Introducing the Kirby Index: A New Way to Quantify Command

In the course of researching the haphazard nature of JP Sears’ fastball command for my blog Pitch Plots, I realized I was missing the answer to a fundamental question: Why does the ball go where it goes?

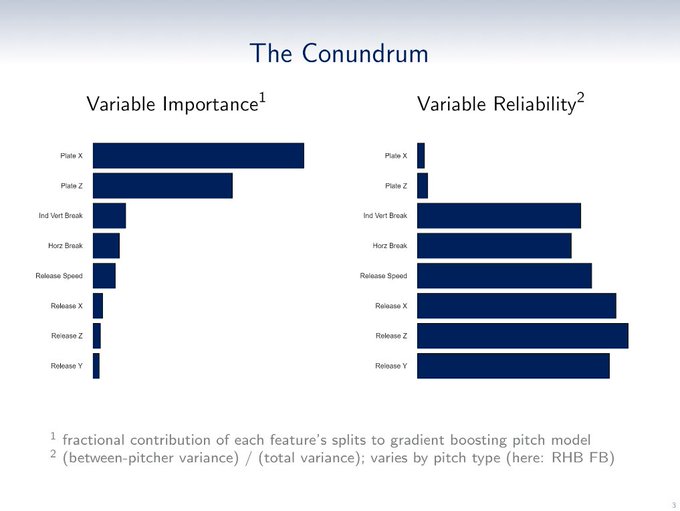

Specifically, I had no idea which variables determine the physical location where a pitch crosses home plate. My first guesses revealed nothing: a combination of velocity, extension, spin, and release height had no relationship to a pitch’s eventual location. If it wasn’t any of these factors, what could Sears change to throw his fastball to better locations?

I was missing the key variable: the release trajectory. Trajectory, as defined here, is not just release height and width but also the vertical and horizontal release angles of the pitch, which are not widely available to the public on a pitch-by-pitch basis.

The release trajectory, it turns out, explains nearly everything about the ultimate location of a pitch. Read the rest of this entry »