The Yankees’ 8-3 loss in Game 4 of the ALCS did not eliminate them, but between their missed opportunities early (stranding five runners in scoring position in the first five innings) and their sloppiness late (four errors over the final four innings), the game had an air of finality about it. Nowhere was that more true than in the case of CC Sabathia, who departed due to a shoulder injury in what will stand as the final appearance of a 19-year major league career that may well be capstoned by a plaque in Cooperstown.

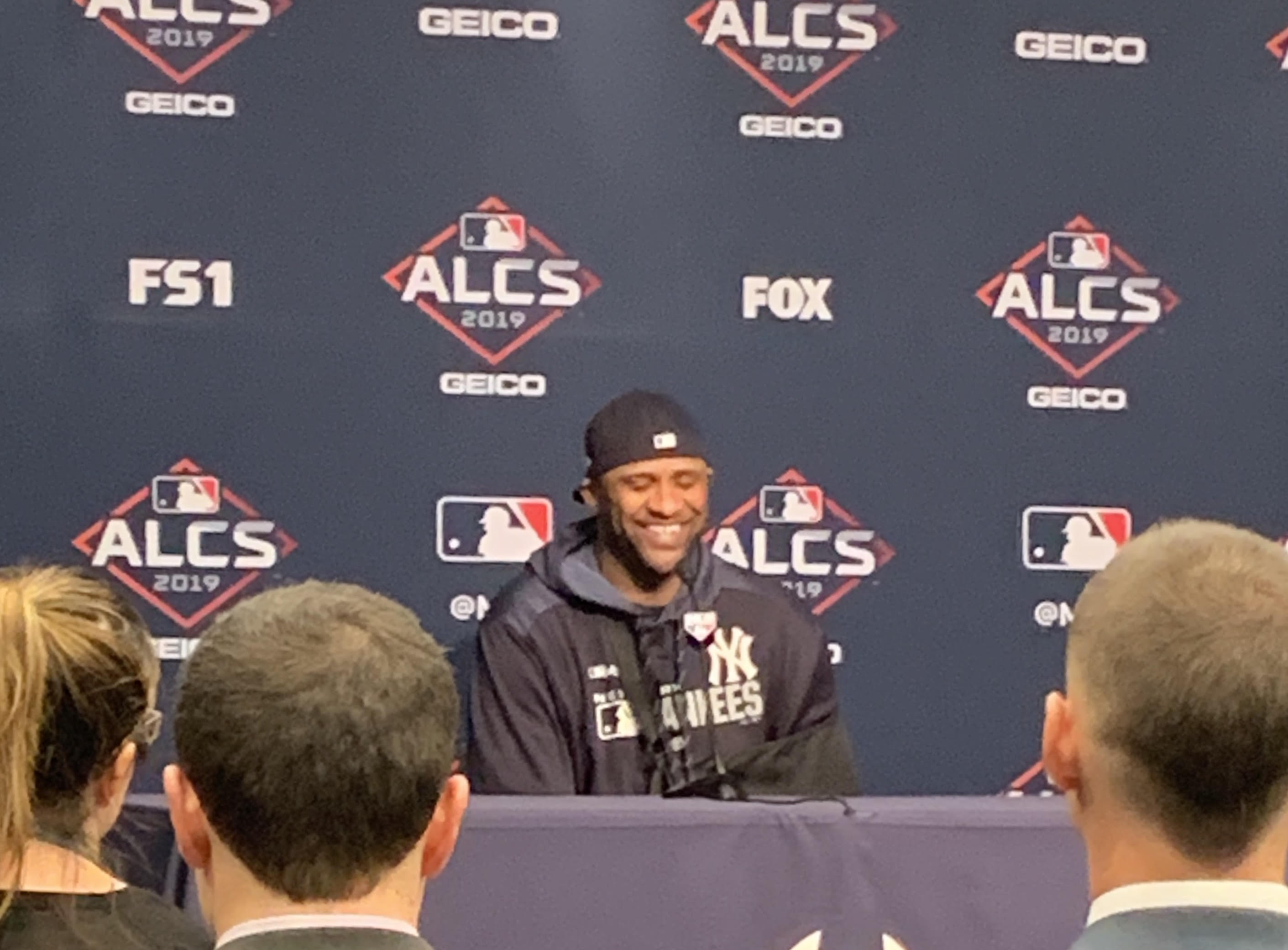

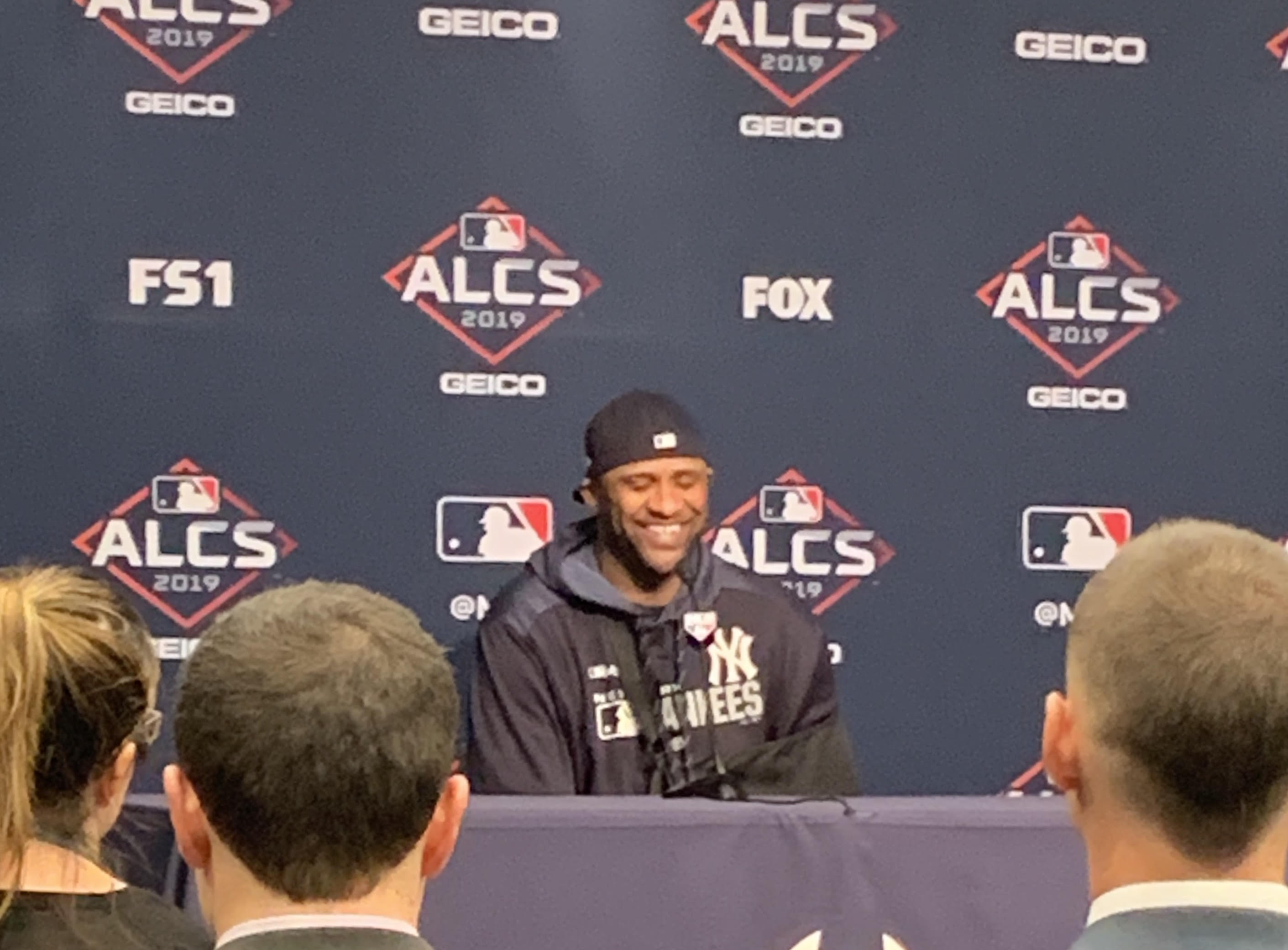

On Friday morning, the Yankees announced that Sabathia had experienced a subluxation of his shoulder joint and replaced him on the roster with righty Ben Heller. The move means that he would not be allowed to be reactivated for the World Series, almost certainly a moot point given the condition of his shoulder, to say nothing of the Yankees’ precarious position. Sabathia, who appeared to be in good spirits during a pregame press conference on Friday despite pain that he described as “pretty intense,” said that he would “maybe get an MRI after we get back from Houston” and that he doesn’t know yet whether he will need surgery.

Dropped into a difficult situation in his second relief appearance of the series and just the fourth of his career — runners on second and third with no outs in the top of the eighth, with the Yankees already down 6-3 — Sabathia was victimized by the first of Gleyber Torres‘ two errors when Yordan