Back in March, my colleague Dan Szymborski wrote a piece about how playoff projections changed based on the length of the season. At the time, all we knew was that the season had been suspended, and that whatever season we eventually got was likely to be shorter than the one we expected at the start of the calendar year. How many games we’d ultimately lose was a mystery — Dan ran projections for 140 games, 110 games and, most pessimistically, 81 games. After observing the results, he reached the reasonable conclusion that the shorter the season is, the more margin there is for worse teams (on paper, at least) to sneak into the playoffs, and for supposedly elite teams to fall short.

Three months later, it turns out even 81 games was too ambitious of a dream. After much back-and-forth with the players, owners have officially decided to enact a season of just 60 games, beginning on July 23 or 24 and concluding in the final week of September, when a typical regular season would have also finished. With that number officially in place, our playoff odds have been updated to reflect the dramatic shortening of the season, and the result is a similarly dramatic re-imagining of teams’ fortunes:

FanGraphs Playoff Odds, 162-game season vs. 60-game

| Team |

162-game Playoff% |

60-game Playoff% |

162-game WS% |

60-game WS% |

| Yankees |

88.8% |

75.2% |

14.4% |

11.6% |

| Rays |

69.0% |

59.7% |

6.7% |

6.3% |

| Red Sox |

34.5% |

39.1% |

1.9% |

2.6% |

| Blue Jays |

1.8% |

7.9% |

0.0% |

0.2% |

| Orioles |

0.0% |

0.1% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Twins |

68.3% |

62.2% |

7.3% |

6.4% |

| Indians |

43.6% |

48.2% |

3.3% |

3.7% |

| White Sox |

29.0% |

37.0% |

1.4% |

2.0% |

| Royals |

0.9% |

5.9% |

0.0% |

0.1% |

| Tigers |

0.1% |

2.2% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Astros |

91.6% |

78.7% |

18.1% |

15.2% |

| Athletics |

48.1% |

43.2% |

3.4% |

3.4% |

| Angels |

18.3% |

27.7% |

0.8% |

1.4% |

| Rangers |

0.9% |

11.7% |

0.2% |

0.4% |

