Koji Uehara Hangs It Up

On May 20, Koji Uehara announced his retirement from professional baseball. The news was significant for several reasons. First, it was announced during the season. Uehara admitted that he “already decided that I would quit this year, and in my mind I felt three months would be make or break.” He also cited that his fastball just doesn’t have enough to compete in NPB anymore and remarked that him being in the organization would reduce chances for other youngsters. It sounds like, all-around, Uehara has resigned to his fate of being a very old man by baseball standards. It’s sad to hear, but that’s just reality.

Second, it simply feels like an end of an era. The man pitched professionally since 1999. Sure, most major league fans weren’t familiar with him until he signed with the Baltimore Orioles in 2009, but even then, he was 33 years old. Personally, I became familiar with Uehara from his dominance in Japan and his exceptional 2006 World Baseball Classic performance (which is never to be forgotten by Korean baseball junkies like myself).

To understand Uehara’s career, it’s essential to look at his time in Japan. His interest in going to the big leagues goes all the way back to his amateur days. As an ace of the Osaka University of Health and Sports Sciences, Uehara was courted by the then-Anaheim Angels. It was said that the Angels prepared an amount of 300 million yen (just below $3 million in current currency rate) for the righty. Uehara was intrigued by it, but the Yomiuri Giants, who had coveted him for a long time, managed to convince him to stay in Japan, selecting him in the 1998 NPB Draft. Among the notable names selected in the event were other future big leaguers Kosuke Fukudome, Kyuji Fujikawa, and Daisuke Matsuzaka.

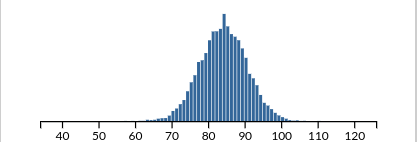

In 1999, his first professional season, Uehara set NPB ablaze with ridiculous numbers. As a 23-year old fresh out of college, the righty went 20-4 with a 2.09 ERA and 179 strikeouts versus 24 walks in 197.2 innings. He also threw a whopping 12 complete games (!) in 25 starts. He had the most wins and strikeouts and the best winning percentage and ERA, making him the quadruple-crown winner among all pitchers. He, of course, won the 1999 NPB Rookie of the Year, a Golden Glove, Sawamura Award (the NPB’s equivalent of the Cy Young Award), was named to the Best Nine, etc. Basically, Uehara had an entrance of the ages. Here’s a peek at his dominance from that season:

As a starting pitcher, he didn’t reach the same kind of brilliance he showed as a rookie, but he was still great. In 2002 for instance, he won another Sawamura Award by going 17-5 with a 2.60 ERA and 182 strikeouts versus 23 walks in 204 innings. He also garnered some stateside attention in fall 2002. In the first game of the MLB-NPB exhibition series, Uehara struck out reigning NL MVP Barry Bonds thrice. His pitching prowess also impressed former AL MVP Jason Giambi. “He had a great forkball,” he said. “He threw it hard enough that you couldn’t sit on it, and he made quality pitches all night.” Read the rest of this entry »