Oakland’s Pitching Staff Is Cruising

Sean Manaea began his start Wednesday night by allowing a home run on his first pitch of the game, and things only briefly got better. After Shin-Soo Choo’s lead-off blast, Manaea retired nine of the next 11 hitters he faced only to have trouble return again in the fourth. He gave up a single to Todd Frazier and a walk to Robinson Chirinos, followed by run-scoring hits from Nick Solak and Isiah Kiner-Falefa, before finally getting his first out of the inning in the form of a sacrifice fly by Rob Refsnyder. With four runs already in on six hits and a walk through 3.2 innings, Oakland manager Bob Melvin moved to his bullpen early, asking right-hander Burch Smith to get his team back on track.

“If you’re Burch Smith, you would love to be able to hand the ball off to somebody in the eighth inning,” A’s analyst Dallas Braden said on the broadcast as Smith tossed his warm-up pitches. In the moment, it sounded optimistic, maybe even a tad foolhardy. Saying something like that is a nice way to remind Oakland fans watching at home that a bad start does not mean hope is lost, and that their team is very much still in the game. But expecting any reliever to go get 11 outs when the starter could only achieve 10 is a pretty tough ask, especially when it’s a 30-year-old journeyman who owns a career ERA north of 6.00.

In reality, Braden almost got it exactly right. Smith pitched two outs into the seventh inning, retiring all 10 hitters he faced on just 33 pitches before Melvin replaced him with T.J. McFarland. McFarland gave up one hit and got two more outs, then Joakim Soria came into the game and retired the final five Rangers hitters of the night. In that time, the A’s hammered a total of four homers and came back to win the game, 6-4. The bullpen was asked to do the heavy lifting, and it did a near-perfect job at it.

That kind of performance has become the norm for the A’s over the first couple weeks of the 2020 season. Here are the most valuable ‘pens in baseball through Wednesday: Read the rest of this entry »

You Can’t Fit Yu Darvish Into a Pitch-Type Box

Yu Darvish’s calling card has always been his dizzying array of pitches. Hard cutter, slow cutter, curve, knuckle curve, slow curve, shuuto — if you can name it, he can probably throw it in a major league game. That’s not an obviously great skill, in the same way as Gerrit Cole’s overpowering fastball or Jacob deGrom’s ability to throw sliders in the mid 90’s with command, but the results speak for themselves: Darvish has the third-highest career strikeout rate of any starter, active or otherwise, and impressive run prevention numbers to boot: his career ERA- and FIP- both check in at a sterling 82.