| Mariners |

0.1% |

0.9% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Nationals |

66.7% |

53.3% |

5.0% |

4.8% |

| Braves |

58.2% |

52.7% |

4.0% |

4.8% |

| Mets |

42.6% |

40.7% |

2.3% |

2.9% |

| Phillies |

18.1% |

23.6% |

0.5% |

1.0% |

| Marlins |

0.4% |

3.2% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Cubs |

53.0% |

48.4% |

3.2% |

3.4% |

| Reds |

35.0% |

39.5% |

1.7% |

2.4% |

| Brewers |

33.8% |

37.9% |

1.5% |

2.1% |

| Cardinals |

29.5% |

34.8% |

1.1% |

1.8% |

| Pirates |

0.8% |

5.2% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Dodgers |

97.6% |

86.3% |

21.0% |

20.3% |

| Padres |

40.7% |

36.4% |

1.6% |

2.1% |

| Diamondbacks |

17.1% |

23.1% |

0.4% |

0.8% |

| Rockies |

5.8% |

10.9% |

0.0% |

0.3% |

| Giants |

0.7% |

4.2% |

0.0% |

0.1% |

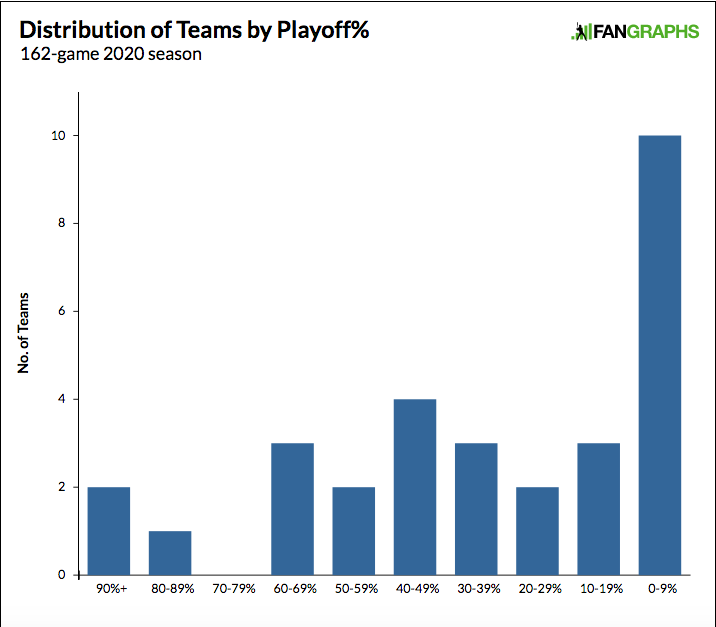

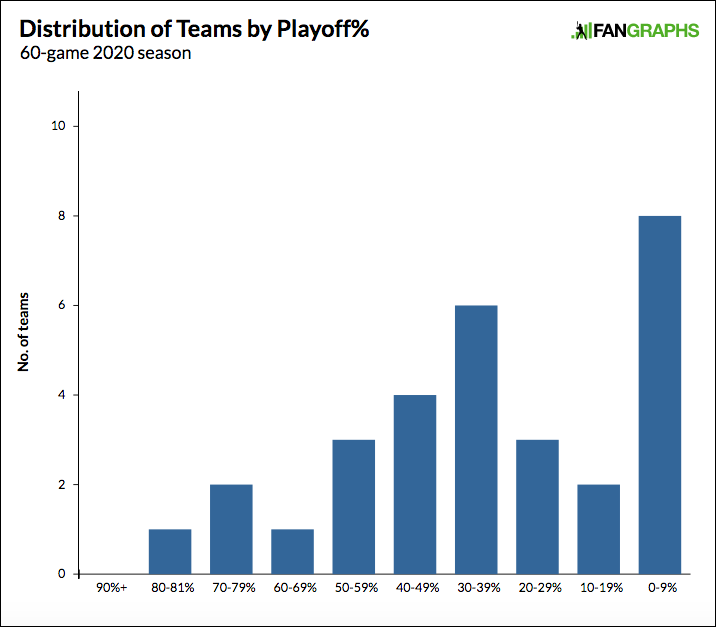

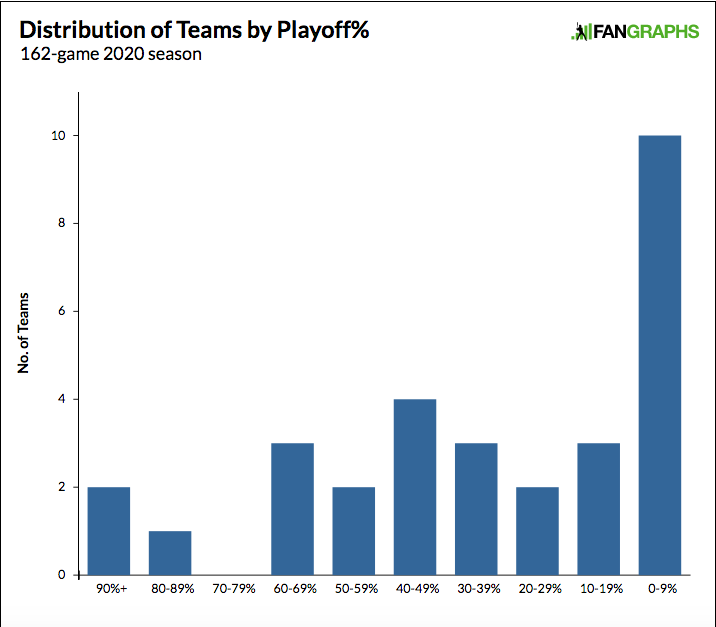

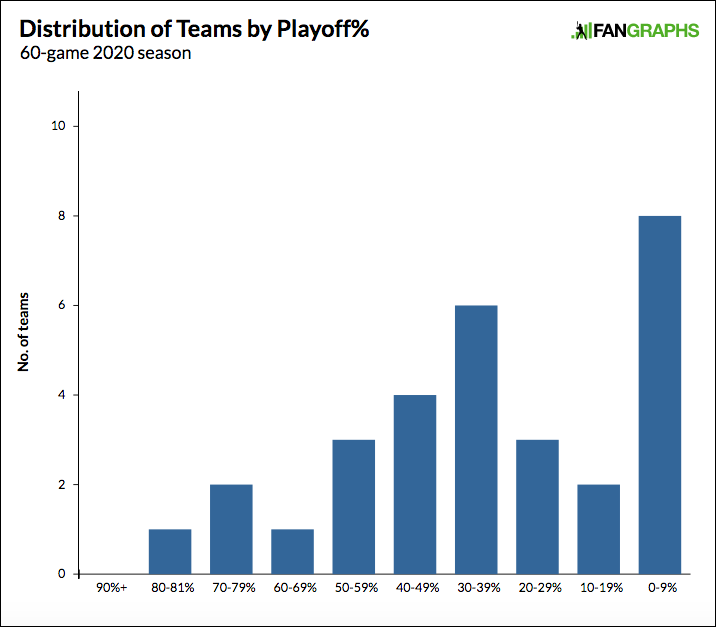

This table is helpful because it includes all of the information that forms the base of what we’re discussing here — the changes in each team’s playoff and title odds with a shortened season — but to be honest, looking at each team individually like this doesn’t really drive home the kind of shift that has occurred. On its own, the Rangers moving from a 1-in-100 chance at the postseason to a 1-in-10 chance or the Yankees falling from a nearly 9-in-10 chance to a 3-in-4 chance is interesting, but doesn’t really fundamentally change our thinking. The Rangers are probably out, and the Yankees are probably in. Instead, let’s group teams together by their playoff odds, and see how that distribution plays out under the two season lengths:

This better conveys the heart of the changes — from both the front and back of the spectrum, teams have been pulled into the middle. In a 162-game season, 20 teams had playoff odds of either above 60% or below 20%. In a 60-game season, just 14 teams have such a distinction, meaning that a plurality of teams now fall somewhere between a 1-in-5 and 3-in-5 shot.

