9/28 Late Morning Update

ZiPS Playoff Drive Projections – AL Wild Cards

| Day |

Home Team |

Starter |

Road Team |

Road Starter |

Home Team Wins |

Road Team Wins |

| 9/28 |

Orioles |

Bruce Zimmermann |

Red Sox |

Chris Sale |

37.5% |

62.5% |

| 9/28 |

Blue Jays |

Hyun Jin Ryu |

Yankees |

Jameson Taillon |

56.1% |

43.9% |

| 9/28 |

Mariners |

Tyler Anderson |

Athletics |

Chris Bassitt |

41.1% |

58.9% |

| 9/29 |

Orioles |

Zac Lowther |

Red Sox |

Nathan Eovaldi |

31.6% |

68.4% |

| 9/29 |

Blue Jays |

José Berríos |

Yankees |

Gerrit Cole |

51.9% |

48.1% |

| 9/29 |

Mariners |

Logan Gilbert |

Athletics |

Frankie Montas |

45.0% |

55.0% |

| 9/30 |

Orioles |

Alexander Wells |

Red Sox |

Nick Pivetta |

31.4% |

68.6% |

| 9/30 |

Blue Jays |

Robbie Ray |

Yankees |

Corey Kluber |

56.9% |

43.1% |

| 10/1 |

Blue Jays |

Alek Manoah |

Orioles |

Chris Ellis |

74.5% |

25.5% |

| 10/1 |

Nationals |

Erick Fedde |

Red Sox |

Eduardo Rodriguez |

47.3% |

52.7% |

| 10/1 |

Yankees |

Nestor Cortés Jr. |

Rays |

Luis Patino |

54.3% |

45.7% |

| 10/1 |

Mariners |

Marco Gonzales |

Angels |

Jose Suarez |

46.2% |

53.8% |

| 10/1 |

Astros |

Zack Greinke |

Athletics |

Sean Manaea |

57.0% |

43.0% |

| 10/2 |

Blue Jays |

Steven Matz |

Orioles |

John Means |

62.7% |

37.3% |

| 10/2 |

Nationals |

Josh Rogers |

Red Sox |

Tanner Houck |

38.8% |

61.2% |

| 10/2 |

Yankees |

Jordan Montgomery |

Rays |

Shane McClanahan |

53.7% |

46.3% |

| 10/2 |

Mariners |

Chris Flexen |

Angels |

Jhonathan Diaz |

50.7% |

49.3% |

| 10/2 |

Astros |

Framber Valdez |

Athletics |

Paul Blackburn |

64.7% |

35.3% |

| 10/3 |

Blue Jays |

Hyun Jin Ryu |

Orioles |

Bruce Zimmermann |

66.0% |

34.0% |

| 10/3 |

Nationals |

Josiah Gray |

Red Sox |

Chris Sale |

41.6% |

58.4% |

| 10/3 |

Yankees |

Jameson Taillon |

Rays |

Shane Baz |

45.3% |

54.7% |

| 10/3 |

Mariners |

Tyler Anderson |

Angels |

Shohei Ohtani |

38.4% |

61.6% |

| 10/3 |

Astros |

Jake Odorizzi |

Athletics |

Cole Irvin |

63.5% |

36.5% |

ZiPS Playoff Drive Projections – AL Wild Card Standings

| Team |

Wild Card 1 |

Wild Card 2 |

Playoffs |

| Boston |

37.2% |

42.1% |

79.3% |

| New York |

46.0% |

29.4% |

75.3% |

| Toronto |

16.0% |

24.1% |

