Not All Steep Swings Are Created Equal

There is no baseball topic that gets me more excited than swing diversity. A player’s swing is like a fingerprint: No two are the same. But even similar swings can yield extremely different results. There are many ways to compare swings, but because Vertical Bat Angle (VBA), the angle of the bat at contact relative to the ground, is the most accessible (thanks, SwingGraphs), it’s been my go-to proxy for the last year or so. Of course, you can always use your eyes to visually analyze swings, but having the data to confirm it helps inform the evaluation.

Lately, my video evaluations have focused on hitters with steep VBAs, and even among this group there is a ton of swing diversity. Some take golf-like swings to get to their steep planes and others employ one of my favorite styles: the chicken-wing swing.

Intuitively, it makes sense that hitters with steeps paths are more prone to whiffs than those who have flatter swings. Even so, some of the game’s best contact hitters have swings as steep as some of those who are the most whiff prone. Luis Arraez, for example, has a swing that is just as steep as J.D. Martinez’s, at least according to VBA. Without the data to confirm, it’s hard to know if the same holds true for Attack Angle (AA), the angle of the bat’s path at impact.

To show you exactly what I mean, I’ll compare pairs of hitters with nearly identical average VBAs, but different offensive profiles. A few weeks ago, Davy Andrews wrote about Edouard Julien and the bizarre nature of his platoon splits (and a tune to go along with it). His entire offensive profile drastically changes depending on if he’s facing a lefty or righty. It’s fascinating. After I read the piece, I was immediately curious as to how those trends might relate to Julien’s swing path. At 40 degrees, Julien has one of the steepest VBAs in the majors. It’s almost a perfect diagonal. Here are a few slow motion swings that showcase that:

No matter how high or low the pitch is, Julien manages to get his bat on a diagonal, which last year helped him run an xwOBACON of .443, well above average. His diagonal angle also allows him to crush fastballs. He had a .408 wOBA against heaters but struggled mightily (.287 wOBA) vs. breaking balls. Production against different pitch types is where you tend to see some deviation between hitters with similar VBAs. Like Julien, Freddie Freeman is also a lefty batter with a steep VBA (41.7 degrees), yet despite their similar angles, Julien ran a 44.3% whiff rate against breaking pitches, while Freeman’s whiff rate vs. breaking balls was 27.7%. There are swing components other than VBA that contribute to how such divergence can happen. But before getting to that, let’s check out some of Freeman’s swings from 2023:

Man, Freeman is smooth. Because both he and Julien set up with high hands, they can create a steep path at different pitch heights. This setup allows them to drop their barrel easily and rely on changing posture to adjust to locations. How they do it, though, is where their swings differ. Julien uses more aggressive movements to get to different pitch heights, while Freeman shifts his shoulder plane and avoids more drastic body adjustments. His chicken-wing style is a bit more handsy and less reliant on changing his eye level, and as a result, he has excellent plate coverage. His contact rates on pitches at the top, bottom, and outer thirds of the zone outpace Julien by about eight percentage points in each location.

Two other factors, which are not publicly available, also likely contribute to Freeman’s superior plate coverage: Horizontal Bat Angle (HBA), the horizontal angle of the bat at impact, and bat speed. Freeman, who we’ve already established has a steep VBA on average, appears to be better at altering his swing speeds when necessary, which lets him manipulate his bat angle to cover pitches throughout the zone. You can see this in the third video above, on the changeup breaking down and away from him.

Freeman’s approach also helps him produce against lefties (career 120 wRC+), which is something he has improved upon as he has gotten older (139 wRC+ over the last three seasons). Meanwhile, Julien’s daddy-hack approach sometimes limits his ability to alter his swing speeds and angles, which can often lead to poorly timed swings or mishits and explains why he is prone to hitting groundballs (50.2% last year) despite his steep swing. These issues are more apparent when he faces lefties (22 wRC+, 80% groundball rate), though as Davy pointed out in his Julien piece, he has made only 48 plate appearances against lefties in the big leagues — an incredibly small sample size.

