The last 15 months have not gone particularly well for Greg Holland. Coming off a solid return from Tommy John surgery with the Rockies in 2017 — albeit one with a lesser second half than first — he bypassed a reported multiyear offer to return, then was met with a frosty reception amid a free agent market that was generally more hospitable to relievers than other players. He finally signed a one-year, $14 million deal with the Cardinals after Opening Day, but struggled to the point of being released on August 1. After salvaging his season at least somewhat with a strong showing with the Nationals over the final two months, he hit free agency again. On Monday, the 33-year-old righty reportedly agreed to a one-year, $3.5 million-plus-incentives deal with the Diamondbacks, pending a physical. It’s a living, but ouch.

Admittedly, it’s suboptimal to carry a season with a 4.99 ERA, 3.83 FIP, 0.3 WAR, and just three saves into a market flooded with alternatives coming off stronger showings, but one might have thought that the Scott Boras client could have built upon his late-season resurgence in Washington and the lack of a qualifying offer this time around. Then again, it was presumably Boras’ misread of Holland’s market last winter that got him into this jam in the first place. At least this time, he’s going to spring training.

By not signing until two days after Opening Day last year — and that only after Luke Gregerson was lost to a hamstring injury — Holland missed the entirety of exhibition season, and after making just a pair of tune-up appearances with the Cardinals’ Hi-A Palm Beach affiliate, he walked four out of the five batters he faced in his April 9 debut. He didn’t get his first save chance until April 27, but he blew that, and he never assumed the full-time closer role. He never found his control in St. Louis, and a three-week stint on the disabled list for impingement in his right hip, from late May to mid-June, didn’t help. All told, in 32 appearances totaling 25 innings with the Cardinals, his walk, strikeout, and earned run totals were identical: 22 (7.92 per nine) — not what you want. Six days after being released, he joined the Nationals, and at least righted the ship, posting a 0.84 ERA and 2.97 FIP while striking out 31.3% of hitters in 21.1 innings as the team played out the string.

