Paul Goldschmidt Is on Fire, and Underrated

If you’ve watched any baseball highlights recently, you’ve probably seen a familiar face lashing line drives. Paul Goldschmidt has a 22-game hitting streak and 28 extra-base hits on the year, which makes him a regular in game recaps. That frequent loud contact has produced one of those hitting lines that makes it clear that we’re still early in the season: .352/.422/.626 screams “small sample!” as loudly as Dan Szymborski does every April.

Sure, that’s true. I don’t think that Goldschmidt is going to post a .402 BABIP on the season. I don’t think that he’s going to keep hitting homers on 18% of his fly balls while also hitting fly balls more frequently than he ever has, or posting a pristine strikeout rate while chasing more often than league average. But again, he’s hitting .352/.422/.626. He has plenty of space to cool off while still being red hot, so let’s look at how he’s setting himself up to succeed.

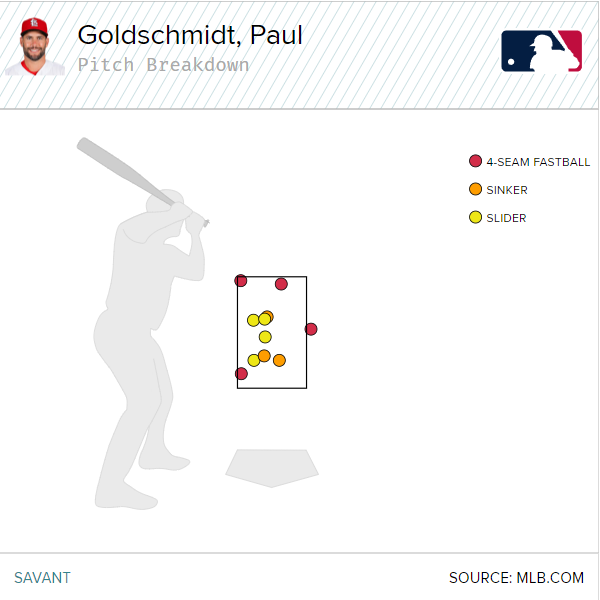

Want to hit a home run? Step one is to swing at a good pitch. Goldschmidt has done exactly that this year; the location and type of the pitches he’s hit for home runs look like a hitting textbook:

Hanging sliders, sinkers that don’t sink, and four-seamers all over the place? That’s how they teach it to you in slugger school.

When he makes contact, he’s pulling the ball more than ever. Eight of his 11 home runs have been pulled, with another two going to straightaway center. The lone exception? It was on that four-seam fastball away that you can see up above. Goldschmidt is, after all, still an excellent hitter, with enough power to hit the ball where it’s pitched. He’s simply picking inside and middle pitches and pulling them into the stands. Read the rest of this entry »