of his high-leverage guys had already seen Guerrero and George Springer at least once in the series, and Cruz had already seen them twice. Boone opted to leave Schlittler in, a decision I liked given how the rest of the game stacked up, and Schlittler rewarded him by escaping the jam with only a single run allowed.

I’m less keen on leaving Schlittler in for the sixth, against the Barger/Kirk/Varsho section of the lineup that seems tailor-made for Hill, but that felt like a pretty marginal decision either way. Boone went to Williams when the top of the order rolled around again in the seventh, and Williams just got beat by Nathan Lukes on a pretty decent fastball. Next up was Doval, and he let three of the four batters he faced reach, so Boone hit the big red button and had Bednar pitch the rest of the game. Bednar got the job done, but the Yankees never got their offense going, and a 5-2 loss ended their October.

Despite the outcome, I thought Boone did a very good job managing. There’s a temptation among Yankees fans to turn every year into an apocalyptic referral on whether this iteration of the squad is hopelessly doomed. The headlines after this year’s exit look quite bad! I understand that for a team with 27 world championships, the bar is pretty high. Let’s just say that short of having better players, I don’t think Boone could have done anything else to make this playoff run go better. The Red Sox and Blue Jays are both really good teams; going 3-4 against them is just going to happen sometimes.

A.J. Hinch

Batting: A+

Hinch’s most important decision on the offensive side of the ball was deciding how often to let Kerry Carpenter, a dominant lefty hitter who hasn’t performed well against lefties in his career, face left-handed pitching. The manager opted for as much Carpenter playing time as possible; Erik Sabrowski came in to face Carpenter in the eighth inning of the playoff opener, and Hinch stuck with his guy. Carpenter struck out, but we got an insight into Hinch’s mindset right away. We also got a preview of how willing he was to make unconventional decisions when he called for a squeeze bunt with one out and runners on the corners in a 1-1 tie in the seventh inning. I loved that decision with Tarik Skubal on the mound; the Tigers cashed in a run and never looked back.

In the second game of the Wild Card Series, Hinch notably pinch-hit for Riley Greene, a decision I’ve already covered. I thought it was perfectly reasonable, even if it looked strange at first glance, a 50/50 decision more or less. It didn’t matter much; the Tigers scored only one run and got shellacked. Hinch made a slight change for Game 3, moving Parker Meadows from leadoff to ninth and shifting the rest of the lineup up. The idea was to get Carpenter more plate appearances while still protecting him with righties to make the other manager choose between two tough choices. The Guardians countered with a lefty specialist, Tim Herrin, by the third inning. Hinch stuck with Carpenter, who hit a tie-breaking double. Hinch didn’t have to make many other decisions on the batting side, though; a splash inning against Hunter Gaddis put the Tigers up 6-1, and that was that.

Against the Mariners, Colt Keith returned from injury to give Hinch a fearsome core of lefty hitters. Seattle’s starters are all righties, so Hinch jammed the top of his lineup with his guys: Carpenter second, Greene third, Keith fifth. I’m a big fan of this move. I’m also a fan of Hinch pulling Keith for lefty-killing Jahmai Jones as soon as the Mariners brought a lefty reliever into the game. Finally, I liked that Hinch stopped tinkering, aside from pinch-hitting for Jones with switch-hitter Wenceel Pérez, after that; he didn’t have any other excellent pinch-hitting options, and the Mariners were only carrying two lefties in their bullpen, so there was no reason to get a so-so righty into the game for one solitary at-bat unless it was a particularly important one.

Hinch mostly held to his Jones-first, patient-after style of pinch-hitting for the entire series. When he made a change, it was a reasonable one: Keith matched up against lefty Gabe Speier in Game 2, but Speier had already faced three batters, so a Jones appearance would’ve just brought a righty out of the pen. Instead, Hinch went to Pérez so that he was guaranteed a platoon advantage in the matchup. Pérez popped out weakly, but I loved the move either way.

As the rest of the Tiger lineup continued to sputter, Hinch kept moving Carpenter up in the order, batting him leadoff when the series shifted back to Detroit. Aside from a Meadows bunt that I’m not sure was even called from the dugout, Hinch stuck to his plan. He didn’t use any pinch-hitters at all until Caleb Ferguson entered in the ninth. Then he emptied the bench, three pinch-hitters in four batters, to engineer a rally when all three replacements reached. The only problem? The Tigers were down 8-1 at the time, and that rally wasn’t enough.

