A Candidate-by-Candidate Look at the 2026 Hall of Fame Election Results

The following article is part of Jay Jaffe’s ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2026 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to this year’s ballot, and other candidates in the series, use the tool above; an introduction to JAWS can be found here. For a tentative schedule, see here. All WAR figures refer to the Baseball Reference version unless otherwise indicated.

The 2026 Hall of Fame election is history, with a pair of center fielders who were born one day apart, fourth-year candidate Carlos Beltrán (born April 24, 1977) and ninth-year candidate Andruw Jones (born April 23, 1977), elected by the Baseball Writers Association of America. This is the fourth time two players from the same position besides pitcher were elected by the writers in the same year. Right fielders Harry Heilmann and Paul Waner were the first pair in 1952, followed by right fielders Henry Aaron and Frank Robinson in ’82, with left fielders Rickey Henderson and Jim Rice elected in 2009. That’s some impressive company!

Beltrán and Jones will be inducted into the Hall along with Contemporary Baseball honoree Jeff Kent on July 26, 2026, on the grounds of the Clark Sports Center in Cooperstown, New York. There’s no official word yet on which caps the players will be wearing on their plaques — the Hall has the final word — but odds are they’ll be the ones that you expect. Said Beltrán, who’s currently a special assistant for the Mets, “There’s no doubt that the Mets are a big part of my identity.” Kent has expressed his desire to wear a Giants cap, and Jones is almost certain to wear a Braves cap.

As usual, beyond the topline results, there’s plenty to digest from Tuesday’s returns. So as promised, here’s my candidate-by-candidate breakdown of the entire slate of 27 candidates, 13 of whom will return to the ballot next year. Note that references to percentages in Ryan Thibodaux’s indispensable Tracker may distinguish between what was logged at the time of the announcement at 6 p.m. ET on Tuesday (245 total ballots) and what’s in there as of Thursday at 9 a.m. ET (254 total ballots) Read the rest of this entry »

Luis Arraez Belongs on the Mountaintop

In early November, MLB Trade Rumors and Baseball Prospectus released their top 50 free agents lists, which included guesses about where each player would end up. Our focus in this article is on Luis Arraez, and in those two lists, seven very smart people and one random number generator made their best estimations about his likeliest destination. Only two of those experts picked the same team for him. The next week, MLB.com’s Mike Petriello broke down a whopping seven potential landing spots for Arraez. Only one of those teams was on either of the two previous lists. Lastly, just this weekend, a Fox Sports article with no byline explained why three teams would make the best fit for Arraez, and only one of those teams had any overlap with the previous three articles. By my count, that’s eight different experts, one robot, and one I-don’t-know-what making a total of 18 predictions. Somehow, those 18 predictions included 15 different landing spots for Arraez. That’s half the league! Only three teams got multiple votes, and no team got more than two. We’ve got a genuine mystery on our hands.

To some degree, all of this is understandable. Most projections have Arraez signing for either one year or two with an average annual value of $11 or $12 million. That means even the stingiest teams can afford him. And although Arraez is a poor defender who only projects for roughly 1.5 WAR (depending on your projection system), he’s never once put up a below-average season on offense. With the possible exception of the Dodgers, there is no such thing as a team that couldn’t find a spot for a hitter of Arraez’s caliber. ZiPS is slightly higher on Arraez than most systems, projecting him for 1.8 WAR in 2026. That’s more than we have projected in our Depth Charts either at first base, DH, or both for 21 different teams. Everybody can afford him. Almost everybody could use him. He really could end up anywhere.

While I don’t have any special insight about where Arraez will end up, I do have a strong preference. I want him to sign with the Rockies, and I want this for a very simple reason. I want to see Luis Arraez be the most Luis Arraez he can be. His skill set is unique in today’s game, and Coors Field is the perfect environment to let him flourish. Read the rest of this entry »

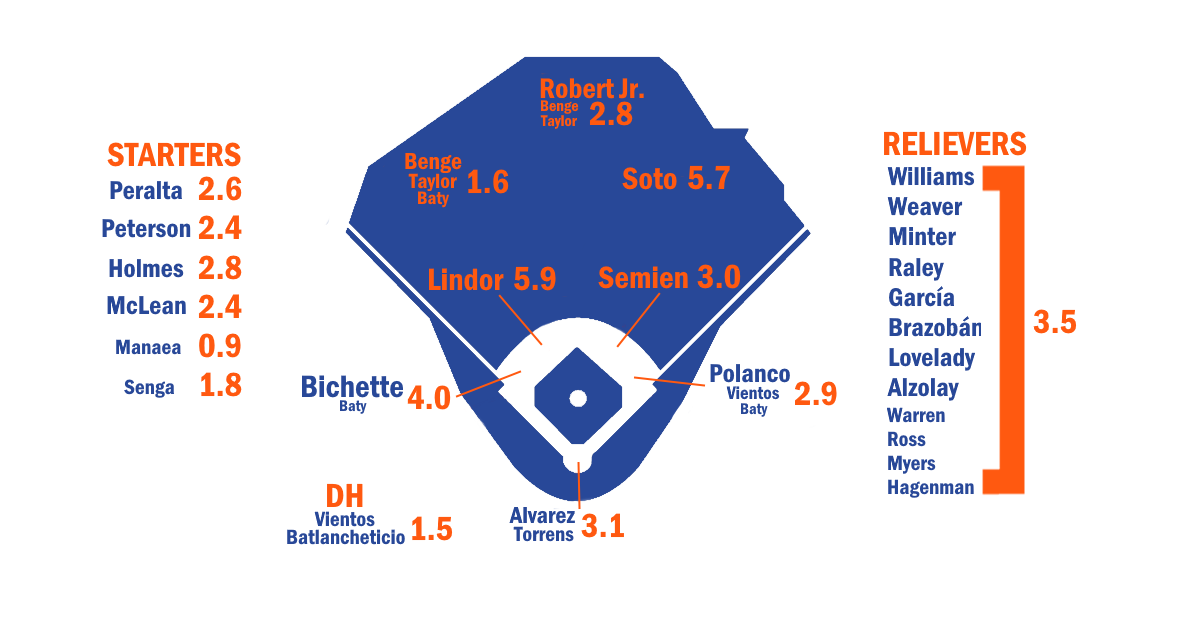

2026 ZiPS Projections: New York Mets

For the 22nd consecutive season, the ZiPS projection system is unleashing a full set of prognostications. For more information on the ZiPS projections, please consult this year’s introduction, as well as MLB’s glossary entry. The team order is selected by lot, and the penultimate team is the New York Mets.

Batters

The Mets are a bit like an intellectual character in a 19th Century Russian novel. They’re well-read enough to understand why life just isn’t working, and while they make changes every winter, it always seems to come with the precognition that something will go horribly wrong, and there’s little recourse but to observe their own downfall. Yankees fandom is more transactional, and depending on how the season turns out, you either cheer the empire or curse Brian Cashman. Rooting for the Mets is existential; you go into every season with hope, but an unquenchable feeling that something will go horribly or maybe even comically wrong. Meaning as a Mets fan does not come from celebrating the team’s achievements, but the act of enduring and returning, year after year, with the knowledge that preparation offers no escape. Mets fans essentially become annotators of doomed worlds.

If every moment of Mets triumph is matched with an equal measure of Mets tragedy, the lineup may be in for some dark times when the worm turns. I actually think I’d rather have Pete Alonso for his deal than Jorge Polanco for his if I were the Mets, but the projections suggest that I might be wrong. Either way, this lineup looks extremely solid as a whole. Starting with two players, Juan Soto and Francisco Lindor make up for a lot of sins. But there aren’t really a lot of sins in the lineup. ZiPS thinks Bo Bichette is more valuable at third base than he was at shortstop, and he certainly has All-Star potential. ZiPS also forecasts decent bounce-back seasons for offseason trade acquisitions Luis Robert Jr. and Marcus Semien. Francisco Alvarez is coming off a near .800 OPS season, and under the new rules encouraging stolen bases, Luis Torrens’ value has increased because of his ability at preventing them, making him more than capable at holding up the lighter end of a catching tandem.

The DH situation isn’t amazing, with Mark Vientos getting the bulk of the plate appearances there, but only a few teams really get a ton of WAR from that spot anyway. Carson Benge certainly has upside, and while it’s not a particularly exciting projection, it’s not a bad forecast for a guy who hasn’t hit Triple-A pitchers yet. Brett Baty showed in 2025 that he can hit well enough to provide solid depth for the Mets. Jett Williams was also good depth in the infield, but he didn’t have a clear path to actual playing time in the majors in 2026 outside of a reserve role, so the Mets sent him to Milwaukee on Wednesday night as part of a trade to the get right-handed pitchers Freddy Peralta and Tobias Myers.

Pitchers

ZiPS expects the Mets’ pitching to be pretty good, giving the staff a bit of a bump from last year’s preseason projections. And that was before the trade for Peralta, who was the Brewers’ the most valuable pitcher. While Peralta’s not really a sub-three ERA guy — ZiPS thinks he’s legitimate a low-BABIP pitcher, but .243 is damned hard to maintain — he’s still an excellent pitcher who is a huge addition to New York’s rotation. Clay Holmes isn’t an ace, and he bled a couple strikeouts when he transitioned from the bullpen to the rotation, but his 2025 also demonstrates that his conversion to starting wasn’t just a mad scientist’s latest crazy plan. Nolan McLean looks like a much stronger bet going into 2026 than he did at this time last year, and while Jonah Tong didn’t have instant success in the majors, he also greatly boosted his stock, though we may not see a lot of it in the majors in 2026 unless the team is hit by injuries. Last year, David Peterson didn’t match his 2.90 ERA from 2024, but that never should have been the expectation anyway, and he’s a fairly dependable no. 2 starter type. Kodai Senga’s return went generally well, aside from nobody checking how the ghost fork graphic at the stadium would interact with a strikeout tally.

Sean Manaea ought to get back to effectively eating innings in 2026, and though he’s certainly not the headliner, the acquired Myers is a reasonable option to have in reserve. ZiPS is less excited once we get past Myers, to guys like Christian Scott and Cooper Criswell. But on the plus side, ZiPS thinks there’s a real chance that Jonathan Pintaro’s command will improve just enough for him to have a breakout in 2026.

ZiPS views the Mets as having an above-average bullpen, but one that’s below baseball’s elite. Maybe it’s just cognitive dissonance on my part, but I still have some worries about Devin Williams despite all the objective data suggesting he’s a great bounce-back candidate. And he is, but 2025 will still be in the back of my mind plus, you know, the Mets. Luke Weaver is a good bullpen no. 2 and fallback closer option, and A.J. Minter was at his Mintest last season. Brooks Raley gets a strong projection as well, and ZiPS is unaware of my extreme bias in favor of side-armers; Raley is more low three-quarters, but he’s at least side-arm adjacent. Criswell gets a significantly better projection as a reliever than as a starter. My silicon counterpart is rather meh on the rest of the bullpen, except for maybe Huascar Brazobán, but it still looks like a highly cromulent unit.

Despite last season’s collapse, ZiPS projects the Mets as a highly competitive team in the NL East, and one the league shouldn’t dismiss. Now, come September, six Mets could need Tommy John surgery, or maybe Juan Soto and Francisco Lindor are destined to get trapped inside a leatherbound book given to Carlos Mendoza by a library maintenance worker who looks suspiciously like M.R. James. But predictive algorithms and fuzzy clustering methods allow us to peek only so far behind the veil of fate.

Ballpark graphic courtesy Eephus League. Depth charts constructed by way of those listed here. Size of player names is very roughly proportional to Depth Chart playing time. The final team projections may differ considerably from our Depth Chart playing time.

| Player | B | Age | PO | PA | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | BB | SO | SB | CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juan Soto | L | 27 | RF | 670 | 538 | 109 | 146 | 23 | 1 | 37 | 103 | 124 | 116 | 23 | 3 |

| Francisco Lindor | B | 32 | SS | 672 | 596 | 102 | 157 | 30 | 1 | 27 | 90 | 58 | 121 | 23 | 4 |

| Bo Bichette | R | 28 | 3B | 598 | 555 | 73 | 163 | 31 | 1 | 17 | 80 | 37 | 97 | 5 | 4 |

| Marcus Semien | R | 35 | 2B | 581 | 521 | 80 | 127 | 21 | 2 | 17 | 69 | 52 | 93 | 9 | 2 |

| Brett Baty | L | 26 | 3B | 471 | 426 | 59 | 107 | 16 | 1 | 19 | 61 | 39 | 115 | 5 | 1 |

| Francisco Alvarez | R | 24 | C | 441 | 392 | 53 | 92 | 15 | 1 | 21 | 64 | 41 | 118 | 1 | 0 |

| Jorge Polanco | B | 32 | 1B | 473 | 419 | 56 | 106 | 18 | 0 | 21 | 69 | 45 | 93 | 4 | 2 |

| Luis Robert Jr. | R | 28 | CF | 470 | 428 | 59 | 102 | 19 | 0 | 18 | 69 | 35 | 127 | 24 | 6 |

| Mark Vientos | R | 26 | 3B | 527 | 480 | 59 | 121 | 22 | 2 | 22 | 77 | 37 | 137 | 1 | 0 |

| Jacob Reimer | R | 22 | 3B | 518 | 461 | 74 | 108 | 27 | 3 | 15 | 70 | 41 | 123 | 6 | 2 |

| Ronny Mauricio | B | 25 | 3B | 460 | 429 | 54 | 104 | 18 | 1 | 15 | 53 | 27 | 117 | 13 | 4 |

| Jose Siri | R | 30 | CF | 358 | 327 | 50 | 66 | 14 | 1 | 14 | 47 | 23 | 131 | 12 | 3 |

| Carson Benge | L | 23 | CF | 522 | 464 | 72 | 114 | 22 | 5 | 13 | 65 | 48 | 110 | 11 | 3 |

| Luis Torrens | R | 30 | C | 271 | 249 | 24 | 62 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 30 | 17 | 60 | 1 | 1 |

| Ji Hwan Bae | L | 26 | CF | 399 | 358 | 63 | 91 | 17 | 4 | 4 | 42 | 35 | 93 | 20 | 6 |

| Chris Suero | R | 22 | C | 487 | 422 | 62 | 86 | 14 | 1 | 13 | 60 | 47 | 150 | 14 | 6 |

| Jared Young | L | 30 | LF | 407 | 359 | 51 | 87 | 16 | 2 | 15 | 57 | 38 | 96 | 5 | 2 |

| Ryan Clifford | L | 22 | 1B | 587 | 511 | 63 | 109 | 22 | 1 | 25 | 79 | 66 | 174 | 4 | 2 |

| Jackson Cluff | L | 29 | SS | 365 | 319 | 44 | 65 | 13 | 2 | 8 | 40 | 35 | 118 | 11 | 2 |

| David Villar | R | 29 | 1B | 401 | 354 | 48 | 78 | 15 | 0 | 13 | 49 | 39 | 114 | 2 | 1 |

| Jesse Winker | L | 32 | DH | 364 | 307 | 39 | 72 | 13 | 1 | 9 | 39 | 49 | 77 | 4 | 1 |

| Tyrone Taylor | R | 32 | CF | 339 | 312 | 41 | 72 | 18 | 2 | 7 | 33 | 16 | 76 | 9 | 2 |

| Wyatt Young | L | 26 | 2B | 439 | 386 | 48 | 89 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 34 | 43 | 99 | 7 | 3 |

| Yonny Hernández | B | 28 | 2B | 400 | 353 | 47 | 85 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 32 | 33 | 61 | 9 | 6 |

| A.J. Ewing | L | 21 | CF | 592 | 537 | 81 | 135 | 23 | 8 | 4 | 57 | 47 | 127 | 36 | 8 |

| Chris Williams | R | 29 | C | 321 | 283 | 35 | 55 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 37 | 32 | 116 | 1 | 0 |

| Kevin Parada | R | 24 | C | 440 | 399 | 41 | 87 | 18 | 1 | 12 | 51 | 30 | 140 | 2 | 1 |

| Jose Rojas | L | 33 | DH | 434 | 389 | 48 | 85 | 20 | 2 | 18 | 60 | 39 | 106 | 5 | 1 |

| Gilberto Celestino | R | 27 | RF | 385 | 347 | 42 | 82 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 35 | 35 | 90 | 6 | 2 |

| Starling Marte | R | 37 | DH | 321 | 292 | 38 | 76 | 12 | 1 | 7 | 34 | 19 | 69 | 10 | 2 |

| Christian Arroyo | R | 31 | 1B | 236 | 219 | 26 | 54 | 11 | 0 | 5 | 24 | 12 | 53 | 2 | 1 |

| Luis De Los Santos | R | 28 | 3B | 365 | 337 | 38 | 73 | 12 | 1 | 7 | 35 | 21 | 103 | 2 | 1 |

| Rafael Ortega | L | 35 | RF | 326 | 285 | 36 | 60 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 30 | 35 | 75 | 10 | 5 |

| Nick Morabito | R | 23 | CF | 499 | 454 | 59 | 109 | 18 | 2 | 4 | 47 | 36 | 123 | 27 | 9 |

| Tsung-Che Cheng | L | 24 | SS | 482 | 427 | 52 | 91 | 16 | 3 | 6 | 45 | 40 | 126 | 13 | 7 |

| Cristian Pache | R | 27 | RF | 286 | 257 | 27 | 54 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 26 | 24 | 91 | 4 | 2 |

| Niko Goodrum | B | 34 | SS | 247 | 211 | 27 | 46 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 23 | 33 | 74 | 5 | 3 |

| Jose Ramos | R | 25 | RF | 467 | 425 | 51 | 91 | 14 | 2 | 15 | 50 | 34 | 175 | 3 | 4 |

| D’Andre Smith | R | 25 | LF | 369 | 344 | 39 | 84 | 15 | 2 | 6 | 41 | 17 | 85 | 12 | 2 |

| Hayden Senger | R | 29 | C | 268 | 244 | 26 | 50 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 24 | 14 | 82 | 1 | 1 |

| Travis Swaggerty | L | 28 | LF | 215 | 193 | 23 | 38 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 20 | 69 | 4 | 2 |

| JT Schwartz | L | 26 | 1B | 385 | 345 | 36 | 77 | 16 | 1 | 5 | 39 | 30 | 77 | 1 | 2 |

| Travis Jankowski | L | 35 | CF | 193 | 170 | 24 | 37 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 19 | 39 | 9 | 1 |

| Estarling Mercado | L | 23 | 1B | 207 | 186 | 21 | 36 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 24 | 16 | 65 | 2 | 1 |

| Nick Lorusso | R | 25 | 3B | 436 | 399 | 39 | 85 | 23 | 0 | 6 | 41 | 29 | 121 | 5 | 2 |

| Marco Vargas | L | 21 | 2B | 448 | 404 | 52 | 83 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 32 | 39 | 103 | 18 | 5 |

| Eli Serrano III | L | 23 | CF | 380 | 341 | 42 | 68 | 17 | 2 | 7 | 38 | 31 | 89 | 4 | 2 |

| Onix Vega | R | 27 | C | 203 | 183 | 18 | 37 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 16 | 45 | 1 | 2 |

| Troy Schreffler Jr. | R | 25 | LF | 218 | 199 | 27 | 39 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 21 | 13 | 78 | 6 | 2 |

| Omar De Los Santos | R | 26 | RF | 324 | 303 | 40 | 60 | 8 | 3 | 9 | 35 | 14 | 135 | 21 | 7 |

| Trace Willhoite | R | 25 | 1B | 428 | 381 | 55 | 71 | 13 | 1 | 14 | 52 | 31 | 136 | 7 | 1 |

| Yohairo Cuevas | L | 22 | RF | 424 | 376 | 40 | 74 | 19 | 1 | 2 | 33 | 39 | 121 | 10 | 3 |

| William Lugo | R | 24 | SS | 438 | 398 | 39 | 78 | 14 | 1 | 8 | 41 | 32 | 128 | 3 | 1 |

| Yonatan Henriquez | B | 21 | CF | 423 | 385 | 49 | 77 | 15 | 2 | 6 | 37 | 34 | 100 | 15 | 5 |

| Ronald Hernandez | B | 22 | C | 422 | 385 | 41 | 76 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 38 | 30 | 114 | 10 | 2 |

| Diego Mosquera | R | 22 | LF | 253 | 229 | 15 | 46 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 17 | 16 | 56 | 3 | 3 |

| Boston Baro | L | 21 | SS | 451 | 420 | 45 | 88 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 37 | 25 | 104 | 13 | 1 |

| Alex Ramirez | R | 23 | RF | 441 | 406 | 46 | 81 | 14 | 1 | 4 | 33 | 32 | 117 | 19 | 6 |

| Corey Collins | L | 24 | DH | 271 | 230 | 19 | 33 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 29 | 92 | 2 | 1 |

| Vincent Perozo | L | 23 | C | 313 | 283 | 29 | 53 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 29 | 19 | 98 | 2 | 2 |

| Colin Houck | R | 21 | 3B | 502 | 460 | 55 | 84 | 17 | 4 | 8 | 44 | 33 | 204 | 6 | 3 |

| Jefrey De Los Santos | L | 23 | RF | 308 | 281 | 26 | 52 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 26 | 20 | 104 | 4 | 2 |

| Nick Roselli | L | 23 | 2B | 344 | 312 | 33 | 56 | 13 | 1 | 7 | 34 | 21 | 117 | 2 | 1 |

| Player | PA | BA | OBP | SLG | OPS+ | ISO | BABIP | Def | WAR | wOBA | 3YOPS+ | RC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juan Soto | 670 | .271 | .408 | .524 | 163 | .253 | .283 | -7 | 5.6 | .398 | 162 | 121 |

| Francisco Lindor | 672 | .263 | .338 | .453 | 123 | .190 | .290 | 6 | 5.4 | .342 | 116 | 98 |

| Bo Bichette | 598 | .294 | .339 | .445 | 121 | .151 | .331 | 5 | 3.8 | .339 | 118 | 87 |

| Marcus Semien | 581 | .244 | .315 | .390 | 100 | .146 | .268 | 8 | 2.8 | .309 | 93 | 67 |

| Brett Baty | 471 | .251 | .318 | .427 | 110 | .176 | .301 | 2 | 2.3 | .324 | 111 | 59 |

| Francisco Alvarez | 441 | .235 | .315 | .439 | 112 | .204 | .281 | -2 | 2.3 | .326 | 114 | 54 |

| Jorge Polanco | 473 | .253 | .327 | .446 | 118 | .193 | .279 | 6 | 2.1 | .334 | 112 | 63 |

| Luis Robert Jr. | 470 | .238 | .302 | .409 | 100 | .171 | .297 | 4 | 2.1 | .307 | 101 | 60 |

| Mark Vientos | 527 | .252 | .311 | .444 | 112 | .192 | .308 | -3 | 2.0 | .326 | 114 | 66 |

| Jacob Reimer | 518 | .234 | .313 | .403 | 102 | .169 | .288 | 1 | 1.9 | .312 | 105 | 60 |

| Ronny Mauricio | 460 | .242 | .291 | .394 | 93 | .152 | .300 | 8 | 1.8 | .296 | 95 | 53 |

| Jose Siri | 358 | .202 | .261 | .379 | 79 | .177 | .286 | 9 | 1.3 | .277 | 76 | 36 |

| Carson Benge | 522 | .246 | .326 | .399 | 105 | .153 | .296 | -9 | 1.2 | .317 | 109 | 64 |

| Luis Torrens | 271 | .249 | .300 | .378 | 92 | .129 | .306 | 4 | 1.2 | .296 | 91 | 29 |

| Ji Hwan Bae | 399 | .254 | .324 | .358 | 94 | .104 | .333 | -1 | 1.1 | .301 | 95 | 48 |

| Chris Suero | 487 | .204 | .304 | .334 | 82 | .130 | .282 | -3 | 1.0 | .287 | 89 | 48 |

| Jared Young | 407 | .242 | .325 | .423 | 111 | .181 | .290 | -3 | 0.9 | .327 | 106 | 51 |

| Ryan Clifford | 587 | .213 | .308 | .407 | 102 | .194 | .269 | 0 | 0.9 | .312 | 109 | 66 |

| Jackson Cluff | 365 | .204 | .289 | .332 | 77 | .129 | .295 | 2 | 0.8 | .277 | 75 | 34 |

| David Villar | 401 | .220 | .304 | .373 | 92 | .153 | .286 | 7 | 0.8 | .299 | 90 | 41 |

| Jesse Winker | 364 | .235 | .347 | .371 | 105 | .136 | .285 | 0 | 0.8 | .321 | 103 | 41 |

| Tyrone Taylor | 339 | .231 | .282 | .369 | 84 | .138 | .284 | 3 | 0.8 | .283 | 82 | 35 |

| Wyatt Young | 439 | .231 | .310 | .288 | 72 | .057 | .303 | 7 | 0.8 | .273 | 72 | 37 |

| Yonny Hernández | 400 | .241 | .316 | .297 | 76 | .056 | .286 | 5 | 0.7 | .278 | 76 | 37 |

| A.J. Ewing | 592 | .251 | .314 | .346 | 88 | .095 | .323 | -7 | 0.7 | .291 | 89 | 69 |

| Chris Williams | 321 | .194 | .280 | .350 | 78 | .156 | .282 | -1 | 0.5 | .279 | 75 | 28 |

| Kevin Parada | 440 | .218 | .280 | .358 | 81 | .140 | .304 | -4 | 0.5 | .280 | 85 | 41 |

| Jose Rojas | 434 | .219 | .293 | .419 | 100 | .201 | .253 | 0 | 0.5 | .307 | 94 | 49 |

| Gilberto Celestino | 385 | .236 | .312 | .311 | 79 | .075 | .308 | 6 | 0.4 | .282 | 79 | 36 |

| Starling Marte | 321 | .260 | .319 | .380 | 98 | .120 | .319 | 0 | 0.4 | .308 | 93 | 38 |

| Christian Arroyo | 236 | .247 | .292 | .365 | 86 | .119 | .304 | 5 | 0.4 | .288 | 82 | 24 |

| Luis De Los Santos | 365 | .217 | .269 | .320 | 67 | .103 | .291 | 6 | 0.3 | .261 | 67 | 30 |

| Rafael Ortega | 326 | .211 | .295 | .323 | 76 | .112 | .265 | 7 | 0.3 | .277 | 71 | 31 |

| Nick Morabito | 499 | .240 | .305 | .315 | 77 | .075 | .321 | -3 | 0.2 | .278 | 81 | 53 |

| Tsung-Che Cheng | 482 | .213 | .283 | .307 | 68 | .094 | .288 | 1 | 0.2 | .264 | 70 | 43 |

| Cristian Pache | 286 | .210 | .282 | .300 | 66 | .089 | .309 | 8 | 0.1 | .262 | 67 | 23 |

| Niko Goodrum | 247 | .218 | .328 | .322 | 87 | .104 | .316 | -6 | 0.1 | .296 | 81 | 25 |

| Jose Ramos | 467 | .214 | .276 | .362 | 80 | .148 | .323 | 6 | 0.1 | .280 | 85 | 45 |

| D’Andre Smith | 369 | .244 | .293 | .352 | 83 | .108 | .308 | 1 | 0.0 | .284 | 86 | 39 |

| Hayden Senger | 268 | .205 | .260 | .295 | 58 | .090 | .291 | 3 | 0.0 | .248 | 58 | 19 |

| Travis Swaggerty | 215 | .197 | .274 | .285 | 60 | .088 | .295 | 3 | -0.3 | .253 | 61 | 17 |

| JT Schwartz | 385 | .223 | .297 | .319 | 76 | .096 | .274 | 3 | -0.4 | .276 | 80 | 34 |