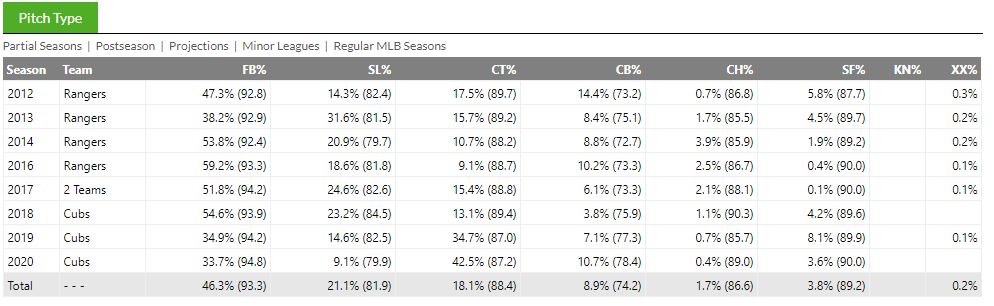

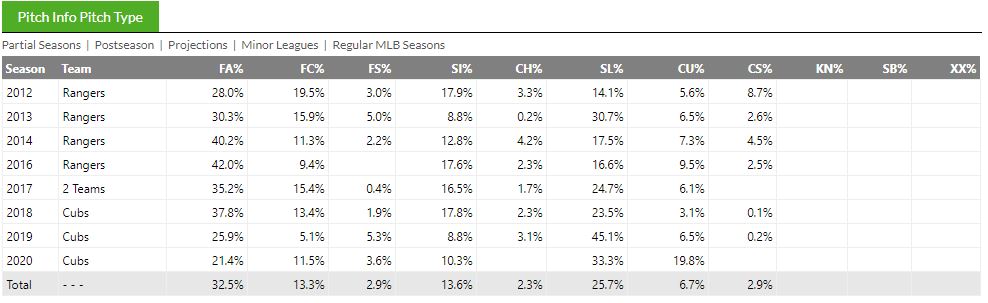

So okay, fine, Yu Darvish has two calling cards: tons of pitches and the ability to use those pitches effectively. Let’s talk about the tons of pitches today, though, because they’re way more fun. Consider, if you will, the two systems we use to classify pitches. Darvish’s career looks like a bingo board on both, but they’re two very different bingo boards. First, our standard pitch types:

It’s a little bit of everything, with a heavy emphasis on cutters in the last two years. Meanwhile, the sliders have gotten slow — a near-career-low 79.9 mph, nearly as slow as his curveball, which has gotten fast. It’s a confusing mess. Next, take a look at pitch types per Pitch Info:

Rafts of sliders! More curveballs! The only thing the two systems seem to agree on is the 3.6% splitters, thrown at a dizzying 90 mph. You can’t see Pitch Info’s velocity numbers on here, but they’re divergent as well: these cutters are blazing, checking in at 92.3 mph, and the sliders are much faster than the first classification set, checking in at 86 mph.

What’s happening here is that the two systems don’t know what to do with Darvish’s array of breaking balls. Say, for the sake of argument, that Darvish throws seven different breaking balls, each with a different velocity and movement profile. Try to classify those using three buckets: cutter, slider, and curveball. Good luck! Here’s a pitch that Baseball Info Solutions, which doubles as our generic “Pitch Types” data source, classified as a cutter last night:

Looks like a cutter to me, or maybe a four-seamer that he over-cut inadvertently. It has a hair of glove-side break, which moves it from where O’Hearn thinks he’s swinging — middle-in fastball, a juicy first pitch target — to where he’s actually swinging, directly over the inside corner. At 93 mph, that’s a nasty pitch, no doubt, and it’s also pretty clearly a cut fastball. Darvish, who throws his four-seam fastball in the 95-96 mph range, is hardly throwing a 93 mph slider.

That was a gimme. How about this one?

Victor Caratini’s overzealous framing aside, that looks like a pretty different pitch to me. It’s slower, and bendier; if the last pitch had a hair of break, this one has an entire bearskin rug. It doesn’t have that cutter-esque ride, either. Just one problem: Darvish, by his own admission, throws two types of cutters. So maybe that’s a cutter too.

And what about this one?

Aside from Caratini’s framing paying off, that looks like a completely different pitch. It has as much vertical break as horizontal, and it’s 10 mph slower than the first cutter we looked at. Maybe this one’s a slider, then.

But what about this one, literally the previous pitch?

That’s even slower, but it has less drop; that looks more like a textbook slider, mostly glove-side break, though not a ton of break at that. East-West movement in the low 80s? Sounds like a slider to me. Before you go calling that a slider, though, consider this pitch, which was classified as a slider:

Gravity took this one far more than the last one, despite almost identical velocity. How can those two be the same pitch? And don’t go calling it a curve, either, because I’ve got one of those to show you, and it’s more North-South despite similar velocity:

And of course, Darvish throws two different types of curves — three, really, though we haven’t seen the extremely slow curve/eephus yet this year. Take a look at this majestic lollipop:

I just showed you seven different pitches. None of them were obviously the same if you look at the three critical elements of a pitch: velocity, vertical break, and horizontal break. Try fitting them into three buckets — cutter, slider, and curve — and you start to see the problems inherent in classifying Darvish’s pitches.

