We’ve Reached Peak Position Players Pitching

On Monday, Rays’ infielder Michael Brosseau took the mound. On Sunday, it was Brewers infielder Hernán Pérez, and before him, Diamondbacks catcher Alex Avila on Saturday, and Reds infielder Jose Peraza on Friday. On Thursday, which now seems so long ago — seriously, do you remember what you had for dinner that night? — it was Yankees first baseman Mike Ford. If you think that home run and strikeout rates have gotten out of hand, consider the tally of position players pitching.

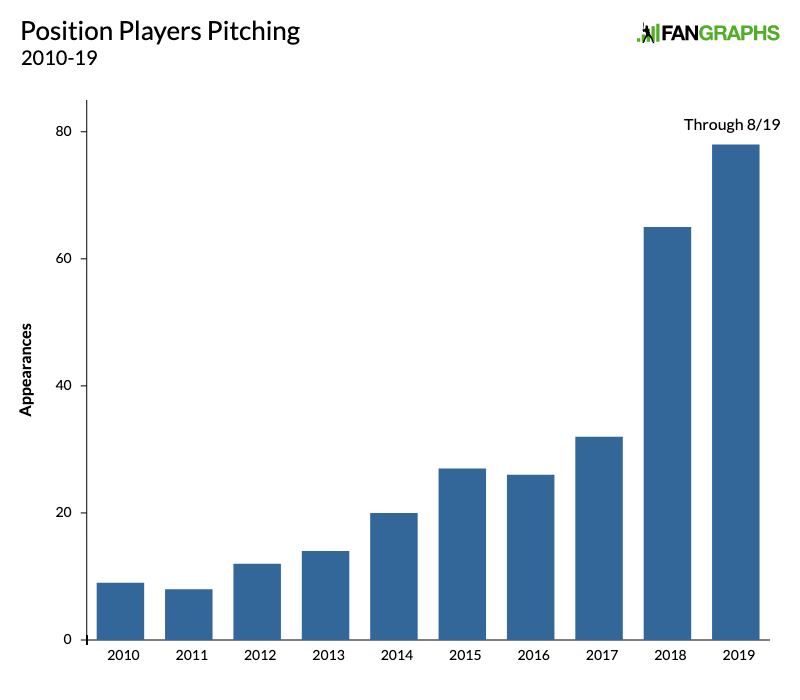

While teams are producing homers at a per-game rate 12% higher than the previous record (set in 2017), and while per-game strikeout rates are on the rise for the 14th straight season (up about 3% relative to last year), the single-season record for position player outings (65, set just last year, and no, that count doesn’t include Shohei Ohtani) fell earlier this month. Already, position players have taken the hill a total of 78 times this season; prorated to a full schedule, that’s 101 outings, a 55% increase on last year. And if things were to continue at the blistering pace we’ve seen since the All-Star break — 33 appearances in 39 days — the number would soar higher than the drive the Indians’ Carlos Santana hit off Ford:

Whew. Traditionally, a position player pitching appearance has been a break-glass-in-case-of-emergency desperation move (generally in extra innings) or a lighthearted farce that draws attention away from an otherwise unpleasant blowout. Through some combination of higher-scoring games, higher per-game totals of relievers, concerns about reliever workloads, and the reduced stigma of this particular maneuver, the rate of such appearances has accelerated. Like the barrage of homers and strikeouts, whether or not the higher frequency takes the fun out of it is rather subjective. To these eyes, the novelty is in the absurdity, like imagining a dog penning this article, and the bordering-on-routine nature of this year’s appearances has dimmed some of the luster. Even so, it’s an interesting enough subject to dwell upon for a few minutes.

For starters, here’s the progression for the past decade: