Clevinger Is on the Padres’ Roster and Will Start Division Series Opener

The Padres and Dodgers submitted their rosters for the Division Series on Tuesday morning, a formality for most postseason series but one that this time around carried considerable intrigue. As was hinted by multiple reports in the 24 hours leading up to the deadline, the team has indeed included Mike Clevinger, who has pitched just one inning since September 13 due to issues with his biceps and elbow and who was left off the Wild Card Series roster, and furthermore, they have tabbed him to start Game 1. Dinelson Lamet, who similarly left his September 25 start with tightness in his biceps and missed the Wild Card Series, was not included.

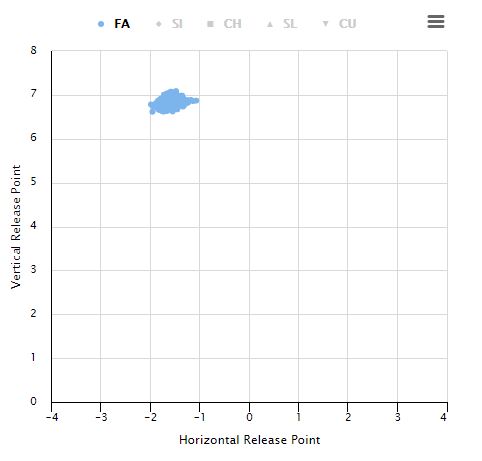

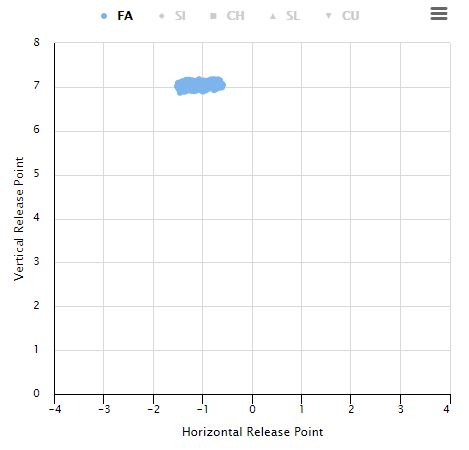

To review: after throwing seven innings of two-hit shutout ball on September 13 against the Giants, Clevinger was scratched from his turn five days later against the Mariners due to soreness in his right biceps. After the team and the 29-year-old righty were reassured by a bullpen session on September 21, he started against the Angels two days later, and pitched a 1-2-3 first inning, striking out both David Fletcher and Mike Trout, but his velocity was down a bit, and he didn’t return for the second inning. The Padres said his biceps was bothering him again, and two days later, they revealed that he had been diagnosed with posterior elbow impingement (a side effect of inflammation) and given a cortisone shot.

Clevinger resumed playing catch on September 28 and then threw a 23-pitch bullpen session the next day, but was left off the Wild Card Series roster. After a higher-intensity bullpen session on Sunday, the Padres sounded notes of optimism that made their way into a handful of tweets suggesting he was likely to be added and to start Game 1. That is indeed the case. Read the rest of this entry »