You’ll never guess what happened in the next game. Well, you probably will, actually, because Hinch was metronomic in his usage. Speier came into the game, Hinch brought in Jones for Meadows, and Jones delivered, this time with a tie-breaking RBI double. After that, Hinch stuck with his starters, even allowing Keith to bat against Speier with two outs and a runner on third. Keith grounded out to end the inning, but when Hinch let Greene face Speier to begin the next inning, the 25-year-old left fielder rewarded his manager with a solo homer off of Speier, and then the rest of the Tigers teed off to send the ALDS to a concluding game.

You might expect a 15-inning contest to lead to a ton of offensive substitutions, but Hinch wasn’t having any of it. The Mariners brought Speier into the game in relief of George Kirby, but Hinch stuck with Carpenter, and Carpenter hit a two-run homer to flip the game from a 1-0 deficit to a lead. That led Hinch to hold Jones in reserve, secure in the fact that the Mariners weren’t going to use a second lefty when a spectacular substitute was just waiting to check in. The Tigers got the matchups they wanted the rest of the night. The only problem was that everyone other than Kerry Bonds was ice cold; Carpenter went 4-for-5 with two walks and a homer, while the rest of the team went 4-for-46 with two walks of their own.

I loved Hinch’s decision-making here. He knows how to use a limited bench, particularly in the context of a platooned lineup. He got a ton of use out of Jones being the big bad wolf, more or less, who could come in and blow any lefty specialist’s inning down. That let Hinch roll with his preferred lineup for longer. I would have been interested to see how Hinch handled an opponent with more lefties in the bullpen, but I can only grade him on what he did, and I thought he did incredibly well here.

Pitching: C+

How long should you leave Skubal in? As long as he wants to go. That was 7 2/3 innings in the playoff opener against the Guardians, with Will Vest taking the last four outs. Hinch aced that test. Unfortunately, “How long should you leave Casey Mize in?” is a much tougher follow-up question, and Hinch seemed to have made up his mind in advance that Mize wasn’t going to see the good lefty section of the Cleveland lineup twice. Tyler Holton, a multi-inning lefty option, retired seven batters to bridge the game to the sixth inning, where Hinch could deploy his normal relief strategy.

That normal relief strategy contained a fresh wrinkle for the playoffs: Kyle Finnegan as a fireman. Finnegan was one of the revelations of the trade deadline, a rock solid closer who propelled the Detroit bullpen, but after a September IL stint, Hinch made him a multi-inning option instead. He got the toughest part of Cleveland’s order, or in other words, José Ramírez plus some guys. With Finnegan’s job done, Hinch brought in Troy Melton, a high-octane starting pitcher prospect the team used in relief in his rookie year. He just didn’t have it, to the tune of three straight one-out extra-base hits to put the game away.

An elimination game showed us Hinch’s true bullpen pecking order. When starter Jack Flaherty started to lose steam – three of the last six batters he faced reached base, and the top of the order was fast approaching – Hinch called on Finnegan to get those dangerous hitters again. He did his job, and Holton followed by getting the same pocket of lefties again. With a 6-1 lead, Hinch tried to use Tommy Kahnle, a member of the low-leverage bullpen crew, but Kahnle let two of his first three opponents reach, so Hinch just said to hell with it and brought in Vest to close things out.

The Mariners were a different puzzle entirely than the low-offense, high-scrappiness Guardians. A longer series also meant that Hinch needed to open up his bullpen hierarchy. So in the first game of the ALDS, he gave Melton the start with a short leash. Unless Melton was gassed after 57 pitches, I thought Hinch took him out too early, as he was pitching quite well, but I think Melton was probably limited given that he’d thrown in relief two days earlier. Rafael Montero got into his first game action here as a righty specialist, but whoops, all three batters he faced reached base, so it was back to the old crew quickly. Holton came in first, Kahnle followed, then Finnegan replaced him for the top of the order. Vest contributed two innings of his own, with the game lurching into extra innings. The last trusted man standing was Keider Montero, a swingman by trade, and he pitched an uneventful inning to move up Hinch’s list of trust and also earn the save.

Game 2 was another Skubal game – seven innings and 97 pitches is what he had, so Hinch said “OK cool” and then tried to cover the last two from there. Finnegan came in to face the scary part of the lineup for the second time in a row, and this time he wasn’t up for it; Cal Raleigh doubled, Julio Rodríguez doubled him home, and Hinch eventually replaced Finnegan with Brant Hurter for a lefty/lefty matchup. I probably would have switched it up and used Vest against the top of the order if he was available, but it’s reasonable to think that he wasn’t after throwing two innings (albeit only 19 pitches) the previous night.

Finnegan was looking overexposed, so Hinch gave him the next game off. Flaherty looked sketchy, though, surrendering four hits and three walks in his first two trips through the order. At that point it was 3-0 Mariners, and with a runner on base and the top of the order due up, Hinch made a change. He brought in Kahnle, who allowed an inherited runner to score while wriggling out of the jam. Now in low-leverage mode thanks to the Detroit bats going cold, Hinch followed with Hurter, Montero, and mopup man Brenan Hanifee. Given that the next two games were going to be elimination contests, I like the instinct to preserve the bullpen here.

