For the 22nd consecutive season, the ZiPS projection system is unleashing a full set of prognostications. For more information on the ZiPS projections, please consult this year’s introduction, as well as MLB’s glossary entry. The team order is selected by lot, and the next team up is the Toronto Blue Jays.

Batters

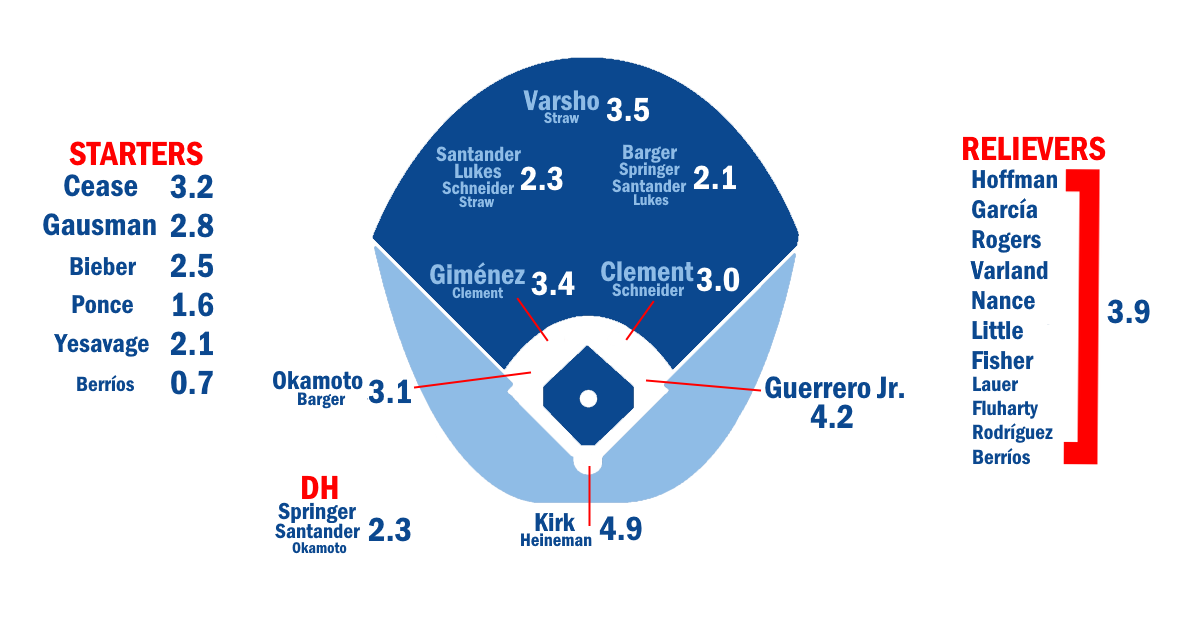

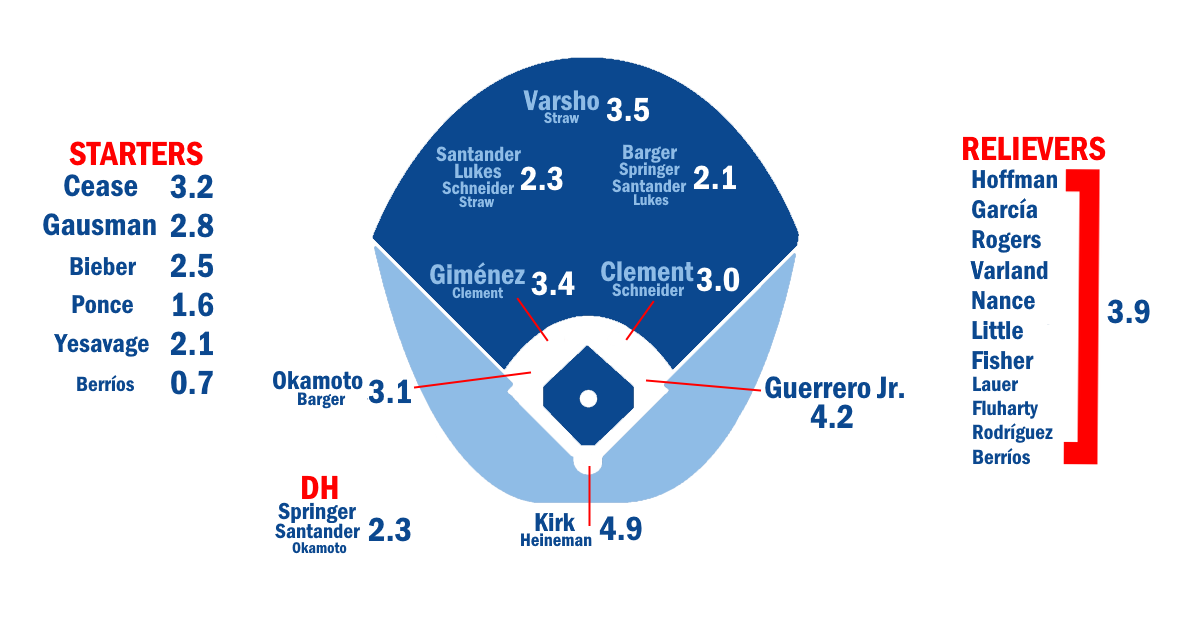

The Toronto Blue Jays were just two runs away from winning the World Series, so suffice it to say, 2025 was a pretty successful season. Even with a disappointing first year from Anthony Santander, the Jays were second in the American League in runs scored. The lineup wasn’t just potent at the plate, either, with the team’s position players leading baseball at 44 runs above average in FRV. The pitching, both the rotation and the bullpen, was fairly middling, but given what Toronto got out of its bats, the arms didn’t need to do that much to propel the team deep into the playoffs. Now the Jays seek to finish 2025’s job in a division that won’t make it an easy task. Not that they’re sitting around and waiting; less than a year after extending Vladito for a half billion dollars, they’ve shelled out another $336 million in guaranteed money this winter. Just for context, that’s nearly $100 million more than the rest of the AL East has spent in free agency combined ($249.6 million). Crashing past the final luxury tax threshold certainly fulfills any reasonable definition of going “all in” on winning.

Neither Andrés Giménez nor Ernie Clement has the offensive upside that the recently departed Bo Bichette does, but both are fine defensive players. ZiPS isn’t banking on Kazuma Okamoto being a star or anything, but he should hit for power and be a plus at third if his defense holds up. Completing the infield is Vladimir Guerrero Jr., and while his offensive output was well below his 2024 level, he was still a star-level first baseman last year. With both Davis Schneider and Addison Barger projected as basically league average starters at second and third respectively, there’s impressive infield depth here as well.

Even though he missed half the season, first recovering from offseason shoulder surgery and then a hamstring malady, Daulton Varsho still managed 2.2 WAR in 2025. Varsho is never going to put up impressive batting averages, but he has very good power for the position and plays good defense, and I think most of the remaining locals who were upset that he’s on the roster instead of Gabriel Moreno have quieted down by this point. The corner outfield positions are both in flux, with the exact mix of Santander and George Springer at DH undetermined, but between those two, Schneider, Barger, and Nathan Lukes, who is more than capable of taking the larger piece of a platoon, they ought to get at least average production in the corners and at DH. The Jays have been endlessly linked to Kyle Tucker, and he’d undoubtedly improve the team, but I’m not sure that they wouldn’t get a lot more bang for the buck by signing one of the top pitchers remaining.

Pitchers

Dylan Cease was a solid addition, and forms a quality 1-2 punch with Kevin Gausman. There’s also a lot of upside in Trey Yesavage — you saw how he pitched in the postseason — and a healthy Shane Bieber could be a big plus. But a pitcher with just a single year of professional experience, or one who comes with Bieber’s injury history, carries real risks as well. Cody Ponce is interesting, and a good risk given the upside, but you can’t completely ignore that before his huge season in the KBO, he really wasn’t very good at all in Japan. If José Berríos gets back on track, well, having too much pitching has never actually been a real problem; the Dodgers over the last five years could tell you about that. I can’t help but think that for as good as the Cease signing was, adding Framber Valdez or Ranger Suárez is still a good idea, as it would lower the rotation’s downside considerably and make the Jays the AL East favorite by a win or two.

Despite the middle-of-the-pack results last year, ZiPS is actually rather enamored with Toronto’s relief corps. While it doesn’t see the team as having a Jhoan Duran or Mason Miller at the top of the ‘pen, with the exception of Yimi García, the computer projects every pitcher with 30 relief innings on our depth chart to have an ERA under 4.00 as a reliever. That even holds true if you stretch things out further, to Chase Lee and Lazaro Estrada. The soft-tossing Tyler Rogers was the big bullpen addition, practically a unicorn in that he’s an exceedingly unusual submariner who doesn’t have significant platoon splits. I don’t think the Jays really need to do much else here, and their deep store of talent might even justify them trading a reliever or two if one of the contenders with bullpen issues fails to shore things up over the next two months.

All told, the Blue Jays look to be neck-and-neck with the Red Sox, and slightly better than the Yankees, in the AL East. As for the Orioles, you’ll have to wait for that ZiPS post later this week.

Ballpark graphic courtesy Eephus League. Depth charts constructed by way of those listed here. Size of player names is very roughly proportional to Depth Chart playing time. The final team projections may differ considerably from our Depth Chart playing time.

