The Dodgers have an injury-prone lefty who’s been dominating hitters lately, and it’s not Clayton Kershaw. Nor is it Rich Hill — it’s Hyun-Jin Ryu. The 32-year-old South Korea-born southpaw has yet to allow more than two runs in any of his eight starts (one of which, admittedly, was curtailed by a groin strain), and lately, he’s been utterly stifling. On May 1, he threw eight innings of four-hit one-run ball against the Giants. On May 7, he threw a four-hit shutout of the Braves. On Sunday in Los Angeles, he no-hit the Nationals for 7.1 innings before Gerardo Parra — who on Saturday night hit a game-winning grand slam — clubbed a ground-rule double that proved to be the Nationals’ only hit of the day.

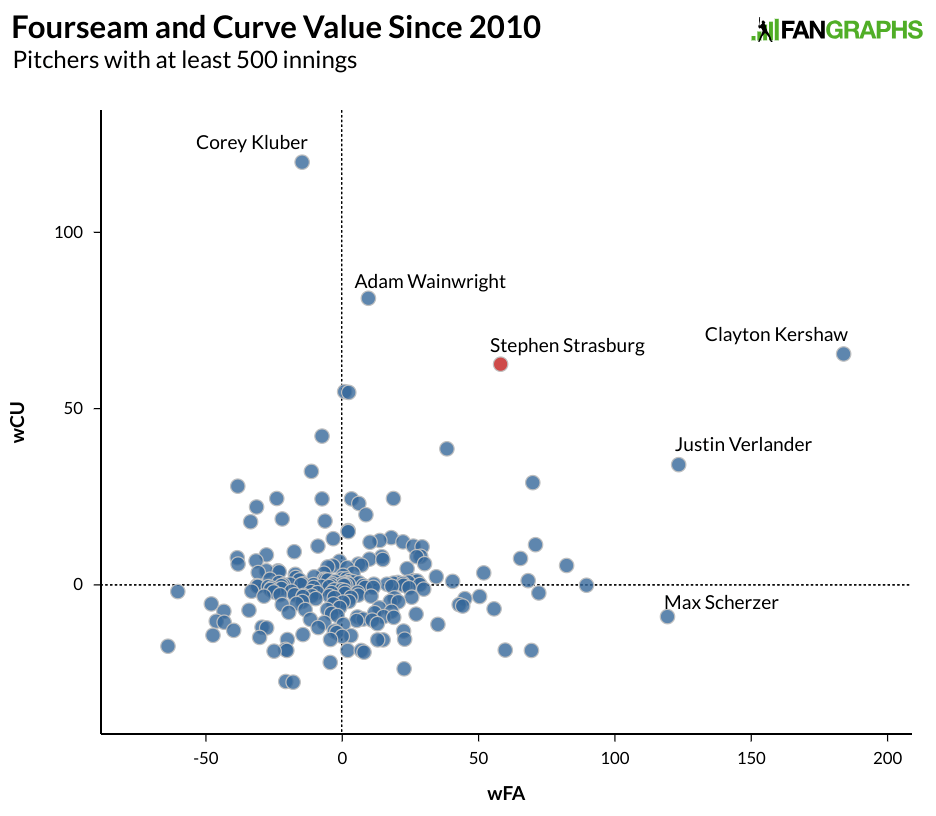

Here’s some good company:

Though Ryu wasn’t as efficient as in his previous turn, where his 93-pitch outing gave him the season’s second Maddux, after Kyle Hendricks‘ 81-pitch job on May 3, he had allowed only one baserunner to the point of Parra’s hit, via a fourth-inning walk issued to former teammate Brian Dozier. He had served up just two hard-hit balls, a 99.1 lineout off the bat of Kurt Suzuki in the second inning, and a 95.5 mph fly ball from Anthony Rendon in the fourth, and had been the beneficiary of every no-hit bid’s seemingly obligatory defensive gem. In the sixth inning, Stephen Strasburg appeared to have singled to right field… only to be thrown out at first base by right fielder Cody Bellinger (it’s just after the one-minute mark here):

Alas, the lefty-hitting Parra, who earlier this month drew his release by the Giants and entered the day hitting an anemic .194/.276/.290, sliced a 98.0 mph drive to the warning track in left centerfield, where it bounced over the wall for the Nationals’ first and only hit of the day. That was Ryu’s 105th pitch of the afternoon; he completed the frame having thrown 116 pitches, the highest total of his MLB career.