| Travis Jankowski | 193 | .218 | .302 | .265 | 64 | .047 | .277 | -3 | -0.4 | .262 | 62 | 16 |

| Estarling Mercado | 207 | .194 | .271 | .333 | 71 | .139 | .261 | 0 | -0.5 | .268 | 75 | 18 |

| Nick Lorusso | 436 | .213 | .268 | .316 | 66 | .103 | .290 | 0 | -0.5 | .258 | 69 | 36 |

| Marco Vargas | 448 | .205 | .277 | .252 | 53 | .047 | .271 | 3 | -0.5 | .243 | 57 | 34 |

| Eli Serrano III | 380 | .199 | .274 | .323 | 69 | .124 | .249 | -4 | -0.6 | .265 | 76 | 32 |

| Onix Vega | 203 | .202 | .271 | .257 | 52 | .055 | .263 | -3 | -0.6 | .241 | 59 | 14 |

| Troy Schreffler Jr. | 218 | .196 | .253 | .302 | 58 | .106 | .299 | 2 | -0.6 | .246 | 61 | 17 |

| Omar De Los Santos | 324 | .198 | .242 | .333 | 62 | .135 | .321 | 0 | -0.9 | .251 | 66 | 32 |

| Trace Willhoite | 428 | .186 | .266 | .336 | 70 | .150 | .247 | 1 | -0.9 | .266 | 75 | 36 |

| Yohairo Cuevas | 424 | .197 | .283 | .269 | 59 | .072 | .285 | 2 | -1.1 | .252 | 61 | 32 |

| William Lugo | 438 | .196 | .263 | .296 | 59 | .100 | .267 | -7 | -1.1 | .250 | 63 | 32 |

| Yonatan Henriquez | 423 | .200 | .268 | .296 | 61 | .096 | .254 | -6 | -1.2 | .253 | 67 | 36 |

| Ronald Hernandez | 422 | .197 | .263 | .278 | 55 | .081 | .267 | -8 | -1.2 | .244 | 61 | 31 |

| Diego Mosquera | 253 | .201 | .268 | .231 | 44 | .030 | .266 | 1 | -1.2 | .231 | 45 | 16 |

| Boston Baro | 451 | .210 | .255 | .295 | 56 | .086 | .269 | -8 | -1.4 | .242 | 61 | 35 |

| Alex Ramirez | 441 | .200 | .261 | .268 | 52 | .068 | .270 | 4 | -1.4 | .239 | 56 | 35 |

| Corey Collins | 271 | .143 | .262 | .235 | 43 | .092 | .211 | 0 | -1.4 | .235 | 46 | 15 |

| Vincent Perozo | 313 | .187 | .259 | .265 | 50 | .078 | .275 | -10 | -1.5 | .238 | 56 | 21 |

| Colin Houck | 502 | .183 | .243 | .289 | 51 | .106 | .306 | -2 | -1.7 | .237 | 60 | 35 |

| Jefrey De Los Santos | 308 | .185 | .245 | .285 | 51 | .100 | .277 | -3 | -1.8 | .235 | 57 | 21 |

| Nick Roselli | 344 | .179 | .245 | .295 | 53 | .116 | .261 | -13 | -2.1 | .241 | 59 | 23 |

| Player | Hit Comp 1 | Hit Comp 2 | Hit Comp 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Juan Soto | Rusty Staub | Carl Yastrzemski | Barry Bonds |

| Francisco Lindor | Marcus Semien | Charlie Gehringer | Carlos Guillén |

| Bo Bichette | Carney Lansford | Cecil Travis | Martín Prado |

| Marcus Semien | Eddie Mayo | Jimmy Rollins | Ian Kinsler |

| Brett Baty | Ryan Rua | Doug DeCinces | Ken Macha |

| Francisco Alvarez | Earl Williams | Todd Zeile | Derek Parks |

| Jorge Polanco | Greg Brock | Richie Hebner | Joe Collins |

| Luis Robert Jr. | Carl Everett | Bill Barrett | Jake Marisnick |

| Mark Vientos | Kevin Mitchell | Jeff Kent | Tony Perez |

| Jacob Reimer | Carlos Asuaje | Scott Romano | Bill Melton |

| Ronny Mauricio | Gene Freese | Tom Brookens | J.P. Roberge |

| Jose Siri | Billy Cowan | Corey Brown | Hiram Bocachica |

| Carson Benge | George Vukovich | Andrew McCutchen | Bernie Williams |

| Luis Torrens | Robert Machado | Tony Tornay | Shawn McGill |

| Ji Hwan Bae | Dave Collins | Mallex Smith | Joe Christopher |

| Chris Suero | Kurt Kingsolver | Jayson Werth | Ben Petrick |

| Jared Young | Armando Rios | Mike Yastrzemski | Jeffrey Hammonds |

| Ryan Clifford | Jon Singleton | Randy Schwartz | Cody Bellinger |

| Jackson Cluff | Anthony Granato | Joe Koppe | Jimmy Sexton |

| David Villar | Brad Nelson | Matt Skole | Mike Reddish |

| Jesse Winker | Norm Siebern | Lee Mazzilli | Steve Braun |

| Tyrone Taylor | Fehlandt Lentini | Jonny Kaplan | Joe Simpson |

| Wyatt Young | Derek Mann | Elio Chacon | Nick Shaw |

| Yonny Hernández | John Finn | Justin Henry | Christian Stringer |

| A.J. Ewing | Tyson Gillies | Lonnie Smith | Mallex Smith |

| Chris Williams | Jerry Goff | Arlo Brunsberg | Jayhawk Owens |

| Kevin Parada | Alfredo Torres | Bob Schmidt | Jack Fimple |

| Jose Rojas | Franklin Stubbs | Leon Durham | Chris Young |

| Gilberto Celestino | Trey Beamon | Neil Martin | L.J. Hoes |

| Starling Marte | Skeeter Barnes | George Metkovich | Bert Haas |

| Christian Arroyo | Ray Hamrick | Jay Ragni | Mark DeRosa |

| Luis De Los Santos | Dick Canan | Jim Gruber | Julio Cordido |

| Rafael Ortega | Cliff Heathcote | Sam Fuld | Willie Harris |

| Nick Morabito | Don White | Alejandro De Aza | Leo Sutherland |

| Tsung-Che Cheng | Hak-Ju Lee | Matt Smith | Juan Gonzalez |

| Cristian Pache | Mike Sullivan | Victor LaRose | Mark Doran |

| Niko Goodrum | Oscar Grimes | Anthony Seratelli | Drew Maggi |

| Jose Ramos | Marvin Stendel | Joe Gaetti | Bob Prentice |

| D’Andre Smith | D’Arby Myers | Hal Jeffcoat | Willie Romero |

| Hayden Senger | Otis Thornton | Tony DeFrancesco | Scott Knazek |

| Travis Swaggerty | Don Frailey | Zach Collier | Mark Thomas |

| JT Schwartz | Kevin Burford | Andy Barkett | Austin Davidson |

| Travis Jankowski | Jarrod Dyson | Jim Busby | Tack Wilson |

| Estarling Mercado | Daniel Berg | Jacob Julius | Ed Hartman |

| Nick Lorusso | Robert Mills | Sean Walsh | Bob Gergen |

| Marco Vargas | Elvis Pena | Larry Eckenrode | Forrest Wall |

| Eli Serrano III | Roger McSwain | Bob Wolenski | Jabari Henry |

| Onix Vega | Kevin Davidson | Jeremy Dowdy | Brent Mayne |

| Troy Schreffler Jr. | Kent Gerst | Brian Gump | Cristian Paulino |

| Omar De Los Santos | Dennis Hood | Tim Battle | Dorian Speed |

| Trace Willhoite | Garrick Haltiwanger | Curtis Suchan | Jim O’Rourke |

| Yohairo Cuevas | Adam Bonner | Michael Strickland | James Broughton |

| William Lugo | Ryan Stegall | Brett Elam | Jake Wald |

| Yonatan Henriquez | George Wright | Roberto Kelly | Jerry Bartee |

| Ronald Hernandez | Harry Billie | John Antonelli | Jim Lawrence |

| Diego Mosquera | Jerald Cain | Mark Miller | Earl Agnoly |

| Boston Baro | Ivan Castillo | Nick Allen | Gavin Lux |

| Alex Ramirez | Jay Johnson | Brandon Bridgers | Ossie Garcia |

| Corey Collins | Bill Brown | Samuel Antcliffe | De Jon Watson |

| Vincent Perozo | Parker Morin | Dallas Jones | Ray Bond |

| Colin Houck | Ron Dunn | Alex Liddi | Tony Taylor |

| Jefrey De Los Santos | Randy Black | Peter Fatse | Tim Curley |

| Nick Roselli | Chris Brown | Scott Clemo | Ryan Schimpf |

| Player | 80th BA | 80th OBP | 80th SLG | 80th OPS+ | 80th WAR | 20th BA | 20th OBP | 20th SLG | 20th OPS+ | 20th WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juan Soto | .296 | .436 | .594 | 187 | 7.3 | .248 | .382 | .473 | 145 | 4.1 |

| Francisco Lindor | .286 | .361 | .507 | 143 | 7.0 | .240 | .314 | .409 | 102 | 3.8 |

| Bo Bichette | .319 | .366 | .499 | 142 | 5.2 | .263 | .310 | .405 | 101 | 2.3 |

| Marcus Semien | .268 | .338 | .432 | 117 | 4.0 | .219 | .286 | .343 | 79 | 1.3 |

| Brett Baty | .276 | .348 | .482 | 131 | 3.6 | .222 | .294 | .371 | 89 | 1.1 |

| Francisco Alvarez | .263 | .343 | .502 | 137 | 3.6 | .208 | .285 | .382 | 91 | 1.3 |

| Jorge Polanco | .280 | .354 | .494 | 138 | 3.2 | .225 | .300 | .399 | 99 | 1.0 |

| Luis Robert Jr. | .264 | .326 | .464 | 122 | 3.4 | .212 | .277 | .364 | 82 | 1.0 |

| Mark Vientos | .277 | .338 | .503 | 134 | 3.4 | .225 | .281 | .387 | 90 | 0.6 |

| Jacob Reimer | .263 | .337 | .458 | 124 | 3.2 | .212 | .288 | .355 | 84 | 0.8 |

| Ronny Mauricio | .267 | .319 | .446 | 114 | 3.1 | .216 | .265 | .350 | 75 | 0.8 |

| Jose Siri | .229 | .293 | .437 | 104 | 2.4 | .176 | .234 | .319 | 59 | 0.3 |

| Carson Benge | .273 | .351 | .456 | 127 | 2.6 | .219 | .300 | .344 | 85 | 0.0 |

| Luis Torrens | .282 | .336 | .434 | 115 | 2.0 | .221 | .276 | .333 | 74 | 0.6 |

| Ji Hwan Bae | .281 | .348 | .404 | 112 | 2.0 | .225 | .293 | .317 | 76 | 0.2 |

| Chris Suero | .236 | .328 | .392 | 103 | 2.2 | .176 | .275 | .284 | 62 | -0.2 |

| Jared Young | .267 | .349 | .473 | 131 | 1.8 | .216 | .299 | .370 | 92 | 0.0 |

| Ryan Clifford | .241 | .339 | .464 | 123 | 2.3 | .186 | .281 | .355 | 79 | -0.7 |

| Jackson Cluff | .232 | .320 | .389 | 100 | 1.8 | .176 | .261 | .291 | 58 | 0.0 |

| David Villar | .245 | .331 | .425 | 112 | 1.9 | .192 | .274 | .324 | 71 | -0.2 |

| Jesse Winker | .265 | .376 | .420 | 126 | 1.7 | .206 | .316 | .315 | 81 | -0.2 |

| Tyrone Taylor | .259 | .313 | .426 | 108 | 1.8 | .202 | .253 | .322 | 65 | 0.0 |

| Wyatt Young | .261 | .339 | .316 | 87 | 1.7 | .205 | .284 | .249 | 55 | -0.1 |

| Yonny Hernández | .269 | .341 | .332 | 93 | 1.5 | .216 | .289 | .265 | 60 | -0.1 |

| A.J. Ewing | .280 | .342 | .389 | 108 | 2.1 | .221 | .289 | .303 | 70 | -0.7 |

| Chris Williams | .225 | .308 | .412 | 100 | 1.4 | .170 | .253 | .299 | 58 | -0.3 |

| Kevin Parada | .244 | .304 | .406 | 98 | 1.4 | .190 | .251 | .313 | 59 | -0.7 |

| Jose Rojas | .242 | .315 | .476 | 120 | 1.5 | .196 | .269 | .375 | 83 | -0.5 |

| Gilberto Celestino | .262 | .341 | .354 | 97 | 1.2 | .208 | .282 | .272 | 60 | -0.5 |

| Starling Marte | .289 | .348 | .424 | 118 | 1.3 | .229 | .291 | .339 | 80 | -0.3 |

| Christian Arroyo | .277 | .326 | .416 | 107 | 1.0 | .218 | .266 | .320 | 65 | -0.2 |

| Luis De Los Santos | .243 | .299 | .368 | 89 | 1.2 | .191 | .242 | .280 | 49 | -0.5 |

| Rafael Ortega | .240 | .325 | .380 | 97 | 1.2 | .181 | .266 | .275 | 55 | -0.5 |

| Nick Morabito | .264 | .328 | .352 | 92 | 1.1 | .214 | .282 | .283 | 63 | -0.7 |

| Tsung-Che Cheng | .239 | .309 | .346 | 87 | 1.2 | .187 | .261 | .270 | 54 | -0.8 |

| Cristian Pache | .242 | .307 | .341 | 84 | 0.8 | .181 | .250 | .260 | 47 | -0.5 |

| Niko Goodrum | .250 | .355 | .372 | 109 | 0.7 | .190 | .294 | .271 | 68 | -0.5 |