Batters – Standard

| Player |

B |

Age |

PO |

PA |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

BB |

SO |

SB |

CS |

| Vladimir Guerrero Jr. |

R |

27 |

1B |

663 |

578 |

93 |

168 |

32 |

0 |

32 |

102 |

75 |

89 |

5 |

2 |

| Alejandro Kirk |

R |

27 |

C |

476 |

418 |

43 |

113 |

17 |

0 |

14 |

62 |

48 |

56 |

1 |

0 |

| Bo Bichette |

R |

28 |

SS |

598 |

554 |

73 |

162 |

33 |

1 |

19 |

85 |

38 |

97 |

5 |

4 |

| Andrés Giménez |

L |

27 |

SS |

520 |

466 |

60 |

116 |

19 |

2 |

12 |

60 |

30 |

90 |

19 |

3 |

| Kazuma Okamoto |

R |

30 |

3B |

495 |

434 |

58 |

109 |

23 |

0 |

23 |

82 |

50 |

93 |

1 |

1 |

| Daulton Varsho |

L |

29 |

CF |

453 |

410 |

64 |

93 |

17 |

3 |

24 |

71 |

34 |

115 |

7 |

3 |

| Ernie Clement |

R |

30 |

2B |

502 |

469 |

64 |

126 |

24 |

2 |

10 |

56 |

21 |

49 |

6 |

3 |

| George Springer |

R |

36 |

DH |

548 |

480 |

80 |

123 |

20 |

2 |

22 |

73 |

58 |

107 |

13 |

2 |

| Davis Schneider |

R |

27 |

LF |

444 |

378 |

56 |

84 |

17 |

2 |

18 |

58 |

58 |

126 |

6 |

1 |

| Addison Barger |

L |

26 |

3B |

517 |

467 |

65 |

114 |

27 |

1 |

21 |

75 |

44 |

120 |

4 |

2 |

| Nathan Lukes |

L |

31 |

RF |

392 |

351 |

48 |

94 |

17 |

2 |

9 |

49 |

32 |

61 |

3 |

2 |

| Joey Loperfido |

L |

27 |

CF |

483 |

436 |

60 |

107 |

22 |

2 |

15 |

65 |

32 |

131 |

10 |

4 |

| RJ Schreck |

L |

25 |

RF |

422 |

360 |

54 |

78 |

13 |

2 |

17 |

61 |

48 |

100 |

4 |

1 |

| Anthony Santander |

B |

31 |

DH |

508 |

451 |

59 |

103 |

21 |

0 |

27 |

78 |

48 |

114 |

1 |

0 |

| Jonatan Clase |

B |

24 |

CF |

514 |

461 |

64 |

103 |

22 |

4 |

12 |

58 |

43 |

148 |

28 |

7 |

| Leo Jiménez |

R |

25 |

SS |

352 |

304 |

45 |

68 |

14 |

1 |

7 |

41 |

28 |

75 |

2 |

2 |

| Myles Straw |

R |

31 |

CF |

410 |

368 |

53 |

87 |

15 |

3 |

4 |

32 |

31 |

74 |

15 |

2 |

| Charles McAdoo |

R |

24 |

3B |

497 |

454 |

56 |

103 |

20 |

2 |

15 |

63 |

36 |

153 |

16 |

4 |

| Tyler Heineman |

B |

35 |

C |

184 |

157 |

21 |

35 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

18 |

16 |

34 |

3 |

1 |

| Carlos Mendoza |

L |

26 |

3B |

438 |

375 |

58 |

89 |

13 |

2 |

5 |

47 |

44 |

71 |

9 |

5 |

| Brandon Valenzuela |

B |

25 |

C |

437 |

396 |

41 |

81 |

16 |

1 |

12 |

50 |

36 |

119 |

2 |

1 |

| Ty France |

R |

31 |

1B |

509 |

457 |

53 |

113 |

23 |

0 |

12 |

59 |

30 |

91 |

1 |

0 |

| Rodolfo Castro |

B |

27 |

SS |

475 |

427 |

52 |

92 |

17 |

2 |

15 |

62 |

37 |

125 |

8 |

5 |

| Nick Goodwin |

R |

24 |

2B |

370 |

327 |

45 |

67 |

8 |

2 |

9 |

42 |

29 |

87 |

5 |

2 |

| Adrian Pinto |

R |

23 |

2B |

116 |

104 |

18 |

22 |

3 |

0 |

4 |

16 |

8 |

24 |

3 |

1 |

| Riley Tirotta |

R |

27 |

3B |

439 |

391 |

48 |

86 |

16 |

2 |

12 |

51 |

41 |

145 |

7 |

3 |

| Isiah Kiner-Falefa |

R |

31 |

SS |

435 |

403 |

44 |

99 |

15 |

2 |

4 |

41 |

21 |

72 |

13 |

3 |

| Ismael Munguia |

L |

27 |

CF |

359 |

322 |

47 |

78 |

13 |

1 |

5 |

40 |

21 |

37 |

15 |

6 |

| Arjun Nimmala |

R |

20 |

SS |

535 |

488 |

65 |

96 |

20 |

4 |

13 |

65 |

35 |

154 |

8 |

2 |

| Victor Arias |

L |

22 |

CF |

468 |

426 |

60 |

98 |

16 |

5 |

8 |

50 |

34 |

122 |

10 |

5 |

| Cutter Coffey |

R |

22 |

3B |

443 |

404 |

56 |

83 |

18 |

0 |

11 |

50 |

32 |

126 |

6 |

2 |

| Devonte Brown |

R |

26 |

CF |

356 |

313 |

38 |

62 |

11 |

1 |

9 |

40 |

36 |

131 |

8 |

0 |

| Sean Keys |

L |

23 |

3B |

518 |

452 |

51 |

84 |

18 |

2 |

15 |

61 |

52 |

144 |

4 |

1 |

| Aaron Parker |

R |

23 |

C |

267 |

248 |

26 |

50 |

12 |

1 |

7 |

32 |

15 |

69 |

2 |

0 |

| Eloy Jiménez |

R |

29 |

RF |

356 |

327 |

30 |

79 |

13 |

0 |

10 |

43 |

25 |

71 |

1 |

0 |

| Josh Kasevich |

R |

25 |

SS |

406 |

372 |

39 |

88 |

13 |

0 |

2 |

34 |

28 |

57 |

4 |

3 |

| Joshua Rivera |

R |

25 |

SS |

413 |

372 |

39 |

72 |

12 |

1 |

6 |

34 |

36 |

151 |

2 |

1 |

| Geovanny Planchart |

R |

24 |

C |

235 |

209 |

20 |

38 |

7 |

1 |

2 |

19 |

22 |

60 |

0 |

0 |

| Eddie Micheletti Jr. |

L |

24 |

RF |

457 |

395 |

40 |

76 |

20 |

2 |

11 |

53 |

48 |

89 |

2 |

0 |

| Phil Clarke |

L |

28 |

C |

264 |

231 |

27 |

53 |

8 |

0 |

3 |

25 |

26 |

37 |

2 |

0 |

| Edward Duran |

R |

22 |

C |

422 |

384 |

41 |

81 |

14 |

3 |

5 |

41 |

27 |

101 |

5 |

3 |

| Jorge Burgos |

L |

23 |

1B |

410 |

374 |

41 |

75 |

15 |

2 |

15 |

57 |

29 |

119 |

1 |

1 |

| Jace Bohrofen |

L |

24 |

LF |

395 |

353 |

41 |

67 |

15 |

2 |

12 |

48 |

36 |

143 |

6 |

1 |

| Rainer Nunez |

R |

25 |

1B |

411 |

382 |

39 |

91 |

13 |

1 |

10 |

47 |

24 |

107 |

1 |

0 |

| Alexis Hernandez |

R |

23 |

RF |

296 |

268 |

32 |

57 |

10 |

1 |

6 |

31 |

21 |

79 |

9 |

2 |

| Brennan Orf |

L |

24 |

1B |

174 |

150 |

19 |

27 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

16 |

21 |

54 |

1 |

0 |

| Cade Doughty |

R |

25 |

SS |

397 |

366 |

36 |

80 |

14 |

1 |

7 |

39 |

20 |

112 |

3 |

2 |

| Damiano Palmegiani |

R |

26 |

1B |

436 |

386 |

43 |

74 |

17 |

1 |

13 |

58 |

35 |

135 |

1 |

1 |

| Robert Brooks |

R |

27 |

C |

151 |

137 |

8 |

23 |

4 |

0 |

3 |

15 |

11 |

60 |

0 |

1 |

| Bryce Arnold |

R |

24 |

LF |

322 |

286 |

38 |

53 |

11 |

1 |

8 |

38 |

25 |

102 |

4 |

0 |

| Ryan McCarty |

R |

27 |

2B |

419 |

378 |

40 |

77 |

16 |

2 |

7 |

43 |

30 |

123 |

5 |

4 |

| Yohendrick Pinango |

L |

24 |

LF |

514 |

467 |

49 |

104 |

21 |

2 |

12 |

57 |

42 |

116 |

5 |

2 |

| Tucker Toman |

B |

22 |

3B |

445 |

407 |

47 |

82 |

17 |

1 |

5 |

42 |

27 |

137 |

2 |

0 |

| Eddinson Paulino |

L |

23 |

2B |

407 |

376 |

39 |

74 |

14 |

2 |

10 |

44 |

25 |

117 |

6 |

4 |

| Alex De Jesus |

R |

24 |

3B |

