JAWS and the 2026 Hall of Fame Ballot: Howie Kendrick

The following article is part of Jay Jaffe’s ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2026 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to this year’s ballot, and other candidates in the series, use the tool above; an introduction to JAWS can be found here. For a tentative schedule, see here. All WAR figures refer to the Baseball Reference version unless otherwise indicated.

| Player | Pos | Career WAR | Peak WAR | JAWS | H | HR | SB | AVG/OBP/SLG | OPS+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Howie Kendrick | 2B | 35.0 | 25.6 | 30.3 | 1,747 | 127 | 126 | .294/.337/.430 | 109 |

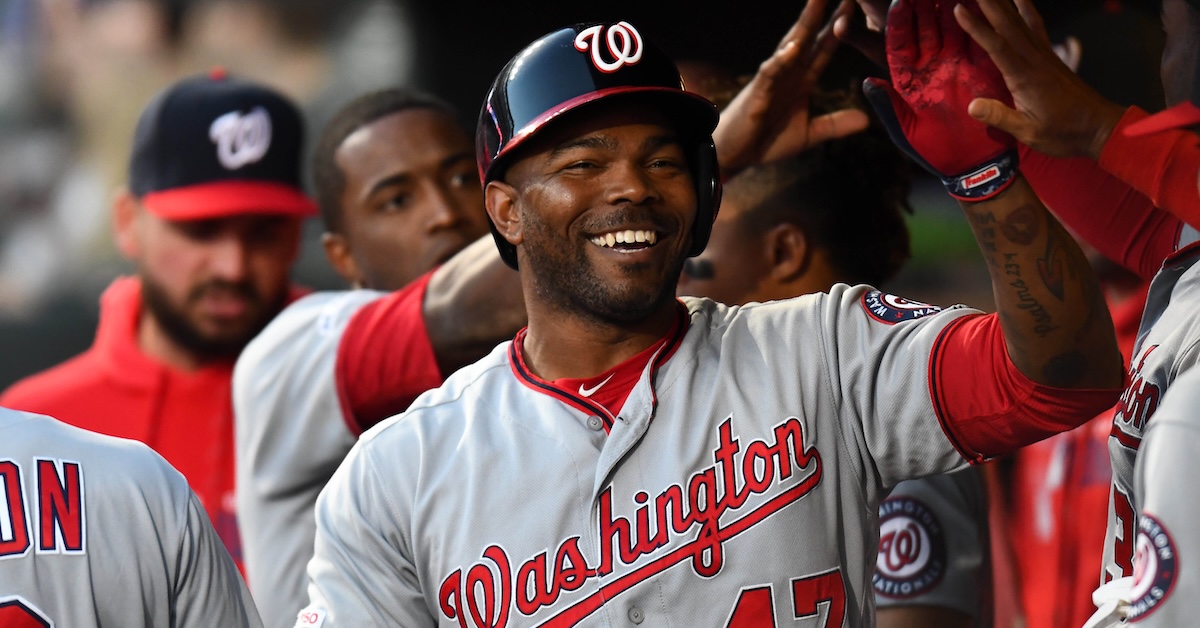

In their backyard baseball fantasies and daydreams, what kid hasn’t imagined hitting a late-inning home run to win a playoff game, or even Game 7 of the World Series? Howie Kendrick lived that dream not once but twice during the 2019 postseason, capped by a homer that sent the Washington Nationals on their way to their first championship in franchise history. What’s more, his October run (which also included NLCS MVP honors) topped off a storybook rise from humble beginnings that included a complicated family situation growing up and an amateur career that took place in almost complete obscurity.

“The more I learned about him, he starts telling me about how no schools wanted him, how it was really hard to stay confident,” former Angels teammate Torii Hunter, who mentored Kendrick upon joining the Angels in 2008, recalled in ’19. “I just kept thinking: This guy could have really fallen through the cracks.”

