Park Jong-Hoon is unique. If you need a quick introduction, look no further:

He is as true a submarine pitcher as one could be, which is quite rare in the current baseball landscape. Not only is he fun to watch, but he is also one of the top Korean-born pitchers in the Korean Baseball Organization (KBO). In 2018, he had his finest season yet, going 14-8, with a 4.18 ERA (125.8 ERA+) in 30 starts, striking out 133 in 159.1 IP. He also made the Korean national team for the 2018 Jakarta Asian Games and played a part in the Wyverns’ 2018 Korean Series championship. All in all, it was a big year. However, it seems that he has set his sights on an even bigger future.

This week, I sat down with Jong-Hoon at the Munhak Baseball Stadium, the Incheon home of the SK Wyverns, to talk about his development, his delivery, his pitches, and his desire to go to the major leagues. Originally, I intended to focus on his development as a submariner, but once he mentioned his big league ambitions, our conversation changed a bit.

On his development:

No one really starts out as a submarine pitcher. Neither did Park. When he was attending Gunsan Middle, his school’s baseball team needed a sidearm pitcher. The team’s manager asked his players to find the most flexible student they knew who was willing to throw a baseball. They recommended Park to him. “The team only had pitchers who threw with overhand or three-quarter slots,” Park said.

Once he got into the team, one of the drills he had to do required him to play catch while wearing a car tire on his back. “The training method in Korean amateur baseball is a bit old-school,” Park said. “At first, it was a small tire, but as the time went on, they gradually switched to bigger ones.” Because the tires got too heavy for his original posture, he lowered his posture while doing the drill. At some point, something clicked. “As I kept lowering my body, I felt that the arm slot started to fit me better,” he said. “We didn’t really have a pitching coach in our team, so I had to figure that all by myself.”

Unlike most other pitchers in the league, Park rose through the amateur system without any guidance of a pitching coach, which stunted his development until he went pro. In the second part of the KBO draft in 2009, Park was the ninth overall pick by the SK Wyverns. Despite his high draft slot, Park was far from feeling confident that he belonged there. “Once I got to the Wyverns, I felt that there were a lot of things I lacked,” Park said, “I soon learned that there were flaws here and there. In high school, I didn’t get to learn stuff like how to use my back leg, position my pelvis, consistently slot my arm, approach hitters mentally, etc.”

“I keep saying this over and over,” Park reiterates, “but it took so long for me to get to where I am. I wish I could get all that time back so I could have developed faster.”

Park’s rawness showed immediately. From 2011 to 2012, he appeared in just 15 games and gave up 17 walks, four hit by pitches, and 18 runs in 24.2 IP. After the 2012 season, Park opted to serve his mandatory military service and was admitted to play for the army baseball team. He returned to the Wyverns in September 2014 and started to see more action in 2015. That season, by the way, happened to be current Diamondbacks right-handed pitcher Merrill Kelly’s first year with the Wyverns. Kelly pitched for the Wyverns from 2015 to 2018, and earned a two-year major league contract with Arizona this past offseason. Park is appreciative of the four seasons he spent as Kelly’s teammate.

“I’m thankful for Kelly,” Park said, “he’s the reason why I came to appreciate and learn baseball deeper.” Through Kelly, Park learned new throwing routines, weightlifting methods, and mental approaches to hitters. He was also introduced to American baseball coaching books, which he read and studied by translating.

He has also tweaked his delivery over the years – it’s still a work in progress. When he got to the pros, he became aware of Chad Bradford and noticed a lot of similarities between them. Just like Bradford, Park threw from a very low arm angle, but Park also had a fast delivery tempo, again just like Bradford. In 2017, however, when the SK Wyverns had the former Arkansas Razorbacks coach Dave Jorn as their pitching coach, Park got a new homework assignment from him. “He told me to hold the motion momentarily before I go out to stride,” Park recalled, “once I made the adjustment, I was able to throw more accurately towards the target.” Park also mentioned that he still strives to make tweaks “here and there.”

However, Park credits something else for his improved command and overall performance. “What’s been more important is the mental side of pitching,” he said, “I’ve been really practicing my mentality: listening to good things, reading good things, if there’s a mental coaching lesson, I go out of my way to take it and I sometimes call sports psychologists for consultations. I’ve gradually improved after taking these steps.”

His efforts have shown. Here is how Park’s number progressed in the previous three years:

Park Jong-Hoon, 2016-2018

|

K% |

BB% |

K-BB% |

HR/9 IP |

ERA/ERA+ |

GB% |

| 2016 |

16.0% |

14.0% |

2.0% |

1.09 |

5.66/92.3 |

60.8% |

| 2017 |

16.1% |

9.2% |

6.9% |

0.95 |

4.10/122.7 |

56.1% |

| 2018 |

18.9% |

7.7% |

11.3% |

0.90 |

4.18/125.8 |

52.4% |

SOURCE: Statiz

His strikeout and walk numbers have noticeably improved. One could say that he traded some of his groundball tendencies for being able to throw strikes. Even so, Park has managed to keep the batted balls in the yard- his 0.90 HR/9 IP rate is the ninth best among all KBO starting pitchers last year, which is no easy feat in the league and especially at the Munhak Baseball Stadium. Munhak is known to be an extreme hitter’s ballpark with 311.7/393.7/ 311.7 foot outfield dimensions, meaning the left and right field fences are closer to home plate than the Yankee Stadium short porch. It will be interesting to see how his numbers trend in the 2019 season, but the recent history is promising.

On being a rarity:

Park has, indeed, thought about how things would’ve been had he thrown with a conventional overhand or three-quarter slot. “I think my development would have been easier if I were one. I’m confident that I would survive among other KBO pitchers with traditional deliveries – right now I can throw around 90, 91 mph with an overhand delivery,” he said, “but I still would have had to go through the same process.” He adds that being a submarine pitcher helped pave his way more easily than others. “I’ve been more about finding my own uniqueness instead of going with the cookie-cutter approach.”

Back when Park was learning to pitch, there wasn’t as much baseball content readily available online. He turned to watching a copious amount of television to find inspirations. Through that, he discovered other submariners around the world, like Bradford and Shunsuke Watanabe. “But to be honest, when I tried to research on more, they were all pitchers from a long, long time ago,” Park noted, “I learned a bit from them for sure, but I used to worry whether my style of pitching would work in modern baseball.”

As for the role model, he doesn’t necessarily have one, but seeing how Bradford and Watanabe had turned in nice careers in their own respective leagues, Park gained confidence. “It was like ‘Ah, they can survive in that high-level of a league,'” he said, “That was the point where I gained more confidence and dreamed bigger in succeeding in professional baseball.”

On his wunder curve:

Park’s main strength is his curveball. According to Statiz, a KBO sabermetrics website, his curveball led the entire league in its pitch value for both 2017 and 2018 (18.8 and 12.6 runs saved, respectively). Some may see it as a slider, but Park says that it’s a curveball. Here’s the grip:

Here’s how he releases it:

Here’s how he simulates the release and spin:

And here are the results:

Park said he practiced the curveball release by throwing it as far as possible on an open field. “I did it to make it ‘float,’” he said, “I’ve been practicing it since I was younger. I think a lot of it was about having a pride in being different than everyone else. So I just kept going like ‘Let me try again, again, again, again…’ and it has ended up how it looks now.”

Park also says that he makes it move differently for different-handed hitters. “I have better stats against left-handed hitters than right-handed hitters,” he notes, and he’s not really wrong. In 2018, he allowed a .714 OPS against lefties as opposed to .723 OPS against righties. From 2015 to 2019, he’s allowed .724 OPS against LHH and .775 OPS against RHH.

“I think a lot has to do with my curveball trajectory. Against the lefties, I like to float the ball straight up [think reverse 12-6 curveball] and against the righties, I throw with a tilt [reverse 11-5] tilt to it. I’m really curious how it would work out in different leagues, like the majors.”

