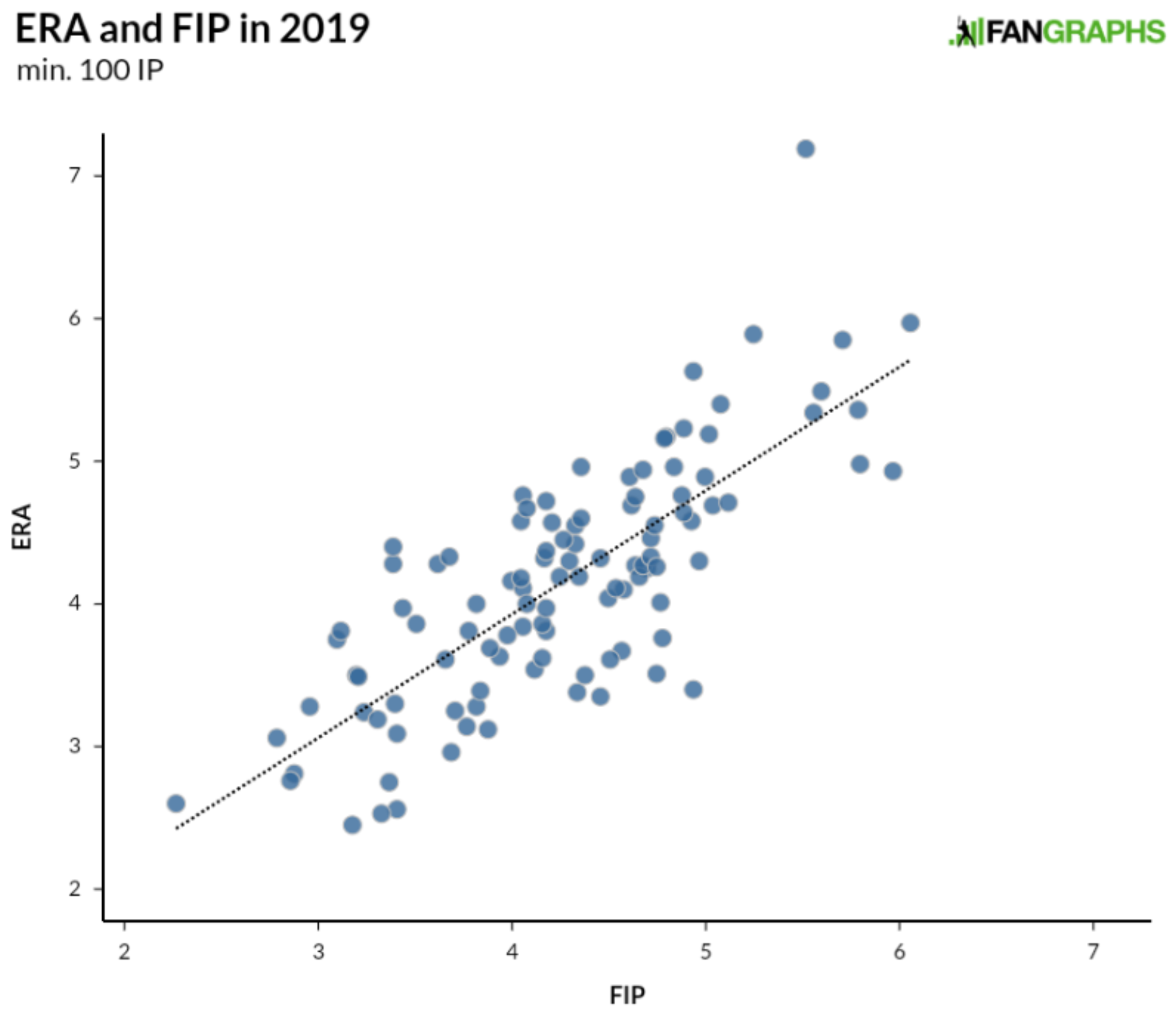

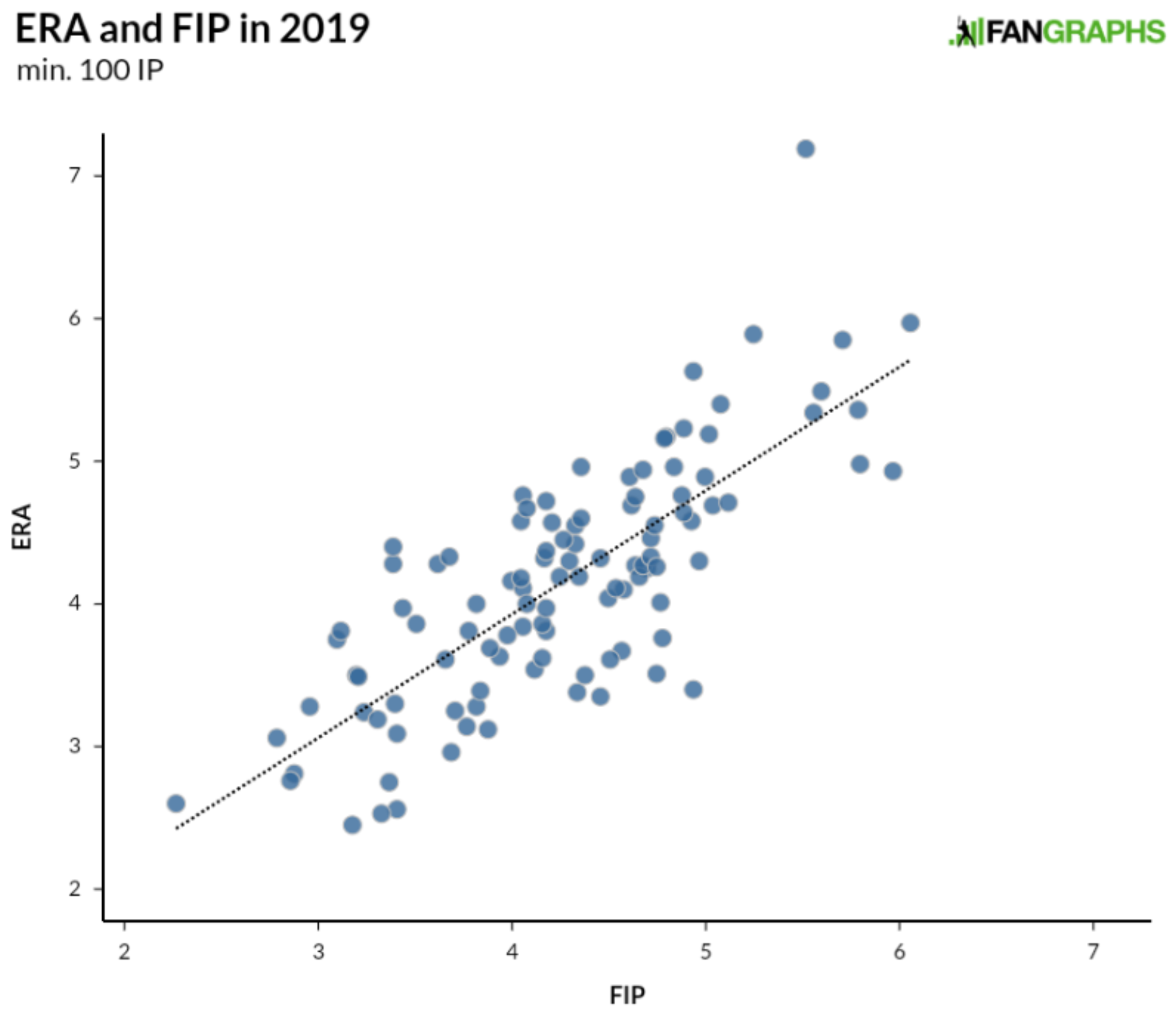

For the most part, a pitcher’s FIP is going to line up pretty well with his ERA over the course of a season or a career. There are 240 starting pitchers with at least 1,000 innings over the last 25 years and all but seven of them have a FIP within half a run of their ERA. Even over the course of an individual season, we typically see most pitchers with an ERA and a FIP around the same mark. Over the last 25 seasons covering more than 3,500 individual pitching seasons of at least 100 innings, the r-squared is .61. This season, there are over 100 pitchers with at least 100 innings; the graph below shows their FIPs and ERAs (all stats are through September 5):

With the exception of Antonio Senzatela way up top, we see a pretty distinct pattern moving up and to the right. Within this cluster of players, there isn’t a perfect relationship. A perfect relationship would make one of the stats duplicative and useless. ERA and FIP both measure results on the field, with ERA accounting for the players who cross home plate after getting on base when the pitcher was on the mound (and the trip home wasn’t made possible by an error), while FIP measures strikeouts, walks, and homers. Every year, a good number of pitchers have an ERA higher than their FIP and vice versa. As far as explaining the difference between the two numbers using readily available statistics goes, BABIP and left-on-base percentage explain much of the gap between the two numbers.

With the exception of Antonio Senzatela way up top, we see a pretty distinct pattern moving up and to the right. Within this cluster of players, there isn’t a perfect relationship. A perfect relationship would make one of the stats duplicative and useless. ERA and FIP both measure results on the field, with ERA accounting for the players who cross home plate after getting on base when the pitcher was on the mound (and the trip home wasn’t made possible by an error), while FIP measures strikeouts, walks, and homers. Every year, a good number of pitchers have an ERA higher than their FIP and vice versa. As far as explaining the difference between the two numbers using readily available statistics goes, BABIP and left-on-base percentage explain much of the gap between the two numbers.

