The Dodgers Get Shifty

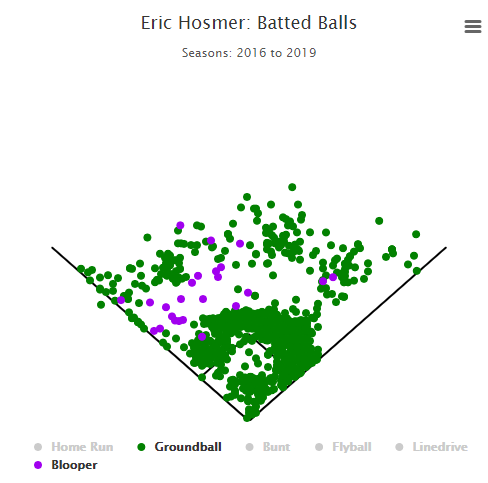

Eric Hosmer is a hard man to shift against. Though he fits the two main criteria for an overshift (namely: he’s left-handed and plays baseball), that’s where his list as an ideal candidate ends. If ever anyone was going to poke a groundball the opposite way, it would be Hosmer — his groundball rate is perennially among the league’s highest, and he hits a fair number of them to the opposite field. Teams generally agree — he’s faced a shift in fewer than half of his bases-empty plate appearances this year, and only 40.7% overall. Both place him in the bottom third of left-handed batters when it comes to the defensive alignment.

You don’t have to dig into his groundball numbers for long to work out why. The reasoning behind a shift is simple; hitters pull groundballs. League-wide, a whopping 55.5% of groundballs have been pulled, against only 12.1% hit the opposite way. The split is the same regardless of handedness, but first base is conveniently located on the lefty pull side of the field, which makes shifting a left-handed batter a high-percentage move.

For some reason, though, Hosmer doesn’t fit that mold. In 2019, he’s pulled only 46.4% of his groundballs, almost exactly equivalent to his career average of 46.3%. He’s at 16.3% opposite-field groundballs for his career over a whopping 2,263 grounders. His pull rate is in the bottom 20% of batters this year, and was in the bottom 3% last year, the bottom 10% two years ago, the bottom 15% for his career — you get the idea.

This isn’t to say there’s no merit to shifting against Hosmer — you’d need a more detailed mapping of infielder speeds and groundball exit velocity to work the math out perfectly. But look at his groundball (and blooper) distribution from 2016 to 2019 and tell me you want to shift against this: