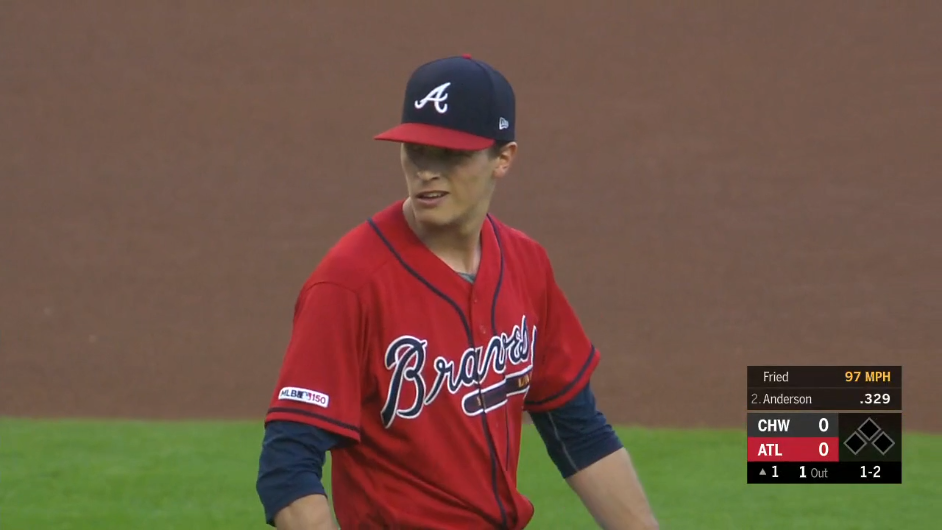

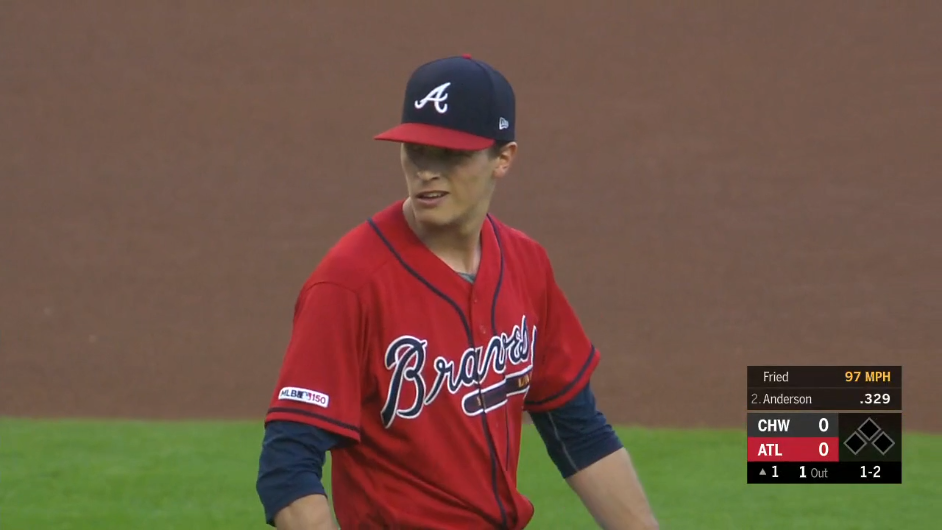

Last Thursday, Max Fried turned in six of the best innings of his young career. Sure, it was against the Chicago White Sox, who are decisively not good at hitting baseballs right now, but still, Fried was dominant. He sat down each of the first 13 hitters he faced, striking out eight of them. Then Eloy Jiménez reached on a softly hit infield single down the third-base line and scored two batters later on a double by Adam Engel. But Fried bounced right back with a scoreless sixth, striking out two more to bring his total for the day to 11. He waved four batters with a curveball, four with a slider, and three with a fastball. After one of them, he made this face.

Folks, I have never looked at anyone like that in my life. Mostly because I have never fired a 97 mph fastball past Tim Anderson, or accomplished anything else that would fill me with a similar rush of adrenaline and personal gratification. Maybe if I really think I did a great job writing this post, I’ll feel so good about it that I’ll slam my laptop shut, strut away from the couch, and make this face at my girlfriend. Probably not, but we’ll see how these next few hundred words go. Might be worth a try. Point is, Fried was feeling himself, and I don’t blame him.

Then it all went away. Jiménez singled again on the first pitch of the seventh inning, this time hitting a 105-mph line drive to right. Then Fried let a 1-2 breaker run in and hit James McCann, and then Yolmer Sanchez reached on an error at first base. After that, Fried was out of the game, and two batters later, he watched Braves reliever Luke Jackson surrender a three-run homer to Welington Castillo, scoring all of the runners he inherited. After allowing just one run on three hits and a walk in his first six innings, Fried allowed all three hitters he faced in the seventh reach, and each one subsequently scored, messing up what had been a very strong performance. Read the rest of this entry »

Dan Szymborski

Dan Szymborski