Expected Home Run Rate, 2020 Edition

Last year, I came up with a simple idea: estimate home runs based on exit velocity. That sounds pretty straightforward, and it mostly is. For example, here are your odds of hitting a home run at various exit velocities when you put the ball in the air in 2020:

Of course, some caveats apply. I’m only looking at batted balls between 15 and 45 degrees, and the sample size is still small. But for the most part, and excluding the vagaries of that small sample, the conclusion makes sense. Hit the ball harder, and you’ll find more home runs.

Of course, real life is notoriously fickle. Sometimes you mash the ball and it’s a degree too low, or you hit it to the wrong part of the ballpark, or a gust of wind takes it. Sometimes you play in Yankee Stadium and get a cheapie, or smoke a line drive that leaves a dent in the Green Monster. Sometimes you make perfect contact, and it’s at 15 degrees instead of 25 so it’s a smashed single to right instead of a bat flip highlight.

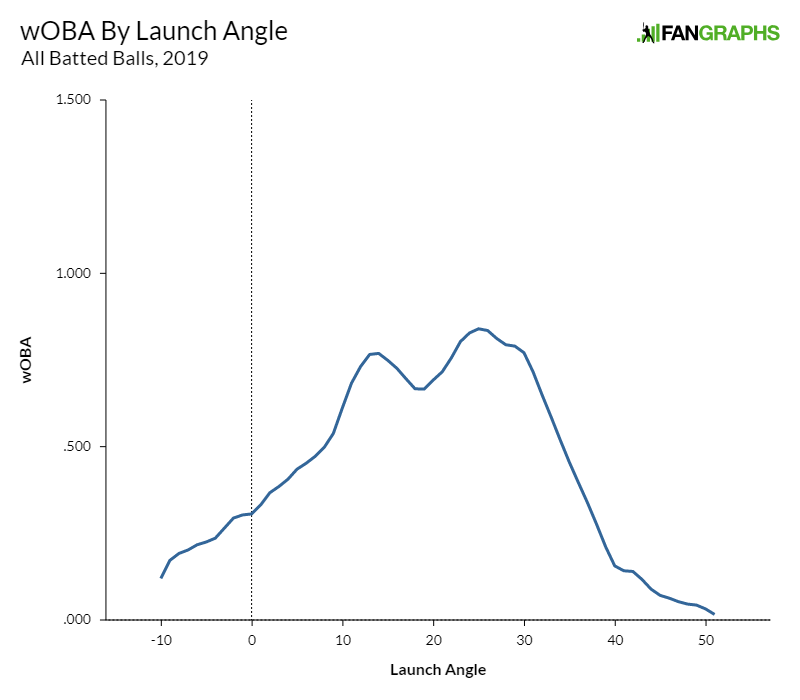

Wait — hit it at the wrong angle? That seems like something in a batter’s control. It partially is, but I’ve chosen to exclude it for two reasons. First, I’ll point again to this excellent Alex Chamberlain article. You should really read it, but the conclusion is basically this: batters control exit velocity and pitchers control launch angle. That’s not exclusively true, and there are obviously fly ball and groundball hitters, but if you start giving batters credit for the exact angle of their batted balls instead of just generally saying “in the air” or “not,” you might be going too far.

Second, this way is simpler! Simplicity has value. Overspecify a model, and you can get very precise results that are also hard to interpret, or that depend heavily on small fluctuations in initial conditions. That’s not to say that such a model is a bad idea — merely that it’s not strictly upside to add more and more gadgets and whizbangs to it. You also risk losing the signal you’re looking for, which in this case is the ability to absolutely hit the snot out of the ball, sending it skyward at stupid speeds. Read the rest of this entry »