Five Things I Liked (Or Didn’t Like) This Week, April 4

Welcome to this season’s first edition of Five Things I Liked (Or Didn’t Like) This Week. I’m never more excited to watch baseball than I am at the end of March. The winter feels endlessly long, even for me in pleasant San Francisco. Spring training doesn’t quite scratch the itch. A series in Tokyo? Eh, everyone was asleep. But then comes Opening Day, and suddenly there’s baseball everywhere. Hats at the grocery store. Announcers on television and on the radio. Crowds filling bars and stadiums, TVs broadcasting the soothing sounds of my favorite sport. I’m all fired up. You only get one opening week a year, and this one’s been excellent. So after the customary nod to Zach Lowe (now of The Ringer, congrats Zach) for the format, let’s get right to the things that made me jump out of my seat this week.

1. Mookie!

I’ll admit to being a little skeptical about how the start of Mookie Betts’s season would go. It’s not because of any doubt about his skill – at this point in his career, I think he’s earned the benefit of the doubt there. But we’re not talking about how Betts would look at full strength. In fact, the reason I was skeptical was because he’s specifically not at full strength after losing nearly 20 pounds during a bout with norovirus.

Betts doesn’t weigh a lot to begin with – he’s officially listed at 180 pounds, but he checked into spring training this year at 175, according to Dodgers announcer Joe Davis. Losing 20 pounds from there is a big deal. Betts hits for a ton of power given his stature, but reducing his body weight by more than 10% makes that an even greater challenge. When he missed the Dodgers’ two games in Tokyo and then came back to play on Opening Day while still clearly affected, I mentally marked down my expectations for him early on.

Betts still isn’t back to full strength. Per a Dodgers broadcast last week, he’s back up to 165 pounds, and still hoping to gain more weight sooner rather than later to deal with the rigors of the season. That lack of oomph shows in the batted ball data; it is, of course, very early in the season, but Betts has barreled up only a single ball, and the hardest he’s hit one all year was a mere 100.8 mph. (For context, his max exit velo last season was 109.4 mph.) His bat speed is down. It shows on Betts’s body, too; he’s always been slight, but he looks smaller this year, because he is.

One place it hasn’t showed up? His batting line. He’s hitting .300/.364/.750 to start the year, and that’s with a .188 BABIP. He has more home runs (three) than strikeouts (one). Every single one of those homers gave the Dodgers the lead. And every single one of them had juuuuuust enough power to clear the wall:

How much distance did those balls have to spare? Maybe 10 feet combined? I think we need to look into the possibility that Betts is a magical being unconstrained by the rules of reality. I don’t know how else to explain his incredible performance even as he’s so focused on recovery that he eats meals during games to try to regain muscle mass.

If you’ve followed his career, you know that Betts is prone to white-hot streaks where he hits everything out of the park. I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised. But doing it when he’s visibly weakened by illness? Doing it while playing shortstop full time? Doubt Betts at your own risk. The Dodgers are impressive in a million ways – but right now, I can’t stop watching Mookie and giggling with delight.

2. Follow the Bouncing Wall

Ever heard of a strike ‘em out, throw ‘em out single play? Jeremiah Estrada managed that trick over the weekend, and in a way I’ve never seen before:

It’s not unheard of for a pitcher to retrieve the ball after a dropped third strike. Here’s another from the first week of the season:

But that’s how they happen, with balls that bounce back toward the field of play, and bounce far enough that the catcher can’t reach them. After the ball gets behind the plate, it’s the catcher’s ball for better or worse. Unless you’re playing with the wall bumper settings turned up to maximum, that is:

The ball hit a solid railing perfectly, flush and angled back into the field of play. A fraction of an inch in any direction would have made it completely unplayable. But throw enough fastballs off the wall behind the plate, and apparently one will kick back perfectly for some pitcher fielding practice. I’ve never seen anything like it – and that feeling, that I’ve never seen anything like what just occurred, is exactly why I’m so happy to have regular-season baseball back in my life.

3. Genius Defenders and Oblivious Baserunners

If you played baseball or softball growing up, you probably have the same instincts as me: When you see a rundown, you get giddy. Maybe, like me, you even say “Ooh! Pickle!” before you even notice that you’re talking. At the youth level, turning a pickled runner into an out is anything but a sure thing, and both the defenders and the runner have a lot to say about how things go. In the big leagues, the defenders are just too good for that. Escaping a rundown is getting tougher every year, because with perfect execution by both the runner and the defense, the runner is always out.

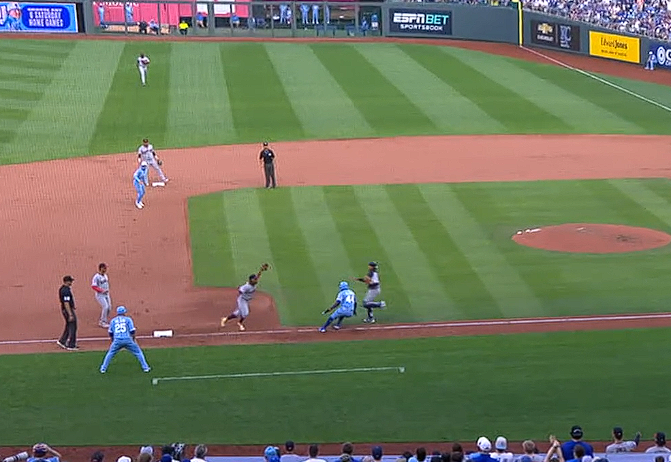

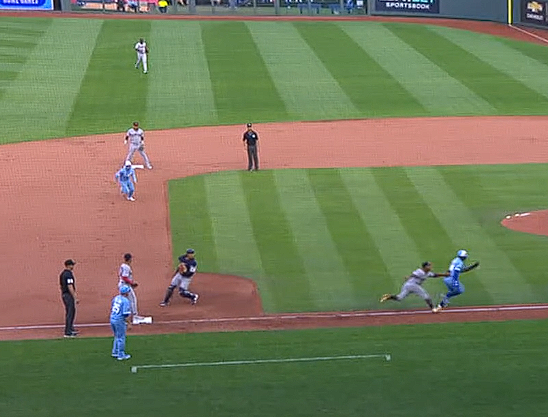

Here’s a classic one for you, a grounder to third base that hung Dairon Blanco out to dry on the basepaths:

You can quibble with having Blanco run on contact there, with no outs and Bobby Witt Jr. on deck. After the ball was in play, though, he didn’t have a lot of options. Catcher Bo Naylor came up the line aggressively and gave Blanco nowhere to hide. So Blanco went for the classic “break toward the thrower after he releases” plan; he didn’t execute it perfectly, but even if he did, it probably wouldn’t have worked. José Ramírez is fast, Hunter Gaddis and Carlos Santana were both covering home plate for reinforcements if the rundown continued, and like I said, it’s nearly impossible to escape a rundown conducted by major league fielders.

Why am I showing you this standard play? Because it wasn’t a standard play, and didn’t end there. Ramírez wasn’t just bluffing to third with that post-tag pivot:

It’s fun to watch a baseball genius at work. Ramírez made a string of great decisions on this play that equaled Kansas City’s string of bad ones. First, he took off down the third base line even before Naylor’s throw was in his glove. Blanco might be faster than him in a footrace, but he was already accelerating homeward when Blanco planted and changed direction. Rundowns are about quickness, not speed, and Ramírez is preternaturally agile.

He had the runner at second on his mind the entire time, too. You can see him waving Naylor toward him to hurry the play up. By the time he received the throw, he was already thinking about second base. Then, as he turned that way, he gave Kyle Isbel enough of a deke to freeze him on the basepaths. He even managed to re-insert himself into the rundown, though he wisely stepped aside when he saw his teammates had it under control.

Isbel, on the other hand, didn’t cover himself with glory. On this snapshot, the play should essentially be over:

Look at how far down the line Ramírez had already gotten, with Blanco still trying to change direction. That out was as good as made, Isbel had a perfect view of it, and he was close enough to second base to get back easily. But with the ball still right near third base and a fast and accelerating player holding it, Isbel inexplicably decided to take off:

Here’s how bad that decision was: Between Isbel deciding to run and Ramírez tagging Blanco out, Isbel took exactly two steps. He was maybe 20% of the way to third when Ramírez made the tag, and Ramírez was maybe 20% of the way from third to home.

Poor Jonathan India. He seems to know his way around a rundown. While the rest of the Royals were finding ways to create outs, he played everything perfectly. He tore down the line to first. When the defense abandoned him to cover the rundown, he went partway to second. And when Isbel got caught too, India did the right thing and went all the way to the second base bag. Just to put the cherry on top, rewatch the clip of Isbel getting tagged out. India didn’t step on the bag until the tag was applied. That’s because he was trying to start a rundown of his own; if Isbel had just sprinted back to second instead of stopping, India would have retreated to first, hopefully allowing Isbel to reach third or maybe even getting out of the rundown without being tagged given how many fielders were down near home plate. It’s amazing how good baseball players are at these little things. Well, how good they usually are, at least.

4. Lunging Practice

Double plays are a frequent feature of this column, because a well-turned double play, particularly if the degree of difficulty is high, is one of the most exciting plays in baseball. It features so many people operating in unison, there are usually close plays for at least one of the outs, and acrobatic pivots at second are just visually pleasing, period. And then you’ve got the double plays that aren’t perfect but are satisfying nonetheless:

What happened here? First, Mark Vientos made a difficult pick on a short hop. Then he judged that he had enough time and threw to second:

You can tell that something is wrong with the throw even in that abbreviated clip. The angle looks wrong, and so does his arm action. Good hands, yes, but bad throw:

Luisangel Acuña made that look easier than it was, but that could have been a disaster. His glove actually clipped second base as he went down for that one. How could it not, given the short hop? The ball rattled around in his glove, and he nearly lost his footing on the base while securing it, but he made the tough catch and even kept himself in position to throw to first.

At this point in the play, doubling up Isaac Paredes was far from automatic. Acuña didn’t have the time to baby the throw; he had to rip it and hope for reasonable accuracy. And “reasonable” is about what he got:

Pete Alonso isn’t a heralded defender, but he played this ball perfectly. When he saw the flight path, he went out and attacked the catch point. Stay back, and you have an in-between hop. Paredes might even beat out the throw; it was a really close play. But Alonso cut down the distance with his stretch, and he even got a bit of momentum by pushing on the base with his right foot, making sure to keep in contact until after he’d caught the ball. I love the brace with his right hand, too; that’s a good way to make sure that a collision with the ground doesn’t jar the ball out of the glove.

Honestly, that ball should be a double play every time without the need for anything spectacular. But hey, it was the first day of the season. Everyone was still getting up to game speed. And what better way to do that than by practicing some tough catches?

5. George Springer Still Has It

In the prime of his career, George Springer was a do-it-all outfielder in addition to being a slugger. He played 500 or so innings a year in center, spent the balance in right field, and showed off a cannon arm and fantastic instincts to go with plus speed. At 35, he’s not that kind of defender anymore. His last two seasons have been his worst defensive efforts as a major leaguer. But there’s a big difference between a diminished Springer and your regular kind of bad defender.