| Jose Ramos | .240 | .303 | .410 | 99 | 1.1 | .186 | .249 | .308 | 59 | -1.2 |

| D’Andre Smith | .266 | .316 | .395 | 98 | 0.7 | .218 | .267 | .314 | 66 | -0.7 |

| Hayden Senger | .239 | .293 | .347 | 83 | 0.9 | .176 | .231 | .255 | 40 | -0.6 |

| Travis Swaggerty | .225 | .307 | .330 | 80 | 0.2 | .172 | .249 | .246 | 43 | -0.8 |

| JT Schwartz | .254 | .324 | .371 | 96 | 0.5 | .200 | .273 | .283 | 60 | -1.2 |

| Travis Jankowski | .253 | .332 | .302 | 83 | 0.1 | .190 | .275 | .228 | 49 | -0.7 |

| Estarling Mercado | .223 | .300 | .386 | 90 | 0.0 | .170 | .245 | .286 | 52 | -1.0 |

| Nick Lorusso | .240 | .292 | .351 | 81 | 0.4 | .192 | .242 | .284 | 49 | -1.4 |

| Marco Vargas | .236 | .305 | .290 | 71 | 0.5 | .179 | .252 | .221 | 39 | -1.3 |

| Eli Serrano III | .224 | .296 | .370 | 86 | 0.2 | .175 | .247 | .279 | 50 | -1.5 |

| Onix Vega | .234 | .304 | .299 | 73 | 0.0 | .170 | .241 | .220 | 32 | -1.1 |

| Troy Schreffler Jr. | .227 | .282 | .352 | 80 | 0.0 | .171 | .229 | .261 | 42 | -1.0 |

| Omar De Los Santos | .227 | .267 | .391 | 84 | 0.0 | .173 | .215 | .288 | 44 | -1.7 |

| Trace Willhoite | .211 | .292 | .393 | 89 | 0.1 | .159 | .240 | .291 | 50 | -2.0 |

| Yohairo Cuevas | .226 | .312 | .308 | 77 | -0.1 | .175 | .258 | .233 | 43 | -1.9 |

| William Lugo | .224 | .290 | .341 | 77 | -0.1 | .171 | .234 | .258 | 41 | -2.1 |

| Yonatan Henriquez | .226 | .298 | .339 | 78 | -0.2 | .172 | .242 | .258 | 42 | -2.1 |

| Ronald Hernandez | .230 | .293 | .326 | 76 | 0.0 | .165 | .232 | .239 | 38 | -2.1 |

| Diego Mosquera | .232 | .296 | .266 | 61 | -0.8 | .175 | .239 | .198 | 27 | -1.8 |

| Boston Baro | .239 | .285 | .351 | 79 | -0.1 | .188 | .232 | .263 | 40 | -2.4 |

| Alex Ramirez | .227 | .286 | .301 | 68 | -0.5 | .178 | .236 | .235 | 37 | -2.2 |

| Corey Collins | .169 | .289 | .278 | 60 | -0.8 | .123 | .240 | .198 | 28 | -1.9 |

| Vincent Perozo | .222 | .295 | .315 | 73 | -0.7 | .160 | .235 | .229 | 35 | -2.1 |

| Colin Houck | .212 | .271 | .330 | 70 | -0.6 | .155 | .215 | .246 | 32 | -2.9 |

| Jefrey De Los Santos | .209 | .272 | .325 | 68 | -1.1 | .161 | .220 | .241 | 33 | -2.4 |

| Nick Roselli | .209 | .269 | .350 | 75 | -1.2 | .157 | .219 | .257 | 36 | -2.8 |

| Player | BA vs. L | OBP vs. L | SLG vs. L | BA vs. R | OBP vs. R | SLG vs. R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juan Soto | .260 | .383 | .468 | .277 | .420 | .551 |

| Francisco Lindor | .268 | .337 | .448 | .262 | .338 | .455 |

| Bo Bichette | .297 | .351 | .464 | .293 | .336 | .439 |

| Marcus Semien | .250 | .325 | .405 | .241 | .311 | .383 |

| Brett Baty | .240 | .303 | .395 | .256 | .325 | .441 |

| Francisco Alvarez | .239 | .331 | .451 | .232 | .306 | .432 |

| Jorge Polanco | .258 | .314 | .445 | .251 | .332 | .447 |

| Luis Robert Jr. | .254 | .323 | .430 | .232 | .294 | .401 |

| Mark Vientos | .266 | .323 | .468 | .244 | .305 | .430 |

| Jacob Reimer | .241 | .320 | .406 | .232 | .310 | .402 |

| Ronny Mauricio | .241 | .286 | .399 | .244 | .295 | .391 |

| Jose Siri | .206 | .271 | .393 | .200 | .255 | .373 |

| Carson Benge | .232 | .317 | .360 | .251 | .329 | .413 |

| Luis Torrens | .253 | .303 | .407 | .247 | .298 | .361 |

| Ji Hwan Bae | .246 | .308 | .331 | .258 | .332 | .371 |

| Chris Suero | .202 | .304 | .336 | .205 | .304 | .333 |

| Jared Young | .231 | .311 | .398 | .247 | .331 | .434 |

| Ryan Clifford | .203 | .293 | .366 | .216 | .313 | .420 |

| Jackson Cluff | .193 | .273 | .295 | .208 | .295 | .346 |

| David Villar | .226 | .316 | .383 | .217 | .297 | .367 |

| Jesse Winker | .219 | .337 | .342 | .239 | .350 | .380 |

| Tyrone Taylor | .233 | .286 | .369 | .230 | .280 | .368 |

| Wyatt Young | .226 | .303 | .283 | .232 | .313 | .289 |

| Yonny Hernández | .245 | .320 | .318 | .239 | .314 | .288 |

| A.J. Ewing | .247 | .306 | .329 | .253 | .317 | .353 |

| Chris Williams | .204 | .297 | .359 | .189 | .271 | .344 |

| Kevin Parada | .223 | .290 | .375 | .216 | .276 | .352 |

| Jose Rojas | .214 | .285 | .368 | .221 | .296 | .441 |

| Gilberto Celestino | .239 | .323 | .301 | .235 | .306 | .316 |

| Starling Marte | .266 | .322 | .380 | .258 | .318 | .380 |

| Christian Arroyo | .247 | .291 | .384 | .247 | .293 | .356 |

| Luis De Los Santos | .224 | .278 | .345 | .213 | .265 | .308 |

| Rafael Ortega | .200 | .274 | .277 | .214 | .302 | .336 |

| Nick Morabito | .228 | .294 | .293 | .245 | .309 | .323 |

| Tsung-Che Cheng | .211 | .274 | .293 | .214 | .287 | .313 |

| Cristian Pache | .224 | .303 | .318 | .200 | .267 | .287 |

| Niko Goodrum | .233 | .333 | .317 | .212 | .326 | .325 |

| Jose Ramos | .218 | .282 | .394 | .212 | .273 | .346 |

| D’Andre Smith | .245 | .294 | .373 | .244 | .292 | .343 |

| Hayden Senger | .203 | .256 | .278 | .206 | .263 | .303 |

| Travis Swaggerty | .194 | .260 | .299 | .198 | .282 | .278 |

| JT Schwartz | .212 | .288 | .283 | .228 | .300 | .333 |

| Travis Jankowski | .195 | .283 | .220 | .225 | .308 | .279 |

| Estarling Mercado | .184 | .259 | .265 | .197 | .275 | .358 |

| Nick Lorusso | .211 | .272 | .325 | .214 | .267 | .312 |

| Marco Vargas | .202 | .267 | .239 | .207 | .280 | .258 |

| Eli Serrano III | .188 | .255 | .313 | .204 | .281 | .327 |

| Onix Vega | .206 | .271 | .238 | .200 | .271 | .267 |

| Troy Schreffler Jr. | .203 | .273 | .322 | .193 | .245 | .293 |

| Omar De Los Santos | .194 | .240 | .337 | .200 | .243 | .332 |

| Trace Willhoite | .188 | .273 | .350 | .186 | .264 | .330 |

| Yohairo Cuevas | .186 | .270 | .235 | .201 | .288 | .281 |

| William Lugo | .200 | .268 | .304 | .194 | .260 | .293 |

| Yonatan Henriquez | .198 | .261 | .292 | .201 | .270 | .297 |

| Ronald Hernandez | .200 | .258 | .255 | .196 | .265 | .287 |

| Diego Mosquera | .194 | .260 | .224 | .204 | .271 | .235 |

| Boston Baro | .198 | .244 | .279 | .214 | .259 | .301 |

| Alex Ramirez | .206 | .273 | .260 | .196 | .255 | .273 |

| Corey Collins | .138 | .260 | .200 | .145 | .263 | .248 |

| Vincent Perozo | .184 | .259 | .263 | .188 | .259 | .266 |

| Colin Houck | .189 | .255 | .311 | .180 | .238 | .280 |

| Jefrey De Los Santos | .187 | .244 | .280 | .184 | .246 | .286 |

| Nick Roselli | .165 | .228 | .271 | .185 | .251 | .304 |

| Player | T | Age | W | L | ERA | G | GS | IP | H | ER | HR | BB | SO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freddy Peralta | R | 30 | 12 | 9 | 3.87 | 30 | 30 | 160.7 | 133 | 69 | 21 | 61 | 174 |

| Clay Holmes | R | 33 | 10 | 8 | 3.90 | 28 | 24 | 136.0 | 137 | 59 | 11 | 47 | 109 |

| Nolan McLean | R | 24 | 10 | 8 | 3.94 | 28 | 26 | 144.0 | 128 | 63 | 15 | 56 | 142 |

| Kodai Senga | R | 33 | 8 | 7 | 3.82 | 25 | 25 | 127.3 | 110 | 54 | 15 | 58 | 125 |

| David Peterson | L | 30 | 7 | 7 | 4.07 | 28 | 27 | 146.0 | 140 | 66 | 13 | 58 | 133 |

| Jonah Tong | R | 23 | 9 | 8 | 4.07 | 26 | 25 | 117.3 | 103 | 53 | 15 | 48 | 132 |

| Tylor Megill | R | 30 | 6 | 6 | 4.00 | 21 | 21 | 96.0 | 87 | 45 | 11 | 41 | 105 |

| Devin Williams | R | 31 | 6 | 4 | 3.14 | 61 | 0 | 57.3 | 39 | 20 | 5 | 23 | 79 |

| Tobias Myers | R | 27 | 6 | 6 | 4.38 | 29 | 20 | 111.0 | 113 | 54 | 15 | 36 | 89 |

| Jonathan Pintaro | R | 28 | 4 | 3 | 4.10 | 26 | 15 | 74.7 | 70 | 34 | 8 | 30 | 71 |

| Jonathan Santucci | L | 23 | 6 | 6 | 4.70 | 24 | 22 | 105.3 | 103 | 55 | 15 | 39 | 91 |

| Jack Wenninger | R | 24 | 7 | 8 | 4.71 | 24 | 22 | 116.7 | 118 | 61 | 17 | 40 | 95 |

| Sean Manaea | L | 34 | 5 | 5 | 4.51 | 22 | 18 | 101.7 | 94 | 51 | 16 | 31 | 104 |

| Joander Suarez | R | 26 | 5 | 7 | 4.57 | 21 | 17 | 90.7 | 94 | 46 | 13 | 25 | 72 |

| Justin Hagenman | R | 29 | 3 | 4 | 4.46 | 30 | 12 | 84.7 | 85 | 42 | 13 | 20 | 74 |

| R.J. Gordon | R | 24 | 6 | 7 | 4.84 | 24 | 19 | 113.3 | 113 | 61 | 17 | 41 | 95 |

| Griffin Canning | R | 30 | 6 | 6 | 4.76 | 20 | 20 | 102.0 | 100 | 54 | 17 | 40 | 92 |

| A.J. Minter | L | 32 | 5 | 3 | 3.53 | 56 | 0 | 51.0 | 43 | 20 | 6 | 17 | 56 |

| Cooper Criswell | R | 29 | 4 | 5 | 4.67 | 24 | 16 | 90.7 | 92 | 47 | 12 | 29 | 71 |

| Brandon Waddell | L | 32 | 5 | 5 | 4.67 | 24 | 14 | 86.7 | 89 | 45 | 12 | 29 | 68 |

| Christian Scott | R | 27 | 3 | 3 | 4.55 | 14 | 14 | 63.3 | 62 | 32 | 9 | 18 | 55 |

| Luke Weaver | R | 32 | 4 | 4 | 4.30 | 47 | 5 | 69.0 | 64 | 33 | 10 | 24 | 76 |

| Zach Thornton | L | 24 | 4 | 5 | 4.65 | 16 | 15 | 69.7 | 71 | 36 | 9 | 22 | 53 |

| Felipe De La Cruz | L | 25 | 4 | 5 | 4.66 | 27 | 12 | 75.3 | 75 | 39 | 10 | 34 | 70 |

| Will Watson | R | 23 | 5 | 6 | 4.98 | 26 | 21 | 103.0 | 100 | 57 | 14 | 49 | 90 |

| Robert Stock | R | 36 | 3 | 5 | 4.86 | 18 | 13 | 70.3 | 70 | 38 | 10 | 31 | 64 |

| Brooks Raley | L | 38 | 2 | 2 | 3.79 | 41 | 1 | 35.7 | 30 | 15 | 3 | 12 | 35 |

| Carl Edwards Jr. | R | 34 | 2 | 3 | 4.44 | 25 | 6 | 52.7 | 52 | 26 | 7 | 23 | 45 |

| Kevin Herget | R | 35 | 2 | 2 | 4.28 | 35 | 4 | 54.7 | 56 | 26 | 7 | 15 | 44 |

| Joey Gerber | R | 29 | 1 | 1 | 4.43 | 32 | 8 | 42.7 | 41 | 21 | 6 | 14 | 40 |

| Huascar Brazobán | R | 36 | 3 | 3 | 4.26 | 50 | 2 | 61.3 | 56 | 29 | 6 | 29 | 58 |