While the Rays and Nationals have been pulled in from the front of the pack, we see many more teams creeping up from what used to be the bottom tier of actual playoff hopefuls. The Angels make a huge jump relative to their peers, moving from 18.3% playoff odds to 27.7%, while the White Sox (28% to 37%), Diamondbacks (17.1% to 23.1%), and Phillies (18.1% to 23.6%) bite similar chunks out of the advantages the teams ahead of them once had.

And if the gap between 20% and 60% playoff odds I mentioned just above still sounds like a big one, it really isn’t in theory. Consider that under our 162-game projections, the Braves were given a 58.2% shot at the playoffs and an expected win total of 86 games. The Angels, meanwhile, had just an 18.3% chance at the playoffs, with an expected win total of 83 games. That’s three measly games separating two teams with a 40% gap in their playoff odds. Now, to be clear, more goes into playoff odds than just win total. The Braves play in a division without a clear-cut favorite, and in a league where just one team was projected to win 90 games, while the Angels’ division does have a clear-cut favorite, and play in a league that includes four teams expected to win 90 games. Context plays a big role here, but the slim difference in their win totals does show you just how little could separate a team with 1-in-5 playoff odds from a team with 3-in-5 odds.

That’s in a 162-game season. Cut that total down to 60, and the projected win distribution invites even more chaos:

Look at that tall bar on the left. That includes the Washington Nationals, who are projected to win their division and finish with the second-best record in the NL, and the San Diego Padres, who have less than a 15% chance to win their division and are projected to have the eighth-best record in the NL. Fewer than two wins, on average, separate them now. That’s how you go from two teams being 26 points apart in playoff odds to them being just 17 points apart.