364 |

331 |

35 |

66 |

13 |

2 |

5 |

33 |

28 |

125 |

3 |

2 |

| Jacob Sharp |

R |

24 |

C |

242 |

217 |

20 |

39 |

7 |

0 |

3 |

24 |

14 |

63 |

1 |

1 |

| Jay Harry |

L |

23 |

SS |

391 |

358 |

37 |

69 |

13 |

1 |

7 |

39 |

25 |

97 |

5 |

3 |

| Je’Von Ward |

L |

26 |

RF |

391 |

342 |

50 |

67 |

14 |

2 |

8 |

38 |

45 |

126 |

4 |

2 |

| Nicolas Deschamps |

L |

23 |

C |

164 |

143 |

14 |

22 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

15 |

13 |

71 |

0 |

1 |

| J.R. Freethy |

B |

23 |

2B |

361 |

313 |

44 |

61 |

10 |

2 |

5 |

34 |

38 |

100 |

4 |

2 |

| Jacob Wetzel |

L |

26 |

RF |

314 |

280 |

34 |

52 |

11 |

3 |

6 |

30 |

29 |

91 |

5 |

2 |

| Peyton Williams |

L |

25 |

1B |

352 |

323 |

32 |

64 |

12 |

1 |

9 |

38 |

24 |

118 |

0 |

0 |

| Gabriel Martinez |

R |

23 |

RF |

386 |

359 |

32 |

75 |

14 |

1 |

5 |

34 |

21 |

84 |

2 |

1 |

| Hedbert Perez |

L |

23 |

DH |

338 |

308 |

28 |

54 |

9 |

2 |

10 |

35 |

28 |

122 |

4 |

2 |

| Jackson Hornung |

R |

25 |

1B |

423 |

387 |

45 |

83 |

16 |

3 |

7 |

44 |

29 |

151 |

3 |

0 |

| Carter Cunningham |

L |

25 |

1B |

405 |

355 |

50 |

63 |

10 |

2 |

12 |

43 |

42 |

162 |

6 |

3 |

| Sam Shaw |

L |

21 |

2B |

317 |

284 |

35 |

52 |

10 |

2 |

6 |

30 |

30 |

83 |

4 |

0 |

| Peyton Powell |

L |

25 |

1B |

302 |

269 |

27 |

51 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

19 |

29 |

101 |

0 |

3 |

Batters – Advanced

| Player |

PA |

BA |

OBP |

SLG |

OPS+ |

ISO |

BABIP |

Def |

WAR |

wOBA |

3YOPS+ |

RC |

| Vladimir Guerrero Jr. |

663 |

.291 |

.376 |

.512 |

142 |

.221 |

.298 |

-1 |

4.2 |

.378 |

138 |

113 |

| Alejandro Kirk |

476 |

.270 |

.347 |

.411 |

109 |

.141 |

.284 |

14 |

4.1 |

.331 |

107 |

60 |

| Bo Bichette |

598 |

.292 |

.339 |

.458 |

118 |

.166 |

.326 |

-5 |

3.4 |

.344 |

113 |

89 |

| Andrés Giménez |

520 |

.249 |

.315 |

.376 |

90 |

.127 |

.286 |

7 |

2.7 |

.303 |

90 |

60 |

| Kazuma Okamoto |

495 |

.251 |

.337 |

.463 |

118 |

.212 |

.270 |

-2 |

2.6 |

.342 |

114 |

68 |

| Daulton Varsho |

453 |

.227 |

.290 |

.459 |

102 |

.232 |

.255 |

7 |

2.5 |

.319 |

98 |

57 |

| Ernie Clement |

502 |

.269 |

.302 |

.392 |

90 |

.124 |

.283 |

11 |

2.2 |

.300 |

88 |

58 |

| George Springer |

548 |

.256 |

.343 |

.444 |

115 |

.188 |

.288 |

0 |

2.2 |

.342 |

107 |

77 |

| Davis Schneider |

444 |

.222 |

.331 |

.421 |

106 |

.199 |

.282 |

6 |

2.0 |

.329 |

105 |

54 |

| Addison Barger |

517 |

.244 |

.313 |

.441 |

105 |

.197 |

.285 |

-3 |

1.9 |

.325 |

107 |

66 |

| Nathan Lukes |

392 |

.268 |

.332 |

.405 |

103 |

.137 |

.302 |

9 |

1.8 |

.322 |

97 |

49 |

| Joey Loperfido |

483 |

.245 |

.309 |

.408 |

96 |

.163 |

.317 |

-2 |

1.4 |

.312 |

96 |

59 |

| RJ Schreck |

422 |

.217 |

.327 |

.406 |

101 |

.189 |

.251 |

3 |

1.4 |

.323 |

104 |

49 |

| Anthony Santander |

508 |

.228 |

.309 |

.455 |

107 |

.227 |

.245 |

0 |

1.3 |

.328 |

102 |

64 |

| Jonatan Clase |

514 |

.223 |

.294 |

.367 |

81 |

.144 |

.302 |

2 |

1.2 |

.290 |

86 |

58 |

| Leo Jiménez |

352 |

.224 |

.319 |

.345 |

84 |

.121 |

.275 |

0 |

1.0 |

.299 |

88 |

35 |

| Myles Straw |

410 |

.236 |

.295 |

.326 |

72 |

.090 |

.286 |

7 |

1.0 |

.276 |

69 |

39 |

| Charles McAdoo |

497 |

.227 |

.288 |

.379 |

82 |

.152 |

.308 |

0 |

0.9 |

.292 |

87 |

54 |

| Tyler Heineman |

184 |

.223 |

.313 |

.325 |

77 |

.102 |

.267 |

5 |

0.9 |

.288 |

71 |

17 |

| Carlos Mendoza |

438 |

.237 |

.331 |

.323 |

82 |

.085 |

.281 |

1 |

0.9 |

.297 |

82 |

44 |

| Brandon Valenzuela |

437 |

.205 |

.272 |

.341 |

68 |

.136 |

.260 |

4 |

0.7 |

.270 |

72 |

38 |

| Ty France |

509 |

.247 |

.318 |

.376 |

91 |

.129 |

.285 |

2 |

0.6 |

.307 |

89 |

55 |

| Rodolfo Castro |

475 |

.215 |

.286 |

.370 |

80 |

.155 |

.268 |

-6 |

0.3 |

.288 |

80 |

49 |

| Nick Goodwin |

370 |

.205 |

.289 |

.324 |

69 |

.119 |

.251 |

2 |

0.3 |

.274 |

74 |

32 |

| Adrian Pinto |

116 |

.212 |

.281 |

.356 |

74 |

.144 |

.237 |

1 |

0.2 |

.282 |

78 |

11 |

| Riley Tirotta |

439 |

.220 |

.301 |

.363 |

82 |

.143 |

.316 |

-5 |

0.2 |

.293 |

84 |

45 |

| Isiah Kiner-Falefa |

435 |

.246 |

.290 |

.323 |

69 |

.077 |

.291 |

-3 |

0.1 |

.271 |

66 |

42 |

| Ismael Munguia |

359 |

.242 |

.307 |

.335 |

78 |

.093 |

.261 |

-4 |

0.1 |

.287 |

78 |

39 |

| Arjun Nimmala |

535 |

.197 |

.260 |

.334 |

63 |

.137 |

.259 |

1 |

0.0 |

.261 |

71 |

45 |

| Victor Arias |

468 |

.230 |

.295 |

.347 |

77 |

.117 |

.304 |

-4 |

0.0 |

.283 |

81 |

48 |

| Cutter Coffey |

443 |

.205 |

.271 |

.332 |

65 |

.127 |

.270 |

2 |

-0.1 |

.266 |

73 |

38 |

| Devonte Brown |

356 |

.198 |

.289 |

.326 |

70 |

.128 |

.306 |

-4 |

-0.1 |

.276 |

74 |

31 |

| Sean Keys |

518 |

.186 |

.282 |

.334 |

70 |

.148 |

.235 |

-2 |

-0.1 |

.275 |

76 |

44 |

| Aaron Parker |

267 |

.202 |

.255 |

.343 |

63 |

.141 |

.250 |

-3 |

-0.2 |

.262 |

71 |

22 |

| Eloy Jiménez |

356 |

.242 |

.298 |

.373 |

84 |

.131 |

.280 |

-3 |

-0.2 |

.293 |

83 |

37 |

| Josh Kasevich |

406 |

.237 |

.293 |

.288 |

62 |

.051 |

.275 |

-1 |

-0.2 |

.262 |

65 |

33 |

| Joshua Rivera |

413 |

.194 |

.265 |

.280 |

51 |

.086 |

.307 |

4 |

-0.2 |

.246 |

54 |

28 |

| Geovanny Planchart |

235 |

.182 |

.264 |

.254 |

44 |

.072 |

.245 |

1 |

-0.3 |

.237 |

46 |

14 |

| Eddie Micheletti Jr. |

457 |

.192 |

.293 |

.337 |

74 |

.145 |

.220 |

1 |

-0.3 |

.282 |

76 |

39 |

| Phil Clarke |

264 |

.229 |

.318 |

.303 |

73 |

.074 |

.262 |

-8 |

-0.3 |

.282 |

71 |

23 |

| Edward Duran |

422 |

.211 |

.275 |

.302 |

60 |

.091 |

.273 |

-2 |

-0.3 |

.258 |

60 |

34 |

| Jorge Burgos |

410 |

.201 |

.263 |

.372 |

73 |

.171 |

.250 |

4 |

-0.3 |

.276 |

79 |

37 |

| Jace Bohrofen |

395 |

.190 |

.273 |

.346 |

70 |

.156 |

.278 |

2 |

-0.4 |

.273 |

76 |

35 |

| Rainer Nunez |

411 |

.238 |

.287 |

.356 |

76 |

.118 |

.306 |

1 |

-0.4 |

.282 |

80 |

39 |

| Alexis Hernandez |

296 |

.213 |

.281 |

.325 |

67 |

.112 |

.279 |

-1 |

-0.5 |

.270 |

70 |

27 |

| Brennan Orf |

174 |

.180 |

.293 |

.287 |

62 |

.107 |

.266 |

-1 |

-0.5 |

.267 |

63 |

13 |

| Cade Doughty |

397 |

.219 |

.266 |

.320 |

61 |

.101 |

.296 |

-3 |

-0.5 |

.259 |

62 |

33 |

| Damiano Palmegiani |

436 |

.192 |

.278 |

.342 |

70 |

.150 |

.256 |

4 |

-0.5 |

.275 |

72 |

37 |

| Robert Brooks |

151 |

.168 |

.238 |

.263 |

39 |

.095 |

.270 |

-1 |

-0.5 |

.227 |

44 |

9 |

| Bryce Arnold |

322 |

.185 |

.270 |

.315 |

61 |

.130 |

.256 |

1 |

-0.6 |

.263 |

66 |

25 |

| Ryan McCarty |

419 |

.204 |

.274 |

.312 |

62 |

.108 |

.282 |

-2 |

-0.6 |

.262 |

64 |

35 |

| Yohendrick Pinango |

514 |

.223 |

.290 |

.353 |

77 |

.130 |

.271 |

-2 |

-0.6 |

.283 |

81 |

50 |

| Tucker Toman |

445 |

.201 |

.263 |

.285 |

52 |

.084 |

.291 |

2 |

-0.8 |

.246 |

56 |

31 |

| Eddinson Paulino |

407 |

.197 |

.253 |

.324 |

58 |

.127 |

.257 |

-2 |

-0.8 |

.254 |

64 |

34 |

| Alex De Jesus |

364 |

.199 |

.266 |

.296 |

55 |

.097 |

.303 |

-2 |

-0.9 |

.252 |

59 |

28 |

| Jacob Sharp |

242 |

.180 |

.254 |

.253 |

41 |

.073 |

.238 |

-4 |

-0.9 |

.233 |

46 |

15 |

| Jay Harry |

391 |

.193 |

.256 |

.293 |

51 |

.100 |

.244 |

-2 |

-0.9 |

.245 |

57 |

29 |

| Je’Von Ward |

391 |

.196 |

.289 |

.319 |

68 |

.123 |

.284 |

-2 |

-0.9 |

.272 |

71 |

33 |

| Nicolas Deschamps |

164 |

.154 |

.247 |

.238 |

35 |

.084 |

.286 |

-4 |

-0.9 |

.225 |

38 |

9 |

| J.R. Freethy |

361 |

.195 |

.299 |

.288 |

64 |

.093 |

.269 |

-9 |

-1.0 |

.270 |

66 |

29 |

| Jacob Wetzel |

314 |

.186 |

.268 |

.311 |

60 |

.125 |

.251 |

-1 |

-1.0 |

.258 |

62 |

25 |

| Peyton Williams |

352 |

.198 |

.259 |

.325 |

60 |

.127 |

.281 |

2 |

-1.0 |

.257 |

65 |

27 |

| Gabriel Martinez |

386 |

.209 |

.259 |

.295 |

53 |

.086 |

.259 |

3 |

-1.2 |

.247 |

57 |

28 |

| Hedbert Perez |

338 |

.175 |

.249 |

.315 |

57 |

.140 |

.250 |

0 |

-1.2 |

.248 |

61 |

26 |

| Jackson Hornung |

423 |

.214 |

.274 |

.326 |

65 |

.112 |

.332 |

-3 |

-1.3 |

.265 |

68 |

35 |

| Carter Cunningham |

405 |

.177 |

.269 |

.318 |

62 |

.141 |

.282 |

-2 |

-1.4 |

.263 |

68 |

33 |

| Sam Shaw |

317 |

.183 |

.265 |

.296 |

55 |

.113 |

.236 |

-9 |

-1.4 |

.251 |

61 |

23 |

| Peyton Powell |

302 |

.190 |

.270 |

.227 |

40 |

.037 |

.299 |

-2 |

-2.0 |

.232 |

41 |

18 |

Batters – Top Near-Age Offensive Comps

Batters – 80th/20th Percentiles

| Player |

80th BA |

80th OBP |

80th SLG |

80th OPS+ |

80th WAR |

20th BA |

20th OBP |

20th SLG |

20th OPS+ |

20th WAR |

| Vladimir Guerrero Jr. |

.317 |

.402 |

.567 |

160 |

5.7 |

.267 |

.351 |

.462 |

123 |

2.5 |

| Alejandro Kirk |

.299 |

.375 |

.462 |

128 |

5.2 |

.244 |

.319 |

.366 |

89 |

2.9 |

| Bo Bichette |

.319 |

.366 |

.512 |

138 |

4.9 |

.264 |

.310 |

.418 |

98 |

1.9 |

| Andrés Giménez |

.274 |

.340 |

.423 |

108 |

3.8 |

.221 |

.288 |

.328 |

72 |

1.5 |

| Kazuma Okamoto |

.275 |

.363 |

.533 |

141 |

3.9 |

.224 |

.311 |

.402 |

95 |

1.1 |

| Daulton Varsho |

.251 |

.315 |

.523 |

124 |

3.7 |

.202 |

.267 |

.401 |

83 |

1.4 |

| Ernie Clement |

.297 |

.327 |

.432 |

107 |

3.3 |

.242 |

.278 |

.351 |

73 |

1.1 |

| George Springer |

.279 |

.366 |

.495 |

134 |

3.3 |

.233 |

.322 |

.392 |

98 |

0.9 |

| Davis Schneider |

.243 |

.353 |

.485 |

127 |

3.1 |

.196 |

.306 |

.371 |

89 |

1.1 |

| Addison Barger |

.271 |

.341 |

.494 |

125 |

3.2 |

.222 |

.287 |

.389 |

86 |

0.6 |

| Nathan Lukes |

.299 |

.360 |

.452 |

122 |

2.8 |

.237 |

.304 |

.358 |

84 |

0.8 |

| Joey Loperfido |

.274 |

.335 |

.455 |

113 |

2.5 |

.221 |

.283 |

.354 |

75 |

0.3 |

| RJ Schreck |

.243 |

.353 |

.465 |

121 |

2.3 |

.189 |

.302 |

.344 |

80 |

0.4 |

| Anthony Santander |

.254 |

.335 |

.514 |

127 |

2.5 |

.204 |

.285 |

.399 |

87 |

0.0 |

| Jonatan Clase |

.243 |

.316 |

.409 |

97 |

2.2 |

.198 |

.270 |

.324 |

67 |

0.2 |

| Leo Jiménez |

.247 |

.343 |

.393 |

100 |

1.7 |

.200 |

.296 |

.307 |

68 |

0.3 |

| Myles Straw |

.263 |

.323 |

.366 |

90 |

1.9 |

.212 |

.271 |

.290 |

56 |

0.1 |

| Charles McAdoo |

.252 |

.315 |

.425 |

102 |

2.1 |

.198 |

.264 |

.327 |

63 |

-0.3 |

| Tyler Heineman |

.252 |

.341 |

.372 |

95 |

1.3 |

.191 |

.285 |

.279 |

57 |

0.4 |

| Carlos Mendoza |

.262 |

.356 |

.361 |

98 |

1.8 |

.209 |

.302 |

.288 |

66 |

0.0 |

| Brandon Valenzuela |

.236 |

.300 |

.397 |

89 |

1.9 |

.182 |

.238 |

.297 |

49 |

-0.3 |

| Ty France |

.275 |

.345 |

.429 |

112 |

1.9 |

.221 |

.294 |

.330 |

74 |

-0.5 |

| Rodolfo Castro |

.240 |

.311 |

.421 |

98 |

1.5 |

.191 |

.263 |

.318 |

61 |

-0.7 |

| Nick Goodwin |

.236 |

.314 |

.382 |

89 |

1.2 |

.181 |

.264 |

.284 |

53 |

-0.5 |

| Adrian Pinto |

.240 |

.309 |

.416 |

96 |

0.5 |

.186 |

.258 |

.303 |

55 |

-0.1 |

| Riley Tirotta |

.246 |

.324 |

.415 |

100 |

1.1 |

.194 |

.273 |

.314 |

61 |

-0.9 |

| Isiah Kiner-Falefa |

.273 |

.318 |

.361 |

87 |

1.1 |

.218 |

.266 |

.288 |

54 |

-0.8 |

| Ismael Munguia |

.269 |

.334 |

.377 |

95 |

0.9 |

.215 |

.284 |

.298 |

61 |

-0.7 |

| Arjun Nimmala |

.223 |

.284 |

.385 |

82 |

1.4 |

.174 |

.232 |

.285 |

44 |

-1.2 |

| Victor Arias |

.252 |

.318 |

.390 |

94 |

1.0 |

.205 |

.272 |

.311 |

63 |

-0.9 |

| Cutter Coffey |

.233 |

.299 |

.383 |

83 |

1.0 |

.182 |

.243 |

.288 |

48 |

-1.0 |

| Devonte Brown |

.225 |

.316 |

.378 |

87 |

0.7 |

.169 |

.262 |

.277 |

50 |

-1.0 |

| Sean Keys |

.208 |

.309 |

.390 |

90 |

1.1 |

.161 |

