Kyle Hendricks Takes a Hometown Discount

The outbreak of extension fever might now be classified as a pandemic. Tuesday brought news not only of Jacob deGrom’s four-year, $120.5 million deal for 2020-23 (bringing his total take over the next five seasons to $137.5 million) but also of that of Kyle Hendricks. The 29-year-old righty has agreed to a four-year, $55.5 million extension with the Cubs for that same four-year period, buying out his final year of arbitration eligibility and what would have been his first three years of free agency at a rather club-friendly price.

Hendricks has been a reliable mid-rotation presence since joining the Cubs in July 2014; the former eighth-round pick out of Dartmouth had been acquired from the Rangers at the July 31 deadline just two years earlier in exchange for Ryan Dempster. He provided his share of magic in Chicago’s epic 2016 season, leading the NL in ERA (2.13), ranking fourth in FIP (3.20), and seventh in WAR (4.1), then placing third in the NL Cy Young voting behind Max Scherzer and teammate Jon Lester. That October, Hendricks posted a 1.42 ERA in five postseason starts, though only twice was he allowed to go even five full innings; his best outing was a 7.1-inning shutout of the Dodgers in the NLCS clincher. In 2018 he threw a career-high 199 innings and delivered a 3.44 ERA, 3.78 FIP, and 3.5 WAR, numbers that respectively ranked 13th, 12th, and 11th in the league. For the 2015-18 period, his 3.14 ERA ranked 14th in the majors, his 13.3 WAR 19th, his 3.54 FIP 28th.

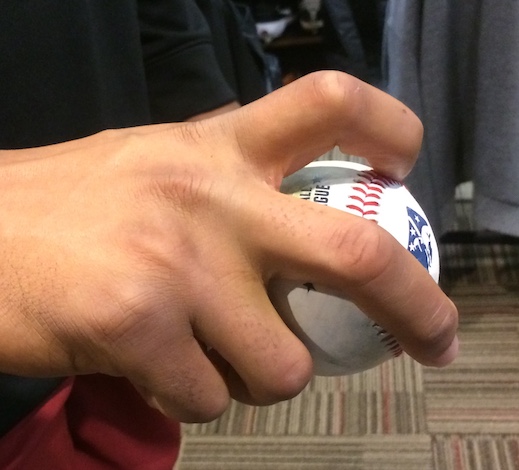

Hendricks has done this not by overpowering hitters but by limiting hard contact, generating a steady stream of groundballs, and rarely walking hitters. Via Pitch Info, his average fastball velocity — whether we’re talking about his four-seamer, which in 2018 averaged 87.7 mph and was thrown 17.5% of the time, or his sinker, which averaged 87.1 mph and was thrown 44.3% of the time — was the majors’ lowest among qualified starters, about two clicks slower than runner-up Mike Leake for either offering. He accompanies those pitches with an excellent changeup, which in 2018 generated a 19.8% swinging strike rate and just a 36 wRC+ (.180/.201/.288) on plate appearances ending with the pitch. According to Statcast, the 85.2 mph average exit velocity he yielded ranked in the 92nd percentile, and his hard hit rate of 30.6% in the 83rd percentile.

Hendricks is already signed for 2019 at a salary of $7.405 million. Under the terms of the new deal, he’s guaranteed $12 million in 2020, and then $14 million annually from 2021-23. If he finishes second or third in the Cy Young balloting, his base salaries for each season thereafter increase by $1 million; if he wins the award, they increase by $2 million. He has a $16 million vesting option for 2024 based upon a top-three finish in the Cy Young voting in 2020 and being deemed healthy for the 2021 season; if it doesn’t vest, it becomes a club option. Per the Athletic’s Ken Rosenthal, the deal can max out at $78.9 million.

(I’m not quite sure how he arrived at that figure, both with respect to the decimal and the slim possibility of multiple Cy Young results that as I understand it, would push his value even higher. Imagine him winning the 2020 Cy Young award — go on, I’ll wait — thereby making each of the next three years worth $16 million and vesting the $16 million option for 2024; that’s $12 million plus four times $16 million, or $76 million all told. If he wins again in 2021, he’s banked $28 million, and then his salary should escalate again, to $18 million for at least the next two seasons, which pushes his total to $80 million even if the vesting option remains unchanged.)

