St. Louis continued to set the bar for consistently solid, never-lousy baseball teams. (Photo:

Jonathan Cutrer)

“I am, as I’ve said, merely competent. But in an age of incompetence, that makes me extraordinary.” – Billy Joel

The Cardinals are never really thought of as a small-market franchise, but in terms of the size of its media market — which is where the money comes from — St. Louis ranks between Cleveland and Pittsburgh. Yet historically, the Cardinals have been able to punch above their weight, and built a fanbase much larger than you would expect from the size of the city.

One of the ways they’ve been able to do this is by building a consistent culture of winning. They don’t always make the playoffs, but the Cardinals are rarely a lousy team. There’s almost certainly no one alive who remembers a 100-loss Cardinals squad, unless I’m drastically underestimating the probability that one of the few remaining 116-year-olds was a Cardinals fan in 1908. The last time the team even lost 90 games was nearly 30 years ago, in 1990. And while I roll my eyes at the Best Fans in Baseball business, during the team’s three-year stretch without a playoff appearance from 2016-18, their longest drought in 20 years, attendance at Busch Stadium was practically unchanged.

Since John Mozeliak, now the team’s president of baseball operations, was named general manager after the 2007 season, the Cards have reached the Platonic ideal of Cardinalia. Only once has a Moz-led team finished below 85 wins, but even in the 100-win season, the team didn’t feel like an unstoppable juggernaut; no Cardinal that year garnered serious MVP or Cy Young support. Instead, the team projected steady competence.

The Setup

The St. Louis Cardinals have been baseball’s most consistently above-average team in recent years. But how does one measure that above-averageness? I like to set 90 wins as kind of the benchmark for a very-good-yet-not-great team; like most humans, I’ve been programmed to like pretty numbers that end in zero. And since Mozeliak took over from Walt Jocketty, the Cardinals have been the closest to the 90-win mark year in and year out:

Above-Averagest Teams, 2008-19

| Team |

Average Deviation From 90 Wins |

| Cardinals |

3.5 |

| Dodgers |

6.2 |

| Yankees |

6.3 |

| Rays |

6.9 |

| Red Sox |

8.3 |

| Rangers |

8.4 |

| Brewers |

9.2 |

| Angels |

9.3 |

| Giants |

9.3 |

| Braves |

9.6 |

| Indians |

10.3 |

| Mets |

10.7 |

| Blue Jays |

10.9 |

| Athletics |

11.6 |

| Nationals |

11.8 |

| Diamondbacks |

12.4 |

| Cubs |

12.6 |

| Tigers |

12.8 |

| Phillies |

13.0 |

| Rockies |

14.0 |

| Reds |

14.1 |

| White Sox |

14.1 |

| Twins |

14.2 |

| Mariners |

14.7 |

| Pirates |

15.3 |

| Royals |

16.0 |

| Marlins |

16.8 |

| Padres |

16.9 |

| Orioles |

17.6 |

| Astros |

17.8 |

In a dozen years, the Cardinals missed 90 wins by a total of 42 wins. The 2019 Detroit Tigers missed 90 wins by a larger margin in a single year! And it’s not just chance either; in the 12 years of ZiPS projected standings, the Cardinals had the smallest difference between their 10th and 90th percentile win projections in six of 12 seasons. At the top end, only a single Cardinal since 2014 has been in the top five in the NL in WAR for a pitcher or a hitter: low-key NPB pickup Miles Mikolas in 2018. And by the same token, the Cardinals lows are quite high; only two teams in baseball received fewer replacement-level plate appearances or batters faced than the Cardinals:

Replacement-Level Performances, 2008-19

| Team |

PA/TBF |

WAR |

| Rays |

21282 |

-45.4 |

| Yankees |

22471 |

-46.7 |

| Cardinals |

24220 |

-54.0 |

| Indians |

28238 |

-59.5 |

| Blue Jays |

29600 |

-59.9 |

| Brewers |

29850 |

-60.4 |

| Athletics |

27082 |

-61.4 |

| Red Sox |

25064 |

-61.5 |

| Dodgers |

24830 |

-64.0 |

| Cubs |

27649 |

-64.1 |

| Twins |

33043 |

-64.6 |

| Nationals |

28037 |

-66.5 |

| Mets |

29313 |

-66.6 |

| Giants |

32272 |

-67.9 |

| Rangers |

28176 |

-68.1 |

| Angels |

28560 |

-69.8 |

| Diamondbacks |

31580 |

-70.8 |

| Tigers |

31256 |

-71.3 |

| Astros |

32677 |

-71.8 |

| Phillies |

32365 |

-73.1 |

| Braves |

29945 |

-74.8 |

| Royals |

34948 |

-77.0 |

| White Sox |

32953 |

-79.0 |

| Reds |

33919 |

-79.1 |

| Padres |

35047 |

-80.0 |

| Orioles |

36701 |

-84.2 |

| Rockies |

39341 |

-85.8 |

| Mariners |

38162 |

-90.6 |

| Pirates |

36930 |

-91.8 |

| Marlins |

34707 |

-92.8 |

After the 2018 season, their third straight year without postseason baseball, St. Louis had a new problem: how do you shake up this situation? And, from the point of view of the people paying the salaries, how do you make that happen without spending $300 million on a Bryce Harper or a Manny Machado? As with Matt Holliday and Jason Heyward, the Cardinals decided to aggressively acquire a star before signing him to a long-term extension. This worked well with Holliday, as the team was able to re-sign him after he hit free agency; they had less success keeping Heyward, a failure that, in hindsight, I’m sure they’re positively giddy about.

This time, the big move was Paul Goldschmidt, who had a year left on his contract. The price was steep, with Luke Weaver and Carson Kelly looking like real major leaguers, but it was a refreshing gamble from a team that tends to go the safe ‘n’ sensible route. Let’s name all the first basemen who were worth more wins from 2013-18:

…

[crickets]

So, the Cardinals expected they had secured their plug-and-play offensive powerhouse. The winter was quiet otherwise, with the team’s other big pickup being Andrew Miller, formerly of the Cleveland Indians. There was a real need for added bullpen depth, as the team’s relief corps struggled in 2018, ranking 26th in bullpen WAR. Miller was just as eager to wipe out memories from the previous season, one in which his ERA rose to 4.24 and his FIP to 3.51, both worsts since the Red Sox converted him to relief in 2012. The hope was that Miller, along with continued improvement from flamethrowing standout Jordan Hicks, would give the Cards a potent one-two punch in the bullpen.

The Projection

ZiPS projected St. Louis to finish a close second behind the Chicago Cubs, with a mean projection of 86 wins. While a few years ago it looked like the NL Central would struggle against the Cubs juggernaut, that team’s frugal payroll strategy and weakening farm system left them more of a jugger-not. (Yes, I’m ashamed of that sentence.)

There was no concern about their first-base acquisition, with ZiPS projecting a .270/.379/.479, 4.4 WAR line for Goldschmidt, putting him behind only Freddie Freeman and Cody Bellinger. ZiPS thought the Cardinals had a two-win player at every single position in the lineup, plus Jose Martinez and Tyler O’Neill.

But ZiPS had concerns about the rotation. The computer projected Carlos Martinez to be the team’s best starting pitcher, but due to injury, he was ticketed for the bullpen. The system was skeptical of both Michael Wacha, who was coming off 2018 injuries, and Dakota Hudson and his big fastball but erratic command.

The Results

The season got off to an auspicious start before it even actually began when St. Louis was able to sign Goldschmidt to an extension a week before Opening Day. And while the Cardinals eventually won 91 games — an unsurprising result for the eternal 90-win team — the specific events that got them the NL Central title were far from anticipated.

Imagine you woke up from a coma in November, were unable to access the internet, and asked me to tell you how the Cardinals did in 2019. Now, let’s say I was a bit of a jerk, and rather than just telling you the team’s record, I detailed the list below and made you guess how many wins the team ended up with:

- Paul Goldschmidt had his worst year since 2012, hitting .260/.346/.476, and failing to hit the three-win threshold despite playing in 161 games.

- Matt Carpenter struggled all year, hit .226, and ended up with 1.2 WAR.

- Michael Wacha had shoulder problems and an ERA near five.

- Carlos Martinez never got back into the rotation.

- Harrison Bader regressed significantly.

- Jordan Hicks needed Tommy John surgery.