.258 |

.294 |

53 |

-1.2 |

| Aaron Parker |

.231 |

.288 |

.407 |

86 |

0.6 |

.173 |

.228 |

.296 |

45 |

-0.9 |

| Eloy Jiménez |

.270 |

.324 |

.430 |

104 |

0.7 |

.215 |

.270 |

.327 |

65 |

-1.0 |

| Josh Kasevich |

.258 |

.318 |

.320 |

75 |

0.5 |

.206 |

.267 |

.251 |

44 |

-1.1 |

| Joshua Rivera |

.221 |

.294 |

.320 |

67 |

0.6 |

.166 |

.241 |

.232 |

33 |

-1.0 |

| Geovanny Planchart |

.210 |

.297 |

.295 |

64 |

0.3 |

.156 |

.239 |

.218 |

29 |

-0.8 |

| Eddie Micheletti Jr. |

.218 |

.317 |

.381 |

90 |

0.7 |

.168 |

.269 |

.284 |

55 |

-1.3 |

| Phil Clarke |

.260 |

.347 |

.349 |

92 |

0.3 |

.197 |

.285 |

.265 |

53 |

-1.0 |

| Edward Duran |

.245 |

.306 |

.359 |

83 |

0.9 |

.181 |

.246 |

.262 |

43 |

-1.3 |

| Jorge Burgos |

.228 |

.291 |

.425 |

94 |

0.7 |

.179 |

.240 |

.327 |

57 |

-1.1 |

| Jace Bohrofen |

.212 |

.299 |

.387 |

87 |

0.5 |

.160 |

.244 |

.287 |

48 |

-1.4 |

| Rainer Nunez |

.262 |

.310 |

.409 |

93 |

0.4 |

.212 |

.259 |

.319 |

59 |

-1.4 |

| Alexis Hernandez |

.242 |

.309 |

.374 |

86 |

0.2 |

.186 |

.255 |

.281 |

50 |

-1.2 |

| Brennan Orf |

.210 |

.323 |

.341 |

82 |

0.0 |

.155 |

.267 |

.244 |

44 |

-0.9 |

| Cade Doughty |

.244 |

.290 |

.362 |

80 |

0.4 |

.195 |

.241 |

.286 |

46 |

-1.3 |

| Damiano Palmegiani |

.220 |

.304 |

.390 |

90 |

0.6 |

.168 |

.252 |

.298 |

52 |

-1.5 |

| Robert Brooks |

.199 |

.273 |

.320 |

61 |

-0.1 |

.139 |

.206 |

.215 |

16 |

-1.0 |

| Bryce Arnold |

.211 |

.298 |

.357 |

77 |

0.0 |

.164 |

.245 |

.273 |

46 |

-1.2 |

| Ryan McCarty |

.233 |

.304 |

.362 |

83 |

0.5 |

.181 |

.249 |

.274 |

45 |

-1.4 |

| Yohendrick Pinango |

.247 |

.315 |

.395 |

95 |

0.6 |

.195 |

.265 |

.309 |

61 |

-1.6 |

| Tucker Toman |

.231 |

.289 |

.329 |

70 |

0.3 |

.177 |

.234 |

.247 |

37 |

-1.7 |

| Eddinson Paulino |

.221 |

.276 |

.383 |

79 |

0.3 |

.175 |

.228 |

.282 |

41 |

-1.6 |

| Alex De Jesus |

.227 |

.296 |

.349 |

77 |

0.1 |

.172 |

.241 |

.253 |

38 |

-1.7 |

| Jacob Sharp |

.206 |

.284 |

.294 |

59 |

-0.4 |

.153 |

.230 |

.214 |

24 |

-1.5 |

| Jay Harry |

.218 |

.283 |

.346 |

71 |

0.1 |

.165 |

.228 |

.256 |

35 |

-1.6 |

| Je’Von Ward |

.222 |

.318 |

.373 |

90 |

0.1 |

.167 |

.261 |

.274 |

49 |

-1.8 |

| Nicolas Deschamps |

.186 |

.281 |

.286 |

57 |

-0.5 |

.126 |

.221 |

.190 |

17 |

-1.3 |

| J.R. Freethy |

.224 |

.327 |

.336 |

84 |

-0.1 |

.173 |

.275 |

.250 |

48 |

-1.7 |

| Jacob Wetzel |

.211 |

.296 |

.358 |

79 |

-0.2 |

.160 |

.243 |

.266 |

42 |

-1.7 |

| Peyton Williams |

.222 |

.283 |

.372 |

80 |

-0.2 |

.174 |

.233 |

.280 |

44 |

-1.7 |

| Gabriel Martinez |

.232 |

.282 |

.337 |

70 |

-0.4 |

.182 |

.231 |

.254 |

36 |

-2.1 |

| Hedbert Perez |

.201 |

.279 |

.368 |

75 |

-0.4 |

.151 |

.224 |

.269 |

38 |

-2.0 |

| Jackson Hornung |

.242 |

.301 |

.371 |

84 |

-0.4 |

.187 |

.246 |

.285 |

47 |

-2.3 |

| Carter Cunningham |

.206 |

.302 |

.374 |

86 |

-0.2 |

.150 |

.243 |

.264 |

43 |

-2.4 |

| Sam Shaw |

.213 |

.297 |

.357 |

76 |

-0.5 |

.154 |

.238 |

.247 |

36 |

-2.2 |

| Peyton Powell |

.217 |

.301 |

.260 |

56 |

-1.4 |

.161 |

.242 |

.195 |

22 |

-2.7 |

Batters – Platoon Splits

| Player |

BA vs. L |

OBP vs. L |

SLG vs. L |

BA vs. R |

OBP vs. R |

SLG vs. R |

| Vladimir Guerrero Jr. |

.292 |

.387 |

.514 |

.290 |

.372 |

.512 |

| Alejandro Kirk |

.274 |

.357 |

.411 |

.269 |

.342 |

.412 |

| Bo Bichette |

.297 |

.351 |

.471 |

.291 |

.336 |

.454 |

| Andrés Giménez |

.248 |

.313 |

.368 |

.249 |

.316 |

.378 |

| Kazuma Okamoto |

.257 |

.349 |

.479 |

.248 |

.331 |

.455 |

| Daulton Varsho |

.236 |

.287 |

.434 |

.224 |

.291 |

.467 |

| Ernie Clement |

.274 |

.310 |

.415 |

.266 |

.297 |

.380 |

| George Springer |

.254 |

.351 |

.446 |

.257 |

.340 |

.443 |

| Davis Schneider |

.225 |

.337 |

.435 |

.221 |

.327 |

.413 |

| Addison Barger |

.240 |

.306 |

.409 |

.246 |

.317 |

.457 |

| Nathan Lukes |

.250 |

.309 |

.355 |

.278 |

.345 |

.432 |

| Joey Loperfido |

.246 |

.308 |

.390 |

.245 |

.309 |

.415 |

| RJ Schreck |

.208 |

.315 |

.385 |

.220 |

.331 |

.413 |

| Anthony Santander |

.233 |

.318 |

.459 |

.226 |

.305 |

.453 |

| Jonatan Clase |

.224 |

.291 |

.371 |

.223 |

.295 |

.365 |

| Leo Jiménez |

.230 |

.322 |

.370 |

.221 |

.318 |

.333 |

| Myles Straw |

.241 |

.299 |

.328 |

.234 |

.293 |

.325 |

| Charles McAdoo |

.235 |

.301 |

.409 |

.224 |

.283 |

.366 |

| Tyler Heineman |

.220 |

.304 |

.320 |

.224 |

.317 |

.327 |

| Carlos Mendoza |

.233 |

.328 |

.311 |

.239 |

.332 |

.327 |

| Brandon Valenzuela |

.209 |

.277 |

.336 |

.202 |

.270 |

.344 |

| Ty France |

.246 |

.314 |

.384 |

.248 |

.320 |

.373 |

| Rodolfo Castro |

.221 |

.287 |

.396 |

.212 |

.286 |

.356 |

| Nick Goodwin |

.212 |

.297 |

.354 |

.202 |

.285 |

.311 |

| Adrian Pinto |

.222 |

.300 |

.333 |

.206 |

.270 |

.368 |

| Riley Tirotta |

.225 |

.314 |

.383 |

.218 |

.295 |

.354 |

| Isiah Kiner-Falefa |

.244 |

.295 |

.328 |

.246 |

.288 |

.320 |

| Ismael Munguia |

.244 |

.310 |

.311 |

.241 |

.306 |

.345 |

| Arjun Nimmala |

.204 |

.269 |

.345 |

.194 |

.256 |

.329 |

| Victor Arias |

.228 |

.288 |

.333 |

.231 |

.297 |

.353 |

| Cutter Coffey |

.207 |

.276 |

.333 |

.205 |

.269 |

.331 |

| Devonte Brown |

.204 |

.306 |

.344 |

.195 |

.282 |

.318 |

| Sean Keys |

.174 |

.268 |

.298 |

.190 |

.287 |

.347 |

| Aaron Parker |

.208 |

.265 |

.338 |

.199 |

.250 |

.345 |

| Eloy Jiménez |

.239 |

.304 |

.380 |

.243 |

.295 |

.370 |

| Josh Kasevich |

.237 |

.302 |

.298 |

.236 |

.289 |

.283 |

| Joshua Rivera |

.198 |

.274 |

.297 |

.192 |

.262 |

.273 |

| Geovanny Planchart |

.188 |

.269 |

.261 |

.179 |

.261 |

.250 |

| Eddie Micheletti Jr. |

.183 |

.280 |

