For the 22nd consecutive season, the ZiPS projection system is unleashing a full set of prognostications. For more information on the ZiPS projections, please consult this year’s introduction, as well as MLB’s glossary entry. The team order is selected by lot, and the next team up is the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Batters

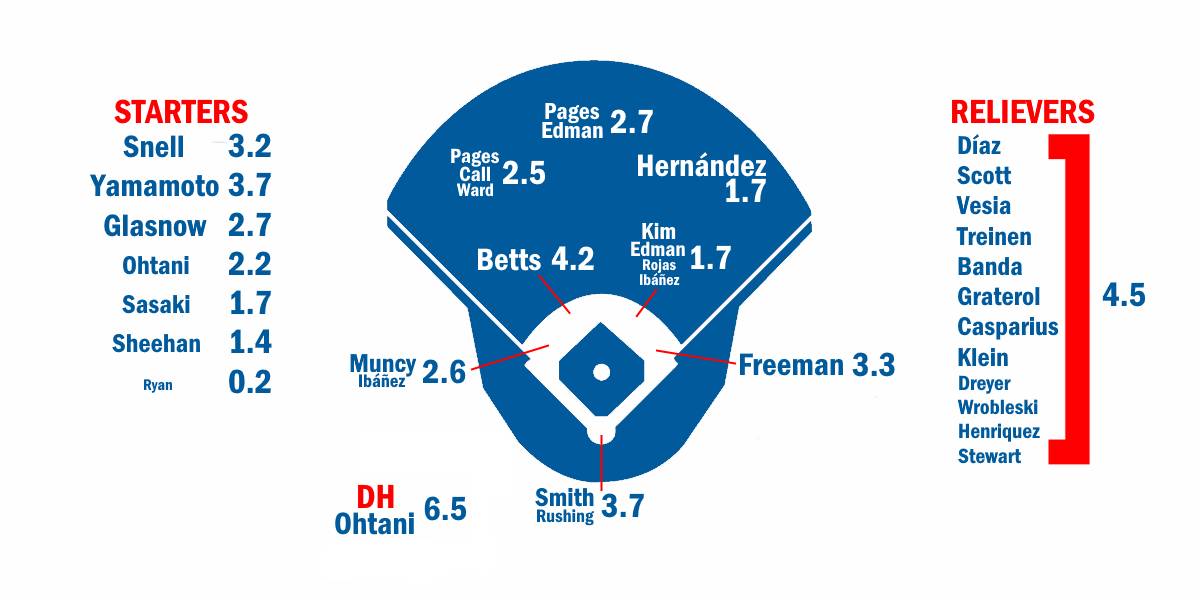

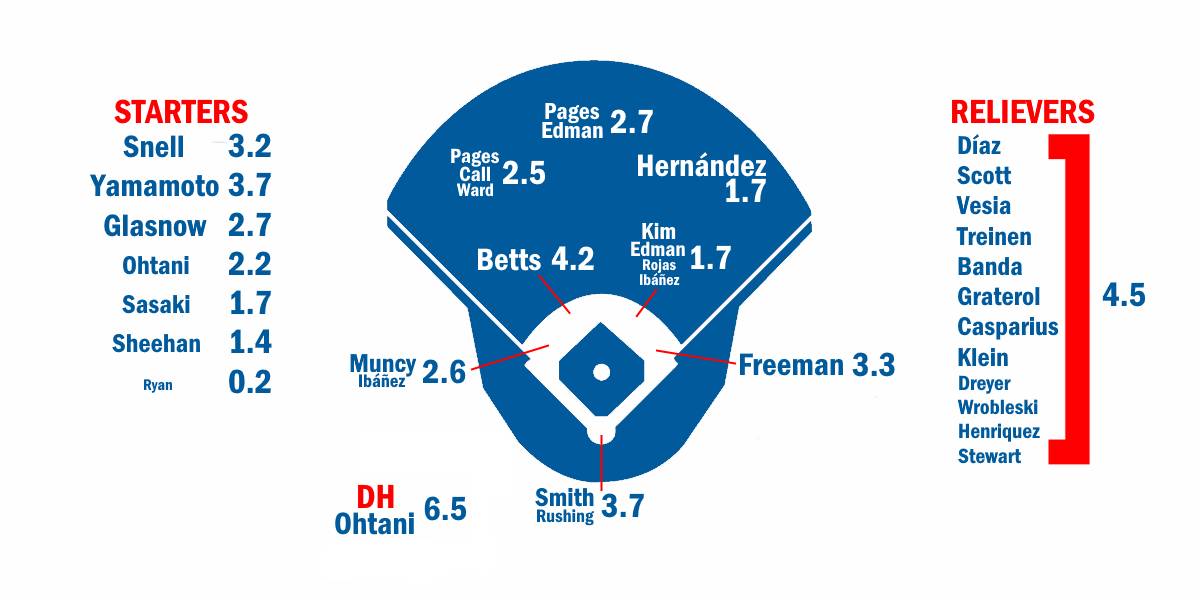

Yes, the Los Angeles Dodgers were an excellent team in 2025, a statement that won’t come as a shock to anyone who was paying even a quarter-attention to baseball last year. The team was adeptly built to weather any storms, navigated said metaphorical weather, and then enjoyed a rotation that was mostly healthy come October, a welcome reversal from their 2024 postseason squad. The Dodgers repeated as World Series champions — the first team in the 21st century to successfully defend a title — earning their third trophy of the 2020s. They’ll look to pull off the three-peat next, something that has only been done once in the last half century (the Yankees from 1998-2000). And they have relatively good odds to pull it off: For the fifth time in the last six years (the 2023 Atlanta Braves being the only exception), ZiPS sees the Dodgers as the best team in baseball.

With that, I’m basically done talking about how great the Dodgers are. After all, this isn’t just a great team, but an obviously great one. There’s no mystery to their greatness. They have three future Hall of Famers in the starting lineup (Shohei Ohtani, Freddie Freeman, and Mookie Betts), with a fourth player, Will Smith, who could very well emerge as one. The pitching staff is phenomenally talented, though it admittedly comes with its share of injury concerns. All of these marvelous players get marvelous projections; there honestly isn’t much new to say about them. So instead, I’m going to talk more about what the Dodgers are not, and what could end up being their undoing. Or at least, their undoing by their own lofty standards, which would still probably mean something like a 90-win season.

The Dodgers have a seemingly infinite supply of both cash and brainpower, which is a potent combination, especially for their NL West rivals. But they aren’t a juggernaut in the sense that they dominate games or even short series; the superteam storyline is something that’s been filched from sports with less randomness and awkwardly applied to baseball. There’s a bit of Baseball Calvinism at play, in the sense that because the Dodgers won the last two World Series, some seem to believe that they were always fated to do so. The truth is, like any baseball team, they weren’t truly dominant. They lost 43% of their games during the regular season. In 2022 and 2023, they didn’t even reach the NLCS. And despite getting all of their stars onto the field in the World Series, they still only narrowly bested the Blue Jays. That’s just how baseball works.

And while the lineup is certainly star-studded, there are some risks. The offense is mostly driven by the four guys I mentioned above, and all four are on the wrong side of 30. Freeman in particular showed some signs of aging in 2025, as both his out-of-zone swing rate and his whiff rate jumped, especially the latter, and he’s never had elite bat speed. By the end of this season, he’ll have celebrated his 37th birthday. Betts didn’t experience a huge WAR drop-off thanks to him playing better defense at shortstop than he had any right to, but he’s also coming off the worst offensive season of his big league career and is entering his mid-30s. Smith doesn’t have as many games on his knees as a lot of backstops his age, but the presence of Ohtani and Freeman also means that if he’s too banged up to play catcher, he can’t just slot in at first base or designated hitter to keep his bat in the lineup. Then there’s Ohtani, who’s so amazing that he can practically only surprise negatively at this point.

Outside of the top four, the Dodgers are good, but hardly as intimidating. Max Muncy seems to refuse to age, and the recently signed Andy Ibáñez can spell him against lefties as needed, but time remains undefeated and will likely come for the third baseman sooner than later. Elsewhere, the outfield is rather ordinary, as is second base. And if fortune doesn’t favor the Dodgers on the injury or aging front, the projections suggest that Josue De Paula and Zyhir Hope might not be ready to remedy the situation in the short-term, as ZiPS has both of their 2025 minor league translations with an OPS just shy of .650. The lesser prospects in the high minors don’t really fit the bill, either, as ZiPS likes the team’s fringy guys at Triple-A a lot less than it usually does.

Pitchers

As noted, this is a talented rotation, but as with the lineup, there is some downside risk that can’t be ignored. Yoshinobu Yamamoto was the only Dodger to pitch enough to qualify for the ERA title last year, and the only other pitchers who threw at least 100 innings are either retired (Clayton Kershaw) or in St. Louis (Dustin May). Now, if Los Angeles is able to line up Tyler Glasnow, Ohtani, Blake Snell, and Roki Sasaki in consecutive outings behind Yamamoto, opponents will be grateful that there are no five-game series during the regular season. But as we’ve seen in recent years, the Dodgers have struggled to get all their arms healthy at the same time, and there’s no Emperor of Sports Movie Endings to ensure that they’ll be able to do so come October.

That’s concerning for a few reasons, not least because while there’s obviously still more offseason to go, the Dodgers’ starting pitching depth is decidedly thinner than it has been in recent history. In the past, one of the reasons ZiPS has seen Los Angeles as having a very high floor is that it has usually liked the team’s no. 8-10 starters. But after Emmet Sheehan and his 4.13 projected ERA if he’s used as a starter full-time, ZiPS sees the Dodgers’ spare rotation candidates as a decidedly below-average lot. River Ryan, Kyle Hurt, Gavin Stone, Justin Wrobleski, and Landon Knack all have projected ERAs worse than 4.50 as starters.

After years spent shoring up their bullpen with cleverness, the Dodgers have taken an unusually direct approach the past two winters: giving a great reliever a whole bunch of money. Last offseason, it was Tanner Scott (it hasn’t gone well). This time around, it’s Edwin Díaz, who is an awesome reliever, even if he’s unlikely to reach the heights of his 2018 or 2022 seasons again. ZiPS is pretty happy with the rest of the bullpen, seeing Alex Vesia, Scott (in a bounce-back season), Jack Dreyer, and Wrobleski as all comfortably above average. (You can add in Brusdar Graterol, who also gets a solid projection after ZiPS takes his injury into account.) The computer is a bit more squeamish when it comes to Blake Treinen and Brock Stewart, but it still sees them as having really solid upside. This ought to be a good bullpen.

Even accounting for the potential downside scenarios, the Dodgers look like the best team in baseball. Now, this being baseball, they’re still more likely to end the season with a loss than a champagne shower, but they’re as well positioned to make a deep run as their fans could possibly hope.

Ballpark graphic courtesy Eephus League. Depth charts constructed by way of those listed here. Size of player names is very roughly proportional to Depth Chart playing time. The final team projections may differ considerably from our Depth Chart playing time.