Completing the no-hitter had seemed like an unlikely proposition; Ryu had finished the seventh inning at 98 pitches. Given the 24 pitches he burned in the fourth (including eight on Adam Eaton’s leadoff groundout), he appeared hellbent on testing the length of manager Dave Roberts‘ leash. Since taking the reins of the Dodgers for the 2016 season, Roberts has been at the forefront of a growing trend of pulling pitchers with no-hitters in progress (forget the openers, we’re talking those of at least five innings). His total of three in that span is tied with the Marlins’ Don Mattingly for the MLB high. Roberts famously gave the hook to Ross Stripling after 7.1 no-hit innings on April 8, 2016, then removed Hill after seven perfect innings on September 10 of that season, and told Walker Buehler to hit the showers on May 4 of last season; three relievers helped the rookie finish the job.

What’s more, Ryu had never thrown more than 114 pitches in a stateside start, and had been above 105 only twice in the past three seasons: 108 pitches against the Padres on August 12, 2017, and 107 pitches in the aforementioned May 1 start. “I’m not sure there’s a pitcher/manager combo alive less likely to push him through 9 just to try for a no hitter,” tweeted MLB.com’s Mike Petriello. Roberts suggested that he would have been more flexible…

…which was easy to say in hindsight, but anyway, enough about the manager. The pitcher struck out nine to go with his one walk and one hit, generating 14 swings and misses, including seven via his changeup and four via his cutter. In doing so, he lowered his ERA to 1.72, second in the NL; he’s tied for third in FIP (2.71), and ranks fifth in WAR (1.5). Most impressive within his stat line is his 54-to-3 strikeout-to-walk ratio in 52.1 innings. That’s a 28.6% strikeout rate (eighth in the NL) and a league-low 1.6% walk rate; his 27.0% K-BB% is third.