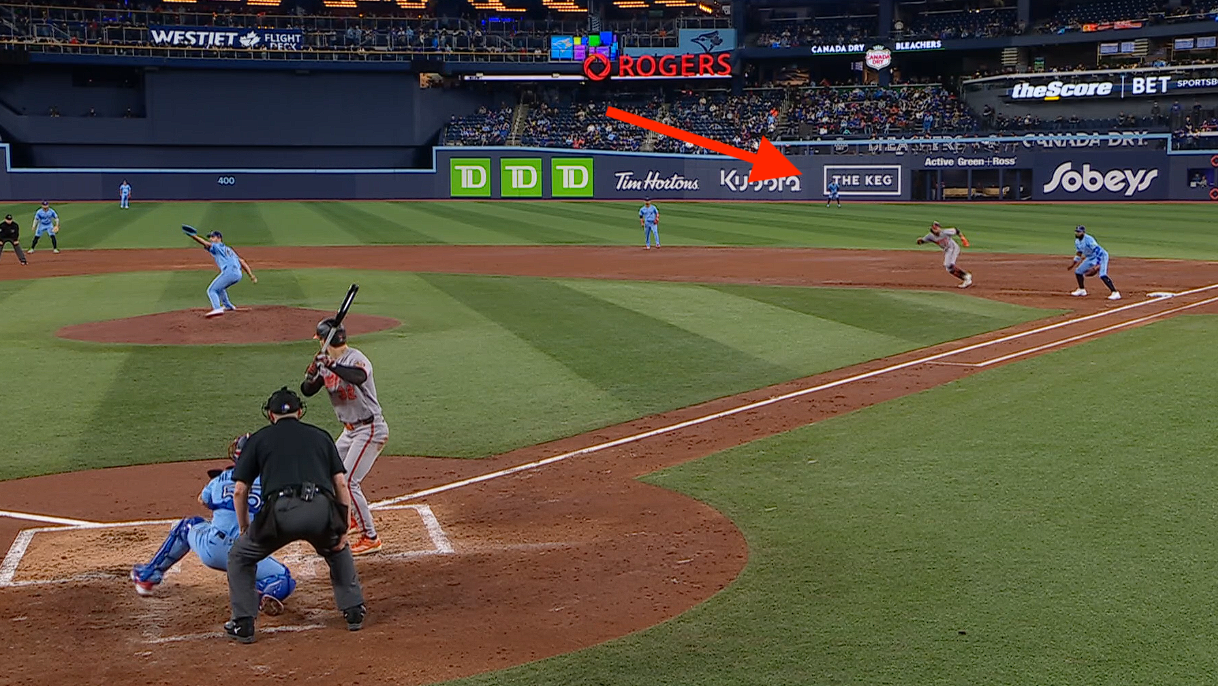

You can be a bad defender in many different ways. You can have bad instincts, or no speed, or a scattershot arm. But while Springer’s sprint speed is down, his heady play isn’t. How many below-average defenders can do this?

That’s not a great angle from the live broadcast, but I wanted to show it to you first so you can get an idea of how routine everything looked until the slide. Springer was playing far off the line in right when Ryan O’Hearn ripped the ball down the line, so it was a clean double off the bat. With Colton Cowser running from first, the math was pretty easy: If the ball hits the wall, Cowser scores. That’s why the broadcast cut to Cowser rounding second; he was the focus of attention at that point.

In his younger years, Springer might have gotten to that one standing up. But even missing a step or two, he has outstanding defensive instincts. He realized there was little downside and plenty of upside in trying to make a tough play, then pulled it off perfectly:

Every little thing about that is gorgeous. He was into the slide with legs extended by the time the ball hit his glove. He set his feet and lifted his body off the turf without using either hand, which let him complete the transfer from glove to throwing hand more quickly. Check out his left foot as he pivoted into the throw; his toe was pointed in the wrong direction at first, so he gave a quick jab to establish the correct position. Then he ripped the throw, off balance and falling away, hitting the cutoff man on the fly. Cowser had rounded second before Springer even started his slide, and yet the ball was back in an infielder’s hands by the time he stepped on third.

Small potatoes? Sure. He didn’t record an out or even prevent the hitter from getting to second. But keeping a runner from scoring, even with one out, has value. The O’s didn’t score in this inning, and that definitely wouldn’t have been true if Springer hadn’t made the play so seamlessly. And seriously, he was way off the line for that one. Here’s where he started the play:

The Jays like to shade Springer that way against lefties, but it’s nowhere near a straight-up right field position. Look at where he was standing against righties:

Now, did I pick that particular clip to show you that Andrés Giménez can juggle a baseball with his feet? I sure did. But you can see where Springer came into the picture, and he was maybe 20 feet closer to the line than he was against O’Hearn. My point is that it would have been easy for him to play that ball off the wall, or trap it with his momentum going the wrong way, or any number of ways that bad defenders play the ball when it’s not right at them. But Springer still has the elite defensive instincts he showed earlier in his career, and he made the kind of play that he always has. I love it. Even as he ages, you can still see what makes Springer so electric. Oh, and he’s slugging so far this year too. You love to see it.

Programming note: My chat next week will take place Tuesday at 2 p.m. Eastern, as I’ll be out on Monday. Talk to you then, I hope.