Alvarez’s chopper deflected off the second baseman’s right hand as he positioned himself to throw home; Alex Bregman scored on the play, and Alvarez was safe at first. After retiring Carlos Correa on a soft liner to right field, one in which Aaron Judge nearly doubled Yuli Gurriel off second base, Sabathia hit Robinson Chirinos on the left elbow with a pitch, loading the bases. He got Aledmys Diaz to pop up to shallow right, keeping Gurriel from scoring, but after missing inside on a 1-1 cutter to George Springer, Sabathia grimaced, and both manager Aaron Boone and head athletic trainer Steve Donohue came to the mound.

According to Sabathia, his shoulder popped during his last pitch to Diaz: “I just felt like when I released the ball, my shoulder kind of went with it.” In other words, he pitched through a partial separation when he faced Springer, throwing a first-pitch cutter that reached 91.2 mph.

After throwing one warm-up pitch to check if he could continue, Sabathia told Boone and Donohue, “I’m done,” shook his head, and then departed to a heartfelt ovation from the Yankee Stadium crowd as well as both dugouts. The FS1 broadcast showed both Springer and Gerrit Cole paying their respects, then a slump-shouldered Sabathia covering his face with his glove, understandably overcome with emotion but — and maybe this is just a scribe projecting — ever so slightly tipping his cap to the crowd even as he did. It wasn’t easy to watch, and you’re by no means obligated to, but here’s the whole scene: Read the rest of this entry »