We’re just a week away from actual major league baseball games and two weeks from Opening Day, and the free agent market is about spent. Dallas Keuchel and Craig Kimbrel remain free agents for now, the only two available players projected for two or more WAR on our depth charts. Even lowering the bar to a single win only adds two additional names in Carlos Gonzalez and Gio Gonzalez.

Unless your team is willing to sign Keuchel or Kimbrel, any improvements will have to be made via a trade. And since pretty much every team could use an improvement somewhere, it’s the best time of the year for a bit of fantasy matchmaking until we get to post-All Star Week.

Note that these are not trades I predict will happen, only trades I’d like to see happen for one reason or another. Until I’m appointed Emperor-King of Baseball, I have no power to make these trades happen.

—

1. Corey Kluber to the San Diego Padres for Wil Myers, Josh Naylor, Luis Patino, and $35 million.

One of the reasons the Kluber trade rumors so persistently involved the Padres this winter is because it made so much sense. The idea was that Cleveland had a deep starting rotation and an offense that looked increasingly like that of the Colorado Rockies, with a couple of MVP candidates and abundant quantities of meh elsewhere.

On the Padres side, the team’s lineup looked nearly playoff-viable in a number of configurations with the exception of a hole at third base. The team was awash in pitching prospects but had a drought of 2019 rotation-ready candidates.

These facts have largely stayed unchanged with the obvious exception of San Diego’s hole at third base. The Padres aren’t far away from contending, and while signing Keuchel is cleaner, revisiting Kluber is a bigger gain.

At four years and $28 million guaranteed after the trade’s cash subsidy, Myers actually has some value to the Indians, who have resorted to fairly extreme measures like seriously considering Hanley Ramirez for a starting job. Most contenders aren’t upgraded by a league-average outfielder/DH, but the Indians would be. Cleveland can’t let Kluber get away without taking a top 50ish prospect, and Naylor is a lot more interesting on a team like the Indians, which has a lot of holes on the easy side of the defensive spectrum, than he is on one that wants to be in the Eric Hosmer business for a decade.

Unfortunately, in the end, I expect that Cleveland wasn’t as serious about trading Kluber as they were made out to be and would likely be far more interested in someone who could contribute now, like Chris Paddack. And Paddack makes the trade make a lot less sense for the Padres, given that they have enough holes in the rotation that they ought to want Kluber and Paddack starting right now.

—

2. Nicholas Castellanos to the Cleveland Indians for Yu Chang, Luis Oviedo, and Bobby Bradley.

The relationship between Castellanos and the Tigers seems to oscillate between the former wanting a trade and both sides wanting to hammer out a contract extension.

Truth is, trading Castellanos always made more sense as the Tigers really aren’t that close to being a competitive team yet, even in the drab AL Central. Castellanos is not a J.D. Martinez-type hitter, and I feel Detroit would be making a mistake if lingering disappointment from a weak return for Martinez were to result in them not getting value for Castellanos.

While one could envision a future Indian infield where Jose Ramirez ends up back at second, and Chang is at third (or second), I think the need for a hitter, even if the first trade proposed here were to happen, is too great. Oviedo is years away and Cleveland’s window of contention can’t wait to see if Bradley turns things around.

—

3. Dylan Bundy to the New York Mets for Will Toffey and Walker Lockett.

I suspect that if the Mets were willing to sign Dallas Keuchel, he’d already be in Queens. In an offseason during which the Mets lit up the neon WIN NOW sign, they’ve confusingly kept the fifth starter seat open for Jason Vargas for no particular reason.

Rather than wait for Vargas to rediscover the blood magicks that allowed him to put on a Greg Maddux glamour for a few months a couple of years ago, I’d much rather the Mets use their fifth starter role in a more interesting way. Bundy has largely disappointed, but there’s likely at least some upside left that the Orioles have shown little ability to figure out yet.

Toffey would struggle to get at-bats in New York unless the team’s plethora of third-base-capable players came down with bubonic plague, and given that the team isn’t interested in letting Lockett seriously challenge Vargas’ role, better to let him discover how to get lefties out on a team that’s going to lose 100 games.

