A year ago, Chris Sale and Clayton Kershaw took the mound in the opening game of the World Series. As far as pitching matchups go, those names might have made for the greatest Game 1 of all time. Sale was coming off another great season, with a FIP and ERA both around two, having amassed roughly 14 WAR over the previous two seasons combined. Kershaw has been the most dominating pitcher of his era, winning three Cy Young Awards with another three top-three finishes plus an MVP. Of course, that version of Kershaw wasn’t pitching last season, dimming the true battle of aces wattage and putting it more in the middle tier of World Series opener pitching matchups. That’s not the case tonight, as Gerrit Cole and Max Scherzer make for what is arguably the greatest Game 1 pitching matchup in World Series history.

Max Scherzer has won two of the last three Cy Young awards and finished in second place last season. He was a favorite for the award in the first half as his 5.7 WAR essentially lapped the field, but injury trouble forced him to take some time off and he wasn’t as sharp on return. He still finished the season with a 35% strikeout rate, a 5% walk rate, a 2.92 ERA, 2.45 FIP, and 6.5 WAR, the last of which was second to only Jacob deGrom in the NL and fourth in baseball behind Gerrit Cole and Lance Lynn. Scherzer has begun to shrug off the late-season donwturn and in the last two rounds of the playoffs, he has pitched 15 innings, struck out 21, walked just five and given up just a single run. His velocity has trended up in the postseason and he’s pitching with eight days rest.

As for Gerrit Cole, he topped all pitchers with 7.4 WAR this season; since the start of 2018, only deGrom and Scherzer have more than Cole’s 13.4 WAR. He’s returned to ace status after a great 2015 season, with injuries slowing him down in 2016 and ’17. He deserves to win the Cy Young award as he heads to free agency, and he has had a brilliant postseason up to this point with 22.2 innings, 32 strikeouts, and just one run in three starts. We have arguably the best pitcher in baseball right now going up against the best pitcher in baseball over the last three (and maybe up to eight) years.

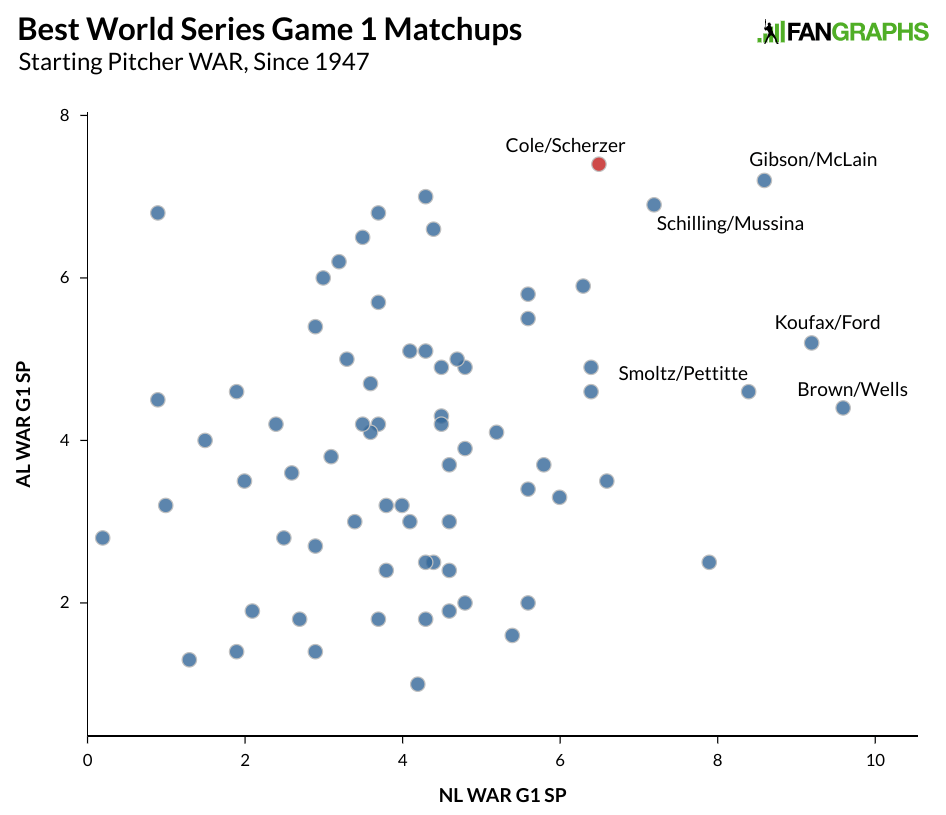

Looking only at single-season WAR, the duo is impressive for the first game of the World Series. Look at the scatter plot below, which shows all matchups for World Series openers since 1947:

Cole has the highest WAR for an American League starter in Game 1 of the World Series since at least 1947. Before that, Smoky Joe Wood put up 7.6 WAR for the Red Sox in 1912, while Lefty Grove had 8.3 WAR for the A’s in 1930, and Hal Newhouser’s 8.2 WAR paced the Tigers in 1945. Those are the only pitchers with better seasons in the American League to start Game 1 of the World Series. Scherzer’s 6.5 WAR ranks eighth among the 72 NL Game 1 starting pitchers since 1947. On average, or using geometric mean to avoid one really good starting pitcher skewing the matchup, tonight’s game is very close to the top, but not quite the best:

Best World Series Game 1 Matchups

The Year of the Pitcher back in 1968 wasn’t just some clever name. It really was a year of incredible pitching. Nobody doubts Gibson’s greatness. He averaged more than 5 WAR per season before 1968 and then put up another 18.6 WAR in the two seasons following that historic 1968 campaign. Denny McLain, on the other hand, had put up a total of two wins the previous two seasons, and after a seven-win 1969 season was replacement level as a gambling suspension and arm trouble caused his lackluster rest-of-career.

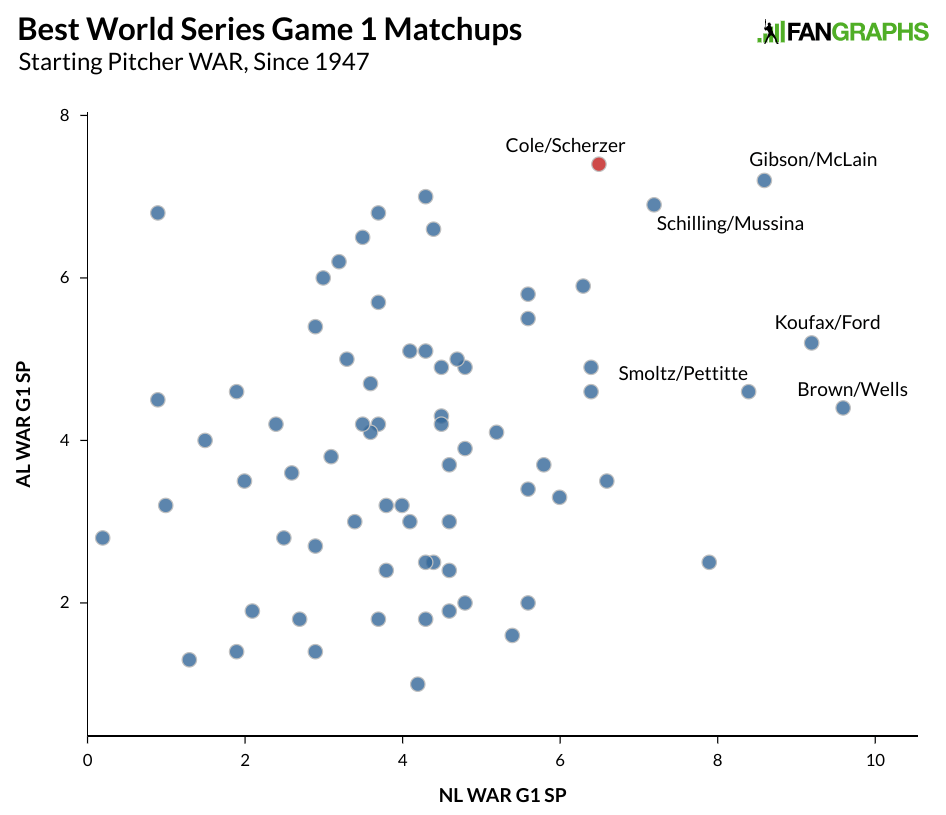

As for the second-highest matchup, Schilling hadn’t been as good in his last few years with the Phillies but his time with the Diamondbacks coincided with a resurgence. Mussina’s 2001 season was the high point in a nine-year run that saw the Hall of Famer average 5.6 WAR per season. Just below Scherzer and Cole are Koufax and Ford, two Hall of Famers in the middle of their great careers. To provide some balance to the numbers above and find great seasons with some notion of staying power, I weighted the World Series season at 50% and the previous two seasons at 25% each:

Best World Series Game 1 Matchups

Since 1945

Tonight’s game narrowly edges the Koufax-Ford matchup from 1963 as well as the Cliff Lee-Tim Lincecum battle, as the latter was coming off back-to-back Cy Youngs in 2008 and 2009 before a solid 2010 season. If in-season WAR is the sole determining factor in the matchup, then the Gibson-McLain battle is still number one with Schilling and Mussina in 2001 second, and tonight’s game coming in third. If you want to consider what happened in-season most, but provide a little more weight to fairly recent performances, there hasn’t been a better Game 1 matchup in at least 70 years.