What put Kendrick on the map was his legendary bat-to-ball ability. Though he never won the major league batting title that was expected of him while hitting for a .358 average during his time in the minors, he carved out an impressive 14-year career, earning All-Star honors and helping his teams make the playoffs eight times.

…

Howard Joseph Kendrick III was born on July 12, 1983 in Jacksonville, Florida. He never knew his father, and because his mother, Belinda Kendrick, was a staff sergeant serving overseas in the United States Army, he and his two sisters grew up in the care of his maternal grandmother, Ruth Woods, in Callahan, Florida, a two-stoplight town of less than 1,000 people near the Georgia border. All 12 of Woods’ children, and their children, lived in the area as well.

From the time he was five, Kendrick loved to hit. He and his sisters and cousins would play a game called Strikeout using a broom handle and the spiky, gum ball-sized burrs that fell from the tree in his grandmother’s backyard. “One kid hit, and the others pitched the burrs or fielded. Whiff or hit a pop-up that was caught (the downward arc of the burr slowed by the looming branches above), and the next hitter was up,” wrote Sports Illustrated’s Chris Ballard in a 2008 profile.

“We couldn’t strike him out,” younger sister Michelle told Ballard. “Sometimes he’d be up there hitting for 20 or 30 minutes. Usually, I’d just quit.”

When Woods tired of her grandson breaking windows by hitting pebbles and other objects, she signed him up for T-ball. Kendrick fell in love with the game and became a Braves fan; his favorite players were David Justice and John Smoltz, but he also admired footage of Henry Aaron’s smooth swing.

When Kendrick was 12, his mother returned from overseas duty, but home life proved so problematic that he moved in with friends. “As I got older, things with my mom, we didn’t get along very well,” he told the Riverside Press-Enterprise in 2007. “Things happened, and I just moved in with (the Cokers). There’s differences now where I look back, and it’s like it was adolescent things. I was hard-headed and wanted to think I knew everything, and she was actually right in a lot of things she was trying to tell me.”

Kendrick loved baseball so much that he passed up opportunities to play football, basketball, and soccer at West Nassau High School. Just 5-foot-7 and 110 pounds, and unable to afford to play travel ball, he struggled to get noticed, receiving no scholarship offers. Varsity baseball coach Richard Pearce tried to drum up interest from recruiters. “I traveled the country trying to find anyone who would listen,” he told the Washington Post’s Jesse Dougherty in 2019. “But they didn’t want the little guy.”

After trying out for eight junior college programs to no avail, Kendrick got a late scholarship offer from St. Johns River, a community college in northeast Florida. He played just one season there, but he earned Conference Player of the Year honors, and caught the eye of Brevard Community College coach Ernie Rosseau, who in turn tipped off Tom Kotchman, the legendary Angels scout, to come see him. Kotchman was captivated by Kendrick’s batting practice session. “My goodness, the kid hit the ball. I couldn’t believe there weren’t other scouts there,” he told Ballard. “And other JCs cut this guy? What were they thinking?”

Kotchman did his best to downplay his interest in this sleeper from the sticks, lest other teams catch on. None did; the Angels drafted Kendrick in the 10th round in 2002, originally intending for him to be a draft-and-follow, though at Kotchman’s behest, they quickly signed him for a $100,000 bonus. He was so raw that he hadn’t been taught basic defensive fundamentals such as how to cover bunts or execute rundowns until he reached the minors. But he could hit, and he did: .318/.368/.408 with 12 steals in 42 games for the Angels’ Arizona League affiliate in 2002, and then .368/.434/.517 with three homers and eight steals at Rookie-Level Provo in ’03; he overcame a 4-for-40 start that year and hit above .400 in back-to-back months.