| Luis García | R | 39 | 2 | 2 | 4.10 | 51 | 1 | 48.3 | 48 | 22 | 4 | 20 | 43 |

| Dylan Ross | R | 25 | 1 | 1 | 4.12 | 53 | 0 | 54.7 | 47 | 25 | 7 | 26 | 58 |

| Brendan Girton | R | 24 | 3 | 4 | 5.03 | 24 | 20 | 78.7 | 76 | 44 | 10 | 38 | 66 |

| Reed Garrett | R | 33 | 4 | 3 | 3.99 | 37 | 0 | 38.3 | 35 | 17 | 4 | 19 | 41 |

| Max Kranick | R | 28 | 2 | 1 | 4.46 | 26 | 4 | 40.3 | 41 | 20 | 6 | 11 | 31 |

| Richard Lovelady | L | 30 | 2 | 2 | 4.27 | 43 | 1 | 46.3 | 44 | 22 | 5 | 15 | 43 |

| Aaron Rozek | L | 30 | 3 | 4 | 5.05 | 26 | 11 | 92.7 | 100 | 52 | 14 | 30 | 66 |

| Adbert Alzolay | R | 31 | 2 | 3 | 4.25 | 31 | 1 | 36.0 | 34 | 17 | 5 | 11 | 32 |

| Luis Moreno | R | 27 | 5 | 7 | 5.08 | 31 | 12 | 85.0 | 88 | 48 | 11 | 40 | 64 |

| Jordan Geber | R | 26 | 3 | 3 | 4.97 | 20 | 8 | 54.3 | 59 | 30 | 8 | 20 | 35 |

| Dedniel Núñez | R | 30 | 2 | 2 | 4.17 | 28 | 0 | 36.7 | 34 | 17 | 5 | 15 | 38 |

| Austin Warren | R | 30 | 5 | 5 | 4.53 | 35 | 3 | 51.7 | 49 | 26 | 7 | 20 | 47 |

| Joe Jacques | L | 31 | 2 | 2 | 4.35 | 43 | 1 | 49.7 | 49 | 24 | 5 | 18 | 42 |

| Douglas Orellana | R | 24 | 2 | 3 | 4.82 | 32 | 6 | 52.3 | 50 | 28 | 8 | 28 | 51 |

| Colin Poche | L | 32 | 3 | 3 | 4.46 | 45 | 0 | 40.3 | 37 | 20 | 6 | 17 | 37 |

| Nate Lavender | L | 26 | 3 | 2 | 4.37 | 25 | 0 | 35.0 | 30 | 17 | 4 | 18 | 38 |

| José Castillo | L | 30 | 2 | 3 | 4.32 | 39 | 0 | 41.7 | 39 | 20 | 5 | 18 | 43 |

| Brian Metoyer | R | 29 | 1 | 1 | 4.50 | 33 | 0 | 36.0 | 31 | 18 | 4 | 19 | 40 |

| Ryan Lambert | R | 23 | 1 | 2 | 4.53 | 47 | 0 | 47.7 | 41 | 24 | 6 | 25 | 53 |

| Nick Burdi | R | 33 | 2 | 1 | 4.50 | 33 | 0 | 36.0 | 31 | 18 | 4 | 19 | 39 |

| Alex Carrillo | R | 29 | 3 | 4 | 4.57 | 37 | 0 | 43.3 | 39 | 22 | 6 | 20 | 45 |

| Saul Garcia | R | 23 | 3 | 5 | 5.12 | 31 | 4 | 51.0 | 47 | 29 | 7 | 29 | 51 |

| Frankie Montas | R | 33 | 4 | 7 | 5.44 | 18 | 17 | 86.0 | 90 | 52 | 14 | 38 | 71 |

| Carlos Guzman | R | 28 | 3 | 5 | 5.07 | 34 | 4 | 55.0 | 55 | 31 | 8 | 25 | 46 |

| Jefry Yan | L | 29 | 2 | 3 | 4.75 | 29 | 1 | 36.0 | 31 | 19 | 4 | 23 | 40 |

| Drew Smith | R | 32 | 2 | 3 | 4.79 | 37 | 0 | 35.7 | 34 | 19 | 6 | 17 | 36 |

| Matt Turner | L | 26 | 1 | 2 | 5.08 | 36 | 3 | 51.3 | 51 | 29 | 7 | 25 | 42 |

| Hunter Parsons | R | 29 | 2 | 3 | 4.98 | 24 | 0 | 34.3 | 32 | 19 | 5 | 17 | 34 |

| Joshua Cornielly | R | 25 | 3 | 4 | 4.97 | 34 | 1 | 50.7 | 50 | 28 | 8 | 20 | 44 |

| Robinson Martínez | R | 28 | 1 | 1 | 4.94 | 26 | 0 | 31.0 | 30 | 17 | 4 | 17 | 29 |

| Zach Peek | R | 28 | 5 | 6 | 4.85 | 35 | 1 | 55.7 | 56 | 30 | 8 | 26 | 48 |

| Trey McGough | L | 28 | 2 | 3 | 5.02 | 24 | 1 | 43.0 | 43 | 24 | 6 | 22 | 35 |

| Ben Simon | R | 24 | 2 | 4 | 4.96 | 33 | 0 | 45.3 | 46 | 25 | 6 | 17 | 35 |

| Daniel Juarez | L | 25 | 2 | 2 | 5.05 | 27 | 0 | 35.7 | 36 | 20 | 5 | 17 | 28 |

| Justin Garza | R | 32 | 2 | 4 | 5.40 | 38 | 1 | 43.3 | 46 | 26 | 7 | 17 | 34 |

| Player | IP | K/9 | BB/9 | HR/9 | BB% | K% | BABIP | ERA+ | 3ERA+ | FIP | ERA- | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freddy Peralta | 160.7 | 9.7 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 9.1% | 25.9% | .273 | 108 | 106 | 3.97 | 93 | 2.5 |

| Clay Holmes | 136.0 | 7.2 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 8.0% | 18.5% | .304 | 107 | 103 | 3.83 | 94 | 2.4 |

| Nolan McLean | 144.0 | 8.9 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 9.2% | 23.2% | .288 | 106 | 107 | 3.98 | 94 | 2.3 |

| Kodai Senga | 127.3 | 8.8 | 4.1 | 1.1 | 10.5% | 22.7% | .277 | 109 | 105 | 4.19 | 92 | 2.1 |

| David Peterson | 146.0 | 8.2 | 3.6 | 0.8 | 9.2% | 21.1% | .301 | 103 | 100 | 3.83 | 97 | 2.0 |

| Jonah Tong | 117.3 | 10.1 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 9.6% | 26.3% | .293 | 103 | 107 | 3.85 | 97 | 1.7 |

| Tylor Megill | 96.0 | 9.8 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 9.9% | 25.3% | .300 | 99 | 97 | 3.93 | 101 | 1.2 |

| Devin Williams | 57.3 | 12.4 | 3.6 | 0.8 | 9.8% | 33.8% | .274 | 133 | 126 | 2.90 | 75 | 1.1 |

| Tobias Myers | 111.0 | 7.2 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 7.5% | 18.6% | .293 | 95 | 97 | 4.40 | 105 | 1.0 |

| Jonathan Pintaro | 74.7 | 8.6 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 9.3% | 22.0% | .295 | 102 | 101 | 4.14 | 98 | 0.9 |

| Jonathan Santucci | 105.3 | 7.8 | 3.3 | 1.3 | 8.5% | 19.9% | .289 | 89 | 94 | 4.48 | 112 | 0.8 |

| Jack Wenninger | 116.7 | 7.3 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 7.8% | 18.6% | .291 | 89 | 94 | 4.59 | 112 | 0.8 |

| Sean Manaea | 101.7 | 9.2 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 7.3% | 24.5% | .287 | 92 | 86 | 4.26 | 109 | 0.8 |

| Joander Suarez | 90.7 | 7.1 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 6.4% | 18.6% | .296 | 91 | 95 | 4.40 | 110 | 0.8 |

| Justin Hagenman | 84.7 | 7.9 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 5.6% | 20.9% | .293 | 93 | 94 | 4.23 | 108 | 0.7 |

| R.J. Gordon | 113.3 | 7.5 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 8.4% | 19.3% | .288 | 86 | 91 | 4.60 | 116 | 0.6 |

| Griffin Canning | 102.0 | 8.1 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 9.0% | 20.8% | .286 | 88 | 87 | 4.79 | 114 | 0.6 |

| A.J. Minter | 51.0 | 9.9 | 3.0 | 1.1 | 8.0% | 26.4% | .282 | 118 | 112 | 3.56 | 85 | 0.6 |

| Cooper Criswell | 90.7 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 7.5% | 18.3% | .292 | 89 | 89 | 4.54 | 112 | 0.6 |

| Brandon Waddell | 86.7 | 7.1 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 7.8% | 18.2% | .294 | 89 | 86 | 4.67 | 112 | 0.5 |

| Christian Scott | 63.3 | 7.8 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 6.8% | 20.8% | .290 | 92 | 94 | 4.32 | 109 | 0.5 |

| Luke Weaver | 69.0 | 9.9 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 8.2% | 25.9% | .298 | 97 | 94 | 3.98 | 103 | 0.5 |

| Zach Thornton | 69.7 | 6.8 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 7.4% | 17.7% | .291 | 90 | 95 | 4.48 | 111 | 0.5 |

| Felipe De La Cruz | 75.3 | 8.4 | 4.1 | 1.2 | 10.1% | 20.8% | .301 | 90 | 93 | 4.54 | 112 | 0.4 |

| Will Watson | 103.0 | 7.9 | 4.3 | 1.2 | 10.7% | 19.7% | .289 | 84 | 90 | 4.76 | 119 | 0.4 |

| Robert Stock | 70.3 | 8.2 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 10.0% | 20.6% | .297 | 86 | 78 | 4.90 | 117 | 0.3 |

| Brooks Raley | 35.7 | 8.8 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 8.2% | 23.8% | .278 | 110 | 97 | 3.64 | 91 | 0.3 |

| Carl Edwards Jr. | 52.7 | 7.7 | 3.9 | 1.2 | 10.0% | 19.5% | .292 | 94 | 87 | 4.55 | 107 | 0.3 |

| Kevin Herget | 54.7 | 7.2 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 6.4% | 18.9% | .297 | 97 | 90 | 4.15 | 103 | 0.3 |

| Joey Gerber | 42.7 | 8.4 | 3.0 | 1.3 | 7.7% | 21.9% | .292 | 94 | 95 | 4.24 | 106 | 0.3 |

| Huascar Brazobán | 61.3 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 10.7% | 21.5% | .291 | 98 | 89 | 4.16 | 102 | 0.3 |

| Luis García | 48.3 | 8.0 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 9.3% | 20.0% | .308 | 102 | 98 | 3.89 | 98 | 0.3 |

| Dylan Ross | 54.7 | 9.5 | 4.3 | 1.2 | 10.9% | 24.4% | .282 | 101 | 108 | 4.19 | 99 | 0.2 |

| Brendan Girton | 78.7 | 7.5 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 10.9% | 19.0% | .287 | 83 | 87 | 4.85 | 120 | 0.2 |

| Reed Garrett | 38.3 | 9.6 | 4.5 | 0.9 | 11.2% | 24.3% | .304 | 105 | 97 | 3.95 | 95 | 0.2 |

| Max Kranick | 40.3 | 6.9 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 6.4% | 18.1% | .287 | 93 | 94 | 4.45 | 107 | 0.2 |

| Richard Lovelady | 46.3 | 8.4 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 7.7% | 21.9% | .295 | 98 | 98 | 4.01 | 102 | 0.2 |

| Aaron Rozek | 92.7 | 6.4 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 7.4% | 16.3% | .296 | 83 | 82 | 4.84 | 121 | 0.1 |

| Adbert Alzolay | 36.0 | 8.0 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 7.3% | 21.2% | .284 | 98 | 95 | 4.36 | 102 | 0.1 |

| Luis Moreno | 85.0 | 6.8 | 4.2 | 1.2 | 10.4% | 16.7% | .294 | 82 | 84 | 4.96 | 122 | 0.1 |

| Jordan Geber | 54.3 | 5.8 | 3.3 | 1.3 | 8.3% | 14.5% | .291 | 84 | 87 | 5.00 | 119 | 0.1 |

| Dedniel Núñez | 36.7 | 9.3 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 9.4% | 23.9% | .293 | 100 | 100 | 4.09 | 100 | 0.1 |

| Austin Warren | 51.7 | 8.2 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 9.0% | 21.2% | .288 | 92 | 92 | 4.50 | 109 | 0.1 |

| Joe Jacques | 49.7 | 7.6 | 3.3 | 0.9 | 8.4% | 19.5% | .299 | 96 | 92 | 4.23 | 104 | 0.1 |

| Douglas Orellana | 52.3 | 8.8 | 4.8 | 1.4 | 11.9% | 21.6% | .292 | 87 | 93 | 4.92 | 115 | 0.1 |

| Colin Poche | 40.3 | 8.3 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 9.8% | 21.3% | .277 | 93 | 92 | 4.53 | 107 | 0.0 |

| Nate Lavender | 35.0 | 9.8 | 4.6 | 1.0 | 11.8% | 24.8% | .286 | 95 | 98 | 4.28 | 105 | 0.0 |

| José Castillo | 41.7 | 9.3 | 3.9 | 1.1 | 10.0% | 23.9% | .301 | 97 | 93 | 4.24 | 103 | 0.0 |

| Brian Metoyer | 36.0 | 10.0 | 4.8 | 1.0 | 11.6% | 24.4% | .290 | 93 | 93 | 4.39 | 108 | 0.0 |

| Ryan Lambert | 47.7 | 10.0 | 4.7 | 1.1 | 11.8% | 25.1% | .287 | 92 | 100 | 4.34 | 109 | 0.0 |

