Nick Kingham, Mark Prior, and Adam Wainwright on Crafting Their Curveballs

Pitchers learn and develop different pitches, and they do so at varying stages of their lives. It might be a curveball in high school, a cutter in college, or a changeup in A-ball. Sometimes the addition or refinement is a natural progression — graduating from Pitching 101 to advanced course work — and often it’s a matter of necessity. In order to get hitters out as the quality of competition improves, a pitcher needs to optimize his repertoire.

In this installment of the series, we’ll hear from three pitchers — Nick Kingham, Mark Prior, and Adam Wainwright — on how they learned and developed their curveballs.

———

Nick Kingham, Toronto Blue Jays

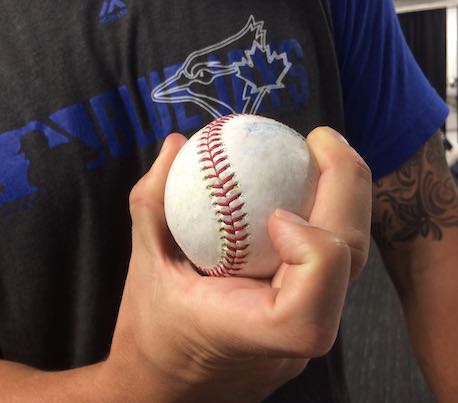

“I’ve been throwing a curveball since ninth grade, or maybe around 13 years old. I guess my dad originally taught it to me. But I never really had a good one. I threw a one-finger curveball for a little while. It was like a suitcase, you know? It kind of just spun and slowed down, and gravity would take it. Then someone told me to try spiking my finger. I’ve been throwing it that way ever since, probably for the last 15 years.

“It’s a standard spike. This is the horseshoe, the tracks go this way, and it’s right on there. Spike it up. There’s nothing… actually, I dig my nail into it. I set my index finger there and make sure that it has enough pressure. That’s comfortable to me. I like to have a secure grip on the ball. Read the rest of this entry »