Though he missed two months of the 2004 season at A-level Cedar Rapids, Kendrick hit .367/.398/.578 with 10 homers and 12 steals in 75 games. He was 41 plate appearances short of qualifying for the Midwest League batting title but won it anyway via the phantom at-bat rule (he would still have led even if he’d gone 0-for-41). He continued to rake in 2005, hitting .367/.406/.614 with 19 homers and 25 steals split between High-A Rancho Cucamonga and Double-A Arkansas, and turned heads in the Arizona Fall League as well. Baseball America ranked Kendrick (then listed at 5-foot-10, 180 pounds) 12th on its Top 100 Prospects list in the spring of 2006 — it would be 10 years before they’d place another second baseman anywhere on their list — and saddled him with the prediction that would become his calling card (emphasis added):

His swing is compact, balanced and easily repeated. He lets pitches get deep before centering them and driving them to all fields. His swing doesn’t create much loft, but he should hit at least 15-20 homers annually because of his bat speed and penchant for making hard contact… Kendrick’s non-hitting tools aren’t special. He has fringe-average speed, and his range, arm and defensive footwork are average at best. He makes contact so easily that he rarely walks. Kendrick could win multiple batting titles in the big leagues.

After a hot start at Triple-A Salt Lake City — where he hit an absurd .369/.408/.631 in 69 games — Kendrick was called up to the Angels. He went 0-for-4 in his major league debut against the Tigers on April 26, 2006, but singled off the A’s Barry Zito for his first hit in his next game, on May 1. The Angels optioned him back to Salt Lake City in mid-May after a 3-for-26 start, but he returned following the All-Star break, mashing two doubles while going 3-for-4 and driving in the winning run on July 16 against the Devil Rays. Ten days later, he hit his first homer, off Devil Rays pitcher Shawn Camp. With Adam Kennedy entrenched at second base but rookie first baseman Kendrys Morales slumping his way towards a demotion, Kendrick took over the latter position without any previous professional experience, starting 42 of the team’s final 63 games there while occasionally spotting at the keystone. He hit .285/.314/.416 (87 OPS+) with four homers, six steals, and above-average defense en route to 1.5 WAR, though his 3.2% walk rate was cause for concern.

The following spring, the Baseball Prospectus 2007 annual repeated the batting title prediction for the first of seven times over the next decade (never doubt the BP staff’s commitment to a bit): “A bumpy transition to the majors might have dulled some of the anticipation, but make no mistake about it — there are batting titles in Kendrick’s bat.” With Kennedy having departed in free agency, Kendrick claimed the second base job and hit .322/.347/.450 (108 OPS+) with five homers and 2.5 WAR, albeit in just 88 games. His batting average would have cracked the American League’s top 10 had he not missed 11 weeks due to separate fractures of two fingers on his left hand, one via a hit-by-pitch, the other while swinging.

Kendrick performed similarly (.306/.333/.421, 97 OPS+, 1.9 WAR) in 2008 despite missing another 10 weeks due to a recurrent left hamstring strain. Despite a slow start that led to a three-week stint back in Triple-A, he showed more power in 2009 (.291/.334/.444, 10 homers, 104 OPS+, 3.1 WAR), though upon returning to the majors, he wound up platooning with Maicer Izturis, starting 29 of the team’s final 31 games against lefties but just 11 out of 52 against righties within that span. Under manager Mike Scioscia, the Angels won the AL West annually from 2007–09; they took early exits at the hands of the Red Sox in the first two of those seasons while Kendrick went a combined 4-for-27, but swept Boston in the 2009 Division Series while Kendrick made just five plate appearances. He started four games in the 2009 ALCS against the Yankees, coming up big in Game 3 by going 3-for-5 with a solo homer off Andy Pettitte, a triple off Joba Chamberlain, and a two-out, 11th-inning single off Alfredo Aceves, scoring the winning run two pitches later on a double by Jeff Mathis. He went hitless in his final two appearances as the Yankees prevailed in six games.

Though Kendrick was healthy enough to play 158 games in 2010, the hits didn’t fall, as his batting average on balls in play dropped from .338 to a career-low .313; he hit an underwhelming .279/.313/.407 (99 OPS+). He nearly doubled his WAR from 2010 (2.4) to ’11 (4.6 WAR) while homering a career-high 18 times, batting .285/.338/.464 (126 OPS+) and making his lone All-Star team. That performance helped him net a four-year, $33.5 million extension in January 2012, one that included limited no-trade protection.

Kendrick hit a combined .292/.336/.410 (113 OPS+) over the next three seasons while averaging nine homers and 11 steals. He totaled 6.5 WAR in 2012–13, then posted career bests in DRS (13) and WAR (6.1) in ’14. Led by Mike Trout in his first MVP-winning season, the Angels won a major league-high 98 games and returned to the playoffs after a four-year drought, but face-planted in the Division Series yet again; Kendrick went 2-for-13 in a sweep by the Royals.

In December 2014, as part of new Dodgers president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman’s whirlwind of interlocking trades, Kendrick was sent 30 miles up Interstate 5 in exchange for pitching prospect Andrew Heaney, whom the Dodgers had just acquired from the Marlins in a seven-player deal that sent All-Star second baseman Dee Strange-Gordon to Miami. Taking over at second base, Kendrick hit about as well as in 2014 (.295/.336/.409, 108 wRC+), but missed time due to a left calf strain, slipping to -8 DRS and 1.6 WAR. The Dodgers won the NL West despite getting just 2.4 WAR from their starting middle infield of Kendrick and fellow winter acquisition Jimmy Rollins, down from 7.2 the year before with Strange-Gordon and Hanley Ramirez. Kendrick went 6-for-22 during the Dodgers’ loss to the Mets in a five-game Division Series, but his biggest hit, a three-run ninth-inning homer in Game 3, came when the team trailed by nine runs.

The Dodgers treated Kendrick’s subpar season as an aberration, re-signing him to a two-year, $20 million deal when he hit free agency. His return didn’t go well, as he had his worst-ever season at the plate (.255/.326/.366, 87 OPS+), and became a significant a drag on the offense because the Dodgers used him mostly in left field, with occasional infield duties sprinkled in; though he held his own defensively at the new positions (including third base), he produced just 0.8 WAR. Used off the bench more often than as a starter during the postseason, he went 5-for-22 with a pair of doubles in the Division Series against the Nationals and the NLCS against the Cubs.

In November, the Dodgers shipped Kendrick to Philadelphia in exchange for Darin Ruf and Darnell Sweeney, neither of whom would ever play a game for Los Angeles. Kendrick was at a low point. “I was just down on the game,” he told The Athletic’s Brittany Ghiroli in 2019. “I was at a point in my career where I didn’t enjoy playing.”

Splitting time between left field and second base, and missing over two months due to abdominal and hamstring strains, Kendrick played just 39 games for the Phillies, but went on a heater driven by a .418 BABIP, hitting .340/.397/.454. Even on a team headed for 96 losses, the now-33-year-old found that he enjoyed mentoring younger players. More from Ghiroli:

“I was never really seen as that veteran guy, but when I got [to Philly], my role switched,” Kendrick said. “All the young guys would talk to me, ask me about stuff. It was funny; I fell in love with the game and playing the game again when I was there because it was so fun being able to talk to the guys and watch them get better.”

On June 18, Kendrick recorded the 1,500th hit of his career, a single off the Diamondbacks’ Robbie Ray. On July 28, the Phillies traded Kendrick and about $1.6 million to the Nationals in exchange for pitching prospect McKenzie Mills and international bonus slot money. Kendrick continued to hit well while mainly covering left field in the absence of the injured Jayson Werth. Werth’s return limited Kendrick to pinch-hitting and defensive replacement duty as the Nationals went three-and-out in the Division Series against the Cubs.

