Imagine being a pitcher who has to face the Angels this year. It’s not hard to figure out which batter you most need to prepare for. When the Angels played the Cubs last night, Albert Pujols batted third, which is a lot less imposing in 2019 than it was in 2008. Shohei Ohtani had the night off, which meant that Tommy La Stella was the best non-Trout bat in the lineup. He’s having a good year, as Jay Jaffe noted, but unfortunately for him, he’s still Tommy La Stella. Cesar Puello batted fifth, and hey, good for him. Still, though — the scouting report was probably just Mike Trout written in various fonts over and over again.

It’s safe to say that every game the Angels play, the opposing team has spent a lot of time trying to work out a way to get Trout out. Los Angeles has a robust 109 wRC+ this year among non-pitchers, which sounds good until you realize that non-Trout Angels have a 100 wRC+. The team is scuffling — two games below .500 in a division where you might need 100 wins to topple the Astros, and potentially a little lucky to be there given their BaseRuns record. The pitching staff is essentially made of duct tape and fervent prayers — Ty Buttrey leads the staff in both fWAR and RA/9 WAR, and their starting rotation looks like a horror story told to kids to keep them from becoming Angels fans.

Amidst this chaos, this unending deluge of mediocrity, Mike Trout is putting together another masterpiece of a season. It’s boring to say, almost — his 180 wRC+ is both the fourth-highest in baseball and the lowest Trout has recorded in the last three years. Being one of the best players in baseball is old hat for him. Still, he’s improving his craft incrementally, slowly shoring up weaknesses and adding to strengths. His unintentional walk rate, a gaudy 19%, is the highest of his career. His strikeout rate, a minuscule 16%, has never been lower. Trout’s 2019 might be the best he’s ever hit, a crazy thing to say about undoubtedly the best player in baseball.

Baseball is largely a game of failure and limitations, which makes talking about Trout’s plate discipline feel somewhat surreal. Consider this — Trout has started making contact with basically everything he swings at in the strike zone. His zone contact rate of 94.9% is sixth in baseball and the highest of his career. That’s strange, because for the most part, guys who make contact with everything are contact hitters who sacrifice power to put the ball in play. David Fletcher and his .137 ISO top the list.

This makes a rough kind of sense — hitting everything you swing at in the strike zone means you are probably putting some tough pitches in play, and cutting down on your swing to make more contact means those swings generally have less behind them. That, at least, is the logic that constrains mortals. Mike Trout started hitting everything in the strike zone, and he’s still slugging .600. That slugging percentage might be selling Trout short — he has the highest xSLG (a Baseball Savant statistic that predicts slugging percentage from angle and speed of hits) of his career, a gaudy .643.