That brings us to the next hitter, Tim Anderson. Even with his steep 39.5-degree VBA, Anderson had a groundball rate above 60% last year. A batter’s contact point has to be extremely deep to pull that off. Here are some swings from him to illustrate that:

Most hitters would struggle to put the ball in play after letting it travel this deep, but TA’s steep barrel and feel for contact in the zone allowed him to pound the ball into the ground over and over and over again last season. The sweeping breaking ball from Rich Hill is the exact type of pitch Anderson would have elevated in years past. Typically, having a steep bat path against an opposite-handed breaking ball is a perfect recipe for an ideal launch angle distribution, but if you’re making deep contact, this is all you can get out of the swing.

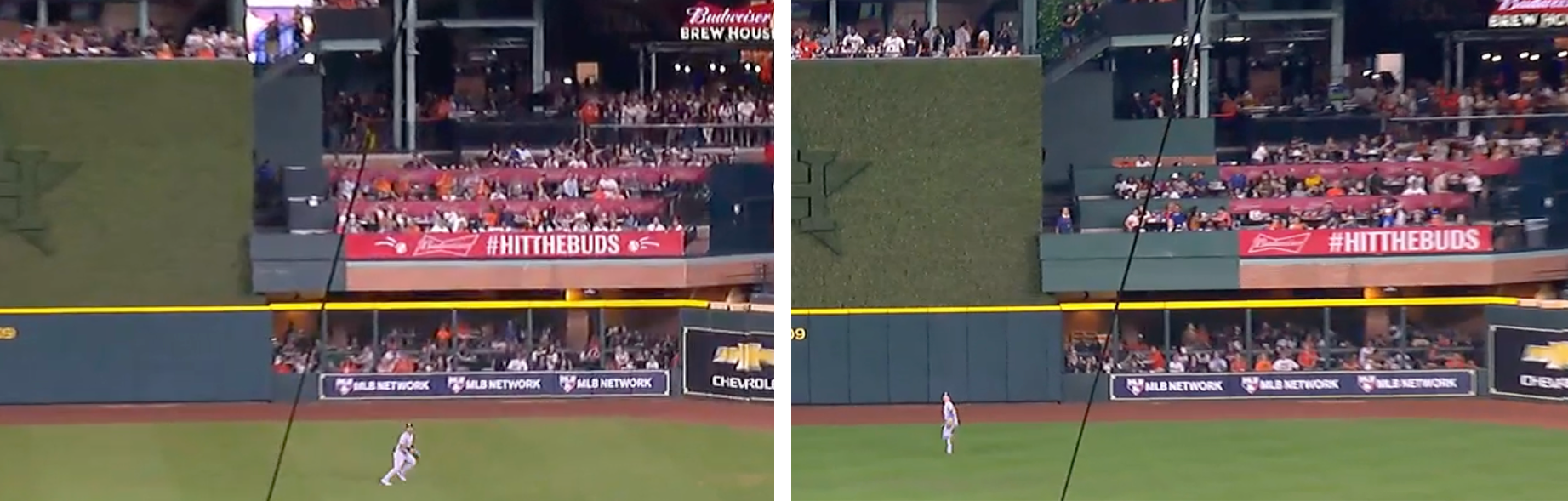

Chas McCormick was the anti-Anderson last season, when he mostly refused to hit the ball on the ground against opposite-handed pitching. He can do this because of how he marries his steep, 38.2-degree VBA with ideal contact points. In 2023, he had a 25.6 GB% against left-handed pitchers. That was the third lowest in baseball behind Jorge Soler and Mookie Betts. Unsurprisingly, by wRC+, they were three of the six most productive right-handed hitters against lefties last year. Here are a few swings from McCormick vs. lefties that show his ability to elevate no matter the zone or pitch:

Even on the well-executed curveball from MacKenzie Gore, McCormick’s barrel was on an upward slope at contact because he connected with the pitch out in front of the zone. This is the type of pitch that Anderson would have pounded into the ground despite the similar steepness at contact, because he would’ve let the pitch get deeper before swinging.

McCormick’s closed stride puts him in a great position to elevate any pitch in the middle of the plate, even if it makes it more difficult for him to square up inside pitches in the top half of the zone. That said, as you can see in the video of his swing against Cole Ragans, he can still get to up-and-in pitches when he holds his posture. The main takeaway is that no matter the zone, his barrel is working on an upward slope through contact, which allows him to do more damage.

Although their swings are similarly steep, these four hitters have different swing types that generate different results. VBA is a great tool to use, but it only tells one part of the story.