- Miles Mikolas went from leading the NL in wins to leading the NL in losses.

- Jedd Gyorko barely avoided being released.

- Yadier Molina had his worst OPS since 2007. [2010 -DS]

- Andrew Miller pitched even worse than he did in 2018.

At this point, the doctors would kindly-yet-firmly ask me to stop, as you cried out, “Sweet mother of mercy, are we the Orioles now?”

But nope! 91 wins.

St. Louis needed a lot of quality production to win the division, even as one of the baseball’s weaker ones, but it was largely from unexpected places.

Jack Flaherty becoming a serious Cy Young candidate was a monster addition to the roster. I still like Luke Weaver, but appears the Cardinals picked the right young starting pitcher to send to Arizona.

And despite the setbacks to Miller and Hicks, the bullpen was a real plus for the team in 2019. Martinez may not have made it back to the rotation, but he stayed healthy after his May return and earned his 2.86 FIP. Giovanny Gallegos — one of ZiPS’s favorite little-known pitchers entering the season, who was projected for a 137 ERA+ (24th among all pitchers in baseball) — actually beat that lofty forecast. Fringe prospect Tommy Edman came up midseason, hit .304/.350/.500 while playing multiple positions, and finished the year worth more wins than Goldschmidt, Marcell Ozuna, or Carpenter.

The Cardinals rode into the playoffs and advanced to the NLCS after beating the Braves in an exciting five-game series, capped off with a 13-1 shellacking in Game 5 so forceful it might have knocked Atlanta out of the 2020 playoffs as well. But what the team did to poor Mike Foltynewicz didn’t continue against the Nationals, as the offense was shut down by Stephen Strasburg, Max Scherzer, and Anibal Sanchez.

What Comes Next?

It has been an exciting winter around baseball so far, but a very quiet one in St. Louis. The team extended a qualifying offer to Ozuna, but they don’t appear to be among the leaders bidders for his services. The team’s luxury tax number is around $179 million, and they have shown little inclination to push towards the $208 million limit. It’s likely the Cardinals will make a few lower-key free agent signings in the next two months — their signing on Tuesday of Korean left-handed pitcher Kwang-Hyun Kim is a start — but with the club having few gaping holes, it’s unlikely there will be any serious upgrades among those.

While that sounds like horrible news for the Cardinals and their fans, it’s unlikely they’ll will be punished for not being more financially aggressive. The Brewers, two games behind the Cardinals in 2019, have shown no movement towards a big-spending winter. And if the Cards and Brewers are being thrifty, the Cubs are being an unrepentant Ebenezer Scrooge, focusing less on how to get more outfield offense and more on finding trade partners for Kris Bryant. Pittsburgh is rebuilding, and while the Reds will likely improve to relevance — and have the best pitching staff in the division — the lineup is still a work in progress. Even treading water, St. Louis still looks to have one of the fastest boats in the division.