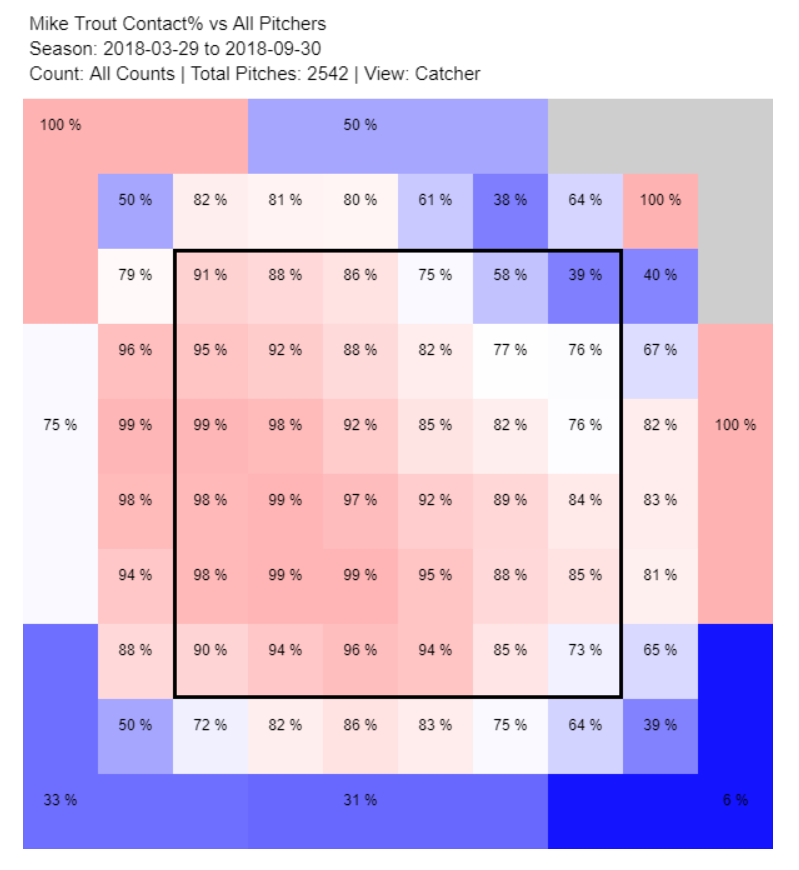

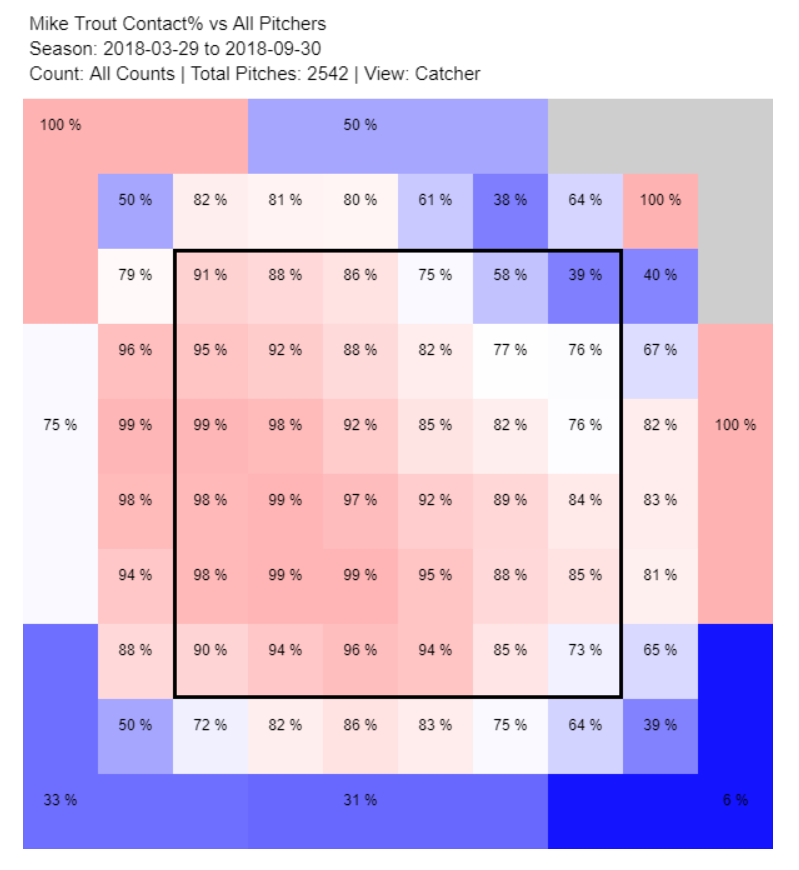

What does making contact with every pitch in the strike zone look like? Well, in 2018, Trout was great, but he was great while being only very good against high and outside pitches. Take a look at the upper righthand corner of this chart, the percentage of swings he made contact on by zone in 2018:

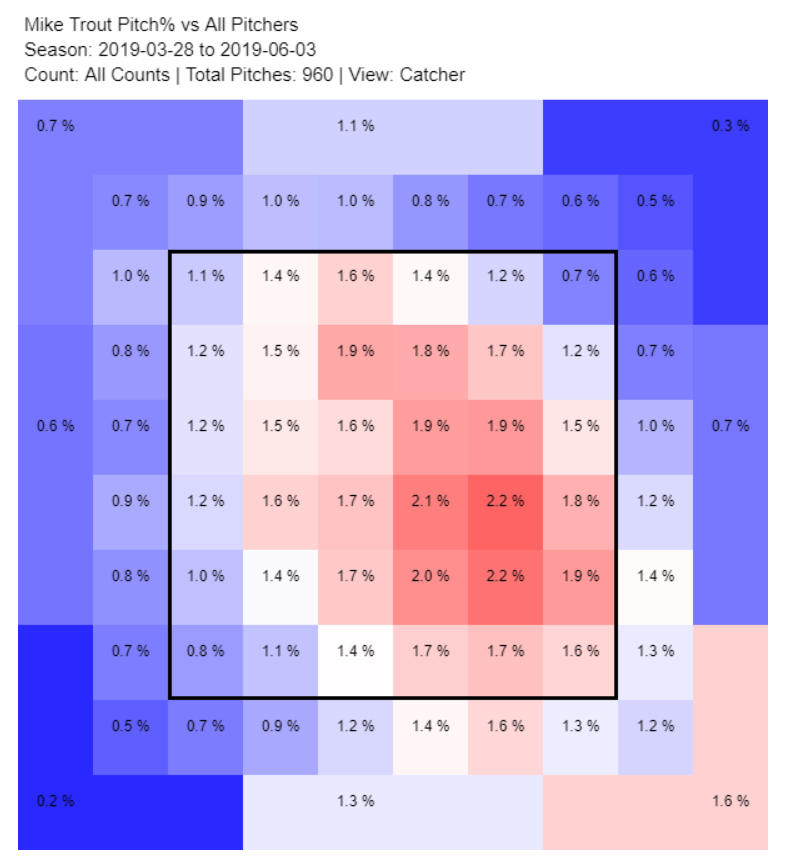

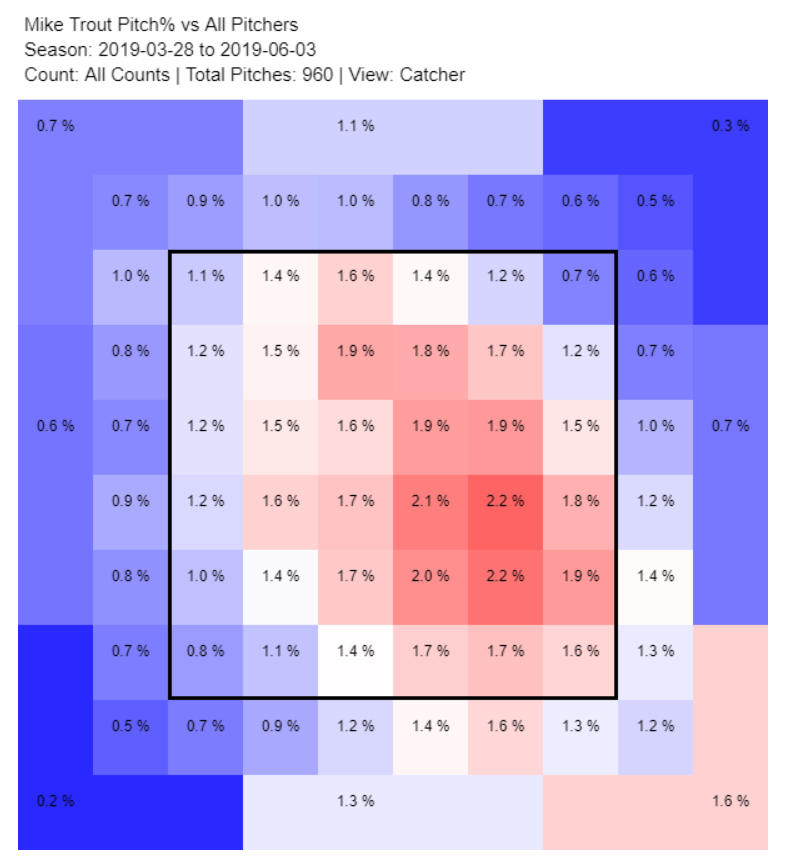

Pitchers know about this marginal weakness, and they do their best to exploit it. The book on Trout is to get him high and away. Take a look at where pitchers are attacking him in 2019:

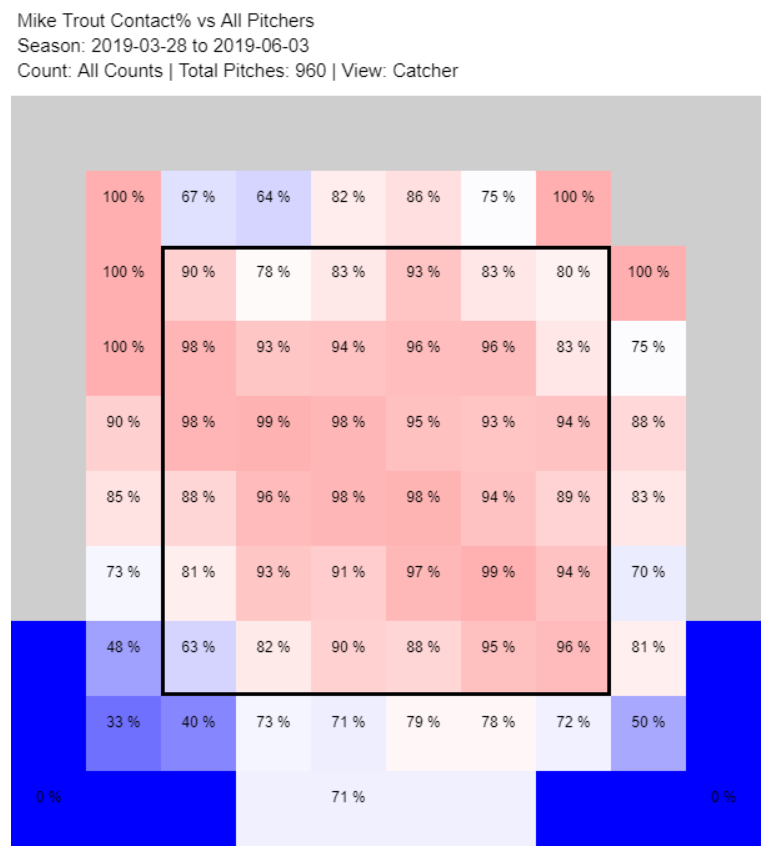

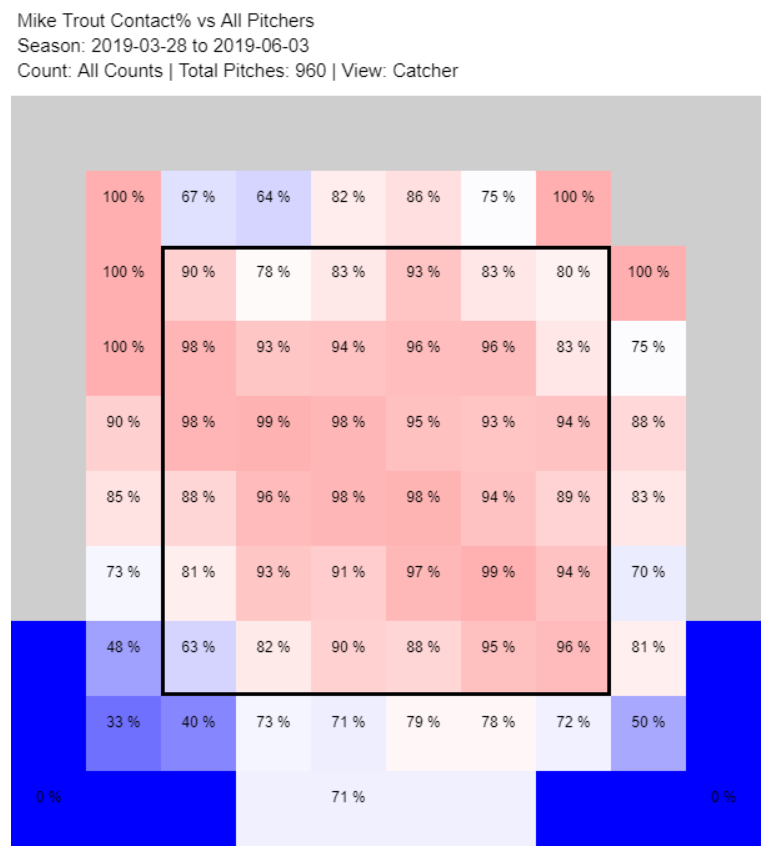

That’s good pitching right there. Find out where a hitter is most likely to get bad results, and aim for that spot. Maybe their focal point is a little too low, but the general idea of throwing away is certainly easy to see. Major league pitchers are tremendously skilled, and they spend countless hours perfecting their craft. That should work out to their advantage, right? Well, bad news, pitchers — this is Mike Trout we’re talking about here. Look at his contact rate in 2019:

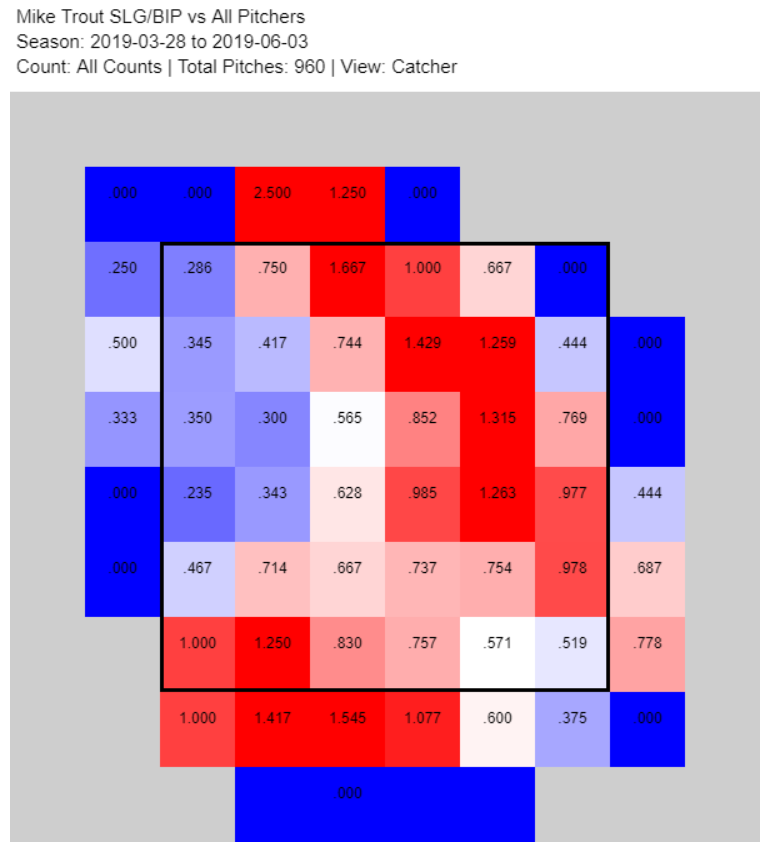

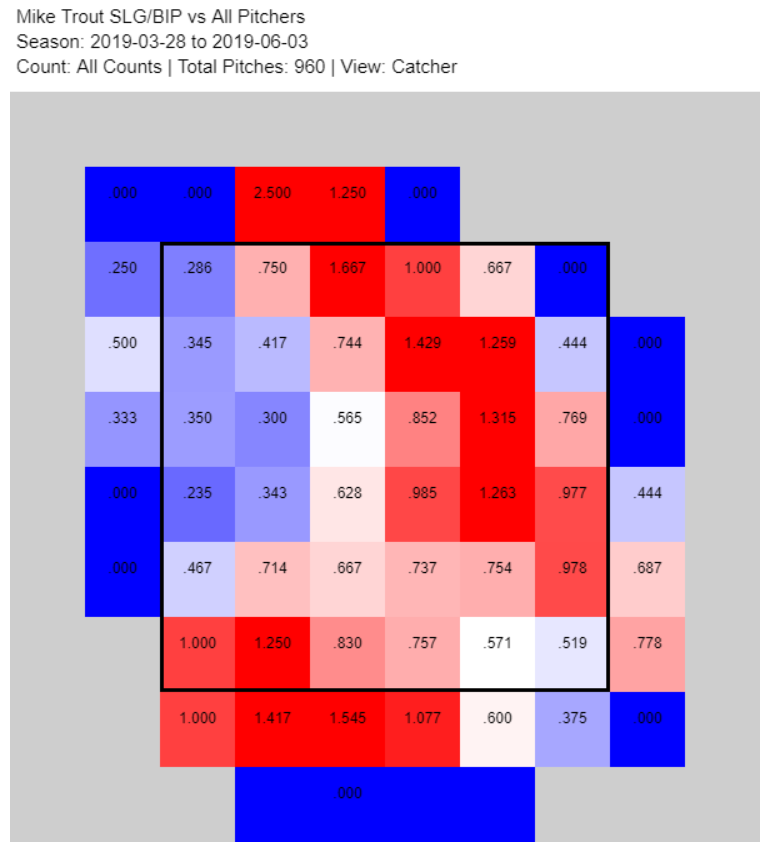

It would be one thing to protect a weak point in your swing with some defensive hacks. Plenty of good hitters punch outside pitches the other way, sacrificing power for contact on pitches that are hard to drive. Again, though, Mike Trout isn’t “plenty of good hitters.” He’s the best hitter in baseball. Trout is punishing outside and high pitches in 2019, doing a tremendous amount of damage when he puts the ball in play:

You’re reading this chart right — Trout is now getting his greatest production on balls in play in the very part of the strike zone where pitchers are attacking him most. That, in a nutshell, is what pitching to Trout is like. You might think you’re attacking a weakness, doing your research to put yourself in an advantageous position. Trout’s better at adapting than you are; he’s better than everyone. He reacts to your changes faster than he can be solved.

Pitch location isn’t the only part of Trout’s plate discipline pitchers have focused on this year. They’ve changed how they attack him on the first pitch of a plate appearance, and Trout is yet again using that to his advantage. For years, the book on Trout was that he was patient on the first pitch to the point of somnolence; he basically never swung at first-pitch breaking balls, for instance. Over the past few years, Trout has turned this trend around, becoming increasingly aggressive on the first pitch — he swung at 19.7% of first pitches in 2017 and 18.3% in 2018, the two highest rates of his career.

To combat this trend, pitchers are going out of the zone on first pitches more than they ever have. Trout is seeing strikes on 47% of first pitches, down from his career average of 55% and below the major league average of 51%. This adjustment was largely out of self-preservation. Trout slugged 1.061 with a .485 batting average when he put the first pitch into play last year. He hit five home runs on first pitches, a career high. Sticking with get-me-over first pitch fastballs was no longer an option.

In classic Trout fashion, though, he’s turned pitchers’ adjustments into another tool in his tool belt. Now that pitchers throw him fewer first-pitch strikes, he’s simply swinging less. He’s down to a 17% swing rate on first pitches this year while still swinging at 27% of pitches in the zone. He’s also missing less — he’s swung and missed at five first pitches this year, a 2% rate that would be his lowest since 2015, the last year of his extreme passivity on first pitches. Between this improved swing discipline and pitchers avoiding the zone like the plague, Trout is falling behind in the count 52.9% of the time this year, a career low and 5.2% below last year’s level.

2019 is arguably Mike Trout’s finest batting season so far. His xwOBA of .473 is the highest it’s ever been and 30 points higher than his wOBA, suggesting that he’s been unlucky this year to put up “only” a 180 wRC+, the third-highest of his career. He has the highest walk rate in baseball and a strikeout rate in the lowest 21% of qualified batters. He’s getting on base at the highest rate in his career despite the lowest BABIP in his career (excluding his brief 2011). The two changes pitchers have made to how they approach him this year sure don’t seem to have worked.

Pitchers will try to make other adjustments. They’ll start challenging him in the strike zone more on the first pitch — maybe with offspeed pitches, something that pitchers mostly haven’t tried yet. They’ll aim inside, where Trout’s power is down this year. They’ll continue to hunt holes in his game, small edges that they can use to blunt Trout’s effectiveness.

But until I see some evidence to the contrary, I don’t think it will matter. Pitchers can adjust all they want, try any gambit they’d like. For the most part, it seems like adjusting to beat Trout only plays into his hands. Someday, Mike Trout will grow old. He’ll slow down, get worse at recognizing pitches, stop instilling terror into opposing pitchers the way he does now. That day still feels infinitely far off, though. For now, he’s three steps ahead, putting up unreal numbers while shrugging off regression. Pitchers can plan all they want. Trout won’t stop laughing his way around the bases any time soon.