—

4. Mychal Givens to the Boston Red Sox for Bryan Mata.

Boston’s bullpen was a solid group in 2018, finishing fifth in FIP and ninth in bullpen WAR. But it’s a group that is now missing Kimbrel and Joe Kelly, two relievers who combined for 2.2 of the team’s 4.9 WAR. The Red Sox haven’t replaced that lost production, and while they talk about how they really think that Ryan Brasier is great, they already had him last year. Now he’ll throw more innings in 2019, but that will largely be balanced by him not actually being a 1.60 ERA pitcher.

The Red Sox have dropped to 22nd in the depth chart rankings for bullpens, and although ZiPS is more optimistic than the ZiPS/Steamer mix, it’s only by enough to get Boston to 18th.

The Orioles are one of the few teams who might possibly be willing to part with bullpen depth at this point in the season and Givens, three years from free agency, gives the Red Sox the extra arm they need. Mata is a fascinating player, but he’s erratic and Boston needs to have a little more urgency in their approach. The O’s have more time to sort through fascinatingly erratic pitchers like Mata and Tanner Scott.

—

5. Madison Bumgarner to the Milwaukee Brewers for Corey Ray and Mauricio Dubon.

You know that point at a party when the momentum has kinda ended and people have slowly begun filtering to their cars or Ubers, but there’s one heavily inebriated dude who has decided he’s the King of New Years, something he proclaims in cringe-worthy fashion to the dwindling number of attendees?

That’s the Giants.

The party is over in San Francisco, with the roster not improved in any meaningful way from the ones that won 64 and 73 games in each of the last two seasons. The Giants are probably less likely to win 90 games than George R. R. Martin is to finish The Winds of Winter before the end of the final season of Game of Thrones.