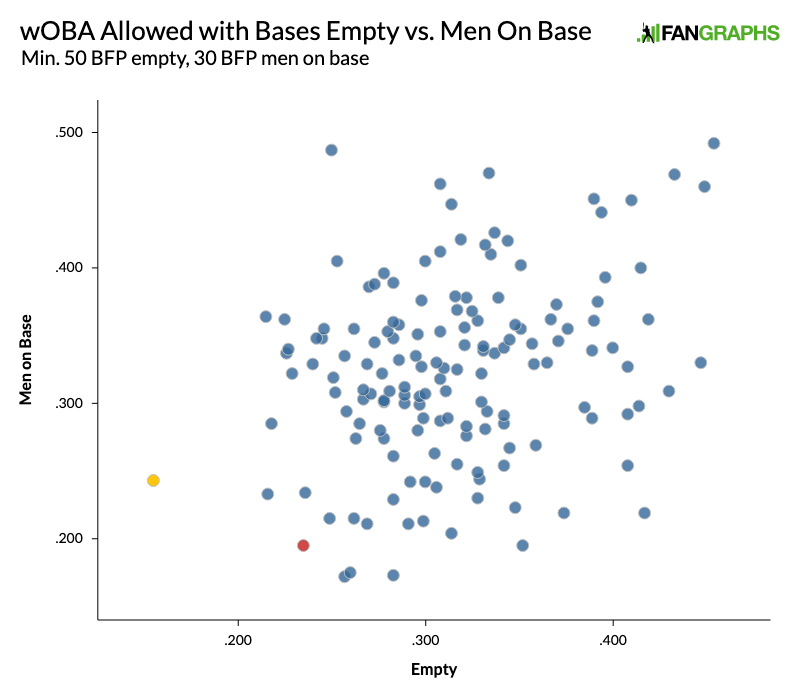

Combine that stingy walk rate with a .230 BABIP (second in the league, thanks in large part to the Dodgers’ stellar defense thus far) and you’ve got a pitcher who rarely has anybody on base. I haven’t played fantasy baseball in nearly a decade, so I seldom look at stats like WHIP or strand rate for even casual purposes, but dig: his 0.726 WHIP is second in the majors behind only Chris Paddack (0.689), while his 94.6% strand rate is in a virtual tie with Justin Verlander for the highest mark of the post-strike era. Blake Snell (88.0% last year) and Kershaw (87.8% in 2017) own the highest marks among full-season ERA qualifiers, while Pedro Martinez (86.0% in 2000) and Zack Greinke (86.5% in 2015) are tops among those who reached 200 innings.

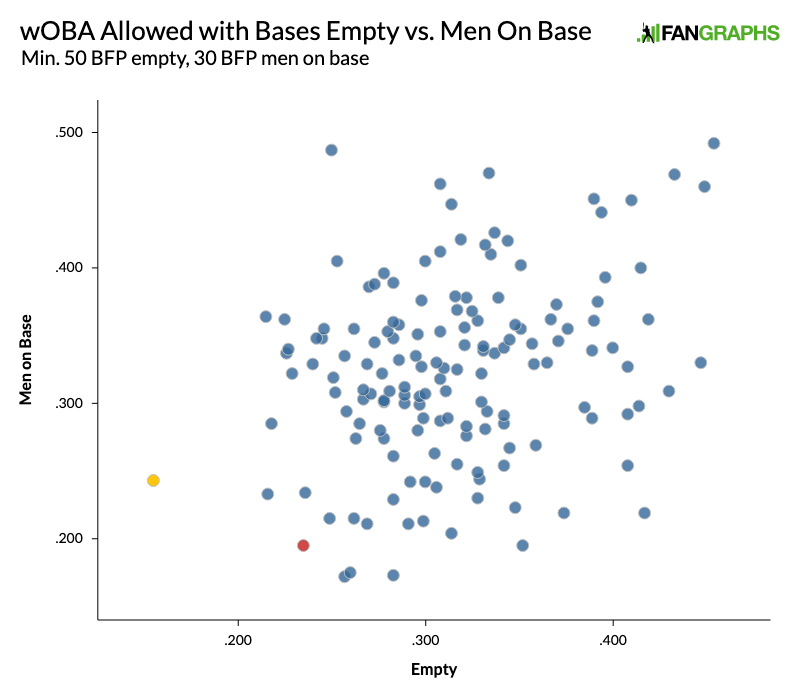

Putting this in more analytical terms, albeit with the usual sample size caveats, here’s a scatter plot of pitcher performance (wOBA allowed) with the bases empty versus when men are on base:

Ryu is the red dot, Paddack the yellow one (the Padres righty is one of the reasons I had to lower the threshold of batters faced with men on base).

This is actually the second season in a row that Ryu has ranked among the majors’ stingiest pitchers. Last year, in 15 starts, he posted a 1.97 ERA and 3.00 FIP, with a 27.5 % strikeout rate and 4.6% walk rate. He missed 3.5 months due to a left groin strain so severe its description included the cringe-inducing phrase “tore muscle off the bone,” but he did not require surgery. That was just the latest in a string of injuries that has dogged the burly lefty since coming over from Korea, most notably a torn labrum that cost him all of 2015 and the first half of ’16, then elbow woes that culminated in debridement surgery after he made just one start in the latter season. Only in his 2013 rookie season did he make 30 starts or qualify for the ERA title, yet he owns a career 3.11 ERA and 3.36 FIP. Among the 112 pitchers with at least 600 innings in that span, his 82 ERA- ranks 17th, his 85 FIP- 18th, but because of his less-than-perfect attendance, he’s a modest 47th in WAR (11.9).