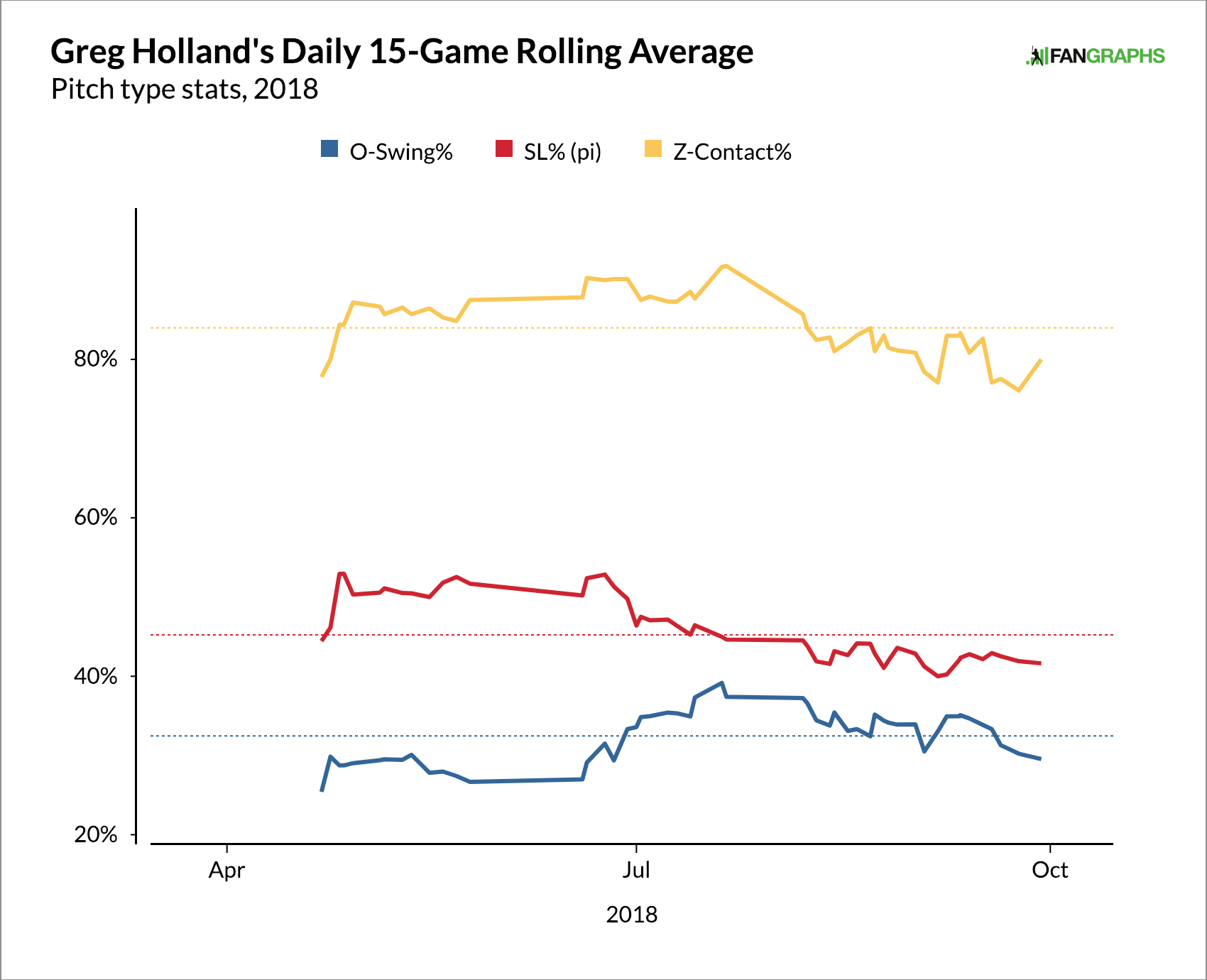

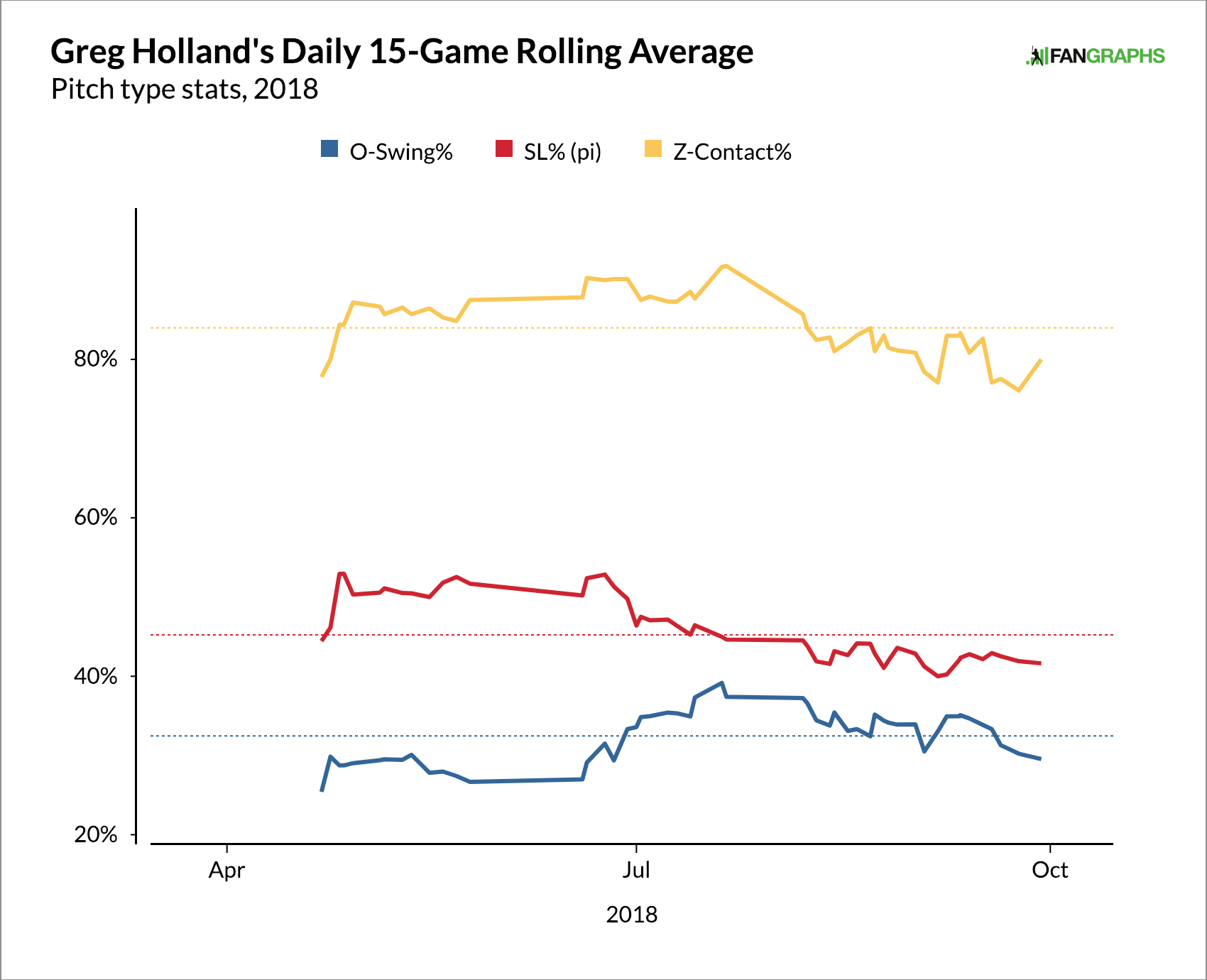

The key, or at least one of them, was a more reliable slider that generated more chases and less zone contact when he backed off using it quite so heavily:

According to Brooks Baseball, while with St. Louis, Holland’s slider was hit for a .268 average and .357 slugging percentage, with a 19.8% whiff rate (37.3% whiffs per swing), while with Washington, the slider yielded an .081 batting average (all singles) with a 25.2% whiff rate (48.5% whiffs per swing). His fastball became less of a meatball with the transition as well (.342 AVG/.463 SLG before, .208/.375 after, with a whiff rate climbing from 4.2% to 10.7%); via Baseball Savant, his xwOBA dropped from .354 with the Cardinals to .239 with the Nationals. Granted, we’re dealing with small samples in terms of innings and pitches, with the latter ranging from 30 plate appearances ending with fastballs in Washington to 60 PA ending with sliders in St. Louis, but whatever changed did seem to work, allowing him to recover his first-half 2017 form — when he earned All-Star honors with the Rockies — if not his magic with the Royals. Life is just different when your fastball averages 92.9 mph instead of 96.9 (his average in 2013, according to Pitch Info).

On that note, it’s worth a brief historical review. Once upon a time, Holland ranked among the game’s elite relievers. From 2011 — his first full season in the majors — to 2014, he posted ERAs below 2.00 three times out of four, with FIPS below 2.00 twice. Over that span, only three pitchers (Craig Kimbrel, Eric O’Flaherty, and Wade Davis) outdid his 1.86 ERA, and only Kimbrel surpassed his 1.92 FIP and 9.1 WAR. In August 2012, he assumed the closer duties for the Royals, and over the next two seasons became a key part of their march to respectability, aided by a dominant bullpen. He made the All-Star team in both 2013 and ’14, ranking second in the AL in saves each year. In 2013, he led all relievers in FIP (1.36) while ranking second in WAR (3.0), while in 2014, after placing within the top handful in ERA, FIP, and WAR, he went 7-for-7 in saves while yielding just one run and four hits in 11 innings while striking out 15 during the Royals’ postseason run.

Holland did not get to pitch during the Royals’ 2015 championship run. His velocity dipped from its typical 95-96 mph average into the low 90s in late August, and he was soon discovered to have suffered a partial tear in his ulnar collateral ligament. He tried to pitch through it — reportedly, he had been experiencing elbow discomfort as far back as August 2014 — but went to the sidelines in mid-September, yielding the closer’s job to Davis, and on October 2 went under the knife. He didn’t re-emerge until signing a one-year, $7 million contract with the Rockies in January 2017, a deal that included a mutual option, more on which momentarily.

Holland burst out of the gate in 2017, converting 23 straight save chances with a 1.09 ERA through June 14. He made the NL All-Star team on the strength of a 1.62 ERA and 2.80 FIP; a dreadful 9.1-inning, 14-run stretch in August blew up his second-half stats (6.38 ERA, 4.99 FIP), but he helped the Rockies snag an NL Wild Card berth, and finished with a league-high 41 saves along with a 3.61 ERA and 3.72 FIP (72 ERA- and 81 FIP-).

When Holland signed with the Rockies, he had a $10 million mutual option for 2018, with a $1 million buyout. By reaching either 50 games pitched or 30 games finished, that option converted into a $15 million player option, about on par with his total take in 2017 ($15.1 million) thanks to his having earned $9.1 million in incentive bonuses thanks to his 61 appearances, 58 games finished, and 2017 NL Comeback Player of the Year award. Holland declined the option and the $17.4 million qualifying offer that followed. Later he reportedly snubbed a three-year, $51 or $52 million deal from the Rockies, though whether that was a firm offer or a “conceptual” one (as Buster Olney phrased it) is up for debate. The Rockies instead signed Davis to a three-year, $52 million deal in late December — thanks, old pal — and a better offer apparently never came Holland’s way.

Hence, the mess in which Holland wound up, though he was hardly alone in misreading the market. The exact details of his new contract are unknown at this writing, but he can earn a maximum of $3.5 million in incentives, some of which probably depend upon his returning to closer duty. With Brad Boxberger departed in free agency (unsigned at this writing, actually), it’s not clear yet whether he or Archie Bradley, who excelled in a setup role, will be manager Torey Lovullo’s top ninth-inning choice. If Holland can stay healthy and maintain his old form, he stands to be quite a bargain for the Snakes regardless of his role, but one can’t help imagining that if he could play out the last year-and-change again, he’d be in a much better position than he is today.

![]() iTunes Feed (Please rate and review us!)

iTunes Feed (Please rate and review us!)![]() Sponsor Us on Patreon

Sponsor Us on Patreon![]() Facebook Group

Facebook Group![]() Effectively Wild Wiki

Effectively Wild Wiki![]() Twitter Account

Twitter Account![]() Get Our Merch!

Get Our Merch!![]() Email Us: podcast@fangraphs.com

Email Us: podcast@fangraphs.com