| Nick Burdi | 36.0 | 9.8 | 4.8 | 1.0 | 11.8% | 24.2% | .287 | 93 | 88 | 4.36 | 108 | 0.0 |

| Alex Carrillo | 43.3 | 9.3 | 4.2 | 1.2 | 10.4% | 23.3% | .287 | 91 | 90 | 4.48 | 110 | -0.1 |

| Saul Garcia | 51.0 | 9.0 | 5.1 | 1.2 | 12.6% | 22.1% | .288 | 82 | 88 | 4.95 | 122 | -0.1 |

| Frankie Montas | 86.0 | 7.4 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 9.9% | 18.5% | .296 | 77 | 73 | 5.09 | 130 | -0.1 |

| Carlos Guzman | 55.0 | 7.5 | 4.1 | 1.3 | 10.2% | 18.8% | .290 | 82 | 84 | 4.96 | 122 | -0.1 |

| Jefry Yan | 36.0 | 10.0 | 5.8 | 1.0 | 13.7% | 23.8% | .290 | 88 | 86 | 4.64 | 114 | -0.1 |

| Drew Smith | 35.7 | 9.1 | 4.3 | 1.5 | 10.8% | 22.8% | .289 | 87 | 85 | 4.85 | 115 | -0.1 |

| Matt Turner | 51.3 | 7.4 | 4.4 | 1.2 | 10.9% | 18.3% | .289 | 82 | 86 | 5.05 | 122 | -0.2 |

| Hunter Parsons | 34.3 | 8.9 | 4.5 | 1.3 | 11.1% | 22.2% | .287 | 84 | 85 | 4.82 | 119 | -0.2 |

| Joshua Cornielly | 50.7 | 7.8 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 9.0% | 19.7% | .288 | 84 | 90 | 4.96 | 119 | -0.2 |

| Robinson Martínez | 31.0 | 8.4 | 4.9 | 1.2 | 12.1% | 20.7% | .295 | 85 | 84 | 4.91 | 118 | -0.2 |

| Zach Peek | 55.7 | 7.8 | 4.2 | 1.3 | 10.4% | 19.1% | .294 | 86 | 87 | 4.87 | 116 | -0.2 |

| Trey McGough | 43.0 | 7.3 | 4.6 | 1.3 | 11.4% | 18.1% | .289 | 83 | 84 | 4.88 | 120 | -0.2 |

| Ben Simon | 45.3 | 7.0 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 8.5% | 17.5% | .292 | 84 | 88 | 4.80 | 119 | -0.3 |

| Daniel Juarez | 35.7 | 7.1 | 4.3 | 1.3 | 10.7% | 17.6% | .290 | 83 | 87 | 5.10 | 120 | -0.3 |

| Justin Garza | 43.3 | 7.1 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 8.8% | 17.5% | .295 | 77 | 75 | 5.01 | 130 | -0.4 |

| Player | BA vs. L | OBP vs. L | SLG vs. L | BA vs. R | OBP vs. R | SLG vs. R | 80th WAR | 20th WAR | 80th ERA | 20th ERA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freddy Peralta | .216 | .306 | .353 | .227 | .292 | .406 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 3.32 | 4.50 |

| Clay Holmes | .262 | .339 | .403 | .248 | .306 | .355 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 3.47 | 4.46 |

| Nolan McLean | .243 | .335 | .393 | .221 | .294 | .349 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 3.51 | 4.64 |

| Kodai Senga | .233 | .330 | .377 | .226 | .301 | .379 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 3.33 | 4.42 |

| David Peterson | .226 | .288 | .329 | .252 | .331 | .388 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 3.44 | 4.82 |

| Jonah Tong | .214 | .292 | .405 | .241 | .313 | .363 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 3.43 | 4.80 |

| Tylor Megill | .243 | .340 | .403 | .226 | .297 | .363 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 3.63 | 4.99 |

| Devin Williams | .194 | .301 | .337 | .187 | .261 | .280 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 2.28 | 4.64 |

| Tobias Myers | .259 | .326 | .412 | .256 | .309 | .430 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 3.82 | 4.97 |

| Jonathan Pintaro | .268 | .354 | .391 | .214 | .295 | .364 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 3.57 | 4.72 |

| Jonathan Santucci | .255 | .331 | .391 | .247 | .310 | .428 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 4.14 | 5.34 |

| Jack Wenninger | .241 | .314 | .398 | .267 | .322 | .449 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 4.18 | 5.29 |

| Sean Manaea | .216 | .271 | .352 | .248 | .313 | .442 | 1.5 | -0.1 | 3.90 | 5.49 |

| Joander Suarez | .284 | .340 | .481 | .236 | .285 | .382 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 4.03 | 5.28 |

| Justin Hagenman | .255 | .307 | .451 | .256 | .295 | .422 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 3.79 | 5.24 |

| R.J. Gordon | .235 | .307 | .417 | .266 | .325 | .434 | 1.3 | -0.2 | 4.38 | 5.51 |

| Griffin Canning | .253 | .336 | .454 | .252 | .311 | .431 | 1.3 | -0.2 | 4.20 | 5.51 |

| A.J. Minter | .206 | .265 | .286 | .236 | .305 | .417 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 2.77 | 4.55 |

| Cooper Criswell | .266 | .342 | .456 | .249 | .308 | .392 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 4.13 | 5.35 |

| Brandon Waddell | .273 | .341 | .400 | .253 | .323 | .442 | 1.1 | -0.1 | 4.13 | 5.32 |

| Christian Scott | .246 | .301 | .434 | .256 | .319 | .408 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 3.88 | 5.19 |

| Luke Weaver | .240 | .313 | .403 | .237 | .296 | .410 | 1.3 | -0.2 | 3.42 | 5.34 |

| Zach Thornton | .232 | .297 | .305 | .267 | .330 | .462 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 4.09 | 5.27 |

| Felipe De La Cruz | .253 | .330 | .407 | .250 | .335 | .418 | 1.1 | -0.2 | 4.02 | 5.34 |

| Will Watson | .238 | .335 | .386 | .256 | .333 | .437 | 1.1 | -0.4 | 4.53 | 5.65 |

| Robert Stock | .271 | .362 | .450 | .236 | .329 | .392 | 0.8 | -0.2 | 4.24 | 5.68 |

| Brooks Raley | .195 | .267 | .293 | .244 | .330 | .389 | 0.7 | -0.2 | 2.85 | 5.07 |

| Carl Edwards Jr. | .264 | .340 | .396 | .243 | .318 | .435 | 0.7 | -0.1 | 3.85 | 5.29 |

| Kevin Herget | .253 | .308 | .421 | .264 | .313 | .413 | 0.7 | -0.2 | 3.59 | 5.30 |

| Joey Gerber | .244 | .319 | .402 | .244 | .298 | .419 | 0.7 | -0.1 | 3.66 | 5.37 |

| Huascar Brazobán | .248 | .344 | .381 | .231 | .318 | .362 | 0.9 | -0.5 | 3.46 | 5.41 |

| Luis García | .277 | .362 | .410 | .231 | .306 | .352 | 0.7 | -0.2 | 3.30 | 5.26 |

| Dylan Ross | .238 | .330 | .386 | .217 | .300 | .377 | 0.8 | -0.4 | 3.43 | 5.11 |

| Brendan Girton | .258 | .351 | .437 | .237 | .333 | .385 | 0.7 | -0.3 | 4.55 | 5.64 |

| Reed Garrett | .239 | .338 | .403 | .229 | .309 | .349 | 0.6 | -0.3 | 3.24 | 4.97 |

| Max Kranick | .273 | .325 | .468 | .241 | .289 | .398 | 0.5 | -0.2 | 3.87 | 5.30 |

| Richard Lovelady | .219 | .306 | .313 | .256 | .323 | .427 | 0.6 | -0.3 | 3.44 | 5.15 |

| Aaron Rozek | .239 | .302 | .359 | .281 | .340 | .488 | 0.7 | -0.6 | 4.52 | 5.80 |

| Adbert Alzolay | .273 | .342 | .470 | .222 | .288 | .375 | 0.5 | -0.3 | 3.55 | 5.25 |

| Luis Moreno | .275 | .364 | .438 | .249 | .332 | .411 | 0.7 | -0.5 | 4.55 | 5.75 |

| Jordan Geber | .262 | .333 | .458 | .274 | .331 | .425 | 0.4 | -0.3 | 4.45 | 5.51 |

| Dedniel Núñez | .262 | .342 | .446 | .224 | .286 | .382 | 0.5 | -0.2 | 3.32 | 5.17 |

| Austin Warren | .225 | .314 | .393 | .264 | .333 | .427 | 0.5 | -0.4 | 3.87 | 5.45 |

| Joe Jacques | .221 | .299 | .309 | .266 | .345 | .430 | 0.5 | -0.4 | 3.62 | 5.12 |

| Douglas Orellana | .253 | .342 | .414 | .236 | .333 | .425 | 0.5 | -0.4 | 4.17 | 5.57 |

| Colin Poche | .229 | .315 | .438 | .250 | .319 | .413 | 0.5 | -0.4 | 3.68 | 5.47 |

| Nate Lavender | .250 | .365 | .386 | .213 | .311 | .371 | 0.4 | -0.3 | 3.58 | 5.29 |

| José Castillo | .231 | .333 | .327 | .241 | .323 | .420 | 0.4 | -0.4 | 3.61 | 5.34 |

| Brian Metoyer | .222 | .347 | .397 | .233 | .337 | .356 | 0.4 | -0.4 | 3.69 | 5.42 |

| Ryan Lambert | .244 | .350 | .453 | .208 | .306 | .313 | 0.4 | -0.5 | 3.89 | 5.36 |

| Nick Burdi | .234 | .355 | .406 | .222 | .321 | .347 | 0.3 | -0.5 | 3.64 | 5.80 |

| Alex Carrillo | .250 | .348 | .475 | .218 | .303 | .333 | 0.3 | -0.6 | 3.85 | 5.73 |

| Saul Garcia | .240 | .354 | .417 | .233 | .339 | .388 | 0.3 | -0.6 | 4.46 | 5.96 |

| Frankie Montas | .279 | .365 | .497 | .246 | .315 | .408 | 0.4 | -0.7 | 4.89 | 6.12 |

| Carlos Guzman | .263 | .357 | .455 | .248 | .326 | .402 | 0.3 | -0.6 | 4.39 | 6.00 |

| Jefry Yan | .200 | .345 | .289 | .239 | .355 | .413 | 0.3 | -0.6 | 3.93 | 5.95 |

| Drew Smith | .250 | .348 | .450 | .244 | .318 | .436 | 0.2 | -0.6 | 4.03 | 6.01 |

| Matt Turner | .234 | .333 | .375 | .261 | .352 | .442 | 0.3 | -0.6 | 4.42 | 5.82 |

| Hunter Parsons | .263 | .373 | .439 | .227 | .314 | .413 | 0.1 | -0.6 | 4.28 | 5.99 |

| Joshua Cornielly | .260 | .345 | .458 | .243 | .319 | .408 | 0.2 | -0.5 | 4.26 | 5.55 |

| Robinson Martínez | .232 | .348 | .411 | .262 | .355 | .415 | 0.0 | -0.5 | 4.31 | 5.78 |

| Zach Peek | .240 | .333 | .423 | .267 | .344 | .431 | 0.3 | -0.8 | 4.19 | 5.70 |

| Trey McGough | .241 | .323 | .328 | .261 | .346 | .477 | 0.1 | -0.6 | 4.42 | 5.82 |

| Ben Simon | .256 | .337 | .427 | .253 | .330 | .414 | 0.0 | -0.7 | 4.42 | 5.62 |

| Daniel Juarez | .240 | .333 | .400 | .267 | .356 | .444 | 0.0 | -0.5 | 4.45 | 5.55 |

| Justin Garza | .270 | .357 | .473 | .260 | .318 | .440 | 0.0 | -0.8 | 4.70 | 6.42 |

Players are listed with their most recent teams wherever possible. This includes players who are unsigned or have retired, players who will miss 2026 due to injury, and players who were released in 2025. So yes, if you see Joe Schmoe, who quit baseball back in August to form a Ambient Math-Rock Trip-Hop Yacht Metal band that only performs in abandoned malls, he’s still listed here intentionally. ZiPS is assuming a league with an ERA of 4.16.

Hitters are ranked by zWAR, which is to say, WAR values as calculated by me, Dan Szymborski, whose surname is spelled with a z. WAR values might differ slightly from those that appear in the full release of ZiPS. Finally, I will advise anyone against — and might karate chop anyone guilty of — merely adding up WAR totals on a depth chart to produce projected team WAR. It is important to remember that ZiPS is agnostic about playing time, and has no information about, for example, how quickly a team will call up a prospect or what veteran has fallen into disfavor.

As always, incorrect projections are either caused by misinformation, a non-pragmatic reality, or by the skillful sabotage of our friend and former editor. You can, however, still get mad at me on Twitter or on Bluesky. This last is, however, not an actual requirement.

As Before, So Again: Cody Bellinger Is a Yankee

Our long national nightmare is over. After weeks of back and forth between Cody Bellinger and the New York Yankees, it’s official: He’s staying in the Bronx. The two sides have agreed to a five-year, $162.5 million deal with opt outs after the second and third seasons, a $20 million signing bonus, and a full no-trade clause, as first reported by Jeff Passan.

This fit was so obvious that it almost had to happen. The Yankees need offense, and they’d prefer it to come in the form of a left-handed outfielder who can cover center field in a pinch. They’re already familiar with Bellinger, who just put up a 5-WAR season in pinstripes. No other teams needed this exact type of player as much, at this current moment, as they did. Likewise, Bellinger was probably going to have to sign with the Yankees to get the deal he wanted. Now that that foregone conclusion has been reached, let’s unpack how this all fits together.