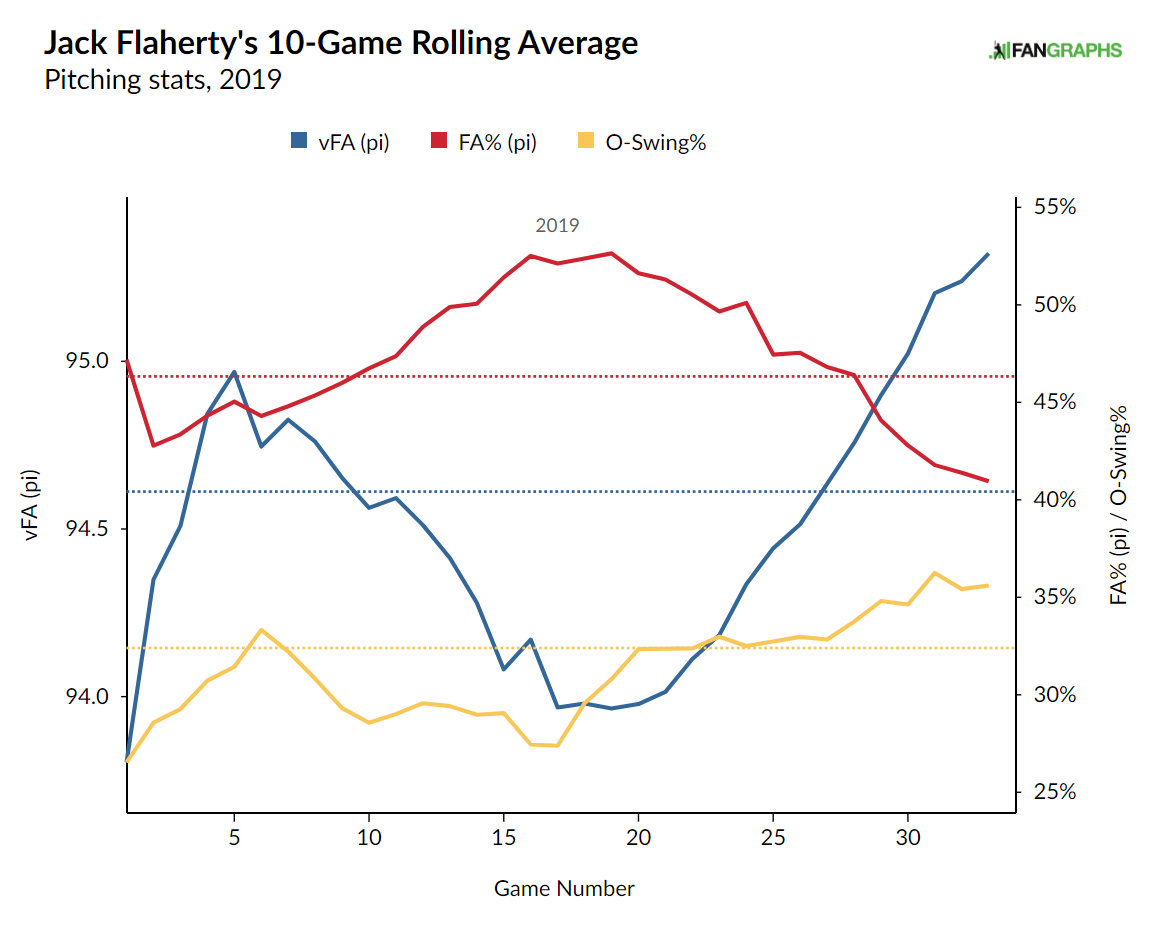

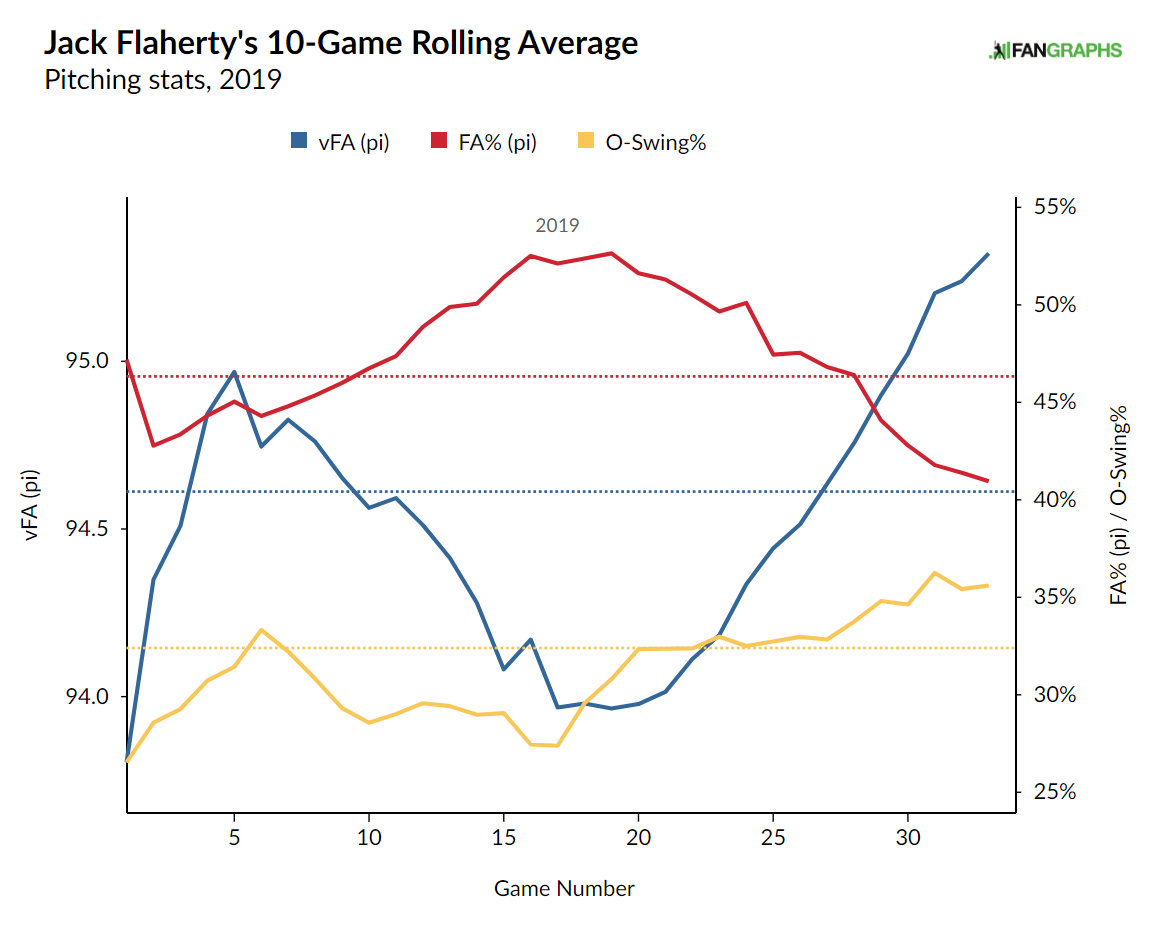

2020 ZiPS Projection – Jack Flaherty

How about some good ol’ fashioned fan service? If the season had lasted two months longer, it might have been Flaherty who ended up with the Cy Young award. He was a monster after the All-Star break, putting up a comically low 0.91 ERA and 2.22 FIP in the second half. Much of St. Louis’s late-season surge was due to the fact that Flaherty didn’t have a single bad game after early July. His improvement was largely the result of him developing a better feel for the rest of his repertoire. As he threw fewer fastballs, he saw both an uptick in velocity and an greater ability to get hitters to offer at pitches out of the zone. Being less fastball-reliant made Flaherty the best version of himself.

My colleague Craig Edwards went into greater detail the change in Flaherty’s approach that helped him get into baseball’s elite tier.

ZiPS Projection – Jack Flaherty

| Year |

W |

L |

ERA |

G |

GS |

IP |

H |

HR |

BB |

SO |

ERA+ |

WAR |

| 2020 |

13 |

7 |

3.13 |

33 |

33 |

189.7 |

146 |

23 |

54 |