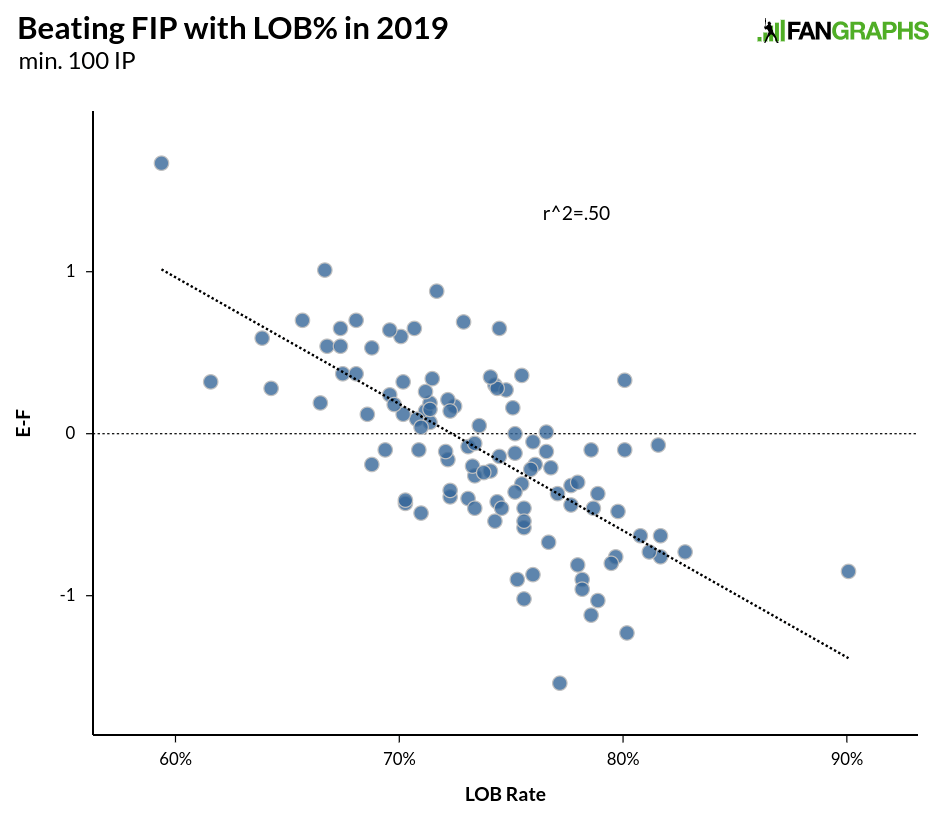

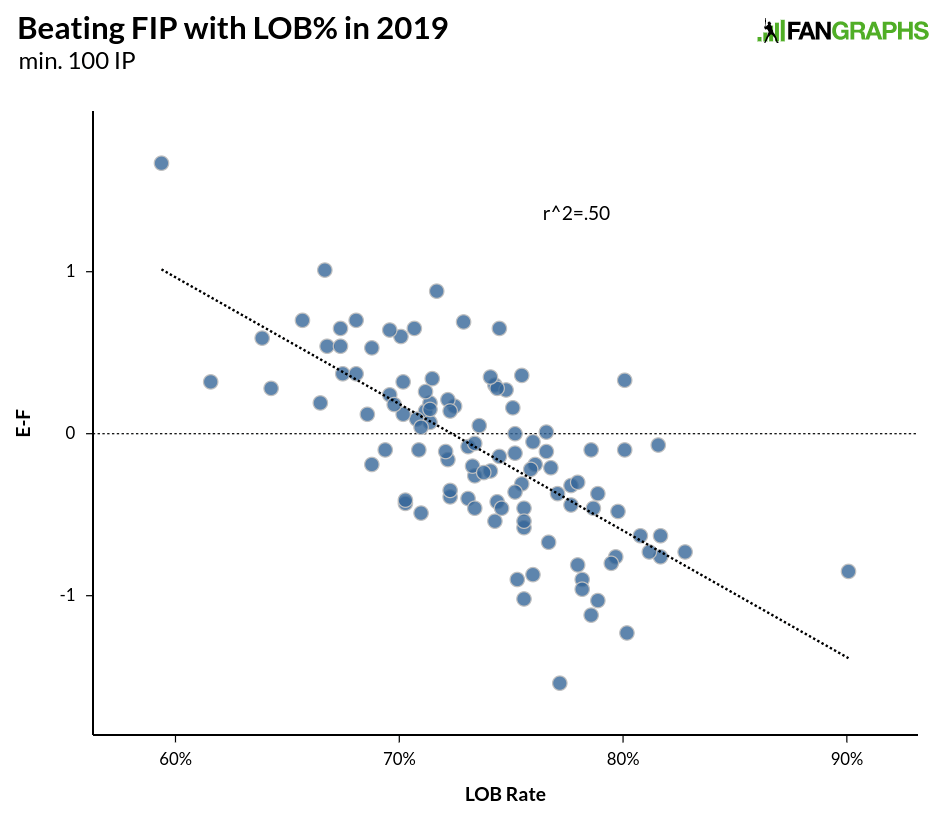

That LOB% would explain some of the gap makes a lot of sense given that stranding more runners than expected is going to keep a pitcher’s runs allowed (ERA) lower than his general performance (FIP). We can see the relationship between ERA-FIP and LOB% for pitchers this season below:

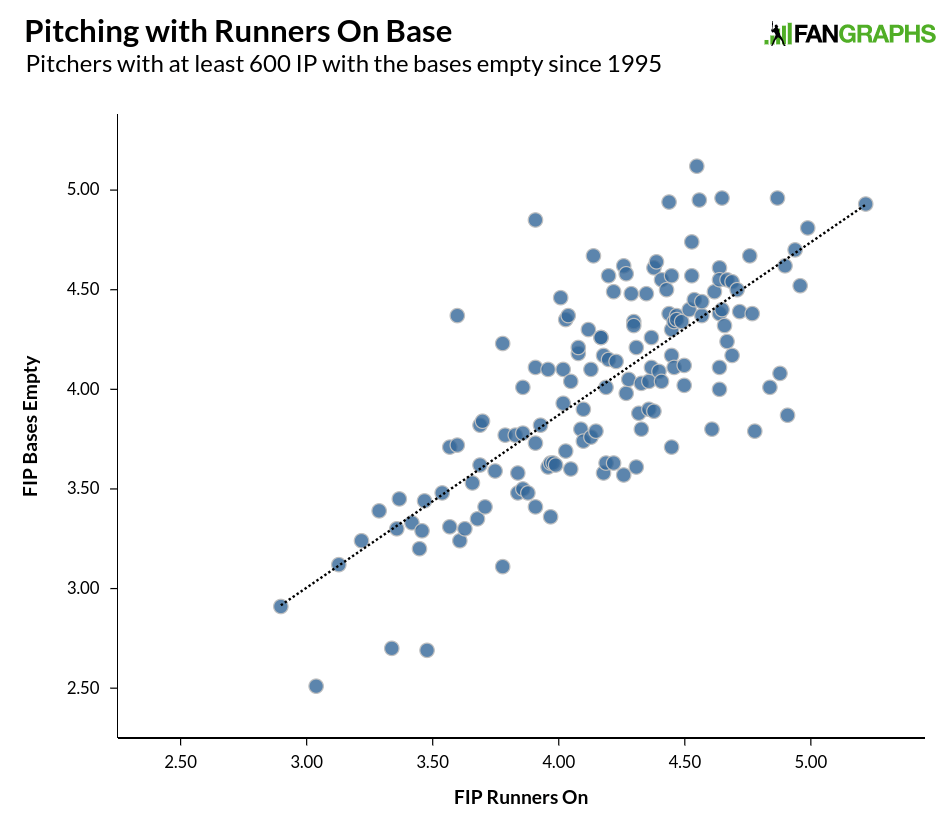

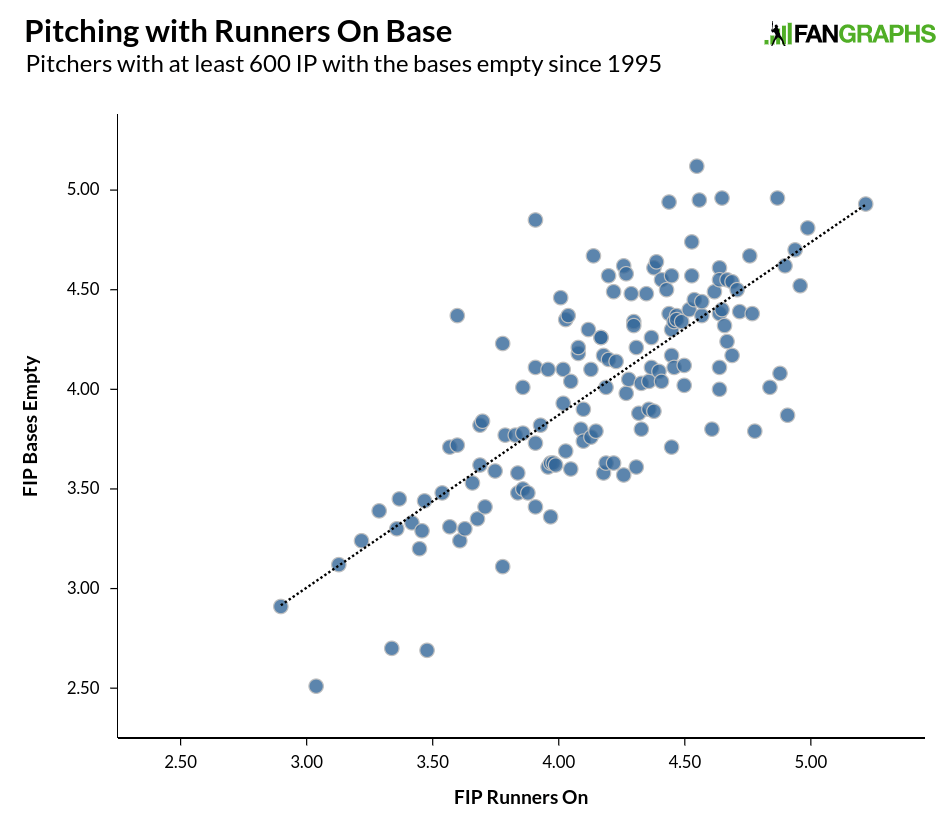

Without delving into whether there’s a skill involved in stranding runners (though better pitchers tend to have higher LOB% due to just being better at getting outs generally), we can see that the more runners stranded and the higher the LOB%, the more likely it is that a pitcher’s ERA is going to be lower than his FIP. The relationship over the past 25 years for individual seasons is stronger than the one above, with an r-squared of .56, but even over just one season, the pattern is apparent. What we are dealing with above is sequencing and what happens when runners are on base compared to overall performance. Generally speaking, pitcher’s perform similarly with runners on base and with the bases empty, with a slight increase in FIP for everyone with runners on base:

This isn’t to say that some pitchers aren’t worse pitching from the stretch, or that some pitchers don’t change their strategy to more effectively get batters out with runners on base. But generally speaking, pitchers perform a little bit worse with runners on base, though in a fairly uniform pattern as seen in the graph above. Unless you are Doug Davis, Scott Kazmir, Jeff Suppan, or Iván Nova, then with runners on base, you were within half a run with runners on base or worse.