This contract is the culmination of a long, decorated career that was conspicuously lacking in free agency appeal. Bellinger burst onto the scene in 2017 with 39 homers for the Dodgers, taking Rookie of the Year honors in the process. He then went fully supersonic in the homer-happy 2019 season, with the rocket ball propelling him to 47 homers, a 161 wRC+, and NL MVP honors. Disaster struck in the 2020 World Series, however. Bellinger dislocated his shoulder celebrating a home run, and his performance fell off a cliff immediately after. Read the rest of this entry »

Mets Snag Luis Robert Jr. From White Sox

With most of the top free agents having found new homes – 12 of our top 15 have signed – the baseball transaction news figured to be light this week. Maybe the Yankees and Cody Bellinger would keep making lovey-dovey eyes at each other across the negotiating table to give us some headlines, but that felt like the only game in town for at least a few days. But just because no one is left to sign doesn’t mean nothing can happen. Out in Queens, the Mets weren’t content to sit pat after signing Bo Bichette. They continued their offseason splurge by acquiring Luis Robert Jr. from the White Sox in exchange for Luisangel Acuña and pitching prospect Truman Pauley, as ESPN’s Jeff Passan first reported.

I’ve grappled with evaluating Robert innumerable times over the past few years. For a while, he was a yearly feature in our Trade Value series, an electric talent in his early 20s. Then he became an interesting litmus test when talking to team evaluators, as his production dipped but his prodigious tools remained as loud as ever. Finally, as his contract hit the expensive team option phase, I considered him for a list of top free agents, as I have to predict what option decisions teams will make. At every turn, I came away equally impressed and frustrated by Robert’s ludicrous ceiling and subbasement-level floor.

You want a tooled-up center fielder? Robert is your guy. If you click on the “Prospects Report” tab on his player page, you’ll see this short blurb by Eric Longenhagen: “Graduation TLDR: The Vitruvian Outfield Prospect in all facets save for his approach, Robert graduated from prospectdom as one of baseball’s most exciting players.” That Vitruvian Outfield Prospect phrase has stuck with me.

If you made an outfielder in a lab, he’d look a lot like this. Power? Robert has 90th-percentile bat speed and clobbered 38 home runs in his last full season of playing time. He gets the ball in the air, too, all the better to maximize his best contact. Speed? You guessed it, 90th-percentile sprint speed. He’s also among the best defensive outfielders in the game when he’s healthy. He even has a strong throwing arm, though it’s inaccurate at times. If you’re looking for a Gold Glove defender who can hit 40 homers at the hardest outfield spot and swipe 30 bags, he’s one of maybe three players in the entire majors who fits the bill. Read the rest of this entry »

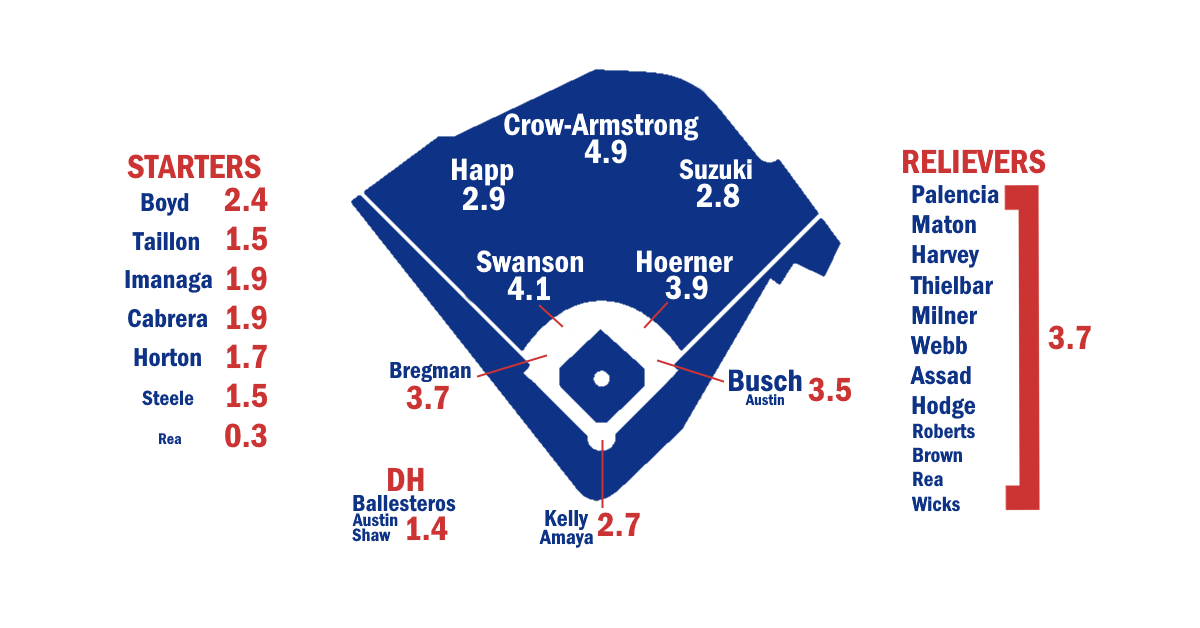

2026 ZiPS Projections: Chicago Cubs

For the 22nd consecutive season, the ZiPS projection system is unleashing a full set of prognostications. For more information on the ZiPS projections, please consult this year’s introduction, as well as MLB’s glossary entry. The team order is selected by lot, and the antepenultimate team is the Chicago Cubs.

Batters

ZiPS was a big believer in the 2025 Chicago Cubs, and it was right on point about most of their core talent. The problem, though, was that ZiPS wasn’t right about the Milwaukee Brewers, and though Chicago stayed in the NL Central race for most of the season, Milwaukee’s 14-game winning streak all but settled things by mid-August. Add in a five-game loss to the Brew Crew in the NLDS, and a successful season ended in underwhelming fashion for the North Siders. The Cubs went into the offseason looking to replace Kyle Tucker in the lineup and shore up the rotation a bit.

Generally speaking, the Cubs have a rather boring lineup in one manner: It’s mostly well-established players who are largely in the same roles as last season. Carson Kelly and Miguel Amaya, the latter swapped in for Reese McGuire, will be a competent tandem behind the plate. Dansby Swanson, Nico Hoerner, and Pete Crow-Armstrong will play terrific defense, with PCA adding a bunch of homers at the cost of a rather low on-base percentage. Ian Happ and Seiya Suzuki are on the wrong side of 30, but not distressingly so, and the typically B+ corner outfielders will likely put up their typical B+ seasons. One can see why the Cubs felt they could afford to trade Owen Caissie to Miami for Edward Cabrera; he was going to have a hard time finding playing time, and Kevin Alcántara’s defense makes him a more versatile fourth outfielder.

Where there are changes are at third base and designated hitter (by way of Suzuki playing a lot more right field). Alex Bregman is more or less the Kyle Tucker replacement, with a bit less bat and a bit more defensive value. Moisés Ballesteros has a lot of offensive upside, but he’s not really exciting yet as a full-time designated hitter, and Matt Shaw loses significant value as a DH. ZiPS is optimistic about Tyler Austin after a mostly successful six-year run in Japan, though he doesn’t provide a lot of flexibility, as it’s been years since he’s played anywhere but first base. I say mostly successful because he wasn’t particularly durable in NPB, with his most notable — and amusing — injury coming when he smashed his head on the dugout ceiling while changing his jersey.

I’m actually not quite sure what happens with Shaw, who appears to have been musical chaired out of a significant role by the Bregman and Austin signings. I don’t know just how seriously the Cubs consider him a supersub. Swanson and Hoerner were both durable in 2025, so we didn’t get any sneak peeks at how the Cubs truly felt about Shaw’s ability to play the middle infield when the rubber meets the road.

I wonder if the Cubs will be particularly active with non-roster invitations over the next month; ZiPS doesn’t see a great deal in the way of reinforcements in the high minors. Guys like Scott Kingery are probably far too high in the ZiPS WAR rankings than the Cubs ought to be comfortable with.

Pitchers

ZiPS sees the Cubs as having a very deep rotation that’s also very deep in unexcitement. There’s certainly some upside here, especially in Edward Cabrera, but ZiPS largely views the team as having a whole lot of broadly average starting pitching options. The good news here is that if Justin Steele has any setbacks, ZiPS likes the team’s replacement options. Even with especially bad luck in the injury department, the computer thinks Javier Assad will be adequate — it has him with an ERA considerably lower than his FIP, though some of that is thanks to the stellar Cubs defense — and that Ben Brown and Jordan Wicks would both be far more acceptable as starters if called into duty than they’ve shown so far. Heck, if Colin Rea or even Connor Noland were forced into starting some games, that wouldn’t be an apocalyptic scenario for the Cubs.

While deep in meh, ZiPS is more enthusiastic about the Chicago bullpen. Now, as was the case with Assad, some of the bullpen’s projected sufficiency comes down to the defense behind it, but ZiPS largely sees these relievers as having ERAs below four, and generally well below that line. ZiPS especially likes Hunter Harvey, Daniel Palencia, and the relief version of Porter Hodge. In the case of Hodge, remember the rule not to freak out about one-year home run totals for otherwise competent pitchers. The only prominent relievers ZiPS looks at with a bit of a side eye are Ethan Roberts and recent signee Jacob Webb.

All in all, the Cubs look like a team with a win total in the low 90s. The only negative of that projection is that ZiPS feels similarly about the Brewers this time around. We won’t know the end of this story for another nine months.

Ballpark graphic courtesy Eephus League. Depth charts constructed by way of those listed here. Size of player names is very roughly proportional to Depth Chart playing time. The final team projections may differ considerably from our Depth Chart playing time.

| Player | B | Age | PO | PA | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | BB | SO | SB | CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pete Crow-Armstrong | L | 24 | CF | 614 | 560 | 91 | 143 | 28 | 6 | 25 | 91 | 33 | 151 | 32 | 8 |

| Nico Hoerner | R | 29 | 2B | 634 | 580 | 82 | 161 | 28 | 3 | 9 | 62 | 40 | 57 | 26 | 6 |

| Dansby Swanson | R | 32 | SS | 601 | 543 | 78 | 131 | 24 | 2 | 19 | 71 | 52 | 155 | 14 | 3 |

| Michael Busch | L | 28 | 1B | 586 | 513 | 82 | 132 | 27 | 3 | 28 | 87 | 62 | 142 | 3 | 0 |

| Ian Happ | B | 31 | LF | 638 | 548 | 82 | 134 | 33 | 1 | 22 | 79 | 81 | 151 | 8 | 2 |

| Seiya Suzuki | R | 31 | RF | 601 | 525 | 74 | 136 | 27 | 4 | 26 | 86 | 67 | 150 | 7 | 3 |

| Alex Bregman | R | 32 | 3B | 568 | 491 | 71 | 118 | 24 | 1 | 18 | 70 | 65 | 83 | 2 | 1 |

| Matt Shaw | R | 24 | 3B | 530 | 470 | 69 | 115 | 21 | 4 | 16 | 65 | 49 | 105 | 19 | 6 |

| Moisés Ballesteros | L | 22 | C | 586 | 530 | 60 | 139 | 23 | 2 | 14 | 72 | 47 | 100 | 2 | 2 |

| Carson Kelly | R | 31 | C | 359 | 317 | 39 | 73 | 12 | 1 | 11 | 42 | 35 | 73 | 2 | 0 |

| Pedro Ramirez | B | 22 | 3B | 570 | 523 | 61 | 127 | 18 | 4 | 7 | 55 | 36 | 114 | 14 | 6 |

| Jonathon Long | R | 24 | 1B | 566 | 495 | 68 | 122 | 18 | 1 | 14 | 67 | 59 | 130 | 1 | 0 |

| Tyler Austin | R | 34 | 1B | 329 | 290 | 41 | 71 | 18 | 1 | 14 | 49 | 36 | 91 | 0 | 0 |

| Miguel Amaya | R | 27 | C | 267 | 238 | 27 | 57 | 12 | 1 | 7 | 35 | 19 | 58 | 0 | 0 |

| Jon Berti | R | 36 | 3B | 294 | 263 | 35 | 64 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 21 | 25 | 65 | 19 | 5 |

| Forrest Wall | L | 30 | CF | 370 | 326 | 49 | 76 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 36 | 34 | 106 | 23 | 5 |

| Kevin Alcántara | R | 23 | CF | 473 | 431 | 54 | 101 | 20 | 1 | 12 | 53 | 38 | 154 | 8 | 3 |

| Dixon Machado | R | 34 | 3B | 331 | 286 | 28 | 59 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 27 | 36 | 66 | 3 | 1 |

| Scott Kingery | R | 32 | SS | 380 | 346 | 41 | 71 | 11 | 3 | 9 | 38 | 26 | 127 | 8 | 1 |

| Carlos Santana | B | 40 | 1B | 449 | 389 | 46 | 83 | 15 | 0 | 12 | 51 | 54 | 87 | 4 | 0 |

| Reese McGuire | L | 31 | C | 235 | 214 | 21 | 47 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 27 | 14 | 51 | 1 | 0 |

| Hayden Cantrelle | B | 27 | 2B | 373 | 316 | 41 | 61 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 32 | 44 | 133 | 14 | 3 |

| Brett Bateman | L | 24 | CF | 425 | 370 | 45 | 84 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 31 | 48 | 103 | 12 | 4 |

| Chase Strumpf | R | 28 | 3B | 398 | 341 | 43 | 64 | 13 | 1 | 10 | 43 | 48 | 152 | 4 | 1 |

| Justin Dean | R | 29 | CF | 391 | 347 | 50 | 73 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 34 | 37 | 127 | 22 | 7 |

| Justin Turner | R | 41 | 1B | 419 | 365 | 44 | 88 | 18 | 0 | 9 | 44 | 41 | 79 | 2 | 1 |

| BJ Murray Jr. | B | 26 | 1B | 506 | 442 | 50 | 92 | 17 | 1 | 12 | 53 | 57 | 130 | 10 | 4 |

| Ariel Armas | R | 23 | C | 377 | 344 | 24 | 68 | 17 | 1 | 4 | 34 | 26 | 90 | 4 | 3 |