236 |

131 |

4.4 |

| 2021 |

13 |

7 |

3.04 |

34 |

34 |

192.7 |

146 |

23 |

54 |

240 |

136 |

4.7 |

| 2022 |

13 |

7 |

3.02 |

33 |

33 |

187.7 |

141 |

22 |

52 |

236 |

136 |

4.6 |

| 2023 |

12 |

6 |

3.03 |

30 |

30 |

172.3 |

129 |

21 |

47 |

217 |

136 |

4.2 |

| 2024 |

11 |

6 |

2.95 |

29 |

29 |

167.7 |

124 |

20 |

46 |

215 |

139 |

4.2 |

| 2025 |

11 |

6 |

2.96 |

28 |

28 |

161.3 |

118 |

20 |

44 |

210 |

139 |

4.1 |

As far as regressions go, that’s a fairly mild one. 4.4 WAR is within a win of both Jacob deGrom and Scherzer, both pitchers who are rumored to be at least adequate at this baseball stuff. Jack Flaherty is a legitimate ace, even when his career .254 BABIP inevitably rises.

![]() iTunes Feed (Please rate and review us!)

iTunes Feed (Please rate and review us!)![]() Sponsor Us on Patreon

Sponsor Us on Patreon![]() Facebook Group

Facebook Group![]() Effectively Wild Wiki

Effectively Wild Wiki![]() Twitter Account

Twitter Account![]() Get Our Merch!

Get Our Merch!![]() Email Us: podcast@fangraphs.com

Email Us: podcast@fangraphs.com

Kiley McDaniel

Kiley McDaniel