I understand Hinch’s plans very well from this point forward. Mize was scheduled for Game 4, Skubal for the decider. Hinch brought the entire bullpen out to help Mize. I think he could have demonstrated a bit more patience – he pulled Mize after only three innings, on plenty of rest, when Mize had racked up six strikeouts against only a single earned run. It wasn’t even the terrifying part of the lineup; Mize had just marauded his way through that group in the previous inning. I understand that Hinch was planning on using the entire bullpen that day and then getting an ace performance to ease the relief burden in the decider, but I think that sticking with Mize should have been a bigger consideration given how good he looked early.

In any case, Holton came in and got cooked – single, single, walk, call to the bullpen for Finnegan, who escaped with only a single run of damage and then stuck around to get the top of the order again. This time, Raleigh drove in a run to push the lead to 3-0 Mariners. Hinch’s next move was three innings of Melton, and man, were these innings of Melton that much better than just letting Mize go for longer? He even got most of the same batters Mize would have faced. Melton did great, to be clear, I just feel like Hinch underused Mize to start the game, and ended up tiring out his bullpen (three innings for Melton, another three between Finnegan and Vest, plus a Holton appearance) in a game where the Tigers scored nine runs and won comfortably against an exhausted Seattle bullpen. At the very least, I think I would have given Vest the night off. Did he really need to pitch the ninth inning with a six-run lead?

In Game 5, “Skubal for as long as he can last” turned out to be six magnificent innings, comprising 99 pitches and an electric 13 strikeouts. Unfortunately, the regular reliever contingent was absolutely overworked now. Finnegan allowed two out of four batters to reach, and when the Mariners brought in a lefty pinch-hitter, Hinch countered with Holton out of the bullpen. That let Seattle bring in Leo Rivas as a pinch-hitter for the pinch-hitter to wrest the platoon matchup back. Truth be told, I didn’t hate this set of changes; Holton just needed to win against the rarely used Rivas, and instead he gave up a game-tying single.

You can see the rest of Hinch’s plans: Two innings for Vest brought him up to nine innings total, even with Skubal only going six. The problem was that this game was still tied, which meant it was time to throw everything at the wall and see who had something left. Melton pitched an inning. Montero followed with two of his own. Flaherty followed, giving everything he had on what would normally be a throw day. Finally, Hinch turned to Kahnle because he lacked other options. Kahnle drew the top of the Seattle order and couldn’t hold it down, sealing a 15-inning, 3-2 defeat that ended Detroit’s season.

I think that Hinch’s greatest strength and greatest weakness this October were inextricably linked. He did a great job of planning strategically around the Skubal starts and thinking about how that would affect his entire bullpen. I happen to think that he took that planning too far, though, and that his confidence in Skubal made him too willing to give the other starters a quick hook. That, in turn, meant a ton of Finnegan against the most dangerous part of the Seattle lineup, and I just hate that. Finnegan missed a lot of September hurt, and he didn’t look great upon his return. Here, go face Cal Raleigh a bunch to get right, Kyle, you’re welcome.

Getting 10 1/3 innings of starting pitching in the three games that Skubal didn’t go ended up being a big problem for Detroit. Maybe a team with an elite bullpen could have pulled that off, but Hinch was constantly trying to make moves to hide the fact that his group was more average than great. He put a ton of pressure on his top relievers to be perfect and his second-tier relievers to step up. Personally, I’d rather have more of those key innings come from Flaherty and Mize. Somehow, the Tigers started five games with pitchers other than Skubal, and they averaged less than four innings in those starts. That’s just too much work for a bullpen to cover. I’m not saying that Hinch would have prevailed in the series if he’d given his starters more room to work. I have no idea, of course. I think they still would have been fighting an uphill battle, but the path he chose made them less likely to win. I really liked a lot of his small tactical decisions, and I definitely think that he has a good handle on bullpen management and when to deploy his lefties, his high-leverage guys, his mopup types, and so on. I just think that the broad strategic plan didn’t lean enough on the non-Skubal starters.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

It sounds like you think Hinch did a great job of managing, especially on the offensive side, but perhaps he had too short of a leash on his starters. I’d agree that he was often removing a starter when the reliever was not necessarily an upgrade. The outcome didn’t always work out, but that was more of a talent/performance issue, than a managerial issue. This points to a clear need for the Tigers (Scott Harris) to upgrade some positions in the offseason, which will give Hinch the tools he needs to get the desired outcome.