40.2% |

| Seattle |

0.8% |

4.3% |

5.2% |

| Oakland |

0.0% |

0.1% |

0.1% |

`

ZiPS Playoff Drive Projections – Changes in Playoff Projections

| Scenario |

BOS |

NYA |

TOR |

SEA |

OAK |

| Boston Beats Washington on Friday |

9.3% |

-2.8% |

-5.0% |

-1.4% |

0.0% |

| Boston Beats Washington on Sunday |

8.3% |

-2.6% |

-4.3% |

-1.3% |

-0.1% |

| Boston Beats Washington on Saturday |

7.6% |

-2.4% |

-3.9% |

-1.3% |

0.0% |

| Boston Beats Baltimore on Tuesday |

7.6% |

-2.3% |

-3.9% |

-1.4% |

0.0% |

| Baltimore Beats Toronto on Friday |

7.1% |

7.0% |

-15.9% |

1.8% |

0.0% |

| Boston Beats Baltimore on Thursday |

6.8% |

-2.0% |

-3.6% |

-1.1% |

-0.1% |

| Baltimore Beats Toronto on Sunday |

6.7% |

6.4% |

-14.6% |

1.5% |

0.0% |

| Boston Beats Baltimore on Wednesday |

6.6% |

-2.1% |

-3.4% |

-1.1% |

0.0% |

| Baltimore Beats Toronto on Saturday |

6.4% |

6.2% |

-14.2% |

1.6% |

0.0% |

| New York Beats Toronto on Tuesday |

3.5% |

15.3% |

-19.1% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

| Tampa Bay Beats New York on Friday |

3.5% |

-9.6% |

5.0% |

1.1% |

0.0% |

| Tampa Bay Beats New York on Saturday |

3.4% |

-9.6% |

5.0% |

1.2% |

0.0% |

| New York Beats Toronto on Thursday |

3.2% |

15.3% |

-18.8% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

| New York Beats Toronto on Wednesday |

2.9% |

14.6% |

-17.9% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

| Tampa Bay Beats New York on Sunday |

2.8% |

-7.6% |

4.0% |

0.8% |

0.0% |

| Los Angeles Beats Seattle on Saturday |

1.6% |

0.9% |

1.1% |

-3.6% |

0.0% |

| Los Angeles Beats Seattle on Sunday |

1.5% |

0.8% |

1.1% |

-3.3% |

0.0% |

| Los Angeles Beats Seattle on Friday |

1.5% |

0.8% |

1.2% |

-3.5% |

0.0% |

| Oakland Beats Seattle on Wednesday |

1.3% |

0.8% |

1.1% |

-3.3% |

0.1% |

| Oakland Beats Seattle on Tuesday |

1.2% |

0.9% |

1.0% |

-3.2% |

0.1% |

| Houston Beats Oakland on Friday |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

-0.1% |

| Houston Beats Oakland on Saturday |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

-0.1% |

| Houston Beats Oakland on Sunday |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Oakland Beats Houston on Friday |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.1% |