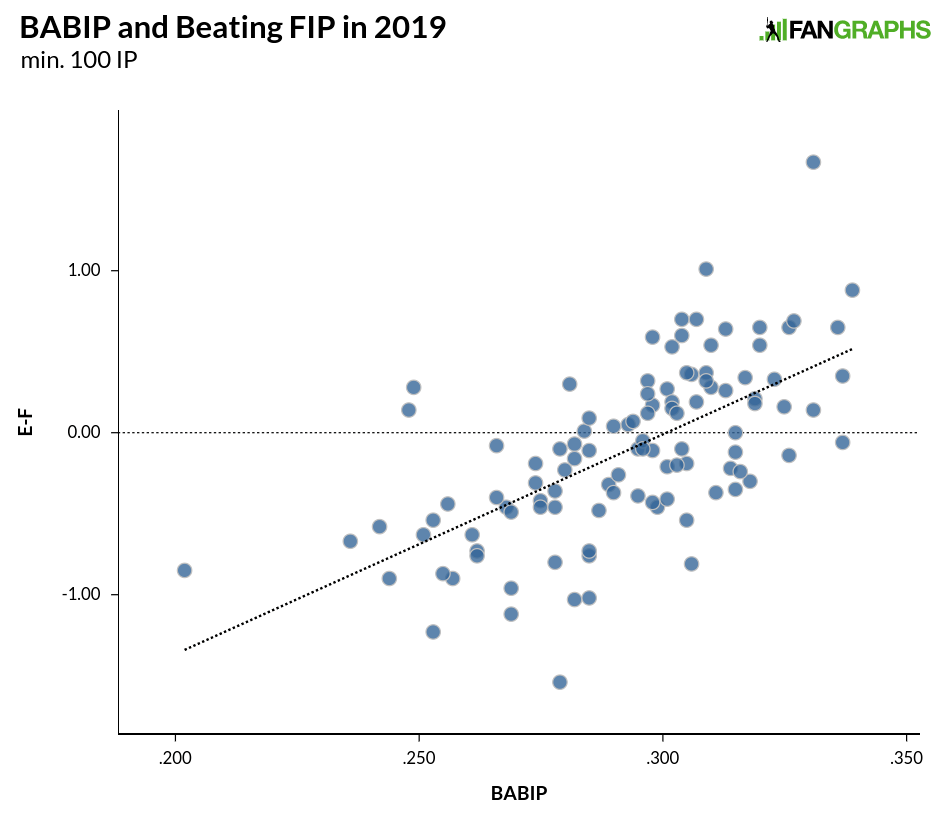

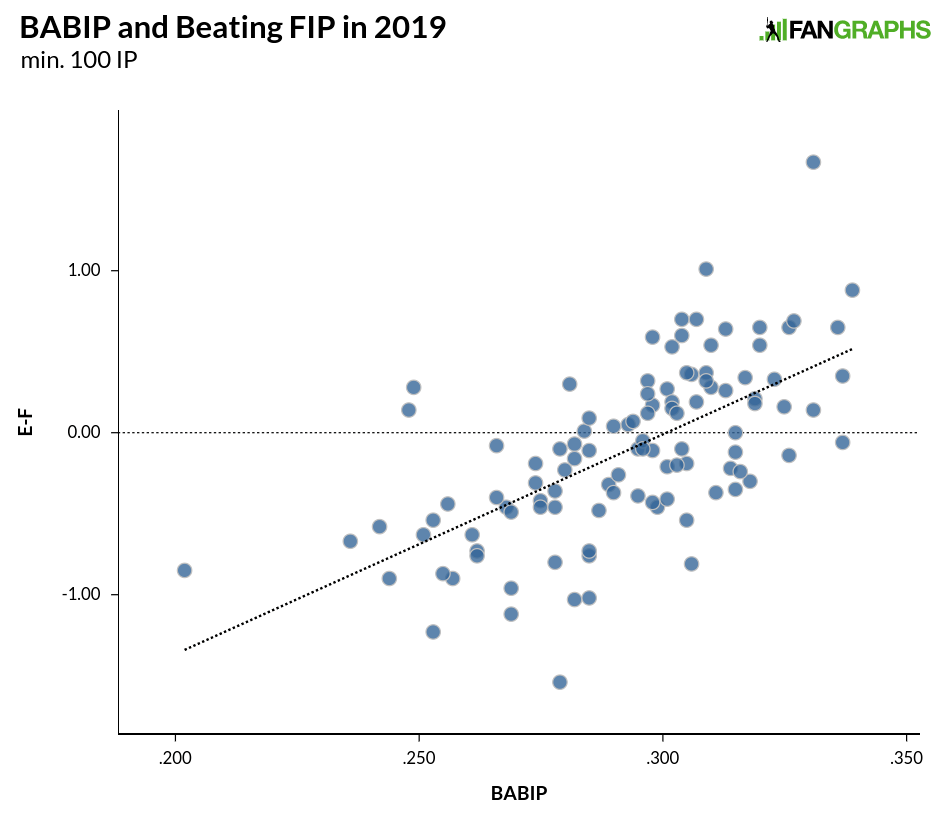

We’ll get back to LOB% in a minute, but first, we should address BABIP. Here’s the relationship between BABIP and the difference between ERA and FIP:

The relationship isn’t as strong as LOB%, but with an r-squared of .41 this season, we can still see a pattern. Over 25 years of individual seasons, the r-squared is .52, nearly the same as LOB% over the same time. While we know that pitchers exert some control over the quality of their contact, over 90% of pitchers with at least 1,000 innings since 1995 are between .270 and .310, and 65% of pitchers are between .285 and .305 (around 10 hits per year at the edges), so even at the extremes we are talking about maybe three or four extra hits per month. That’s not nothing, but over long stretches of time, we generally see the seasonal outliers get closer to their peers.