Ryu doesn’t have exceptional velocity; per Statcast, his four-seamer’s 90.4 mph average velo ranks in the 11th percentile as does his fastball spin. He’s in the middle of the pack as far as exit velocity (87.7 mph) and hard hit rate (38.8%) are concerned too. His 11.7% swinging strike rate is in the 66th percentile, though his 34.5% chase rate is in the 81st percentile. As The Athletic’s Eno Sarris pointed out last week, he’s the rare pitcher who has above-average command of five different pitches according to Stats LLC’s new Command+ metric, along with Marco Gonzales, Merrill Kelly, Mike Leake (who has six such pitches), Max Scherzer, and Noah Syndergaard; for Ryu, that would be his four-seamer, sinker, cutter, changeup, and curve. Obviously, that group includes a couple of impressive names, but it’s nonetheless a mixed bag, and only tells us so much.

The exceptional results Ryu has been getting owe a considerable debt to his changeup and cutter. The former, which he throws 22.0% of the time, averages just 79.1 mph according to Pitch Info, giving him more than 10 mph of separation from the, uh, heater. It falls out of the zone more often than not, batters can’t resist chasing it, and when they make contact, they tend to hit it on the ground. His results are more or less on par with the two young changeup artists I covered last week, Luis Castillo and Chris Paddack; he allows fewer baserunners with the pitch thanks to the low walk rate, but gets hit a little harder:

Some Damn Good Changeups

| Pitcher |

PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

wOBA |

xwOBA |

EV |

GB% |

O-Swing% |

Zone% |

SwStr% |

| Ryu 2018 |

65 |

.177 |

.203 |

.274 |

.194 |

.229 |

79.9 |

37.2% |

49.3% |

34.8% |

23.0% |

| Ryu 2019 |

60 |

.121 |

.133 |

.207 |

.146 |

.251 |

83.1 |

55.8% |

56.4% |

39.5% |

20.4% |

| Castillo |

85 |

.110 |

.190 |

.121 |

.152 |

.141 |

80.8 |

68.6% |

54.2% |

24.4% |

31.1% |

| Paddack |

63 |

.138 |

.206 |

.155 |

.172 |

.219 |

83.5 |

66.7% |

51.2% |

36.6% |

21.3% |

SOURCE: Brooks Baseball, Baseball Savant

wOBA, xwOBA and EV via Baseball Savant, all other stats via Pitch Info.