| Oakland Beats Houston on Saturday |

0.0% |

0.0% |

-0.1% |

0.0% |

0.1% |

| Oakland Beats Houston on Sunday |

-0.1% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.1% |

| Seattle Beats Los Angeles on Saturday |

-1.7% |

-0.9% |

-0.9% |

3.5% |

0.0% |

| Seattle Beats Oakland on Wednesday |

-1.9% |

-1.2% |

-1.3% |

4.4% |

0.0% |

| Seattle Beats Los Angeles on Friday |

-2.0% |

-1.0% |

-1.1% |

4.1% |

0.0% |

| Toronto Beats New York on Tuesday |

-2.2% |

-11.6% |

14.0% |

-0.2% |

0.0% |

| Seattle Beats Oakland on Tuesday |

-2.2% |

-1.2% |

-1.5% |

4.9% |

-0.1% |

| Toronto Beats New York on Thursday |

-2.3% |

-11.7% |

14.1% |

-0.2% |

0.0% |

| Toronto Beats Baltimore on Friday |

-2.4% |

-2.4% |

5.3% |

-0.5% |

0.0% |

| Seatle Beats Los Angeles on Sunday |

-2.4% |

-1.5% |

-1.6% |

5.5% |

0.0% |

| Toronto Beats New York on Wednesday |

-2.6% |

-13.1% |

16.1% |

-0.3% |

0.0% |

| New York Beats Tampa Bay on Saturday |

-2.6% |

8.4% |

-4.6% |

-1.1% |

0.0% |

| New York Beats Tampa Bay on Friday |

-2.8% |

8.6% |

-4.8% |

-1.0% |

0.0% |

| New York Beats Tampa Bay on Sunday |

-3.1% |

9.2% |

-5.0% |

-1.0% |

0.0% |

| Toronto Beats Baltimore on Sunday |

-3.4% |

-3.1% |

7.3% |

-0.8% |

0.0% |

| Toronto Beats Baltimore on Saturday |

-3.5% |

-3.6% |

8.1% |

-1.0% |

0.0% |

| Washington Beats Boston on Friday |

-10.4% |

3.1% |

5.4% |

1.9% |

0.0% |

| Washington Beats Boston on Sunday |

-11.6% |

3.4% |

6.0% |

2.1% |

0.1% |

| Washington Beats Boston on Saturday |

-12.5% |

3.6% |

6.5% |

2.3% |

0.1% |

| Baltimore Beats Boston On Tuesday |

-12.8% |

3.8% |

6.6% |

2.5% |

0.0% |

| Baltimore Beats Boston on Thursday |

-14.6% |

4.3% |

7.5% |

2.7% |

0.1% |

| Baltimore Beats Boston on Wednesday |

-14.8% |

4.3% |

7.6% |

2.9% |

0.0% |

ZiPS Playoff Drive Projections – Game Leverage

| Game |

Leverage |

| Toronto vs. New York on Wednesday |

0.34 |

| Toronto vs. New York on Tuesday |

0.33 |

| Toronto vs. New York on Thursday |

0.33 |

| Toronto vs. Baltimore on Saturday |

0.22 |

| Toronto vs. Baltimore on Sunday |

0.22 |

| Baltimore vs. Boston on Wednesday |

0.21 |

| Baltimore vs. Boston on Thursday |

0.21 |

| Toronto vs. Baltimore on Friday |

0.21 |

| Baltimore vs. Boston On Tuesday |

0.20 |

| Washington vs. Boston on Saturday |

0.20 |

| Washington vs. Boston on Sunday |

0.20 |

| Washington vs. Boston on Friday |

0.20 |

| New York vs. Tampa Bay on Friday |

0.18 |

| New York vs. Tampa Bay on Saturday |

0.18 |

| New York vs. Tampa Bay on Sunday |

0.17 |

| Seatle vs. Los Angeles on Sunday |

0.09 |

| Seattle vs. Oakland on Tuesday |

0.08 |

| Seattle vs. Oakland on Wednesday |

0.08 |

| Seattle vs. Los Angeles on Friday |

0.08 |

| Seattle vs. Los Angeles on Saturday |

0.07 |

| Houston vs. Oakland on Saturday |

0.00 |

| Houston vs. Oakland on Sunday |

0.00 |

| Houston vs. Oakland on Friday |

0.00 |

The original data and methodology are below.

==

We’ve reached the final week of the 2021 regular season, and for fans of high-intensity, stretch-drive baseball — a group I think we can refer to as “everyone” — there’s still quite a lot to play for. Only five of the 10 playoff spots are claimed, with two of those five teams in a battle for a division title. And since there are just a handful of games left to play, we can move the ZiPS projections from the macro to the micro. In April, it’s always hard to project specific pitcher matchups, but with a week left to go in the season, it’s a more reasonable task of extrapolation. As a result, that allows me to adapt the ZiPS model into a game-by-game projection of the final week of the season for the relevant teams.

