The Art, Science, and Psychology of Catcher Framing

Catching is a thankless job, but it’s widely considered to be one of the most important roles on the field. In 2018, there were 721,191 pitches thrown in the major leagues, and there was a catcher on the receiving end of all of them. Of those pitches, umpires got the ball or strike call wrong nearly 5% of the time. Every umpire has quantifiable tendencies, some of which adjust from pitcher to pitcher and some of which remain consistent. Nearly all umpiring careers follow a trajectory similar to that of players, in that they start in the minor leagues and work to be promoted, calling balls and strikes in front of TrackMan arrays, often for years.

As such, the sample of data teams can use to detect those tendencies grows quickly. The more pitches called, the more data teams collect, meaning that by the time umpires reach the upper levels of the minor leagues, their tendencies are a known commodity. And while umpires can and certainly do improve their craft, old habits are tough to kick. In March, building on previous research, FanGraphs released an update to our catcher WAR that includes the value of pitch framing. Which catchers generate more called strikes for their pitchers can be quantified, but the question remains: How can catchers improve their receiving abilities?

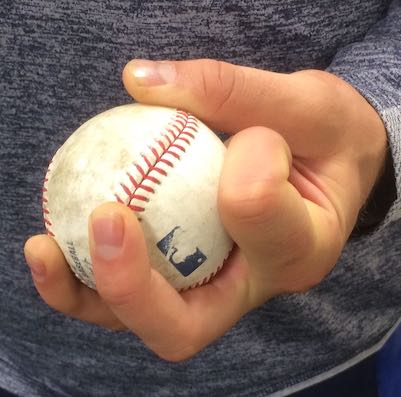

To start, it’s probably better to think of it not as pitch “framing,” but as pitch “absorption.” Consider the following. A baseball is about five ounces. That might not seem like much, but try to envision yourself catching an object that is moving in different directions and hitting different locations with the speed of a major league pitch and not only being able to keep still, but guide the ball in a motion that we call “framing” in order to make the pitch seem closer than it is. Of those 721,191 major league pitches thrown in 2018, 604,007 were “competitive” — more than 124 pitches per game, per team, that had a chance to be called a strike. Read the rest of this entry »

Dan Szymborski

Dan Szymborski