For the 18th consecutive season, the ZiPS projection system is unleashing a full set of prognostications. For more information on the ZiPS projections, please consult this year’s introduction and MLB’s glossary entry. The team order is selected by lot, and the next team up is the Kansas City Royals.

Batters

Coming into the 2021 season, there were reasons to be optimistic about the future of Kansas City’s offense, with Bobby Witt Jr., MJ Melendez, Nick Pratto, and Vinnie Pasquantino. Three of these four played well in the majors, but only one — and probably the one the Royals were themselves least high on, Pasquantino — really wowed offensively. Witt was solid, but far from amazing, and Melendez’s bat was mainly good because he plays a position that he may not be playing for very long. I guess what it comes down to is a simple question: outside of Pasquantino, who do you feel better about now than a year ago? The problem with the Royals is that I’m hard-pressed to give many names in response to that question.

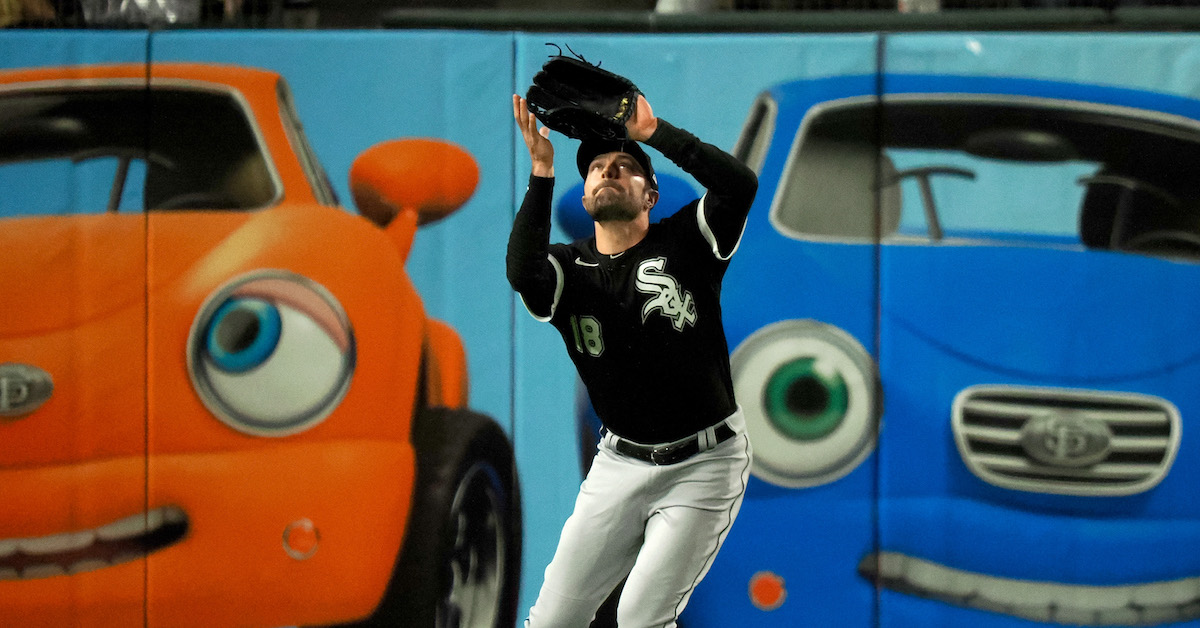

KC’s minor league hitters didn’t come roaring out of the gate, which makes the challenges steeper for the next front office/manager. It’d be easy if Melendez had pushed Salvador Perez to permanent DH status or if Pratto blew everyone away at first, but neither really happened, so decisions have to be made. Except for Michael A. Taylor, the legacy veterans are pretty much gone, and while Taylor is frequently named as a possible trade candidate, if he were a car, he’s in a situation similar to that of a 1999 Ford Taurus: you’ll probably find a new home for him, but not someone who is going to offer much in return.

Can Pratto hit at the major league level? After all, he didn’t really hit at the minor league level in 2022. Can Melendez play catcher successfully? Is Witt a shortstop? The Royals have to answer these questions, and if they don’t make great strides into doing that in 2023, the season is probably a failure overall. At least they’ve moved on from Ryan O’Hearn. They’ll need to; of hitters yet to make their major league debut, ZiPS only sees Maikel Garcia as having a strong chance at a 10-WAR career. Read the rest of this entry »