.312 |

.196 |

.298 |

.346 |

| Phil Clarke |

.212 |

.293 |

.288 |

.236 |

.328 |

.309 |

| Edward Duran |

.221 |

.288 |

.327 |

.207 |

.269 |

.292 |

| Jorge Burgos |

.190 |

.259 |

.333 |

.204 |

.265 |

.387 |

| Jace Bohrofen |

.186 |

.269 |

.340 |

.191 |

.275 |

.348 |

| Rainer Nunez |

.250 |

.305 |

.383 |

.233 |

.279 |

.344 |

| Alexis Hernandez |

.222 |

.292 |

.333 |

.209 |

.277 |

.321 |

| Brennan Orf |

.167 |

.271 |

.238 |

.185 |

.302 |

.306 |

| Cade Doughty |

.221 |

.270 |

.336 |

.217 |

.265 |

.312 |

| Damiano Palmegiani |

.197 |

.290 |

.362 |

.189 |

.271 |

.332 |

| Robert Brooks |

.190 |

.261 |

.286 |

.158 |

.229 |

.253 |

| Bryce Arnold |

.188 |

.275 |

.300 |

.184 |

.268 |

.320 |

| Ryan McCarty |

.205 |

.280 |

.321 |

.203 |

.272 |

.308 |

| Yohendrick Pinango |

.218 |

.275 |

.333 |

.225 |

.297 |

.363 |

| Tucker Toman |

.198 |

.259 |

.264 |

.203 |

.264 |

.292 |

| Eddinson Paulino |

.186 |

.243 |

.275 |

.201 |

.257 |

.343 |

| Alex De Jesus |

.212 |

.288 |

.322 |

.192 |

.254 |

.282 |

| Jacob Sharp |

.179 |

.257 |

.254 |

.180 |

.253 |

.253 |

| Jay Harry |

.186 |

.245 |

.278 |

.195 |

.260 |

.299 |

| Je’Von Ward |

.186 |

.266 |

.309 |

.200 |

.298 |

.322 |

| Nicolas Deschamps |

.150 |

.244 |

.175 |

.155 |

.248 |

.262 |

| J.R. Freethy |

.200 |

.301 |

.300 |

.193 |

.298 |

.283 |

| Jacob Wetzel |

.179 |

.258 |

.310 |

.189 |

.273 |

.311 |

| Peyton Williams |

.189 |

.245 |

.289 |

.202 |

.264 |

.339 |

| Gabriel Martinez |

.219 |

.274 |

.316 |

.204 |

.252 |

.286 |

| Hedbert Perez |

.167 |

.235 |

.278 |

.179 |

.254 |

.330 |

| Jackson Hornung |

.215 |

.278 |

.322 |

.214 |

.272 |

.327 |

| Carter Cunningham |

.170 |

.255 |

.309 |

.180 |

.274 |

.322 |

| Sam Shaw |

.176 |

.256 |

.243 |

.186 |

.268 |

.314 |

| Peyton Powell |

.179 |

.247 |

.192 |

.194 |

.279 |

.241 |

Pitchers – Advanced

| Player |

IP |

K/9 |

BB/9 |

HR/9 |

BB% |

K% |

BABIP |

ERA+ |

3ERA+ |

FIP |

ERA- |

WAR |

| Dylan Cease |

164.7 |

10.5 |

3.5 |

1.0 |

9.2% |

27.7% |

.286 |

118 |

116 |

3.57 |

85 |

2.9 |

| Kevin Gausman |

162.3 |

8.7 |

2.6 |

1.2 |

6.8% |

23.2% |

.291 |

113 |

106 |

3.80 |

88 |

2.5 |

| Chris Bassitt |

151.0 |

8.2 |

3.2 |

1.2 |

8.2% |

21.4% |

.293 |

105 |

96 |

4.33 |

95 |

1.8 |

| Louis Varland |

108.7 |

8.6 |

2.5 |

1.1 |

6.7% |

23.2% |

.287 |

117 |

117 |

3.74 |

86 |

1.7 |

| Shane Bieber |

103.3 |

8.1 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

5.6% |

21.7% |

.286 |

116 |

112 |

3.75 |

86 |

1.7 |

| Trey Yesavage |

109.0 |

9.6 |

3.9 |

1.0 |

10.2% |

25.2% |

.274 |

110 |

114 |

3.81 |

91 |

1.7 |

| Cody Ponce |

128.7 |

8.9 |

2.8 |

1.3 |

7.4% |

23.5% |

.288 |

101 |

98 |

4.16 |

99 |

1.5 |

| Eric Lauer |

108.0 |

8.1 |

3.0 |

1.4 |

7.9% |

21.3% |

.282 |

100 |

98 |

4.50 |

100 |

1.1 |

| Max Scherzer |

95.7 |

8.7 |

2.4 |

1.6 |

6.5% |

23.3% |

.280 |

100 |

96 |

4.47 |

100 |

1.0 |

| José Berríos |

123.7 |

7.1 |

2.8 |

1.5 |

7.2% |

18.4% |

.286 |

94 |

92 |

4.79 |

106 |

1.0 |

| Josh Winckowski |

81.7 |

7.4 |

2.8 |

1.1 |

7.2% |

19.3% |

.295 |

104 |

106 |

4.14 |

96 |

0.8 |

| Jeff Hoffman |

61.3 |

10.9 |

3.4 |

1.2 |

9.1% |

29.1% |

.269 |

126 |

117 |

3.77 |

79 |

0.8 |

| Grant Rogers |

128.0 |

5.4 |

2.4 |

1.3 |

6.2% |

14.0% |

.288 |

89 |

92 |

4.80 |

112 |

0.7 |

| Angel Bastardo |

77.0 |

8.1 |

4.1 |

1.3 |

10.2% |

20.1% |

.291 |

96 |

102 |

4.71 |

104 |

0.7 |

| Robinson Piña |

82.0 |

6.9 |

3.0 |

1.3 |

7.6% |

17.7% |

.289 |

94 |

97 |

4.74 |

106 |

0.6 |

| CJ Van Eyk |

104.3 |

6.1 |

3.3 |

1.2 |

8.3% |

15.6% |

.289 |

90 |

92 |

4.87 |

112 |

0.6 |

| Tyler Rogers |

65.3 |

6.1 |

2.2 |

1.0 |

5.9% |

16.3% |

.276 |

114 |

108 |

4.08 |

87 |

0.6 |

| Trenton Wallace |

70.3 |

8.4 |

4.4 |

1.3 |

11.1% |

21.5% |

.282 |

95 |

98 |

4.80 |

105 |

0.5 |

| Lazaro Estrada |

88.7 |

7.7 |

2.8 |

1.4 |

7.3% |

19.8% |

.290 |

91 |

94 |

4.62 |

110 |

0.5 |

| Braydon Fisher |

60.7 |

10.5 |

4.3 |

1.0 |

11.1% |

27.1% |

.282 |

115 |

120 |

3.91 |

87 |

0.5 |

| Fernando Perez |

105.0 |

6.1 |

2.7 |

1.4 |

6.9% |

15.7% |

.285 |

89 |

94 |

4.79 |

113 |

0.5 |

| Ryan Burr |

36.3 |

10.2 |

3.2 |

1.0 |

8.5% |

26.8% |

.298 |

123 |

116 |

3.41 |

82 |

0.5 |

| Michael Plassmeyer |

89.0 |

7.2 |

2.6 |

1.4 |

6.9% |

18.7% |

.287 |

89 |

91 |

4.79 |

112 |

0.4 |

| Seranthony Domínguez |

57.0 |

10.4 |

4.3 |

1.3 |

10.9% |

26.7% |

.273 |

112 |

110 |

4.20 |

89 |

0.4 |

| Yariel Rodríguez |

74.0 |

8.6 |

4.3 |

1.2 |

11.0% |

22.4% |

.270 |

100 |

99 |

4.62 |

100 |

0.4 |

| Tommy Nance |

49.7 |

8.7 |

2.7 |

1.1 |

7.1% |

22.6% |

.300 |

112 |

104 |

3.89 |

89 |

0.4 |

| Brendon Little |

62.3 |

10.0 |

5.1 |

0.9 |

12.6% |

24.8% |

.288 |

113 |

112 |

4.03 |

88 |

0.4 |

| Adam Macko |

75.7 |

7.8 |

3.9 |

1.3 |

9.9% |

19.8% |

.284 |

89 |

94 |

4.89 |

112 |

0.4 |

| Jake Bloss |

69.7 |

7.0 |

3.9 |

1.4 |

9.7% |

17.4% |

.289 |

89 |

95 |

5.00 |

112 |

0.4 |

| Chase Lee |

60.3 |

9.0 |

2.7 |

1.2 |

7.1% |

23.8% |

.287 |

110 |

109 |

3.99 |

91 |

0.4 |

| Mason Fluharty |

61.3 |

9.7 |

3.7 |

1.2 |

9.7% |

25.5% |

.278 |

107 |

114 |

4.13 |

93 |

0.3 |

| Easton Lucas |

74.0 |

8.0 |

3.8 |

1.2 |

9.6% |

20.4% |

.291 |

90 |

91 |

4.51 |

111 |

0.3 |

| Bowden Francis |

76.7 |

7.9 |

3.1 |

1.6 |

8.0% |

20.6% |

.269 |

91 |

89 |

5.04 |

110 |

0.3 |

| Anders Tolhurst |

65.3 |

7.0 |

3.2 |

1.4 |

8.1% |

18.0% |

.286 |

88 |

93 |

4.79 |

113 |

0.3 |

| Alex Amalfi |

70.3 |

8.1 |

4.4 |

1.3 |

10.9% |

20.1% |

.289 |

92 |

97 |

4.80 |

108 |

0.2 |

| Pat Gallagher |

68.0 |

7.1 |

3.3 |

1.3 |

8.4% |

18.1% |

.289 |

92 |

94 |

4.72 |

109 |

0.2 |

| Yimi García |

39.7 |

9.5 |

3.4 |