This extreme parity is most apparent in the NL Central, where the top four teams are virtually indistinguishable from one another:

NL Central Projections, 162 games

| Team |

Proj W |

Proj L |

Division% |

WC% |

Playoff% |

WS% |

| Cubs |

85 |

77 |

38.1% |

14.8% |

53.0% |

3.2% |

| Brewers |

82 |

80 |

21.6% |

12.2% |

33.8% |

1.5% |

| Reds |

82 |

80 |

22.0% |

13.0% |

35.0% |

1.7% |

| Cardinals |

81 |

81 |

17.8% |

11.7% |

29.5% |

1.1% |

| Pirates |

69 |

93 |

0.4% |

0.4% |

0.8% |

0.0% |

NL Central Projections, 60 games

| Team |

Proj W |

Proj L |

Division% |

WC% |

Playoff% |

WS% |

| Cubs |

32 |

28 |

31.4% |

17.0% |

48.4% |

3.4% |

| Brewers |

31 |

29 |

23.7% |

15.8% |

39.5% |

2.4% |

| Reds |

31 |

29 |

22.4% |

15.5% |

37.9% |

2.1% |

| Cardinals |

31 |

29 |

20.0% |

14.7% |

34.8% |

1.8% |

| Pirates |

26 |

34 |

2.5% |

2.5% |

5.2% |

0.0% |

There was already so little separating the middle three teams, and now the Cubs have nearly been absorbed into that group as well. Whoever wins this division is probably going to be a decent enough club, but they’re also going to inevitably be the beneficiaries of a season determined a lot by luck. And the Central isn’t the only division like that. Let’s check back in with the Nationals, Braves, and the rest of the NL East:

NL East Projections, 162 games

| Team |

Proj W |

Proj L |

Division% |

WC% |

Playoff% |

WS% |

| Nationals |

88 |

74 |

41.4% |

25.3% |

66.7% |

5.0% |

| Braves |

86 |

76 |

33.0% |

25.2% |

58.2% |

4.0% |

| Mets |

84 |

78 |

19.6% |

23.0% |

42.6% |

2.3% |

| Phillies |

79 |

83 |

6.0% |

12.1% |

18.1% |

0.5% |

| Marlins |

67 |

95 |

0.0% |

0.3% |

0.4% |

0.0% |

NL East Projections, 60 games

| Team |

Proj W |

Proj L |

Division% |

WC% |

Playoff% |

WS% |

| Nationals |

33 |

27 |

32.8% |

20.5% |

53.3% |

4.8% |

| Braves |

33 |

27 |

32.3% |

20.5% |

52.7% |

4.8% |

| Mets |

31 |

29 |

22.2% |

18.5% |

40.7% |

2.9% |

| Phillies |

30 |

30 |

11.4% |

12.1% |

23.6% |

1.0% |

| Marlins |

25 |

35 |

1.3% |

1.9% |

3.2% |

0.0% |

Out of every team in baseball, the Nationals are arguably the most-harmed by the shortening of the season. Their 13.4-point drop in playoff chances is second behind the Yankees for the biggest in the sport, with the Astros and Dodgers close behind, but unlike those other three teams, they aren’t able to escape with a still-comfortable lead over the rest of their division. Their once sizable advantage over Atlanta has essentially evaporated, despite the fact that the Braves’ chances at both the division and the Wild Card took a hit as well.

This is what happens when you try to predict what’s going to happen in a situation where every game will mean more, but their sum total will tell you less. Depending on what kind of fan you are or what team you cheer for, that could either terrify or thrill you. And while this might make you angsty at the idea of an “undeserving” team making the playoffs or even winning the World Series, it’s worth remembering that even full seasons don’t always do a great job of awarding the title to team we think is best. Just for this year, it’s probably for the best if we don’t worry much about who actually makes the playoffs. Let’s just hope we get a postseason at all.