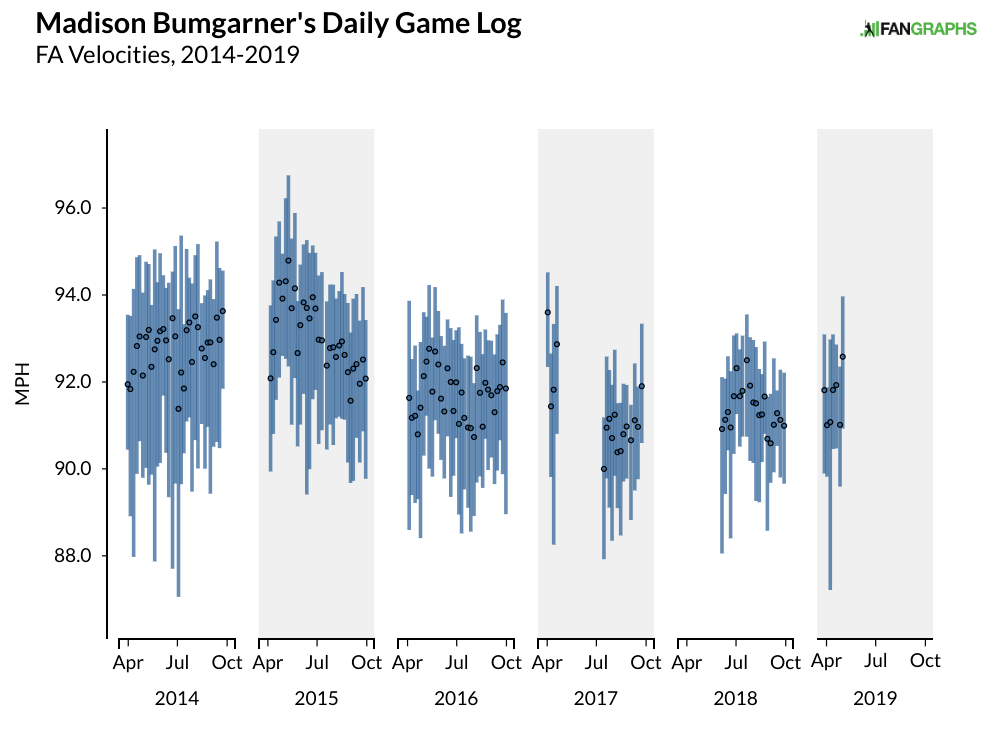

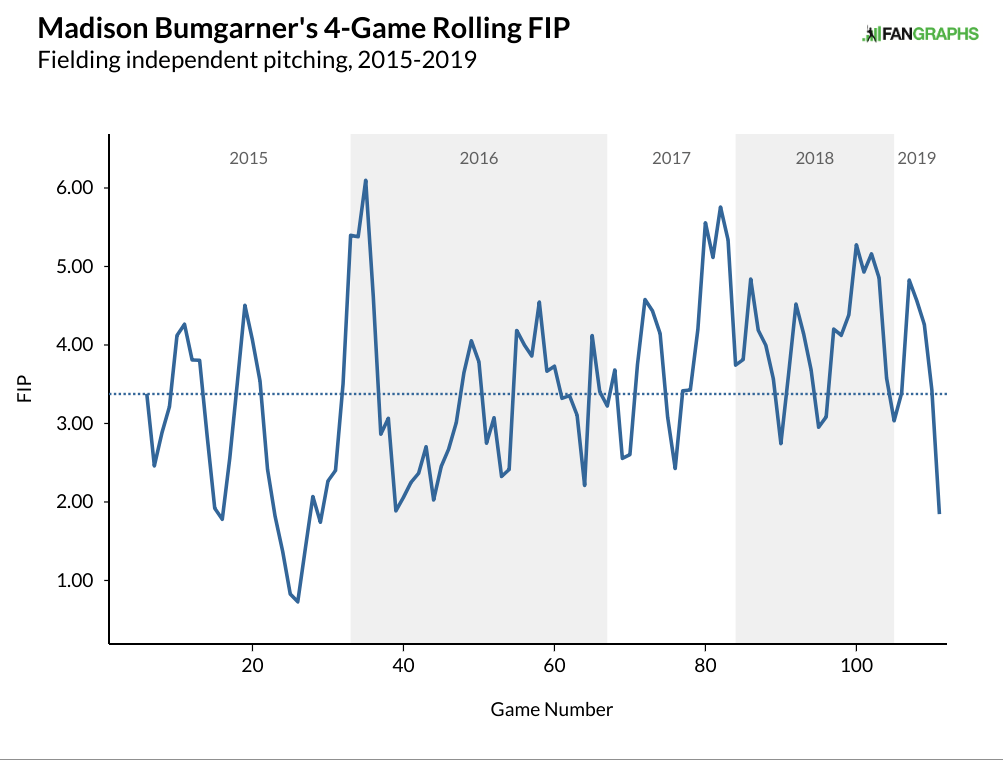

You can’t trade Bumgarner expecting the return you would for 2016-level Bumgarner, but you can get value from a team that could use a boost in a very competitive National League.

—

6. Mike Leake to the Cincinnati Reds for Robert Stephenson.

An innings-eater doesn’t have great value for the Mariners, who are unlikely to be very October-relevant. The Reds seem like they’ll happily volunteer to pick up the money to keep from trading a better prospect; they can’t put all their eggs into the 2019 basket.

With Alex Wood having back issues, a Leake reunion feels like a good match to me, and with Stephenson out of options, he’d get more time to hit his upside in Seattle than he would with a Reds team that really wants to compete this year.

—

7. Melvin Adon to the Washington Nationals for Yasel Antuna.

Washington keeps trading away highly interesting-yet-erratic relievers midseason in a scramble to find relief pitching. Why not acquire one of those guys for a change and see what happens? Stop being the team that ships out Felipe Vazquezes or Blake Treinens and be the team that finds and keeps them instead.

The Giants have a bit of a bullpen logjam and realistically, a reliever who can’t help them right now isn’t worth a great deal; relief is a high-leverage role and by the time Adon is ready, the Giants will likely be a poor enough team that it won’t matter. They may already be! Antuna gives them a lottery pick for a player who could help the team someday in a more meaningful way.