1.1 |

9.0% |

25.3% |

.282 |

104 |

96 |

4.05 |

96 |

0.2 |

| Rafael Sanchez |

86.0 |

5.8 |

2.8 |

1.5 |

7.1% |

14.5% |

.297 |

85 |

89 |

4.98 |

118 |

0.2 |

| Nic Enright |

37.3 |

8.2 |

3.1 |

1.2 |

8.2% |

21.5% |

.286 |

104 |

105 |

4.21 |

96 |

0.1 |

| Ryan Borucki |

37.0 |

9.0 |

4.1 |

1.2 |

10.6% |

23.0% |

.283 |

103 |

100 |

4.62 |

97 |

0.1 |

| Ryan Jennings |

53.7 |

9.1 |

4.0 |

1.3 |

10.1% |

22.8% |

.290 |

94 |

96 |

4.77 |

106 |

0.1 |

| Nick Sandlin |

46.7 |

9.3 |

4.2 |

1.3 |

11.1% |

24.1% |

.264 |

100 |

102 |

4.66 |

100 |

0.1 |

| Joe Mantiply |

40.0 |

7.4 |

2.3 |

1.1 |

5.8% |

19.3% |

.306 |

99 |

92 |

3.96 |

101 |

0.1 |

| Hayden Juenger |

56.7 |

7.6 |

3.8 |

1.1 |

9.8% |

19.5% |

.285 |

96 |

99 |

4.50 |

104 |

0.1 |

| Nate Garkow |

44.3 |

9.1 |

4.1 |

1.2 |

10.5% |

23.7% |

.280 |

100 |

101 |

4.38 |

100 |

0.0 |

| Yondrei Rojas |

41.7 |

8.4 |

3.5 |

1.3 |

8.8% |

21.5% |

.284 |

98 |

105 |

4.60 |

102 |

0.0 |

| Dillon Tate |

45.0 |

7.4 |

3.8 |

1.0 |

9.7% |

18.9% |

.286 |

97 |

93 |

4.56 |

103 |

0.0 |

| Ryan Watson |

80.3 |

5.5 |

2.8 |

1.5 |

7.2% |

14.1% |

.286 |

83 |

84 |

5.13 |

121 |

0.0 |

| Eric Pardinho |

38.3 |

8.5 |

4.7 |

1.2 |

11.5% |

20.7% |

.296 |

95 |

99 |

4.62 |

105 |

0.0 |

| Tanner Andrews |

38.0 |

7.8 |

3.8 |

1.2 |

9.5% |

19.6% |

.297 |

94 |

93 |

4.48 |

106 |

-0.1 |

| Jorge Alcala |

53.3 |

9.6 |

4.1 |

1.5 |

10.3% |

24.6% |

.283 |

93 |

93 |

4.68 |

107 |

-0.1 |

| Ryan Boyer |

47.3 |

7.6 |

3.0 |

1.3 |

7.8% |

19.6% |

.285 |

93 |

93 |

4.73 |

108 |

-0.1 |

| Erik Swanson |

44.0 |

8.2 |

3.5 |

1.4 |

8.9% |

21.1% |

.288 |

94 |

93 |

4.64 |

106 |

-0.1 |

| Devereaux Harrison |

89.3 |

6.9 |

4.5 |

1.5 |

11.1% |

16.8% |

.290 |

81 |

86 |

5.40 |

123 |

-0.1 |

| Michael Dominguez |

62.7 |

7.6 |

5.2 |

1.6 |

12.7% |

18.7% |

.282 |

80 |

85 |

5.67 |

125 |

-0.1 |

| Kevin Gowdy |

38.0 |

6.4 |

4.3 |

1.2 |

10.5% |

15.7% |

.288 |

90 |

90 |

5.19 |

111 |

-0.2 |

| Chad Green |

38.3 |

7.5 |

3.1 |

1.6 |

7.9% |

19.4% |

.292 |

91 |

84 |

4.96 |

110 |

-0.2 |

| Jacob Barnes |

36.7 |

6.4 |

3.7 |

1.2 |

9.3% |

16.0% |

.296 |

87 |

79 |

4.83 |

115 |

-0.2 |

| Bobby Milacki |

61.3 |

5.4 |

3.2 |

1.5 |

8.1% |

13.7% |

.286 |

83 |

84 |

5.35 |

120 |

-0.2 |

| Grayson Thurman |

37.0 |

6.8 |

4.1 |

1.5 |

10.1% |

16.7% |

.292 |

87 |

90 |

5.22 |

114 |

-0.2 |

| Chay Yeager |

48.0 |

7.7 |

4.1 |

1.3 |

10.4% |

19.3% |

.283 |

87 |

93 |

4.98 |

115 |

-0.2 |

| Jimmy Burnette |

35.7 |

8.6 |

5.3 |

1.0 |

13.1% |

21.3% |

.283 |

89 |

90 |

4.99 |

113 |

-0.2 |

| Geison Urbaez |

50.0 |

5.4 |

4.7 |

1.3 |

11.3% |

13.0% |

.288 |

79 |

82 |

5.64 |

127 |

-0.3 |

| Hunter Gregory |

54.0 |

7.5 |

4.5 |

1.3 |

11.2% |

18.6% |

.289 |

82 |

86 |

5.14 |

122 |

-0.3 |

| Johnathan Lavallee |

34.0 |

7.7 |

5.3 |

1.3 |

12.7% |

18.5% |

.283 |

85 |

88 |

5.22 |

118 |

-0.3 |

| Travis Kuhn |

49.0 |

6.2 |

4.4 |

1.1 |

11.0% |

15.6% |

.283 |

86 |

86 |

5.20 |

117 |

-0.3 |

| Conor Larkin |

39.0 |

7.4 |

4.6 |

1.4 |

11.4% |

18.2% |

.281 |

84 |

86 |

5.29 |

119 |

-0.4 |

| Justin Kelly |

36.7 |

5.6 |

3.7 |

1.5 |

9.1% |

13.9% |

.288 |

82 |

85 |

5.43 |

122 |

-0.4 |

Pitchers – Top Near-Age Comps

Pitchers – Splits and Percentiles

| Player |

BA vs. L |

OBP vs. L |

SLG vs. L |

BA vs. R |

OBP vs. R |

SLG vs. R |

80th WAR |

20th WAR |

80th ERA |

20th ERA |

| Dylan Cease |

.229 |

.310 |

.386 |

.210 |

.279 |

.343 |

4.0 |

1.3 |

3.04 |

4.42 |

| Kevin Gausman |

.229 |

.287 |

.382 |

.254 |

.300 |

.416 |

3.6 |

1.4 |

3.17 |

4.39 |

| Chris Bassitt |

.253 |

.333 |

.449 |

.243 |

.307 |

.372 |

2.8 |

0.8 |

3.44 |

4.79 |

| Louis Varland |

.239 |

.294 |

.388 |

.234 |

.290 |

.381 |

2.5 |

0.8 |

3.10 |

4.37 |

| Shane Bieber |

.243 |

.294 |

.402 |

.243 |

.281 |

.395 |

2.4 |

1.0 |

3.13 |

4.31 |

| Trey Yesavage |

.206 |

.300 |

.332 |

.232 |

.303 |

.391 |

2.4 |

0.5 |

3.39 |

4.72 |

| Cody Ponce |

.246 |

.310 |

.428 |

.237 |

.294 |

.397 |

2.3 |

0.5 |

3.64 |

4.86 |

| Eric Lauer |

.257 |

.319 |

.438 |

.243 |

.305 |

.425 |

1.8 |

0.2 |

3.70 |

4.99 |

| Max Scherzer |

.267 |

.333 |

.487 |

.222 |

.262 |

.398 |

1.7 |

0.3 |

3.59 |

5.12 |

| José Berríos |

.258 |

.330 |

.463 |

.258 |

.307 |

.430 |

1.6 |

0.1 |

4.07 |

5.15 |

| Josh Winckowski |

.260 |

.321 |

.413 |

.247 |

.300 |

.402 |

1.3 |

0.2 |

3.57 |

4.85 |

| Jeff Hoffman |

.206 |

.298 |

.355 |

.216 |

.292 |

.379 |

1.6 |

-0.1 |

2.47 |

4.68 |

| Grant Rogers |

.277 |

.341 |

.477 |

.259 |

.304 |

.404 |

1.3 |

-0.1 |

4.34 |

5.31 |

| Angel Bastardo |

.241 |

.327 |

.431 |

.253 |

.332 |

.410 |

1.2 |

0.1 |

3.93 |

5.00 |

| Robinson Piña |

.270 |

.341 |

.474 |

.247 |

.307 |

.397 |

1.2 |

0.0 |

3.94 |

5.13 |

| CJ Van Eyk |

.263 |

.333 |

.415 |

.259 |

.332 |

.434 |

1.1 |

-0.1 |

4.29 |

5.25 |

| Tyler Rogers |

.254 |

.306 |

.395 |

.248 |

.297 |

.387 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

3.14 |

4.58 |

| Trenton Wallace |

.212 |

.306 |

.353 |

.253 |

.346 |

.430 |

1.0 |

-0.1 |

3.89 |

5.24 |

| Lazaro Estrada |

.244 |

.317 |

.415 |

.262 |

.314 |

.455 |

1.3 |

-0.1 |

3.99 |

5.30 |

| Braydon Fisher |

.208 |

.319 |

.337 |

.222 |

.303 |

.381 |

1.0 |

-0.2 |

3.07 |

4.56 |

| Fernando Perez |

.274 |

.339 |

.477 |

.252 |

.297 |

.410 |

1.0 |

-0.3 |

4.37 |

5.46 |

| Ryan Burr |

.238 |

.314 |

.413 |

.218 |

.271 |

.333 |

0.8 |

0.0 |

2.59 |

4.57 |

| Michael Plassmeyer |

.224 |

.288 |

.364 |

.269 |

.335 |

.469 |

1.0 |

-0.3 |

4.25 |

5.50 |

| Seranthony Domínguez |

.247 |

.342 |

.443 |

.195 |

.287 |

.336 |

1.1 |

-0.4 |

2.87 |

5.09 |

| Yariel Rodríguez |

.238 |

.349 |

.421 |

.227 |

.308 |

.373 |