| Jefferson Rojas | R | 21 | SS | 480 | 432 | 55 | 89 | 13 | 3 | 9 | 48 | 38 | 102 | 11 | 3 |

| Ben Cowles | R | 26 | SS | 490 | 445 | 50 | 95 | 20 | 2 | 7 | 48 | 34 | 164 | 11 | 5 |

| Cameron Sisneros | L | 25 | 1B | 343 | 300 | 28 | 67 | 12 | 1 | 7 | 40 | 32 | 72 | 5 | 1 |

| Christian Bethancourt | R | 34 | C | 243 | 226 | 25 | 45 | 10 | 0 | 7 | 26 | 10 | 72 | 2 | 1 |

| James Triantos | R | 23 | 2B | 486 | 451 | 58 | 107 | 18 | 3 | 5 | 47 | 26 | 79 | 20 | 7 |

| Felix Stevens | R | 26 | RF | 383 | 344 | 41 | 69 | 14 | 1 | 13 | 49 | 32 | 155 | 2 | 1 |

| Pablo Aliendo | R | 25 | C | 367 | 336 | 33 | 64 | 14 | 1 | 10 | 43 | 21 | 147 | 1 | 1 |

| Caleb Knight | R | 30 | DH | 90 | 80 | 6 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 28 | 1 | 1 |

| Devin Ortiz | R | 27 | 3B | 479 | 429 | 47 | 92 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 40 | 38 | 112 | 8 | 4 |

| Parker Chavers | L | 27 | LF | 355 | 317 | 39 | 63 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 28 | 35 | 100 | 10 | 4 |

| Darius Hill | L | 28 | LF | 350 | 322 | 35 | 73 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 32 | 22 | 78 | 2 | 2 |

| Casey Opitz | B | 27 | C | 251 | 225 | 21 | 37 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 20 | 22 | 96 | 1 | 0 |

| Leonel Espinoza | R | 23 | CF | 454 | 419 | 54 | 93 | 14 | 2 | 6 | 44 | 25 | 125 | 12 | 5 |

| Reivaj Garcia | B | 24 | 2B | 413 | 384 | 41 | 91 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 31 | 19 | 82 | 6 | 2 |

| Carter Trice | R | 23 | CF | 374 | 328 | 41 | 59 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 43 | 41 | 139 | 8 | 4 |

| Drew Bowser | R | 24 | 3B | 328 | 293 | 32 | 52 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 29 | 30 | 132 | 6 | 2 |

| Miguel Pabon | R | 25 | C | 261 | 234 | 22 | 42 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 18 | 21 | 91 | 2 | 0 |

| Jordan Nwogu | R | 27 | LF | 376 | 342 | 39 | 71 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 38 | 23 | 123 | 12 | 5 |

| Edgar Alvarez | L | 25 | LF | 424 | 384 | 38 | 84 | 15 | 0 | 7 | 39 | 34 | 125 | 4 | 1 |

| Brian Kalmer | R | 25 | 1B | 351 | 317 | 36 | 60 | 11 | 2 | 10 | 37 | 30 | 130 | 1 | 0 |

| Eriandys Ramon | B | 23 | 3B | 226 | 215 | 22 | 38 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 19 | 9 | 76 | 2 | 2 |

| Haydn McGeary | R | 26 | DH | 398 | 353 | 32 | 69 | 12 | 1 | 7 | 38 | 38 | 141 | 3 | 0 |

| Alexis Hernandez | R | 21 | SS | 277 | 252 | 28 | 44 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 20 | 21 | 92 | 7 | 2 |

| Reginald Preciado | R | 23 | 3B | 335 | 313 | 29 | 60 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 26 | 15 | 110 | 5 | 3 |

| Jaylen Palmer | R | 25 | RF | 433 | 387 | 45 | 68 | 12 | 1 | 9 | 42 | 39 | 195 | 12 | 5 |

| Ethan Hearn | L | 25 | C | 319 | 294 | 29 | 52 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 33 | 19 | 124 | 3 | 1 |

| Luis Sanchez | L | 18 | CF | 253 | 231 | 23 | 37 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 19 | 16 | 77 | 6 | 4 |

| Christopher Paciolla | R | 22 | 3B | 251 | 235 | 16 | 40 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 10 | 89 | 3 | 2 |

| Andy Garriola | R | 26 | LF | 418 | 387 | 40 | 71 | 17 | 1 | 10 | 44 | 20 | 120 | 4 | 1 |

| Rafael Morel | R | 24 | LF | 397 | 356 | 43 | 64 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 31 | 32 | 152 | 10 | 2 |

| Ed Howard | R | 24 | SS | 305 | 284 | 23 | 49 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 18 | 16 | 124 | 4 | 2 |

| Player | PA | BA | OBP | SLG | OPS+ | ISO | BABIP | Def | WAR | wOBA | 3YOPS+ | RC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pete Crow-Armstrong | 614 | .255 | .304 | .461 | 118 | .206 | .307 | 13 | 4.6 | .326 | 122 | 88 |

| Nico Hoerner | 634 | .278 | .333 | .383 | 107 | .105 | .296 | 11 | 3.8 | .314 | 105 | 82 |

| Dansby Swanson | 601 | .241 | .309 | .398 | 104 | .157 | .304 | 10 | 3.6 | .309 | 99 | 71 |

| Michael Busch | 586 | .257 | .345 | .485 | 138 | .228 | .303 | 2 | 3.2 | .356 | 134 | 86 |

| Ian Happ | 638 | .245 | .345 | .429 | 123 | .184 | .299 | 3 | 2.9 | .338 | 117 | 84 |

| Seiya Suzuki | 601 | .259 | .343 | .474 | 134 | .215 | .315 | -2 | 2.9 | .350 | 129 | 88 |

| Alex Bregman | 568 | .240 | .336 | .403 | 114 | .163 | .256 | 2 | 2.7 | .325 | 109 | 67 |

| Matt Shaw | 530 | .245 | .321 | .409 | 110 | .164 | .284 | 1 | 2.4 | .319 | 112 | 68 |

| Moisés Ballesteros | 586 | .262 | .324 | .392 | 107 | .130 | .300 | -3 | 2.1 | .312 | 108 | 69 |

| Carson Kelly | 359 | .230 | .312 | .379 | 99 | .149 | .266 | 3 | 1.8 | .304 | 94 | 38 |

| Pedro Ramirez | 570 | .243 | .296 | .333 | 83 | .090 | .299 | 11 | 1.4 | .278 | 85 | 57 |

| Jonathon Long | 566 | .246 | .334 | .372 | 105 | .126 | .308 | 5 | 1.4 | .314 | 106 | 62 |

| Tyler Austin | 329 | .245 | .328 | .459 | 125 | .214 | .308 | 1 | 1.2 | .336 | 118 | 44 |

| Miguel Amaya | 267 | .239 | .309 | .387 | 101 | .148 | .289 | -2 | 0.9 | .306 | 99 | 28 |

| Jon Berti | 294 | .243 | .314 | .319 | 85 | .076 | .313 | 4 | 0.9 | .285 | 81 | 32 |

| Forrest Wall | 370 | .233 | .313 | .328 | 87 | .095 | .330 | 0 | 0.9 | .288 | 86 | 40 |

| Kevin Alcántara | 473 | .234 | .298 | .369 | 92 | .135 | .336 | -1 | 0.8 | .293 | 95 | 50 |

| Dixon Machado | 331 | .206 | .302 | .266 | 67 | .060 | .258 | 9 | 0.7 | .263 | 66 | 24 |

| Scott Kingery | 380 | .205 | .263 | .332 | 72 | .127 | .295 | 4 | 0.6 | .262 | 69 | 32 |

| Carlos Santana | 449 | .213 | .312 | .344 | 91 | .131 | .245 | 5 | 0.6 | .293 | 88 | 43 |

| Reese McGuire | 235 | .220 | .270 | .341 | 76 | .121 | .261 | 2 | 0.5 | .268 | 73 | 20 |

| Hayden Cantrelle | 373 | .193 | .304 | .285 | 73 | .092 | .318 | 3 | 0.5 | .272 | 73 | 31 |

| Brett Bateman | 425 | .227 | .318 | .286 | 77 | .059 | .307 | 2 | 0.5 | .277 | 78 | 38 |

| Chase Strumpf | 398 | .188 | .297 | .320 | 79 | .132 | .302 | 1 | 0.4 | .280 | 81 | 34 |

| Justin Dean | 391 | .210 | .294 | .305 | 75 | .095 | .316 | 2 | 0.4 | .271 | 74 | 39 |

| Justin Turner | 419 | .241 | .325 | .364 | 100 | .123 | .285 | 0 | 0.3 | .305 | 100 | 44 |

| BJ Murray Jr. | 506 | .208 | .302 | .333 | 84 | .125 | .267 | 7 | 0.3 | .285 | 87 | 48 |

| Ariel Armas | 377 | .198 | .265 | .288 | 61 | .090 | .256 | 5 | 0.2 | .249 | 64 | 28 |

| Jefferson Rojas | 480 | .206 | .277 | .313 | 71 | .107 | .249 | 0 | 0.2 | .263 | 77 | 41 |

| Ben Cowles | 490 | .213 | .278 | .315 | 72 | .101 | .321 | -1 | 0.0 | .264 | 73 | 43 |

| Cameron Sisneros | 343 | .223 | .312 | .340 | 89 | .117 | .271 | 1 | 0.0 | .291 | 94 | 33 |

| Christian Bethancourt | 243 | .199 | .234 | .336 | 63 | .137 | .259 | 1 | -0.1 | .247 | 59 | 19 |

| James Triantos | 486 | .237 | .284 | .324 | 76 | .087 | .278 | -2 | -0.1 | .269 | 81 | 48 |

| Felix Stevens | 383 | .201 | .277 | .360 | 83 | .159 | .318 | 0 | -0.3 | .281 | 88 | 35 |

| Pablo Aliendo | 367 | .190 | .251 | .327 | 66 | .137 | .302 | -3 | -0.4 | .255 | 72 | 28 |

| Caleb Knight | 90 | .188 | .270 | .263 | 56 | .075 | .275 | 0 | -0.4 | .245 | 58 | 6 |

| Devin Ortiz | 479 | .214 | .285 | .280 | 65 | .065 | .279 | 1 | -0.5 | .256 | 65 | 38 |

| Parker Chavers | 355 | .199 | .282 | .274 | 63 | .075 | .280 | 5 | -0.5 | .254 | 62 | 28 |

| Darius Hill | 350 | .227 | .281 | .317 | 73 | .090 | .290 | 3 | -0.5 | .265 | 73 | 30 |

| Casey Opitz | 251 | .164 | .244 | .249 | 44 | .085 | .264 | 1 | -0.5 | .226 | 48 | 14 |

| Leonel Espinoza | 454 | .222 | .276 | .308 | 69 | .086 | .302 | -3 | -0.6 | .259 | 75 | 40 |

| Reivaj Garcia | 413 | .237 | .275 | .292 | 65 | .055 | .299 | 0 | -0.6 | .250 | 65 | 33 |

| Carter Trice | 374 | .180 | .278 | .335 | 77 | .155 | .266 | -8 | -0.7 | .274 | 83 | 34 |

| Drew Bowser | 328 | .177 | .262 | .266 | 54 | .089 | .306 | -1 | -0.8 | .242 | 59 | 22 |

| Miguel Pabon | 261 | .179 | .255 | .239 | 45 | .060 | .284 | -3 | -0.9 | .228 | 47 | 15 |

| Jordan Nwogu | 376 | .208 | .271 | .301 | 66 | .093 | .305 | 2 | -0.9 | .256 | 69 | 32 |

| Edgar Alvarez | 424 | .219 | .285 | .313 | 74 | .094 | .306 | -2 | -0.9 | .267 | 74 | 35 |

| Brian Kalmer | 351 | .189 | .262 | .331 | 71 | .142 | .282 | 0 | -0.9 | .262 | 73 | 28 |

| Eriandys Ramon | 226 | .177 | .217 | .274 | 42 | .097 | .257 | 1 | -1.0 | .217 | 47 | 14 |

| Haydn McGeary | 398 | .195 | .279 | .295 | 67 | .100 | .302 | 0 | -1.1 | .258 | 70 | 30 |

| Alexis Hernandez | 277 | .175 | .243 | .246 | 43 | .071 | .261 | -4 | -1.2 | .223 | 50 | 17 |

| Reginald Preciado | 335 | .192 | .237 | .259 | 44 | .067 | .285 | 1 | -1.3 | .221 | 48 | 21 |

| Jaylen Palmer | 433 | .176 | .261 | .282 | 58 | .106 | .322 | 2 | -1.3 | .247 | 63 | 33 |

| Ethan Hearn | 319 | .177 | .238 | .293 | 53 | .116 | .276 | -8 | -1.4 | .236 | 59 | 22 |

| Luis Sanchez | 253 | .160 | .233 | .216 | 32 | .056 | .230 | -1 | -1.4 | .209 | 39 | 15 |

| Christopher Paciolla | 251 | .170 | .219 | .238 | 33 | .068 | .264 | -1 | -1.5 | .206 | 37 | 14 |

| Andy Garriola | 418 | .183 | .235 | .310 | 57 | .127 | .237 | 2 | -1.5 | .240 | 57 | 29 |

| Rafael Morel | 397 | .180 | .258 | .247 | 48 | .067 | .300 | 2 | -1.6 | .232 | 50 | 26 |

| Ed Howard | 305 | .173 | .221 | .211 | 27 | .038 | .302 | -3 | -1.9 | .197 | 32 | 15 |

| Player | Hit Comp 1 | Hit Comp 2 | Hit Comp 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pete Crow-Armstrong | Andre Dawson | Carlos González | Dan Gladden |

| Nico Hoerner | Steve Sax | Felix Millan | Whit Merrifield |

| Dansby Swanson | Juan Samuel | Bill Rigney | Casey Blake |