Here’s a Park curve against a lefty:

…and a righty (admittedly, this looks similar to how he’d throw against a lefty):

Not only he can locate it high to induce whiffs, but also he can locate the pitch low. It can be effective because the pitch, which seems like it would end up lower than the zone, “rises” towards the end to nick the edge. Here’s one from this past postseason:

And here’s a three-pitch strikeout in which he used the curveball in similar locations to get a called strike, a weak foulball, and a swinging strike.

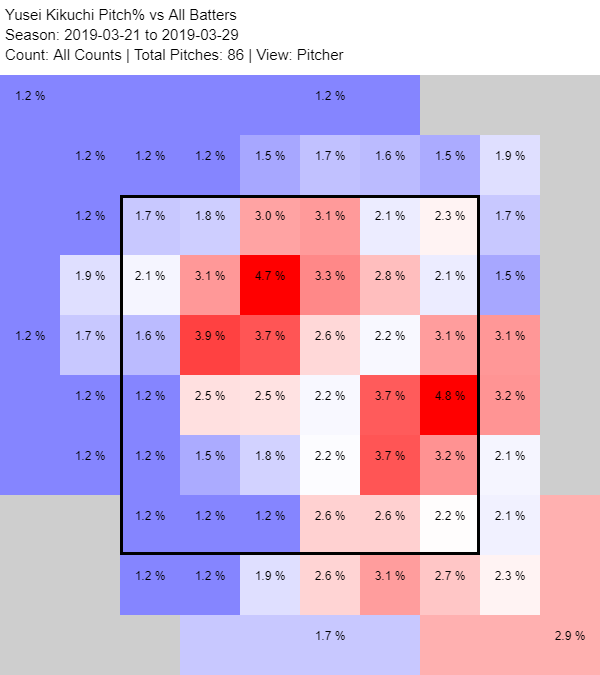

In 2018, he used the curveball 42.6% of the time, which is a significant amount. The pitch averaged at 119.1 kmph (74.0 mph). Park also has a fastball (41.1% usage), which averaged 131.6 kmph (81.8 mph), a two-seam fastball (12.2%) that averaged 128.5 kmph (79.9 mph) and a changeup that he used very sparingly (3.7%) that averaged 123.8 kmph (76.9 mph).

On his major league dreama:

Park doesn’t keep his desire to play in the majors a secret. He has been eager to prove that his style of pitching will work at the highest level of baseball. “I don’t know when it will happen,” Park said, “but if I do go to the majors, I want people to think ‘There’s a pitcher like this and he can really pitch in the majors.’ I hope I can help bring more attention to sidearm and submarine pitchers.”

Park says he also wants to join other Korean big leaguers. “If you’re a baseball player, MLB is the final frontier,” he said, “I’d love to join Korean guys like Hyun-Jin Ryu, Ji-Man Choi and Shin-Soo Choo. And I want my name, Park Jong-Hoon, to be known to the major league fans.”

According to a person familiar to the situation, several major league scouts have periodically come to Munhak Baseball Stadium to watch his starts. If the Wyverns were to post him as soon as he is eligible, the timing could be tricky. Depends on how long he is on the active roster and avoids injuries, he would be eligible as soon as after the 2020 season. If he is not as lucky with how his service time stacks up, it would be after 2021. Because Park will turn 30 in August 2021, one would assume that he wants to head stateside as soon as possible.

At this moment, it is a bit early to speculate on his major league chances. What helps Park is that he may not have completed developing due to his unusual amateur background, which could project well by the time he’s eligible to be posted. He also has brings the benefit of giving a very, very different look to hitters, not to mention that his approach has worked well in the offense-friendly environment of the KBO. There are, of course, many question marks. Heck, there are question marks for players who are deemed to be top-notch major league prospects. His command is still work in progress, we don’t know how well his stuff would translate in the majors, and we don’t know yet how interested the teams are.

Park wanted to be different, he learned to use his uniqueness in the KBO, and he became one of the best Korean-born starting pitchers in the league. That in itself is pretty significant.

*All KBO stats from Statiz unless specified.