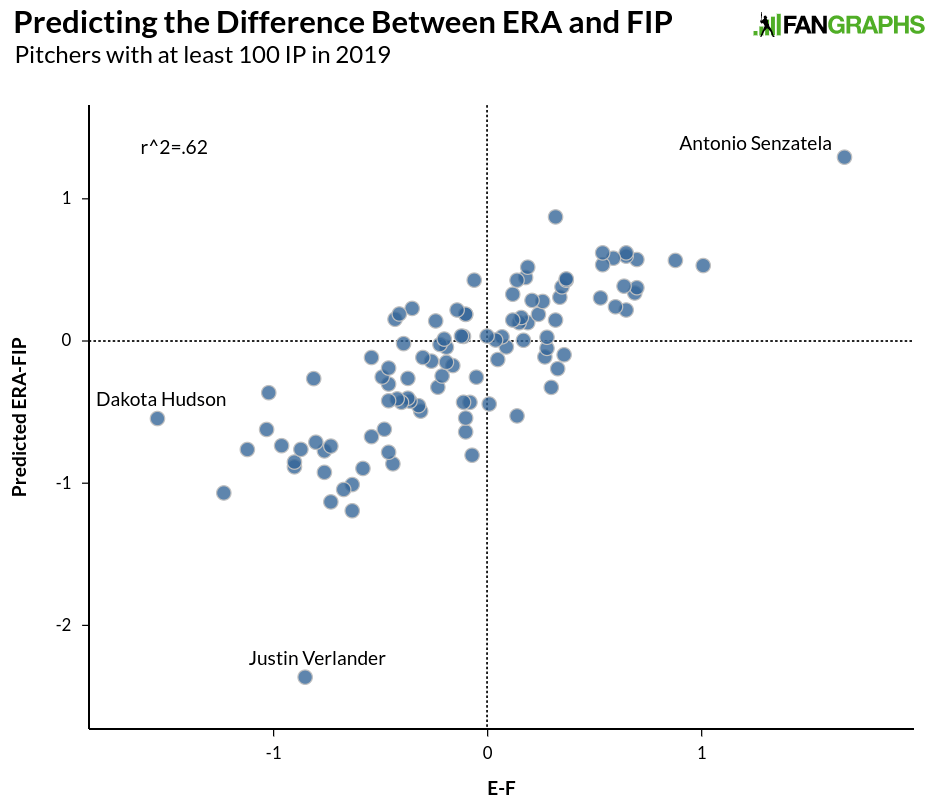

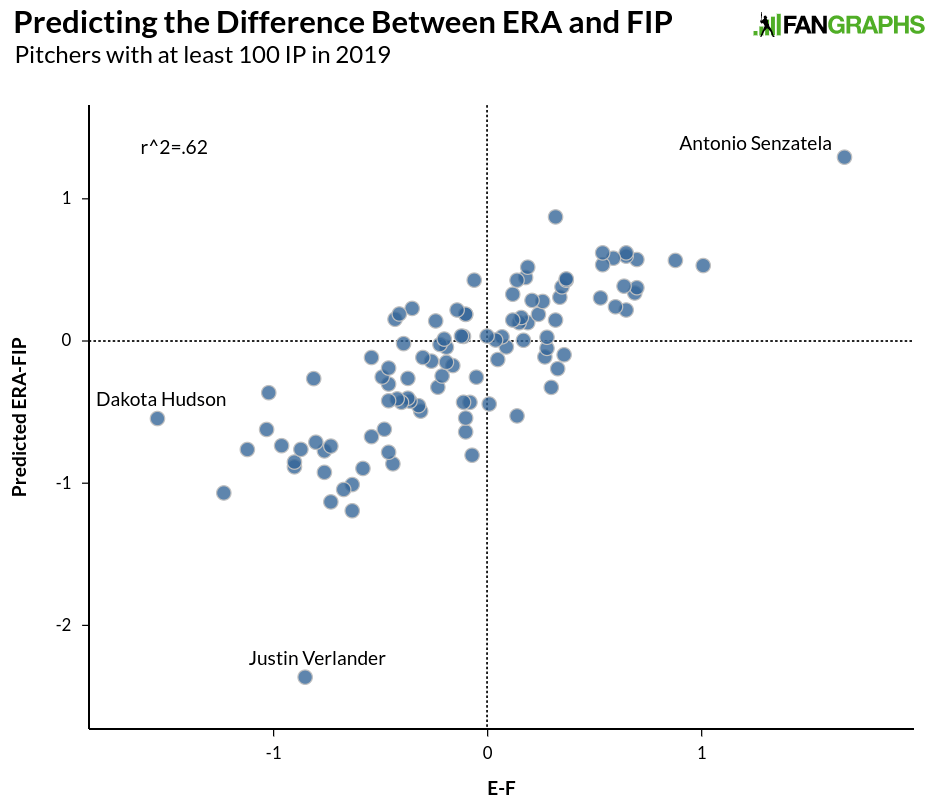

As for just how much BABIP and LOB% capture the difference between ERA and FIP, the answer is they account for the great majority of it. I took all individual seasons from 1995 through last season and ran them through a multiple regression calculator to come up with a formula for predicting the difference between ERA and FIP. The r-squared for the formula for the 3,400 seasons was .75, so BABIP and LOB% are doing a huge amount of the heavy lifting when it comes to explaining the difference between ERA and FIP. I put the same formula into this year’s numbers and this is how they came out:

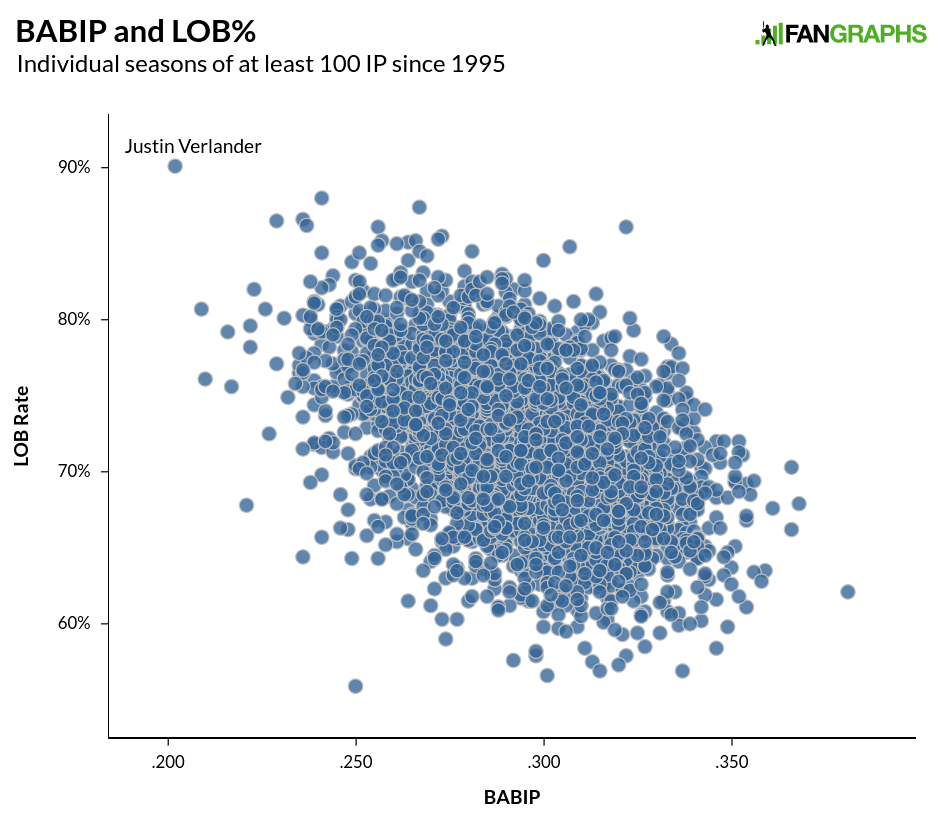

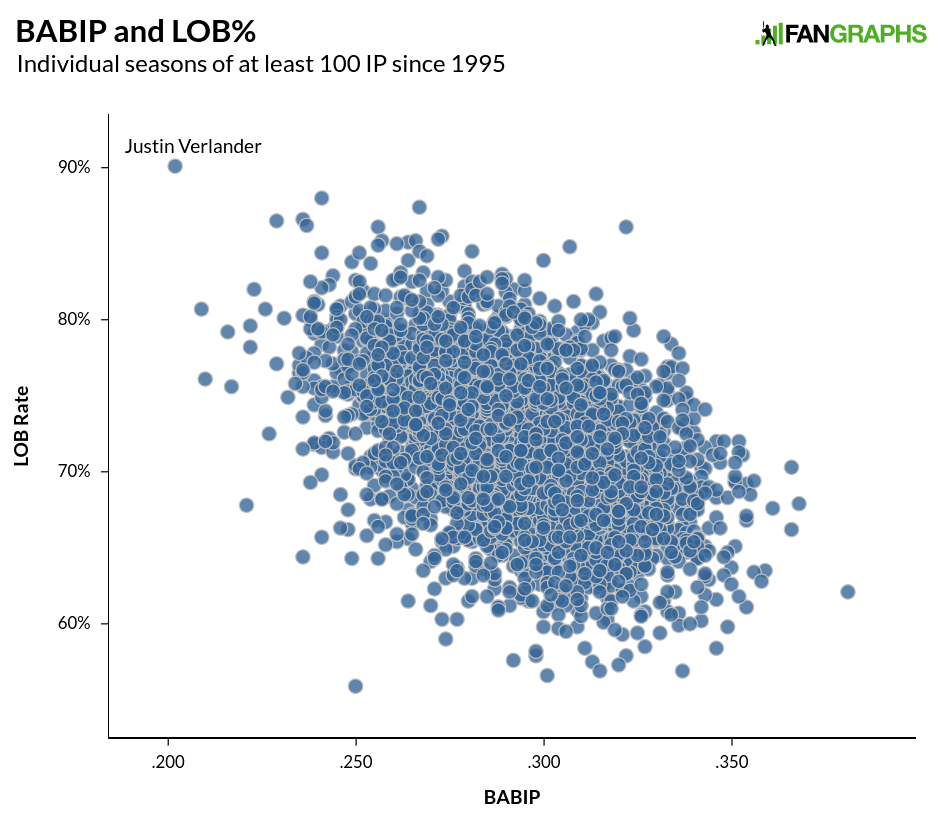

We still see some outliers, but overall, the formula did a very good job predicting the difference between ERA and FIP using LOB% and BABIP. There are a few outliers. Dakota Hudson jumps out, but his larger ERA-FIP discrepancy is pretty easily explained by 15 unearned runs. If he had a more normal five earned runs, the difference would be under a run and he’d be in the big group with everybody else. Justin Verlander, on the other hand, appears to be breaking the formula entirely. To see how, here are 3,500-plus individual pitcher seasons with over 100 innings since 1995, and their LOB% and BABIP:

Quite simply, Verlander is having one of the most unusual seasons we’ve ever seen, with the highest LOB% and lowest BABIP in the last 100 years in the same season. As we can see above, there is some correlation between LOB% and BABIP, with an r-squared of .2, but that’s not as strong as either statistic’s relationship with FIP-ERA, and a pitcher’s BABIP’s relationship with his team’s BABIP is around the same strength, with team BABIP and team UZR having a slightly stronger relationship.

While there is certainly a case to be made that pitchers have control over the quality of contact they yield to some extent — no one would deny the existence of groundball pitchers or fly ball pitchers — BABIP doesn’t even necessarily measure contact quality. It counts every batted ball in the park as either a hit or an out, doesn’t include homers at all, and it varies greatly from year to year. Even xwOBA, which includes homers and dials in on the quality of contact, has difficulty finding a relationship year over year on contact. Looking just at in-season results, wOBA on contact has a difficult time becoming reliable.

It’s only natural to want to find a reason why a pitcher’s ERA and FIP are so different, and for that reason to be related to something the pitcher is or isn’t doing. Unfortunately, that isn’t always likely to be the case. In any single season, there are going to be outliers due to the relatively small sample of plate appearances we are dealing with, and almost all of the difference between ERA and FIP can be explained by BABIP and LOB%. While not all of a pitcher’s BABIP and LOB% are due to a pitcher’s defense, sequencing luck, and just general good fortune, a decent amount is just that. Baseball is a team sport and defenses play a large role in run prevention. While it isn’t always easy to admit, luck plays a role as well.

With the exception of

With the exception of