Mike Trout’s Inevitable Decline

Time is the ultimate badass. No matter how great you are, no matter how amazing you are at planning, time always wins in the end. And so it is in baseball as in other things. Mike Trout is, in many ways, the reigning king of baseball, that rare player who enters every season as the nearly-undisputed best in the game. Trout is no longer the young phenom and will turn 30 in just under 18 months, the threshold past which your baseball youth is symbolically gone. Young talent debuts every year while Trout inches closer and closer to retirement, and the day will come when he’s no longer baseball’s clear best.

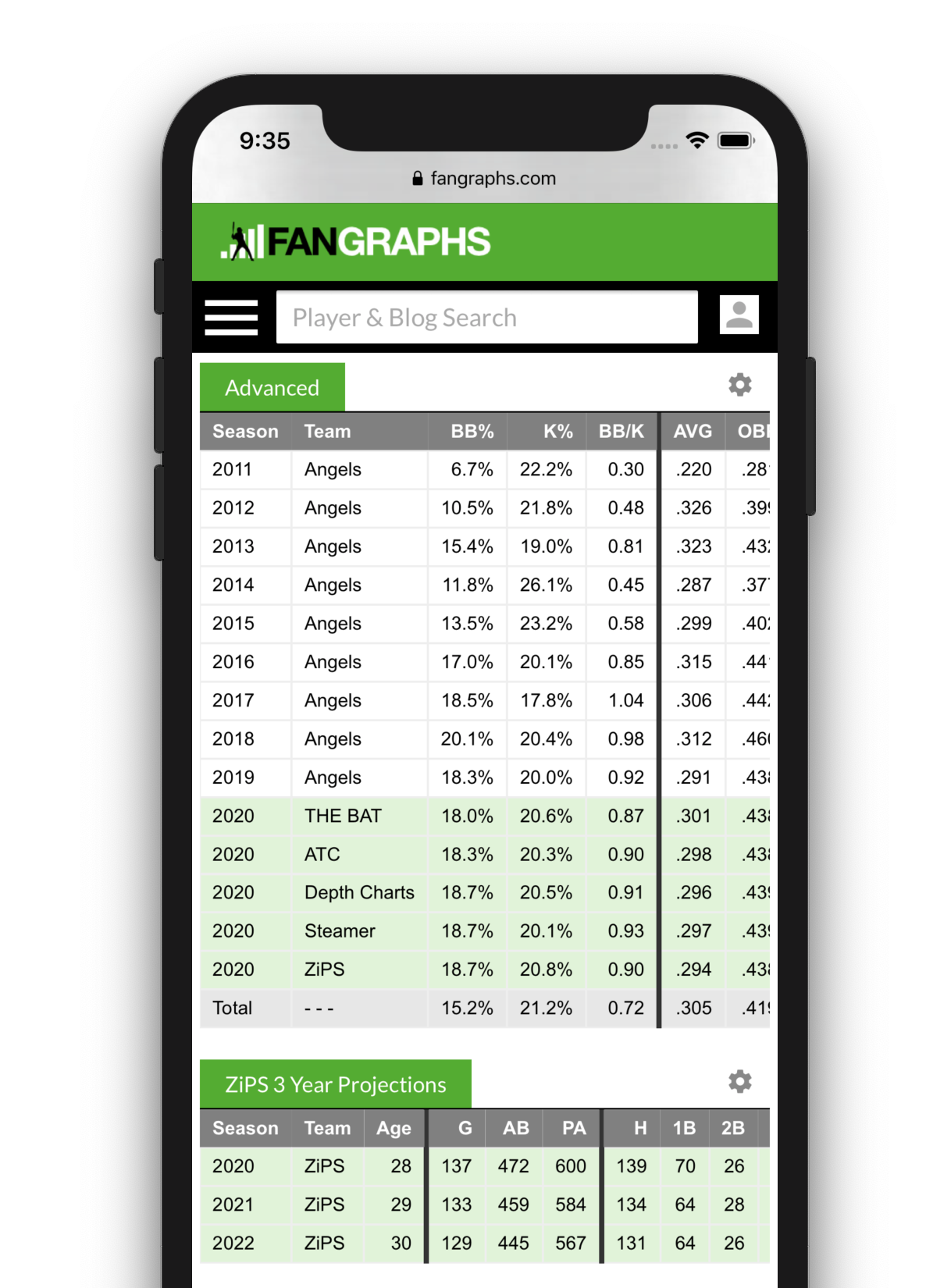

Just being the best player projected coming into the season is practically enough to ensure your baseball immortality. I went back to the start of the modern era (1901) and collected the top WAR projection for every season, instructing ZiPS to calculate a Marcel-like method for the seasons prior to 2003, when the ZiPS projections did not exist. This is a quick way to demonstrate Trout’s dominance compared to other elite players in baseball history:

| Season | Name |

|---|---|

| 1901 | John McGraw |

| 1902 | Cy Young |

| 1903 | Cy Young |

| 1904 | Honus Wagner |

| 1905 | Honus Wagner |

| 1906 | Honus Wagner |

| 1907 | Honus Wagner |

| 1908 | Honus Wagner |

| 1909 | Honus Wagner |

| 1910 | Honus Wagner |

| 1911 | Ty Cobb |

| 1912 | Ty Cobb |

| 1913 | Ty Cobb |

| 1914 | Ty Cobb |

| 1915 | Tris Speaker |

| 1916 | Eddie Collins |

| 1917 | Walter Johnson |

| 1918 | Ty Cobb |

| 1919 | Ty Cobb |

| 1920 | Ty Cobb |

| 1921 | Babe Ruth |

| 1922 | Babe Ruth |

| 1923 | Rogers Hornsby |

| 1924 | Babe Ruth |

| 1925 | Babe Ruth |

| 1926 | Rogers Hornsby |

| 1927 | Babe Ruth |

| 1928 | Babe Ruth |

| 1929 | Babe Ruth |

| 1930 | Rogers Hornsby |

| 1931 | Babe Ruth |

| 1932 | Babe Ruth |

| 1933 | Babe Ruth |

| 1934 | Jimmie Foxx |

| 1935 | Jimmie Foxx |

| 1936 | Lou Gehrig |

| 1937 | Lou Gehrig |

| 1938 | Lou Gehrig |

| 1939 | Mel Ott |

| 1940 | Joe DiMaggio |

| 1941 | Joe DiMaggio |

| 1942 | Joe DiMaggio |

| 1943 | Ted Williams |

| 1944 | Charlie Keller |

| 1945 | Stan Musial |

| 1946 | Snuffy Stirnweiss |

| 1947 | Hal Newhouser |

| 1948 | Hal Newhouser |

| 1949 | Ted Williams |

| 1950 | Ted Williams |

| 1951 | Stan Musial |

| 1952 | Jackie Robinson |

| 1953 | Jackie Robinson |

| 1954 | Stan Musial |

| 1955 | Duke Snider |

| 1956 | Duke Snider |

| 1957 | Mickey Mantle |

| 1958 | Mickey Mantle |

| 1959 | Mickey Mantle |

| 1960 | Ernie Banks |

| 1961 | Willie Mays |

| 1962 | Mickey Mantle |

| 1963 | Willie Mays |

| 1964 | Willie Mays |

| 1965 | Willie Mays |

| 1966 | Willie Mays |

| 1967 | Willie Mays |

| 1968 | Ron Santo |

| 1969 | Carl Yastrzemski |

| 1970 | Carl Yastrzemski |

| 1971 | Bob Gibson |

| 1972 | Fergie Jenkins |

| 1973 | Johnny Bench |

| 1974 | Bert Blyleven |

| 1975 | Joe Morgan |

| 1976 | Joe Morgan |

| 1977 | Joe Morgan |

| 1978 | Mike Schmidt |

| 1979 | Mike Schmidt |

| 1980 | Mike Schmidt |

| 1981 | George Brett |

| 1982 | Mike Schmidt |

| 1983 | Mike Schmidt |

| 1984 | Mike Schmidt |

| 1985 | Cal Ripken |

| 1986 | Rickey Henderson |

| 1987 | Wade Boggs |

| 1988 | Wade Boggs |

| 1989 | Wade Boggs |

| 1990 | Wade Boggs |

| 1991 | Rickey Henderson |

| 1992 | Barry Bonds |

| 1993 | Barry Bonds |

| 1994 | Barry Bonds |

| 1995 | Barry Bonds |

| 1996 | Barry Bonds |

| 1997 | Barry Bonds |

| 1998 | Barry Bonds |