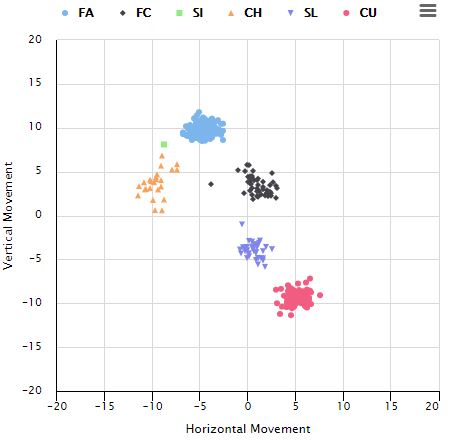

Still, even if you don’t have the right names for things, there’s often some internal logic. Take Shane Bieber’s new arsenal, for example. He calls his pitches a cutter, slider, and curve. I looked at them and saw two curves and a slider. We’ve since reclassified the “hard slider” to a cutter and the “hard curve” to a slider, which gives you this graph for all of his pitches in 2020:

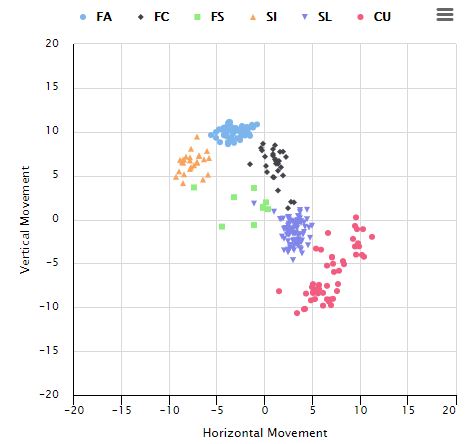

If you ignore the colors and shapes, there are five distinct spots. Quibble all day about what to call them — and we here at FanGraphs love to quibble, don’t get me wrong — but Bieber does five distinct things to the ball when he throws it, and that moves it into five distinct areas. Here’s Darvish’s 2020 chart:

This uses the Pitch Info classifications from above, which is why there are more “sliders” than “cutters,” but c’mon. These dots overlap. The edges bleed together, and there’s less center of mass. Some of the splitters are in the sinker quadrant, some in the slider quadrant. The cutters are everywhere, with some rising and some falling. The curveballs could easily be two pitches, and some could be sliders. Some of the curveballs have vertical movement if you don’t account for gravity!

When I set out to write this article, I wanted to talk about how Darvish was willing to throw any pitch in any count. The league as a whole decreases its fastball usage (excluding cutters) by five percentage points on two-strike counts. Darvish has thrown his more often with two strikes this year, 32.3% against 31% in all other counts. Take 0-0 out of the equation, and it’s even stranger: Darvish throws 43% fastballs to start an at-bat, then 24.5% fastballs until he hits two strikes, then 32.3% fastballs.

As I mulled over what to call each pitch and where to draw bright lines in describing his pitch usage, however, I changed my mind. Darvish isn’t exactly going against the grain, using his curveball when others would use their fastball and his slider when others would use their changeup. He changes each of his pitches so much, more run here or drop there, that while he does sometimes pitch against the grain, he sometimes throws a slider in a slider count and is still bucking convention, easier to do when you have fifteen sliders or whatever.

So in the end, forget all that noise. This isn’t an article about why Yu Darvish is great, at least not one of those nuts-and-bolts analytical articles where I show you the new pitch, show you how he’s using it in an interesting way, and then show you how that reduces hitters to a quivering mess in the batter’s box while unlocking fame and fortune for the pitcher.

This is an article about how fun it is to watch Darvish pitch and try to name the pitch he’s throwing. It’s wild. When he’s on, he can command them all at will — and as his 3.1% walk rate will tell you, he’s on right now. This form of Darvish is both dominant and delightful. Through three starts, he has a 2.12 ERA and a 1.63 FIP (2.99 xFIP). He has the second-most WAR among all pitchers this year, behind only Bieber. And yet, that’s not the fun part. The fun part is when he does this:

Which is a nasty enough pitch on its own, 97 on the black with some arm-side run to paint the corner, even if he missed Caratini’s target. But it’s not just that; it’s that in the same outing, he’s liable to do this:

And batters are so geared up for so many things that they just sometimes let it go by. Anyone can throw a 90 mph cutter that backs up and spins instead of breaking. When Darvish does it, though, you think hey, wait, maybe that was on purpose. Baseball is fun when you can analyze it, but it’s also fun when you’re left wondering, and no pitcher in baseball leaves me gleefully wondering more than Darvish right now.

2020’s Most Irreplaceable Players

The 2020 major league season is about 20% done, which might feel strange given that the season isn’t quite two weeks old, but it’s just one of the many odds things about this year. We’re just three weeks from the trade deadline and the basic contours of who the contenders and the also-rans are has become clear in a shockingly small number of games. That shortened slate has also seen a number of key players go down with significant injuries. The threat of COVID-19 looms large over any discussion of missed time this season, but sadly, more familiar maladies will also take their toll — Justin Verlander is still weeks from a potential return from a right forearm strain, Shohei Ohtani likely won’t pitch again this season after leaving Sunday’s game with a forearm strain of his own, and Mike Soroka joined the list with a painful tear to his Achilles tendon Monday evening, ending his 2020 season before it had really begun. Even Max Scherzer exited Wednesday night’s action with a sore hamstring, though thankfully it appears minor.

How big a loss for the Braves was Soroka? With him still in the rotation, the ZiPS projection system had the Atlanta Braves with an 89.5% chance of making baseball’s expanded 16-team playoffs. Without Soroka, that number drops to 81.5%, nearly doubling the probability that Atlanta watches the playoffs from home. How does that eight percentage points rank among baseball’s stars? As I do every season, I asked ZiPS to re-project league standings with individual star players removed from their team’s rosters.

This isn’t a WAR ranking, which would be kind of boring. Teams whose playoff fortunes are most up in the air, especially those without sufficient depth, tend to be the ones that get in the most trouble when they lose a key player due to injury. The combination of good early results and deep rosters has left a few teams at the top of the food chain — the Braves, Dodgers, Athletics, Twins, and Yankees — without a single player in the top 25 in playoff leverage. That’s not to say that losing Mookie Betts or Cody Bellinger wouldn’t be a huge loss for the Dodgers, but the team has good backup options and it would take losing both to seriously change the team’s playoff odds.

With Wednesday night’s games in the books, here are the ZiPS-projected playoff probabilities for every team:

| Team | Playoff Probability |

|---|---|

| Los Angeles Dodgers | 97.4% |

| New York Yankees | 94.3% |

| Minnesota Twins | 90.7% |

| Chicago Cubs | 85.4% |

| Oakland Athletics | 81.9% |

| Atlanta Braves | 81.5% |

| Houston Astros | 77.5% |

| Cleveland Indians | 76.6% |

| San Diego Padres | 74.3% |

| Tampa Bay Rays | 72.4% |

| Chicago White Sox | 69.1% |

| Washington Nationals | 69.1% |

| Philadelphia Phillies | 56.0% |

| Cincinnati Reds | 53.1% |

| Milwaukee Brewers | 52.6% |

| St. Louis Cardinals | 52.2% |

| Los Angeles Angels | 49.6% |

| Colorado Rockies | 45.6% |

| New York Mets | 45.0% |

| Toronto Blue Jays | 44.2% |

| Boston Red Sox | 42.4% |

| Arizona Diamondbacks | 31.8% |

| Texas Rangers | 27.2% |

| Miami Marlins | 24.1% |

| Detroit Tigers | 23.2% |

| San Francisco Giants | 22.9% |

| Kansas City Royals | 18.6% |

| Seattle Mariners | 17.1% |

| Baltimore Orioles | 15.1% |

| Pittsburgh Pirates | 8.9% |

Dan Szymborski FanGraphs Chat – 8/6/20

| 12:06 |

: And begun, the chat has!

|

| 12:06 |

: Once it starts, it can’t stop.

|

| 12:06 |

: Until 1 PM!

|

| 12:06 |

: Well I guess it could.

|

| 12:06 |

: If I have a stroke or something, I’m calling 911, not chilling with you guys.

|

| 12:06 |

: Kyle Lewis is awesome still!!

|

Introducing the 1ABHR Club, Part II: Let’s Go to the Videotape!