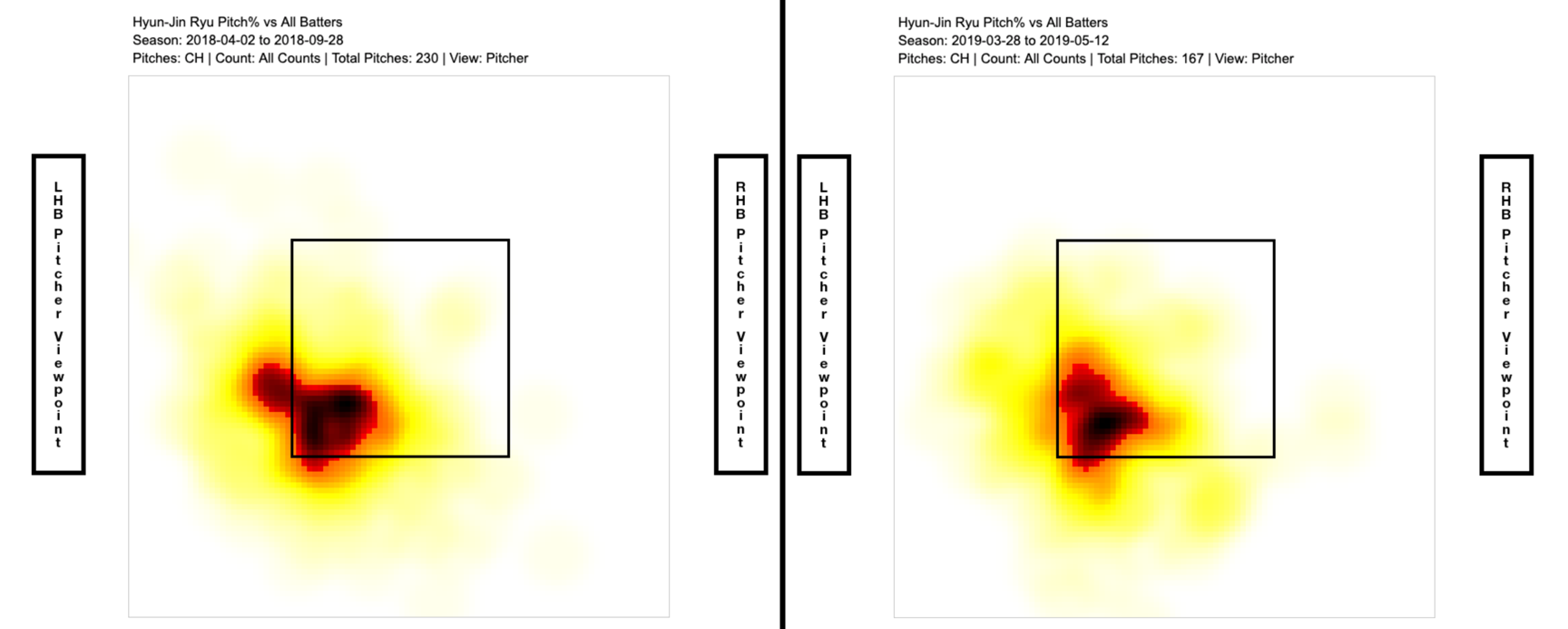

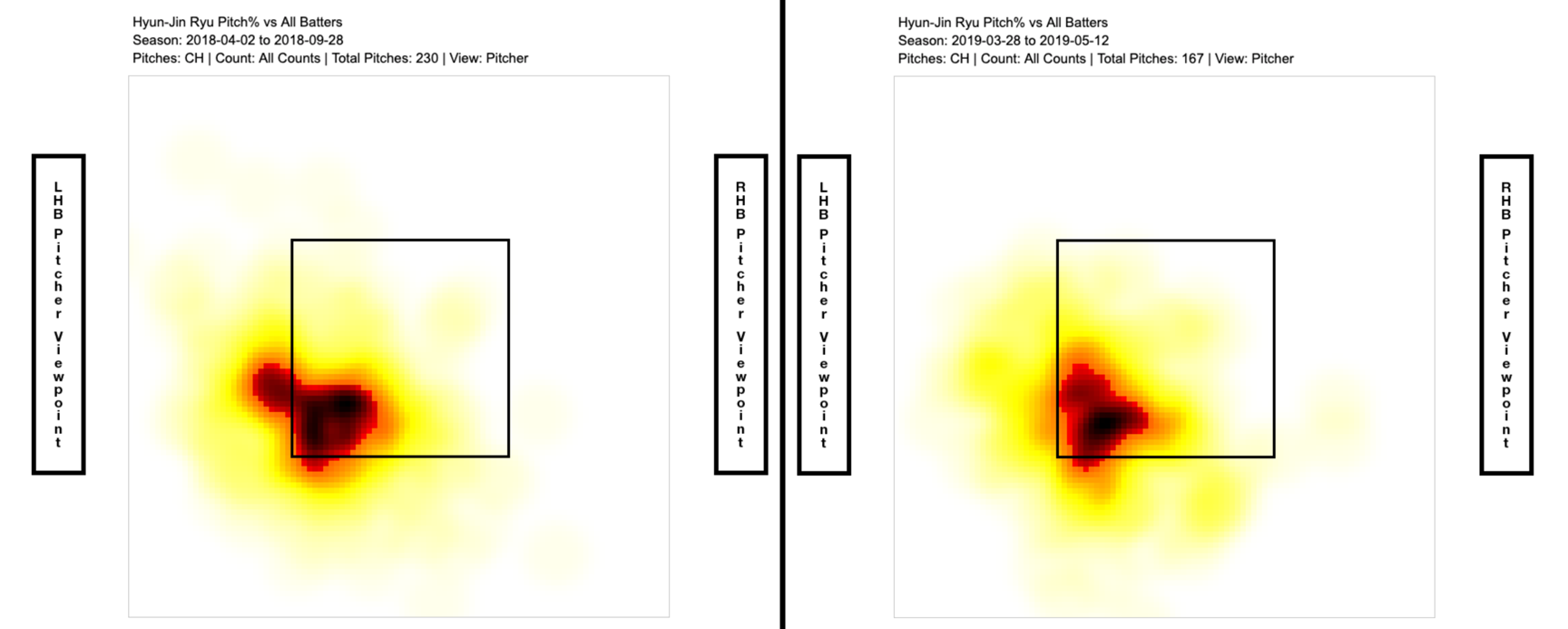

I’ve included Ryu’s 2018 numbers there to illustrate that the pitch is working even better for him than it did last year, when it worked pretty well. The big differences from then to now are last year’s lower groundball rate and tendency to work further off the plate against righties (and in to lefties):

Petriello has a good look at how the vertical gap between Ryu’s four-seamer and his changeup has widened this year, though that’s mostly due to his working higher with the heater. As for the cutter, it’s a pitch Ryu didn’t introduce into his arsenal until 2017. It’s about three clicks slower than the fastball, averaging 87.3 mph, and it now accounts for 21.2% of his pitches thrown; over that three-year timespan, he’s mothballed his slider and cut way back on the usage of his curve. The pitch didn’t work especially well for him last year:

Hyun-Jin Ryu’s Cutter

| Year |

PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

wOBA |

xwOBA |

EV |

GB% |

O-Swing% |

Zone% |

SwStr% |

| 2017 |

108 |

.232 |

.324 |

.326 |

.272 |

.282 |

83.3 |

58.1% |

27.2% |

48.7% |

6.3% |

| 2018 |

87 |

.274 |

.299 |

.452 |

.318 |

.322 |

88.1 |

52.4% |

23.9% |

55.1% |

6.8% |

| 2019 |

41 |

.150 |

.171 |

.275 |

.192 |

.248 |

91.8 |

56.0% |

29.1% |

47.7% |

15.2% |

SOURCE: Brooks Baseball, Baseball Savant

wOBA, xwOBA and EV via Baseball Savant, all other stats via Pitch Info.