| 1999 | Barry Bonds |

| 2000 | Pedro Martinez |

| 2001 | Pedro Martinez |

| 2002 | Randy Johnson |

| 2003 | Barry Bonds |

| 2004 | Barry Bonds |

| 2005 | Barry Bonds |

| 2006 | Alex Rodriguez |

| 2007 | Albert Pujols |

| 2008 | Albert Pujols |

| 2009 | Albert Pujols |

| 2010 | Albert Pujols |

| 2011 | Albert Pujols |

| 2012 | Clayton Kershaw |

| 2013 | Mike Trout |

| 2014 | Mike Trout |

| 2015 | Mike Trout |

| 2016 | Mike Trout |

| 2017 | Mike Trout |

| 2018 | Mike Trout |

| 2019 | Mike Trout |

| 2020 | Mike Trout |

There are a couple of oddities in there, mostly caused by the difficulty of projecting a player who missed seasons due to war service, but otherwise it’s a Who’s Who of the Hall’s inner circle. I’d wager that in 50 years, all but two of these players will be in the Hall of Fame, with Charlie Keller likely on the outside, and Snuffy Stirnweiss certainly so. (If I’m still around in 50 years to test this prediction, I also wager I’ll be a very shouty, curmudgeonly 91-year-old.)

In terms of the number of years at the top of the heap, Trout’s eight seasons already puts him in third place in modern baseball, behind only Babe Ruth and Barry Bonds. In terms of uninterrupted reigns, Trout’s eight consecutive seasons ties Bonds’ 1992-1999 stretch, meaning that if he has the top projection entering 2021, he’ll have earned his spot as the giocatore di tutti giocatori in baseball.

| Name | Reigned | Years |

|---|---|---|

| Barry Bonds | 11 | 1992-1999, 2003-2005 |

| Babe Ruth | 10 | 1921-1922, 1924-1925, 1927-1929, 1931-1933 |

| Mike Trout | 8 | 2013-2020 |

| Honus Wagner | 7 | 1904-1910 |

| Ty Cobb | 7 | 1911-1914, 1918-1920 |

| Mike Schmidt | 6 | 1978-1980, 1982-1984 |

| Willie Mays | 6 | 1961, 1963-1967 |

| Albert Pujols | 5 | 2007-2011 |

| Mickey Mantle | 4 | 1957-1959, 1962 |

| Wade Boggs | 4 | 1987-1990 |

| Joe DiMaggio | 3 | 1940-1942 |

| Joe Morgan | 3 | 1975-1977 |

| Lou Gehrig | 3 | 1936-1938 |

| Rogers Hornsby | 3 | 1923, 1926, 1930 |

| Stan Musial | 3 | 1945, 1951, 1954 |

| Ted Williams | 3 | 1943, 1949-1950 |

| Carl Yastrzemski | 2 | 1969-1970 |

| Cy Young | 2 | 1902-1903 |

| Duke Snider | 2 | 1955-1956 |

| Hal Newhouser | 2 | 1947-1948 |

| Jackie Robinson | 2 | 1952-1953 |

| Jimmie Foxx | 2 | 1934-1935 |

| Pedro Martinez | 2 | 2000-2001 |

| Rickey Henderson | 2 | 1986, 1991 |