Al Woods is hardly a household name, but know this: Among members of the 1ABHR Club, reserved for those who go yard in their first big league at-bat (see Part I), he is the first to have his debut tater appear on YouTube.

Unwittingly, Woods introduced us to a time when we can relive both the visual drama and the verbal banality produced by the first-AB dinger. Before the cliches take hold, though, there is always the pioneering moment, wholly original and unspoiled by the triteness it fathers. This was — and is — Woods’ dinger on April 7, 1977. Not only was it Woods’ debut. Not only was it Opening Day for his Blue Jays. It was the first game the Jays ever played.

Roll tape: With Toronto leading the White Sox, 5-4, in the sixth, pinch-hitter Woods has worked the count to 1-and-2 against starter Francisco Barrios.

Crack!

Announcer: “Hit hard! Right field!”

Back goes Richie Zisk, to a wall made of blue trash bags.

Announcer: “Home run!”

The 22-second clip immediately jumps to Woods’ crossing home plate. Soon thereafter it ends, unceremoniously, with no hint of the hokum that will characterize the clips of many of his 1ABHR descendants. There is no mention of his getting the ball back, no camera shot of family and friends high-fiving. There is no silent treatment, no curtain call. Read the rest of this entry »

Dodgers’ Dustin May Is Dazzling

Dustin May is ready for prime time. The 22-year-old righty wasn’t even supposed to be part of the Dodgers’ rotation at the outset of the season, but he’s taken the ball three times thus far, including an emergency start on Opening Day. So far, he’s not only shown why he’s one of the game’s top pitching prospects but why he’s already worth making time to watch, and not just because the 6-foot-6 righty with the distinctive ginger mop top and the high leg kick is one of the most instantly recognizable players in the game.

On Tuesday night against the Padres in San Diego, May delivered the longest start of his young career, a six-inning effort; he fell one out short in each of his first three turns upon being called up last August. He allowed just three hits and two runs, the first in the third inning after hitting Francisco Mejía with a pitch and then surrendering a two-out double to Fernando Tatis Jr., and the second via a fourth-inning solo homer by Jake Cronenworth. At that point, he was in a 2-0 hole, but the Dodgers’ offense bailed him out, scoring three runs in the sixth and seventh innings en route to a 5-2 win.

May collected a career-high eight strikeouts against the Padres, the second of which — against Manny Machado in the first inning — set Twitter ablaze:

Dustin May, Ungodly 99mph Two Seamer. ? pic.twitter.com/uUeINZbKBq

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) August 5, 2020

Introducing the 1ABHR Club, Part I

For the man from Castro’s Cuba, it happened at Great American Ball Park.

On August 2, 2012, in Cincinnati, Eddy Rodriguez departed the Padres on-deck circle and made his way to a big league batter’s box for the first time in his seven-year pro career. His larger journey had been less direct. Two decades earlier, seven-year-old Eddy had boarded his father’s rickety fishing boat and with dad Edilio, mom Ylya, and sister Yanisbet embarked on the 100-mile route from the northern shores of the communist country to the southern shores of the United States. En route, the family encountered 20-foot waves and a useless compass. The boat nearly capsized, threatening to send them to the sharks. By day three, they were low on fuel, water and food. Soon they had nothing but coffee beans. They ate them.

Desperate, they tied a white sheet to a pole.

In time, the U.S. Coast Guard arrived.

Now here he was, called up from the Single-A Storm just four months shy of his 27th birthday, getting his shot against Reds ace Johnny Cueto. On a 1-2 count, and with nearly 23,000 fans watching from the seats and many more on TV, Rodriguez drove a Cueto curveball “high and deep to left-centerfield!”

Just as it slammed into a seat 416 feet from home plate, announcer Dick Enberg added, “Rodriguez will touch ‘em all in his first big league at-bat!”

