On the public side, there are few opportunities to see the precise financial machinations of major league baseball teams. The Atlanta Braves are a publicly traded company so we have some information on their inner-workings. And a recent piece by Kevin Acee at the San Diego Union Tribune provides a little bit more information. Acee was granted access to some of the Padres’ finances, though as Acee noted, the league keeps a close watch on financial information and generally doesn’t want it to get out:

The caveat from the club was that many of the numbers shared herein had to be “general.” The Padres are a private company and one of 30 members of a greater private organization. One member does not have the prerogative to make public financial data Major League Baseball has not approved for release.

The Padres’ decision to grant a reporter access to some of the team’s financial information is an unusual one, though the motivation is fairly clear. The Padres are still in the midst of a rebuilding process that isn’t likely to end this season. The club believes their window of contention isn’t yet open and as a result, they aren’t likely to spend big right now. A peek into the books, and the team’s debt, helps them provide further justification for that lack of spending. There is a lot of financial information disclosed in the article, and it is probably best to break things down a bit.

The Debt

The crux of Acee’s article involves a refinancing of the debt the team’s current owners have carried since purchasing the Padres. According to the article, that debt amounted to roughly $193 million at the time of the purchase back in 2012 — it was no doubt factored into the purchase price — and the interest rate on the loans was something like 8.5%. Due to the nature of the loan, which included a make-whole provision that would require paying extra for paying down the loan early, refinancing it to get a lower interest rate would have meant an extra payment of close to $70 million. As a result, the team elected to make payments on the loan, including interest payments of $13 million in 2015 alone.

By 2017, the make-whole penalty was down to $28 million and the club made a cash call for about half of that amount and used some of their MLBAM money for the rest. Reading between the lines here, the piece mentions a total of $68 million in money coming from the sale of BAMTech, with $50 million of that amount presumed to have been received last year. That means that the first sale of MLBAM to Disney, which netted the league one billion dollars, likely resulted in some smaller payment, perhaps $18 million, that was used by the Padres in their refinancing in 2017. The team appears to have further used about $45 million of the $50 million BAMTech proceeds to pay down additional debt. The club has now paid down 40% of the original $193 million, reducing interest payments to around $4 million, a savings of around $8 million per year, plus additional savings on principal payments. In short, the club took $15 million of owner money. plus nearly all the BAMTech money it received, and used it to make $10 million or more per year for the foreseeable future. It has obviously been a good investment for the owners, and the tenor of the article suggests that that money will be invested back into the club at some point in the future, likely, if team officials are to be believed, when the club is closer to contention.

The Minors

In 2016, the Padres were coming off a minor debacle in 2015 (more on that in a bit), having expended a decent amount of cash and prospect capital to attempt to contend. That attempt failed, and the Padres decided not to invest any more money in the major league ball club. Under baseball’s old international spending rules, teams could splurge on international prospects for a year before being restricted to more expenditures in the following two seasons. The Padres splurged like nobody had splurged before, spending around $40 million on prospects and around that amount on penalties. Between the major league payroll and the bonuses for the draft and international amateurs (and the penalties that followed), the team probably spent close to $200 million in 2016, with Acee’s piece indicating the owners pitched in about $20 million to make that happen.

As for the results, the Padres now have one of the best farm systems in baseball, and that 2016 class is a big reason for their success. As of the end of last season, the Padres had 12 players from that class alone receive a graded rank, including three who already project as average despite the fact that most of these players are under 20 years old. Those 12 prospects, including Adrian Morejon, Luis Patino, and Michael Baez, were already worth roughly $100 million by the end of last year. While it hasn’t impacted the results at the major league level yet, that investment should pay huge dividends going forward. As for investments that didn’t go so well…

The First Prellering

The Padres hired A.J. Preller in the middle of the 2014 season, and Preller aimed to make the team a contender the following year. He essentially traded Yasmani Grandal for Matt Kemp, then sent prospects to Atlanta for Justin Upton. He traded Joe Ross and Trea Turner, among others, for Wil Myers and others. James Shields was given a four-year contract. Right before the season started, he took on the money owed to B.J. Upton to get Craig Kimbrel. Those deals added about $20 million in payroll over the previous year and about $40 million over the 2013 campaign. The moves weren’t successful, although they weren’t quite the disaster the Union-Tribune piece and Padres ownership make them to be.

In the piece, the club claimed to have spent $40 million more for the season. That is partially true given they spent that much in new salaries, but when compared to the previous season, the additions were about half that much. Interestingly, the club indicated that all that movement netted the team an extra $15 million in ticket sales and concessions. While that number isn’t too far off from the payroll increase, we can glean more from that bit of information. From 2014 to 2015, the Padres increased attendance by 265,000 fans. Some simple math has the increase in revenue at about $57 per attendee. What’s interesting about that information is just how the attendance increase happened. The Padres’ gambit almost worked.

On June 13, the Padres had a .500 record, were five games out of first place, and three games out of the wild card. Over the next month, they went 9-17 and fell out of the playoff race. Through the trade deadline that season, the club was averaging 31,782 fans, but after the season went south, attendance the rest of the way dropped to 28,200. If the team had remained competitive and drawn the same amount, that potentially would have meant another $6.5 million in revenue, making the increase in payroll worth it. If the team had made the playoffs, the club would have come out ahead. Adding the declining Kemp, the unproven Myers, a one-inning closer in Kimbrel, and getting a below-average performance from Shields sunk the club in 2015, but the decision to go for it wasn’t necessarily bad; it just turned out that some of the players underperformed or were poor fits on the roster. And the added salary commitments ensured the team would spend millions on players who wouldn’t even be with the team after another season. Preller’s first go at building a contender failed; the second, as noted, had to take a different approach.

Revenue Estimates

The article doesn’t come out and say how much the Padres make, but there are a fair number of estimates. First, the piece says that interest payments went from 5% ($12.6 million in 2015) to 2% ($4.6 million in 2018) of the budget, which would put revenues somewhere between $252 million and $230 million, though a few decimal points of difference on the interest percentage significantly changes the total. Looking at their larger expenditures and the percentage of expenses might be more helpful. Roughly one-third of revenues have gone to major league salaries over the last four years, which would put average annual revenue at around $295 million. They have spent around 22% of revenue on operating expenses — that number is listed at $68 million, which would put revenues at around $310 million. Forbes last year estimated the Padres’ revenue at $266 million, which now looks like that might be a little low. I should also note that the team does spend money on stadium maintenance and improvements along with all those debt repayments, but that those amounts are taken out of net local revenue and serve to increase the amount of revenue sharing they receive from the league.

Looking Ahead

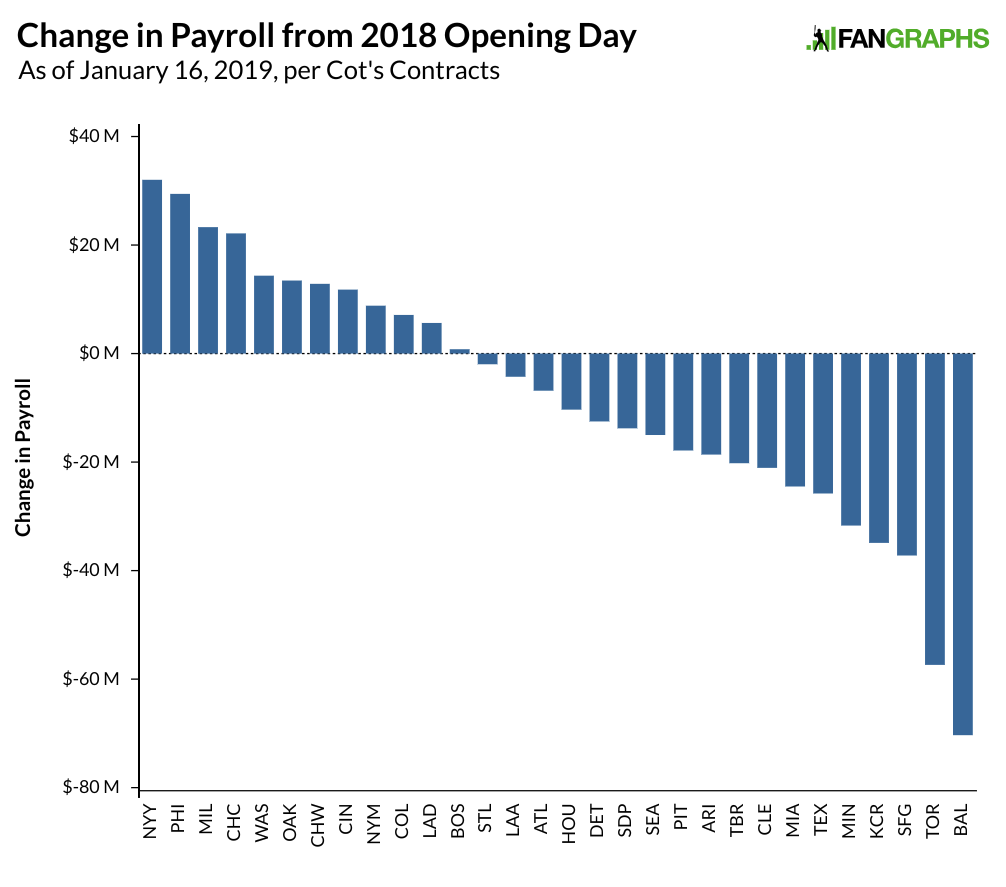

Acee’s whole piece is fascinating, and I recommend reading it in full. All of baseball has seen a considerable increase in revenue over the last few seasons, an increase from which the Padres have benefited. With their revenues, they have opted to pay down debt and make an international splash. Their payroll has been lower due to those decisions, and the amount of payroll we actually see on the field has been lower still, due to bad contracts taken on in trades and free agent signings for players who were later dealt with money attached. The explanation offered in the piece is pretty clear, and while the team wasn’t completely forthcoming, most of the information checks out. The team is asking fans to be patient for one more year. Building up the minor league system should eventually create a better on-field product at Petco, but the team’s debt reduction and refinancing does more to add to a franchise value that has already doubled since Executive Chairman Ron Fowler’s group took over seven years ago. The club will need to continue to invest in the big league product to demonstrate that this is more than just perpetually shifting fans’ expectations off into the future. It’s up to the fans to determine how much more losing they can stomach.