Andy Pages Is a Perfect Fit

You know Shohei and Clayton and Freddie and Mookie. Teo and Will Smith and Blake Snell and Roki. But do you recall the least heralded Dodger of all? Well, that’s not exactly fair, and I didn’t even name all the famous Dodgers, but here’s the point: I’m writing about a Dodger who isn’t one of the guys who seem to steal every headline.

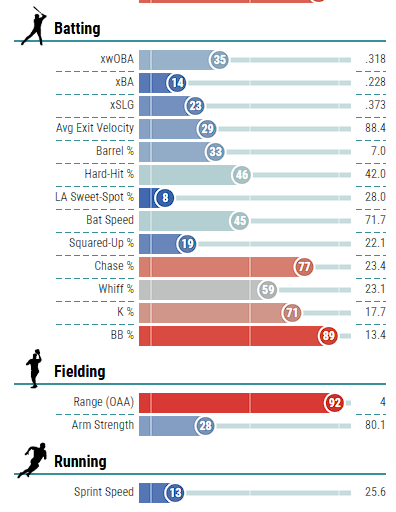

Meet Andy Pages, the Dodgers’ everyday center fielder. A year ago, Pages was just another hopeful, the latest in a line of plus-bat, where-can-he-play-defense-though options cycling through the corners in Chavez Ravine. Pages’ prospect reports paint a clear picture: a swing built for lift, plenty of swing-and-miss, and sneaky athleticism that exploded after Pages returned from shoulder surgery. In 116 games of big league play, he took over center field (mostly out of necessity — he looked stretched there at times) and posted a league average batting line, though without the home run power that evaluators expected from him.

If you could freeze time there and give the Dodgers the option of having exactly that Pages for the next five years, I think they would have begrudgingly accepted it. Teams as full of stars as Los Angeles’ current squad need role players to fill the cracks in the roster, and outfielders who can handle center and hit at least okay are always in high demand. That isn’t to say that there weren’t encouraging signs – Pages’ athleticism was better than advertised and he showed plus bat speed – but a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, and he was already an excellent cog in the machine even without fully unlocking his power.

Flash-forward to this season. Pages started the year playing center and batting ninth. That’s the lineup spot for a complementary piece, a defensive specialist or fourth outfielder. He started slow, with a 70 wRC+ over his first month of play. The Dodgers didn’t have better options defensively, and in fact, Pages looked downright smooth out there, both to my eyes and to defensive model grades. When your team posts a collective 126 wRC+ for the months of March and April (for the months of May and June so far, too — this team is pretty good!), you can live with a below-average hitter playing a tough defensive position, so the Dodgers kept running Pages out there, slow start and all. And that brings us to April 22, when Pages got hot and didn’t stop. Read the rest of this entry »