In that instant, Rodriguez had become the 112th player in big league history to join what I deem the 1ABHR Club. It looks like a vanity plate. It should be.

It’s an exclusive group. Through the end of the 2019 season, 10 additional players had homered in their first at-bat to put membership at 122; one more has joined so far in 2020. What binds these players is the singularity of their feat. Babe Ruth? Not a member. Bill Duggleby? A pioneering member.

On April 21, 1898, the man they called Frosty Bill hit a Cy Seymour fastball “right on the pickle,” the Philadelphia Inquirer reported, and sent it out of Philadelphia’s Baker Bowl for a grand slam. Not for another 107 years would a player belt a granny in his first big league at-bat. What made Frosty Bill’s four-bagger all the more remarkable is that he was a hurler, one of 20 now in the club.

Forty-one seasons hence, Boston left-hander Bill LeFebvre stepped in for his first at-bat and drove Monty Stratton’s first pitch to the Green Monster. As he approached second base, LeFebrve saw the ball carom onto the field. Head down, he rounded second and slid into third for a triple. Read the rest of this entry »

Mike Yastrzemski, Patient Thumper

There weren’t a lot of bright spots on the 2019 San Francisco Giants. Pablo Sandoval was fun here and there, particularly when he pitched. Alex Dickerson hit a few dingers. Donovan Solano isn’t cooked just yet. For the most part, though, those were marginal. The real splash, the only real splash, was Mike Yastrzemski, who went from feel-good legacy to bona fide major league outfielder in the course of one slugging season.

2019 was already surprising enough for the career minor leaguer. After showing flashes of patience, power, and a feel to hit in previous seasons, he put them all together in Triple-A Sacramento, and there was no one blocking him from the majors. Four hundred plate appearances and a .272/.334/.518 batting line later, he was the best outfielder on the team, and the Giants were constructing their 2020 roster with one spot on the depth chart written in pen.

If the start of 2020 is any indication, however, last year wasn’t Yastrzemski’s ceiling. His ceiling is this year’s white-hot start: .310/.473/.643 with three homers, good for a 204 wRC+. Oh yeah — he’s playing freaking center field every day, too. Twelve games does not a season make, but if you could make his whole season out of the last two weeks, he’d basically be Mike Trout — an up-the-middle defender with a 200-ish wRC+.

Is he a good fielder? It’s unclear. He looked good both by the eye test and by the advanced statistics troika of DRS, UZR, and OAA last year in the corners, and looks at least reasonable in center so far this season. He’s not a long-term premium defender — he’s nearly 30, for one thing, and has only average straight-line speed — but tuck him in a corner, and he’ll be inoffensive at worst and an asset at best.

But the exciting part about Yastrzemski isn’t the fielding, at least not mostly. It’s the offensive value, the leading-baseball-in-WAR offensive explosion that makes Giants fans mostly shrug their shoulders but also rub their hands together greedily when they think no one’s looking. Sure, it’s early. Sure, it’s not our year. But it could be real, right? The team could have found a new superstar, right? Read the rest of this entry »

Another Nice Thing We Can’t Have in 2020: Shohei Ohtani’s Pitching

The list of things that haven’t gone according to plan in 2020 is long enough to reach to the moon and back, and to that, we can add the return of Shohei Ohtani to competitive pitching. After more than a year spent recovering from Tommy John surgery, the 26-year-old wonder’s reacquaintance with the mound was hotly anticipated, but after two brief and miserable outings, he’s injured, and Angels manager Joe Maddon said on Tuesday that he doesn’t expect to see Ohtani pitch again this year.

On Sunday, Ohtani made his second start of the season, and it began with promise, as he retired the top of the Astros’ lineup — George Springer, Jose Altuve, and Alex Bregman — in order on a total of eight pitches. He topped 95 mph a few times with his four-seamer, struck out Springer swinging at a splitter, and induced Altuve to pop up a bunt foul. Here’s the Springer strikeout:

Dan Szymborski

Dan Szymborski