1.0 |

-0.2 |

3.66 |

4.96 |

| Tommy Nance |

.222 |

.292 |

.383 |

.263 |

.320 |

.412 |

0.9 |

-0.1 |

2.95 |

4.97 |

| Brendon Little |

.195 |

.304 |

.264 |

.236 |

.341 |

.399 |

1.1 |

-0.4 |

3.04 |

4.75 |

| Adam Macko |

.247 |

.336 |

.441 |

.248 |

.335 |

.416 |

0.9 |

-0.2 |

4.26 |

5.37 |

| Jake Bloss |

.281 |

.354 |

.469 |

.238 |

.310 |

.411 |

0.8 |

-0.1 |

4.28 |

5.32 |

| Chase Lee |

.253 |

.337 |

.451 |

.225 |

.275 |

.359 |

0.9 |

-0.2 |

3.15 |

4.79 |

| Mason Fluharty |

.209 |

.284 |

.363 |

.234 |

.323 |

.390 |

0.8 |

-0.4 |

3.33 |

4.87 |

| Easton Lucas |

.234 |

.318 |

.340 |

.253 |

.326 |

.439 |

0.8 |

-0.3 |

4.23 |

5.49 |

| Bowden Francis |

.259 |

.335 |

.455 |

.232 |

.299 |

.430 |

0.8 |

-0.3 |

4.15 |

5.40 |

| Anders Tolhurst |

.250 |

.317 |

.461 |

.260 |

.324 |

.405 |

0.7 |

-0.2 |

4.22 |

5.38 |

| Alex Amalfi |

.258 |

.343 |

.450 |

.236 |

.324 |

.382 |

0.7 |

-0.3 |

4.15 |

5.20 |

| Pat Gallagher |

.262 |

.338 |

.413 |

.248 |

.308 |

.434 |

0.6 |

-0.4 |

4.13 |

5.39 |

| Yimi García |

.238 |

.333 |

.460 |

.218 |

.289 |

.333 |

0.6 |

-0.2 |

3.21 |

5.36 |

| Rafael Sanchez |

.265 |

.324 |

.419 |

.284 |

.329 |

.497 |

0.7 |

-0.3 |

4.54 |

5.55 |

| Nic Enright |

.246 |

.303 |

.393 |

.241 |

.312 |

.422 |

0.5 |

-0.3 |

3.45 |

5.03 |

| Ryan Borucki |

.188 |

.304 |

.271 |

.261 |

.349 |

.478 |

0.5 |

-0.3 |

3.44 |

5.11 |

| Ryan Jennings |

.247 |

.345 |

.412 |

.232 |

.320 |

.411 |

0.6 |

-0.4 |

3.83 |

5.35 |

| Nick Sandlin |

.240 |

.337 |

.440 |

.219 |

.315 |

.385 |

0.7 |

-0.4 |

3.48 |

5.23 |

| Joe Mantiply |

.233 |

.281 |

.333 |

.275 |

.318 |

.471 |

0.4 |

-0.2 |

3.55 |

5.28 |

| Hayden Juenger |

.223 |

.319 |

.359 |

.263 |

.328 |

.432 |

0.5 |

-0.3 |

3.96 |

5.03 |

| Nate Garkow |

.232 |

.323 |

.378 |

.233 |

.316 |

.419 |

0.4 |

-0.5 |

3.63 |

5.20 |

| Yondrei Rojas |

.225 |

.313 |

.366 |

.253 |

.330 |

.451 |

0.3 |

-0.3 |

3.68 |

4.88 |

| Dillon Tate |

.261 |

.370 |

.435 |

.238 |

.314 |

.371 |

0.3 |

-0.4 |

3.87 |

5.16 |

| Ryan Watson |

.281 |

.339 |

.477 |

.259 |

.316 |

.441 |

0.5 |

-0.5 |

4.63 |

5.68 |

| Eric Pardinho |

.264 |

.354 |

.389 |

.225 |

.315 |

.425 |

0.3 |

-0.3 |

3.96 |

4.98 |

| Tanner Andrews |

.262 |

.342 |

.431 |

.244 |

.313 |

.407 |

0.3 |

-0.4 |

3.81 |

5.39 |

| Jorge Alcala |

.242 |

.337 |

.462 |

.230 |

.307 |

.398 |

0.3 |

-0.7 |

3.89 |

5.68 |

| Ryan Boyer |

.267 |

.344 |

.442 |

.237 |

.312 |

.412 |

0.3 |

-0.5 |

3.82 |

5.34 |

| Erik Swanson |

.265 |

.337 |

.494 |

.239 |

.306 |

.386 |

0.3 |

-0.5 |

3.76 |

5.40 |

| Devereaux Harrison |

.278 |

.360 |

.477 |

.247 |

.332 |

.429 |

0.4 |

-0.8 |

4.78 |

5.92 |

| Michael Dominguez |

.270 |

.374 |

.505 |

.239 |

.340 |

.403 |

0.3 |

-0.7 |

4.75 |

6.06 |

| Kevin Gowdy |

.279 |

.380 |

.500 |

.238 |

.323 |

.357 |

0.1 |

-0.5 |

4.34 |

5.50 |

| Chad Green |

.269 |

.338 |

.493 |

.256 |

.309 |

.442 |

0.1 |

-0.6 |

4.00 |

5.77 |

| Jacob Barnes |

.258 |

.352 |

.419 |

.271 |

.323 |

.447 |

0.0 |

-0.6 |

4.28 |

5.89 |

| Bobby Milacki |

.250 |

.320 |

.411 |

.289 |

.353 |

.496 |

0.2 |

-0.6 |

4.62 |

5.78 |

| Grayson Thurman |

.279 |

.364 |

.471 |

.247 |

.319 |

.432 |

0.0 |

-0.5 |

4.30 |

5.51 |

| Chay Yeager |

.242 |

.343 |

.407 |

.250 |

.330 |

.427 |

0.1 |

-0.6 |

4.25 |

5.46 |

| Jimmy Burnette |

.204 |

.339 |

.306 |

.250 |

.368 |

.432 |

0.0 |

-0.6 |

4.19 |

5.55 |

| Geison Urbaez |

.250 |

.337 |

.466 |

.283 |

.383 |

.416 |

0.0 |

-0.7 |

4.88 |

6.00 |

| Hunter Gregory |

.248 |

.358 |

.386 |

.261 |

.336 |

.468 |

0.1 |

-0.7 |

4.59 |

5.94 |

| Johnathan Lavallee |

.266 |

.373 |

.422 |

.232 |

.325 |

.435 |

-0.1 |

-0.7 |

4.50 |

5.89 |

| Travis Kuhn |

.272 |

.362 |

.444 |

.243 |

.346 |

.387 |

0.0 |

-0.7 |

4.43 |

5.68 |

| Conor Larkin |

.265 |

.367 |

.485 |

.238 |

.330 |

.393 |

-0.1 |

-0.8 |

4.54 |

5.96 |

| Justin Kelly |

.258 |

.338 |

.439 |

.280 |

.348 |

.476 |

-0.2 |

-0.6 |

4.69 |

5.86 |

Players are listed with their most recent teams wherever possible. This includes players who are unsigned or have retired, players who will miss 2026 due to injury, and players who were released in 2025. So yes, if you see Joe Schmoe, who quit baseball back in August to form a Ambient Math-Rock Trip-Hop Yacht Metal band that only performs in abandoned malls, he’s still listed here intentionally. ZiPS is assuming a league with an ERA of 4.16.

Hitters are ranked by zWAR, which is to say, WAR values as calculated by me, Dan Szymborski, whose surname is spelled with a z. WAR values might differ slightly from those that appear in the full release of ZiPS. Finally, I will advise anyone against — and might karate chop anyone guilty of — merely adding up WAR totals on a depth chart to produce projected team WAR. It is important to remember that ZiPS is agnostic about playing time, and has no information about, for example, how quickly a team will call up a prospect or what veteran has fallen into disfavor.

As always, incorrect projections are either caused by misinformation, a non-pragmatic reality, or by the skillful sabotage of our friend and former editor. You can, however, still get mad at me on Twitter or on BlueSky. This last is, however, not an actual requirement.

![]() Sponsor Us on Patreon

Sponsor Us on Patreon![]() Give a Gift Subscription

Give a Gift Subscription![]() Email Us: podcast@fangraphs.com

Email Us: podcast@fangraphs.com![]() Effectively Wild Subreddit

Effectively Wild Subreddit![]() Effectively Wild Wiki

Effectively Wild Wiki![]() Apple Podcasts Feed

Apple Podcasts Feed ![]() Spotify Feed

Spotify Feed![]() YouTube Playlist

YouTube Playlist![]() Facebook Group

Facebook Group![]() Bluesky Account

Bluesky Account![]() Twitter Account

Twitter Account![]() Get Our Merch!

Get Our Merch!