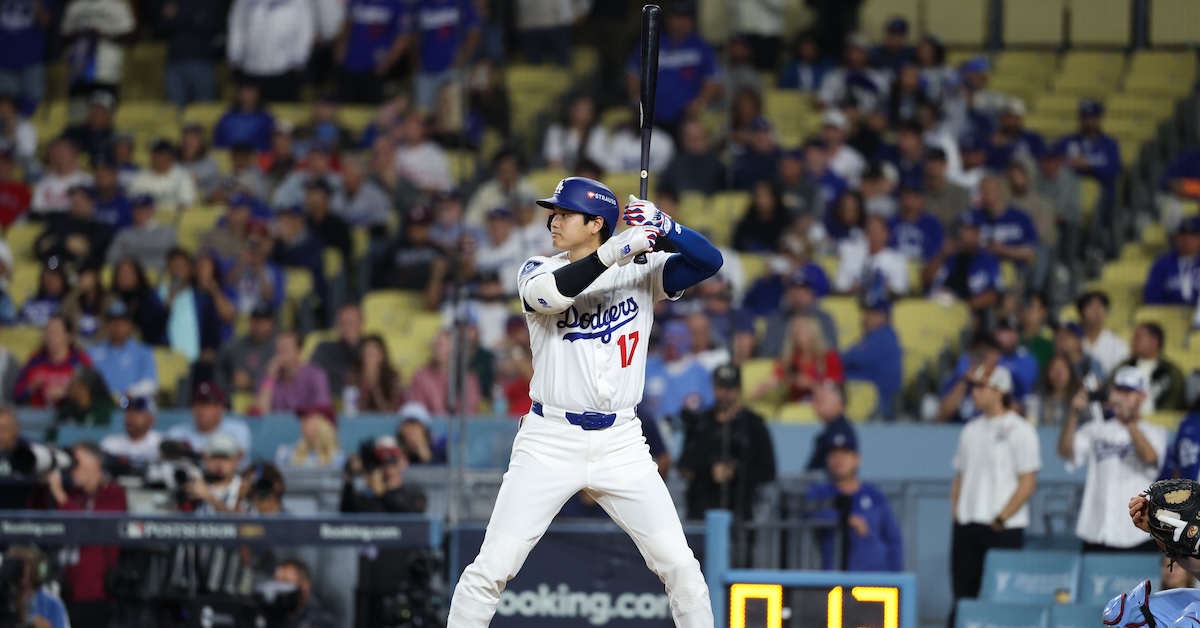

Dodgers Outlast Blue Jays in 18 Innings To Win Epic World Series Game 3

An all-time World Series classic was played on October 27, 1991. That was the Game 7 where Jack Morris and John Smoltz matched zeros until the Minnesota Twins ultimately edged the Atlanta Braves 1-0 in 10 innings. Thirteen years later, on that same date in 2004, the Boston Red Sox won their first World Series championship since 1918. In both cases, baseball history was made in memorable fashion.

What took place on October 27, 2025 at Dodger Stadium ranks right up there with the best World Series games ever played. In an affair that lasted deep into the night and featured heroics from multiple players, it was Freddie Freeman who finally ended it. Leading off the bottom of the 18th inning, the Dodgers first baseman launched a home run to straightaway center field to walk off the Blue Jays, 6-5, in Game 3 and give Los Angeles a two-games-to-one lead in the World Series.

The game started uneventfully, with Dodgers starter Tyler Glasnow retiring the side in order in the first. But from that point forward the word “uneventful” was nowhere to be found — not for the remainder of a Monday night that turned into the wee hours of Tuesday for most of Canada and the continental United States, for all but the time zone in which Game 3 was played. Read the rest of this entry »