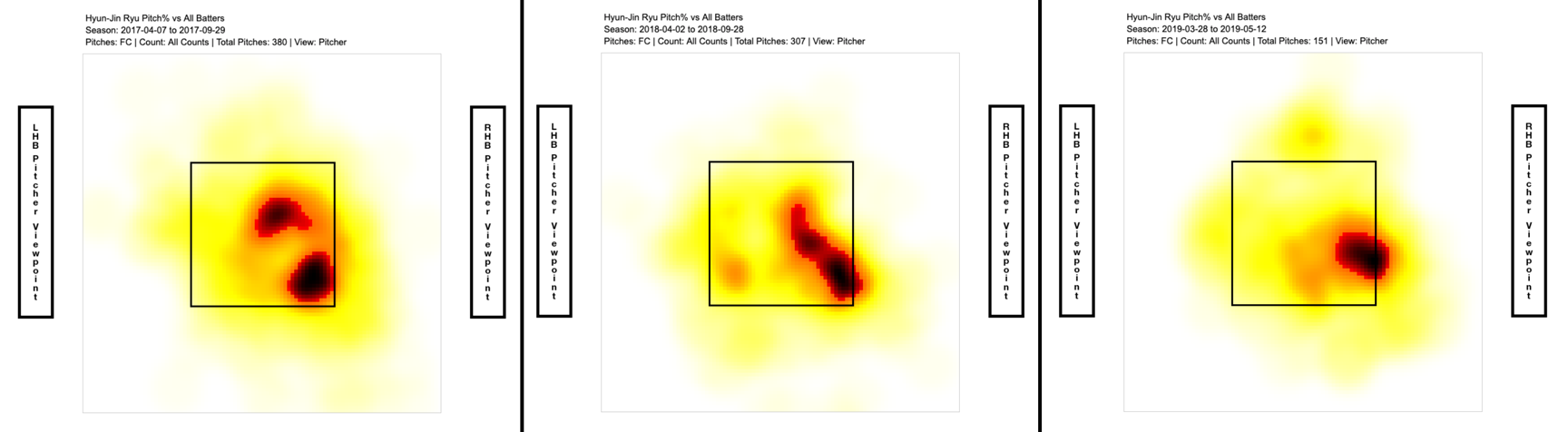

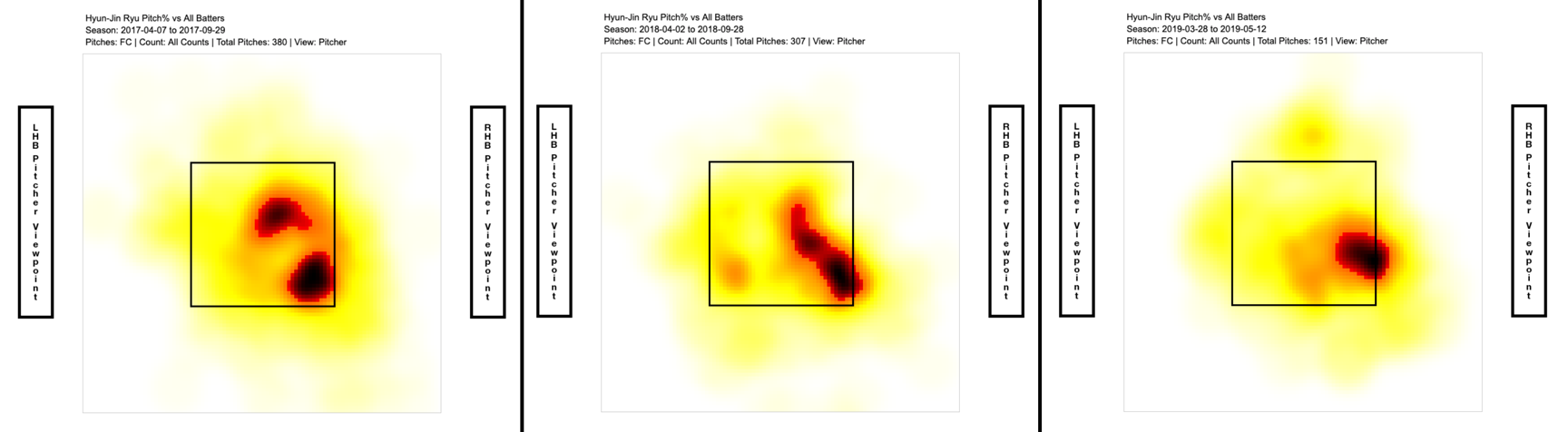

Look at that jump in swinging strike rate! I don’t see a great deal of year-to-year variation in his spin rate (2029 to 2063 rpm in that span) or movement to account for the jump, but location-wise, he’s not only throwing it in the zone less often (while getting significantly more chases), he’s keeping it out of the middle third:

Obviously, the caveat all over this is that of small sample size; we are talking about a body of work that covers a modest 134.2 innings over the past two seasons. Still, it’s been an impressive run, and if Ryu — who returned to the Dodgers upon completion of his six-year, $36 million deal by accepting a $17.9 million qualifying offer — can stay upright while fleshing out this body of work, he should be in line for some kind of multiyear payday this coming winter, though one with some complexity of structure likely — incentives, a vesting option or a club option. J.A. Happ’s two-year, $34 million deal with a $17 million vesting option for year three comes to mind.

While Ryu’s fragility makes him one more pitcher in a rotation full of less-than-durable ones, his early-season performance has provided a best-case scenario while helping the Dodgers weather the late arrivals of Kershaw and Hill, whose combined total of eight starts matches his own. His rise to the occasion is just one more reason why the Dodgers (27-16) are vying for the league’s best record and remain the favorites for a third straight NL pennant.