After a whirlwind 24-hour period in which the National Basketball Association, the National Hockey League, and Major League Soccer all announced suspensions of their regular season games in the wake of local restrictions on the size of mass gatherings as a means of slowing the spread of the novel coronavirus, Major League Baseball has followed suit. Following a conference call involving commissioner Rob Manfred and the 30 team owners, the league has shut down its spring training schedules in both Arizona and Florida and will delay the start of the regular season, which was scheduled to begin on March 26, by at least two weeks.

Here’s the statement from MLB:

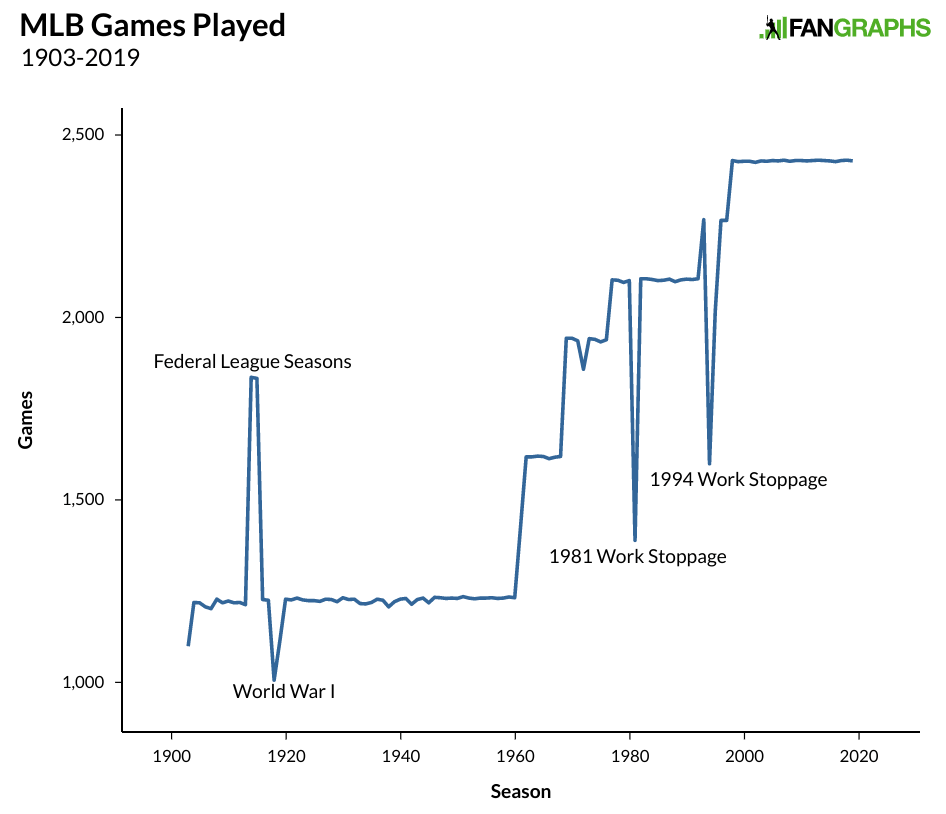

This is the first time since 1995 that the start of the season has been delayed; that year, following the resolution of the strike that wiped out the 1994 World Series, the schedule was shortened to 144 games. MLB’s two-week assessment should be taken with a grain of salt given the fluidity of the situation; just two days ago, the aforementioned leagues banded together to issue a joint statement regarding the closure of locker rooms and clubhouses to the media, a comparatively minor deviation from business as usual. The situation escalated rapidly on Wednesday, as the World Health Organization officially declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic and a top U.S. health official (Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) recommended against the assembly of large crowds for sporting events. It took around two hours between the revelation that an NBA player (Utah Jazz center Rudy Gobert) had tested positive and the league’s decision to suspend play due to the need to quarantine players or advise those who had been exposed to Gobert to self-quarantine. The NBA reportedly told teams on Thursday that its suspension would last for a minimum of 30 days.

Via the New York Post’s Joel Sherman, the expectation is that MLB teams will ask players to remain at spring sites, where they have access to team medical personnel and can continue to work out; however, players can go as they please. Dodgers manager Dave Roberts told reporters that players will be allowed to continue training at their Camelback Ranch facility but that the pace of workouts would be dialed back, and players could go home if they choose. The Brewers are hosting optional workouts for players on Friday and Monday but not over the weekend, and there will be no media availability until Monday. Meanwhile, the Yankees’ current plan is to remain in Tampa, and potentially play intra-squad or simulated games, though that may also change.

Schedule-wise, while nothing official has been announced, The Athletic’s Zach Buchanan reported via Twitter, “Diamondbacks CEO Derrick Hall said the idea now is to pick up the season at whatever point on the schedule play resumes. If only a short time has been missed, MLB could add those games on the back end.” Such a situation would be similar to how MLB handled the 2001 season following September 11, when a week’s worth of games was postponed and then made up after the previously scheduled end of the regular season, such that all teams except the Yankees and Red Sox completed 162-game schedules.

Such policies have not been announced officially, however, and a host of other unanswered questions involving salaries for major and minor leaguers (none of whom get paid during spring training, except per diem meal money), and service time, also loom. Per the Associated Press’ Ronald Blum:

If regular-season games are lost this year, MLB could attempt to reduce salaries by citing paragraph 11 of the Uniform Player’s Contract, which covers national emergencies. The announcement Thursday said the decision was made “due to the national emergency created by the coronavirus pandemic.”

“This contract is subject to federal or state legislation, regulations, executive or other official orders or other governmental action, now or hereafter in effect respecting military, naval, air or other governmental service, which may directly or indirectly affect the player, club or the league,” every Uniform Player’s Contract states.

The provision also states the agreement is “subject also to the right of the commissioner to suspend the operation of this contract during any national emergency during which Major League Baseball is not played.”

Ugh. Obviously, this is sad news for the sport we love and the season we’re hotly anticipating, but those concerns are secondary in the face of a public health crisis during which schools and other institutions have been closed and people have become sick or died; the worldwide confirmed case count as of Wednesday is upwards of 127,000 as of Wednesday, and the death toll is approaching 5,000. We can hope that the games return to us in short order, but right now, nobody really knows what’s in store.