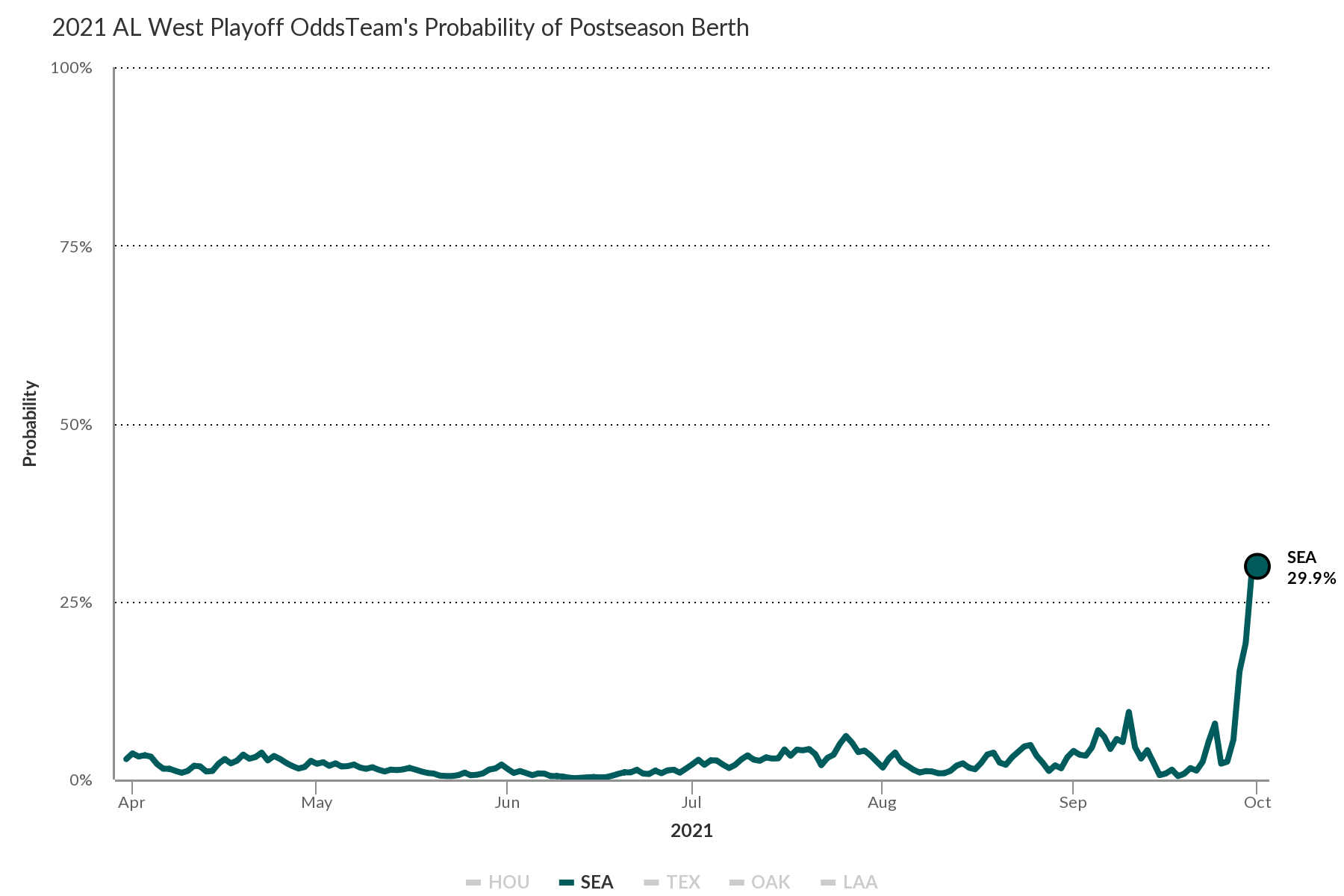

I’ve focused on three of the playoff spots, the two AL wild cards, and the NL East, along with the division versus wild card battle in the NL West. The Astros can still technically lose the division to the Mariners (one-in-about-1,800) or the Athletics (one-in-about-2,150), and the Cardinals could still have an epic collapse in which they lose six, the Reds win six, and they lose the tiebreaker (one-in-about-3,300). These could also become mathematical impossibilities quickly; if they become plausible rather than proverbial lottery tickets, I’ll update with the data.

Let’s start with the easy races.

NL East

The Braves enter the final week with a 2 1/2-game lead in the division but three games remaining against the Phillies. Their schedules are similar in strength, with Atlanta getting home games and Philadelphia on the road, something that’s largely canceled out by the former getting the slightly harder opponent (the Mets versus the Marlins). The edge comes from the cushion.

ZiPS Playoff Drive Projections – NL East

With the edge in the standings, ZiPS projects just over a four-in-five chance that the Braves will not have to play the Rockies in a makeup game on Monday. Overall, the Braves win the division 87.7% of the time without the makeup game, and the Phillies stick the Braves in at least a 1 1/2-game hole 1.0% of the time.

Read the rest of this entry »