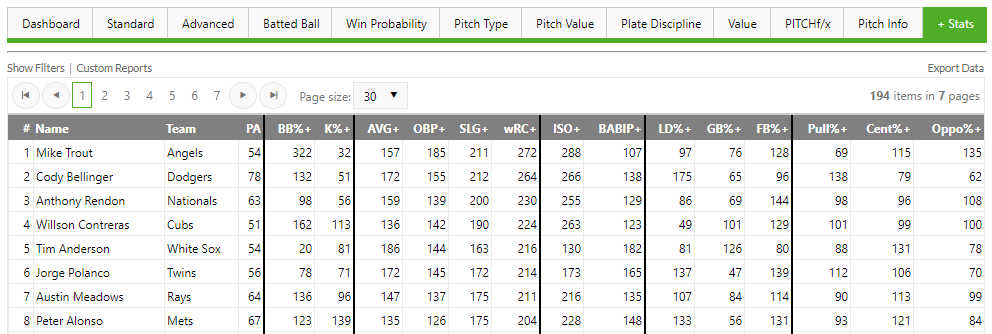

You may have noticed that a number of baseball players have signed extensions this spring. By my count, since Aaron Hicks re-upped with the Yankees on February 25th, 22 players have signed contracts that guarantee them a combined $1.82 billion in new money, and have collectively given 68 years of free agency to the only teams with which they could negotiate. Here are some numbers:

The Spring 2019 Extension Class

A few notes on this table: I’m only interested in new money for the purposes of this article, so Trout’s deal is recorded as starting in 2021, leaving his 2019 and 2020 salaries entirely alone; he would have gotten those anyway. I’ve also excluded any team and vesting options in the “New Guarantee” column because, well, they’re not guaranteed (I have included any buyout in the contract value columns, because that money is guaranteed). I’ve also included players’ age and service time at the beginning of the 2019 season, as well as the earnings they had received or were guaranteed prior to signing extensions, because I think all three factors are relevant to understanding why these particular players might have been open to extensions.

The table is sortable, so you can play around with it as you would like, but I’ll admit that I find it difficult to draw any general conclusions by examining each deal in its particulars. It does seem to be true, broadly speaking, that the deals involving several free agent seasons have been signed mostly by established players (Trout, Arenado, Hicks, Bogaerts, and Goldschmidt) while those deals locking in cost certainty for years already under team control are mostly the province of younger, less-experienced players (Bote, Jiménez, Acuña, Albies, etc.). The young stars who already got paid during the draft, meanwhile (think Kris Bryant and Carlos Correa) are largely absent (Bregman excepted). They, for the most part, don’t need what’s being sold right now.

It is possible to look at each individual extension signed in the past six weeks and find nothing there of great concern — to find, in fact, a number of personal circumstances that militate in favor of one deal or another, from the perspective of a particular player and his idiosyncratic preferences. It is only when the deals are viewed in the collective, when we choose to view owners and players as classes attempting to exercise power upon each other, that the degree to which the modern labor environment has narrowed choices for players becomes visible.

Free agency — the crowning and bitterly contested victory of the first generation of MLBPA members and leaders — is now perceived by many of those who won it as an exercise in humiliation. “Craig Kimbrel is one of the best closers in the history of the game,” one player grumbled to me last week, “and he still doesn’t have a deal [in the middle of April]. It’s ridiculous. Why would I want to put myself and my family through that when the time comes?” Manny Machado and Bryce Harper got paid this offseason, yes, but only after most of the league’s franchises had convincingly demonstrated that they were unwilling to compete for the two men’s services. Players got the message loud and clear.

One interpretation of this set of facts might be to suggest that our present position — in which powers collectively won are only being effectively exercised by highly specific tranches of the player population — is the consequence of the market “sorting itself out,” literally assigning to different groups of players different prerogatives and different rewards that result from one choice or another. But baseball is not a free market. Baseball is a group of 30 owners in constant, though only occasionally explicit, contention with the union labor that is its raison d’etre. That means that insights from economics, with its neat lines of preference and consequence, can tell us only so much about the state of the game today. We must turn as well to political science, which is the study of power and how it’s used.

A labor environment that is the product of power relations between two parties naturally in contest with one another does not have a state of equilibrium from which we have somehow fallen and to which we can soon return with one technical adjustment or another. It only has two camps competing with one another over a given pool of resources, and being more or less effective in their exercise of power over the other in order to enable that competition. That makes it a normative, and not exclusively a positive (read: objective) exercise.

Baseball’s owners have of late been remarkably effective in their exercise of power over the players with whom they are in contest, to the point that it is possible to point to a hundred individual deals made in those years and find few wanting in isolation and yet a union full of players who are convinced, and not without reason, that they are in the process of being hosed. Individual choices made among an array of options limited by an exercise of power against those individuals as a group are not particularly meaningful choices at all. The last year has brought with it an awakening of player consciousness to the narrowing of choices they face, a realization that something must be done, and an increasing willingness to do it. The question, of course, is what.

Here, I think, there is room for optimism. There is no particular reason that players and owners should have to tear each other down in public quite so often as they have, even as they will always remain inevitably in conflict. There are ways that the two camps can collaborate to grow the game such that it generates more money for everyone, as we saw clearly after the agreement reached after 1994 strike set the table for an unprecedented period of revenue growth for baseball. Ads like “Let The Kids Play” are important because they build power for players and the league alike, and grow reserves of good will that can later be turned into money, which can thereafter be used to expand the circle of players receiving the lion’s share of dividends from the game’s windfalls, to players in their first six years of big-league time, perhaps, or even to those in the minor leagues. Whether or not the players are actually being hung out to dry right now, many of them think they are, and that perception may well lead to a period of labor unrest that shrinks the scope of the game’s cultural meaning in a way that we haven’t seen since ’94.

I hope that doesn’t happen. And in the meantime, I hope that fans will continue to grow in their understanding that deals which look good, or at least reasonable, in isolation can begin to smell poorly in combination, and that just because a given deal is understandable does not make it justifiable, or something we should necessarily be happy about. In other, simpler, words: Can does not necessarily mean should. Thinking about the recent deals as a result of a competition of power, rather than the inevitable result of some market-clearing activity, opens the door to expressions of opinion on the balance of the power that results.

We as fans of the game have the means, through our voices and our wallets, to express our opinions on the balance of power in major league baseball, and I can think of no particular reason we should want to shore up the position of owners as a class having considered that balance. Major league baseball — as opposed to baseball as an amateur game we play only for ourselves, or our friends — exists because of the cultural meaning we fans assign to it, and the money and attention we pay to effectuate that meaning. That makes us shared stakeholders in its future, perhaps not as entitled to a voice in its direction as the players who play it and the league that facilitates it, but entitled enough to an opinion nonetheless. What we say matters, and how we choose to react to the choices teams have made this offseason can and should affect the way the game moves forward.