Escalators aside, Hendricks’ four-year, $55.5 million guarantee looks rather light when compared to the four-year, $68 million free agent deal that Nathan Eovaldi, who’s also 29, inked with the Red Sox in December and the four-year, $68 million extension Miles Mikolas, who’s 30, signed earlier this month; the latter covers 2020-23 as well and buys out just one year of free agency. Mikolas was the most valuable of the three in 2018, producing 4.3 WAR in 200.2 innings, but in 91.1 previous major league innings before going to Japan, he was below replacement level (-0.2 WAR). Eovaldi produced 2.2 WAR in 111 innings last year for the Rays and Red Sox, but over the 2015-18 period produced just 6.1 WAR because he missed all of 2017 and time on either side of that due to his second Tommy John surgery. Expand the window back to 2014, when Eovaldi set a career high with 3.3 WAR and Hendricks had 1.6 in a 13-start rookie showing, and the gap closes, but it still favors Hendricks, 15.0 to 9.4.

What’s done is done; the question is what the three players will do going forward. Towards that end, Dan Szymborski provided ZiPS projections for the trio:

| Year | Hendricks | Mikolas | Eovaldi |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 1.9 |

| 2020 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 1.8 |

| 2021 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 1.7 |

| 2022 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| 2023 | 2.4 | 2.1 | |

| 4-year totals | 11.2 | 10.0 | 7.0 |

Even while excluding the upcoming seasons of Hendricks and Mikolas, which project to be the most valuable, to focus on the four-year deals, both project better than Eovaldi due in part to the latter’s injury history; ZiPS projects him for a maximum of 110.2 innings (2019) and a four-year total of 411, compared to 602.2 for Hendricks and 587 for Mikolas. Hendricks projects as the most valuable over the four covered years, yet he’s being paid the least, and the one year of arbitration eligibility doesn’t explain the difference , particularly given that Mikolas’ deal covers three years of arb-eligibility.

(As multiple readers have reminded me, Mikolas’ initial contract included language that made him a free agent following the 2019 season, not subject to the arbitration system.)

Even if I place all three on an equal footing by prorating their projections to a flat 180 innings per year — a level Hendriks has reached three times in the majors, Eovaldi and Mikolas just once (twice if you count his 2017 season in Japan) — the Cubs’ righty gets the performance edge, which only underscores the discrepancy in pay:

| Year | Hendricks | Mikolas | Eovaldi |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.1 |

| 2020 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.1 |

| 2021 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| 2022 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 3.1 |

| 2023 | 3.2 | 2.8 | |

| 4-year totals | 13.4 | 12.2 | 12.3 |

Even tossing that optimistic scenario aside, reminding ourselves again about Hendricks’ arb-eligible year, and foregoing any assumptions about inflation, we can understand that his contract comes out to about $5 million per win, at a time when we’re debating whether $8 million or $9 million per win is the right assumption. That’s a very club-friendly deal, to say the least.

Hendricks’ deal guarantees that at least one member of this year’s Cubs rotation (which ranks 10th in our depth charts) will be around in 2021, barring a trade. Cole Hamels will be a free agent after this season, and Yu Darvish, whose first year of a six-year, $126-million deal was an injury-shortened mess, can be if he chooses to opt out after the season, which seems like a long shot. Jose Quintana has a very affordable $10.5 million option for 2020, while Lester is signed through 2020 with a $25 million mutual option that can vest if he throws 200 innings in 2020 or 400 innings in 2019-20. Tyler Chatwood is signed through 2020 as well, but he was so bad last year that he doesn’t even project to be part of this year’s starting five, so who knows what happens down the road.

It’s not hard to understand why the Cubs want to keep Hendricks around, particularly given the glowing words team president Theo Epstein used in discussing the extension (“a wonderful representative of the whole Cubs organization… someone who is incredibly dependable, trustworthy, hardworking, thoughtful”). And it’s not hard to understand why Hendricks wants to stick around, given how strong the team has been during his tenure. Still, in light of the prices being paid elsewhere for players foregoing free agency, it’s not hard to think he could have done better, either.