Still, the Nationals valued Kendrick enough to re-sign him to a two-year, $7 million deal. Over the winter, he worked with hitting coach Kevin Long to emphasize driving the ball, and pulling it with greater frequency. With his launch angle above two degrees (!) for the first time in the Statcast era (7.9 degrees), he started the 2018 season well, but on May 19, playing his 40th game of the season, he ruptured his right Achilles tendon while running down a fly ball. The injury required season-ending surgery, but Kendrick’s rehab helped him get into better shape. Though he missed the first week of the 2019 season recovering from a left hamstring strain, he posted a career-best offensive season, batting a sizzling .344/.395/.572 (146 OPS+) with 17 homers in 370 plate appearances as manager Dave Martinez was mindful of not overtaxing him. He made 35 starts at first base, 18 at second, 10 at third base, and seven at DH; he also hit .361/.415/.611 with two homers in 41 plate appearances as a pinch-hitter.

After winning 93 games, the Nationals beat the Brewers in the Wild Card Game, upset the reigning National League champion Dodgers in a five-game Division Series, swept the Cardinals in the NLCS, and overcame a three-games-to-two deficit to win the World Series against the Astros in Houston. Kendrick was a modest 5-for-18 from the Wild Card Game through the first four games against the Dodgers. Los Angeles led Washington 3-1 heading into the top of the eighth when Anthony Rendon and Juan Soto clubbed back-to-back home runs off a flagging Clayton Kershaw, tying the game. The tie held until the top of the 10th, when Joe Kelly loaded the bases with nobody out, then left a 97-mph fastball on the inner edge of the zone. Kendrick hit it 410 feet to center field for a stunning grand slam.

Kendrick went 5-for-15 in the NLCS, piling all his hits in Games 1 and 3. In the opener, he led off the second inning with a double off Miles Mikolas, then scored the game’s first run on a Yan Gomes double; his seventh-inning RBI single off John Brebbia extended the lead to 2-0, which proved to be enough. In Game 3, he went 3-for-4 with three doubles and three RBIs, highlighted by a two-run double off Jack Flaherty in the third inning, helping the Nationals open up a 4-0 lead in what ended up an 8-1 win. Though he went hitless in Game 4, the one-out intentional walk he was issued by Dakota Hudson contributed to a seven-run first inning, and after that, it was all over but the shouting.

In the World Series, Kendrick DHed for the four games in Houston, and started at second base in two of the three in Washington, going 7-for-25 in all. Through the first six games, his biggest contribution was in Game 2, when he went 2-for-5 with an RBI single off Ryan Pressley during the six-run rally in the seventh. In Game 7, the Nationals entered the seventh inning trailing 2-0, but Rendon’s one-out solo homer off Zack Greinke cut the lead in half, and when Soto drew a walk, Will Harris replaced Greinke. After getting strike one, Harris threw Kendrick a low-and-away cutter, and Kendrick sliced it down the right field line, off the foul pole for a two-run homer and a 3-2 lead. The Nationals added a run in the eighth and two in the ninth for a 6-2 win, claiming their first championship in franchise history.

A free agent again, Kendrick decided to continue playing, inking a one-year, $6.25 million deal with a mutual option for 2021. After the coronavirus pandemic delayed the start of the season, Kendrick hit a light .275/.320/.385 in 25 games while battling issues with his left hamstring. By the time he went on the injured list in early September, he estimated he could run at only 40–50% intensity, and he didn’t recover quickly enough to return. After considering his options, on December 21, 2020 he announced his retirement. “I feel as though I’d been a National my whole career and the wild, humbling and crazy ride we had in 2019 truly culminated everything I’d learned in my career, and we all became World Champions,” he wrote on Instagram. Less than a year later, he joined the Phillies front office as a special assistant to general manager Sam Fuld.

Kendrick never did win that batting title. A World Series ring and an indelible spot in the lore of a franchise that had never won it all before will have to do.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

Very underrated player but obviously not a hof but he had a moment that most players would kill for in the World Series.

Yeah, between that and $71 million in salary, I suspect any kid would be satisfied even if not going to make it to Cooperstown.