Batters – Standard

| Player |

B |

Age |

PO |

PA |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

BB |

SO |

SB |

CS |

| Shohei Ohtani |

L |

31 |

DH |

696 |

592 |

138 |

171 |

30 |

5 |

52 |

138 |

95 |

166 |

29 |

5 |

| Mookie Betts |

R |

33 |

SS |

613 |

532 |

91 |

146 |

30 |

2 |

23 |

87 |

71 |

72 |

9 |

2 |

| Freddie Freeman |

L |

36 |

1B |

597 |

520 |

82 |

150 |

37 |

2 |

22 |

82 |

64 |

110 |

8 |

2 |

| Will Smith |

R |

31 |

C |

487 |

413 |

67 |

106 |

20 |

1 |

19 |

66 |

58 |

94 |

2 |

1 |

| Andy Pages |

R |

25 |

CF |

589 |

535 |

73 |

138 |

29 |

2 |

25 |

84 |

37 |

129 |

9 |

4 |

| Alex Freeland |

B |

24 |

SS |

591 |

514 |

77 |

119 |

26 |

1 |

19 |

71 |

65 |

159 |

14 |

4 |

| Dalton Rushing |

L |

25 |

C |

390 |

336 |

49 |

78 |

16 |

1 |

16 |

56 |

42 |

107 |

1 |

1 |

| Max Muncy |

L |

35 |

3B |

416 |

340 |

56 |

74 |

14 |

1 |

20 |

60 |

65 |

105 |

2 |

0 |

| Tommy Edman |

B |

31 |

2B |

414 |

379 |

56 |

95 |

18 |

2 |

13 |

50 |

27 |

73 |

10 |

1 |

| Alex Call |

R |

31 |

RF |

384 |

321 |

49 |

78 |

16 |

1 |

11 |

48 |

49 |

69 |

6 |

3 |

| Teoscar Hernández |

R |

33 |

RF |

563 |

518 |

71 |

138 |

27 |

1 |

28 |

92 |

35 |

149 |

6 |

2 |

| Ryan Ward |

L |

28 |

LF |

591 |

539 |

81 |

126 |

23 |

4 |

28 |

88 |

47 |

148 |

8 |

3 |

| Miguel Rojas |

R |

37 |

2B |

313 |

283 |

35 |

72 |

15 |

0 |

6 |

30 |

22 |

42 |

5 |

1 |

| Zach Ehrhard |

R |

23 |

RF |

529 |

468 |

70 |

107 |

24 |

1 |

15 |

70 |

46 |

116 |

18 |

3 |

| Andy Ibáñez |

R |

33 |

3B |

352 |

321 |

38 |

78 |

18 |

1 |

9 |

44 |

25 |

65 |

5 |

2 |

| Kole Myers |

L |

25 |

LF |

439 |

380 |

60 |

91 |

10 |

4 |

4 |

44 |

50 |

112 |

19 |

8 |

| Austin Gauthier |

R |

27 |

2B |

505 |

431 |

63 |

101 |

19 |

3 |

6 |

44 |

66 |

110 |

5 |

2 |

| Ryan Fitzgerald |

L |

32 |

SS |

355 |

317 |

38 |

71 |

16 |

2 |

11 |

47 |

30 |

94 |

4 |

3 |

| Kody Hoese |

R |

28 |

3B |

424 |

386 |

46 |

91 |

20 |

2 |

11 |

48 |

32 |

97 |

1 |

0 |

| Matt Gorski |

R |

28 |

LF |

361 |

335 |

48 |

76 |

15 |

2 |

18 |

67 |

20 |

113 |

8 |

4 |

| Chris Newell |

L |

25 |

CF |

518 |

461 |

59 |

95 |

20 |

2 |

21 |

66 |

49 |

192 |

13 |

3 |

| Michael Siani |

L |

26 |

CF |

458 |

406 |

53 |

83 |

12 |

3 |

6 |

38 |

40 |

126 |

19 |

5 |

| Eduardo Quintero |

R |

20 |

CF |

527 |

460 |

76 |

99 |

16 |

4 |

15 |

61 |

54 |

144 |

20 |

8 |

| Hyeseong Kim |

L |

27 |

2B |

356 |

334 |

39 |

79 |

14 |

3 |

7 |

46 |

15 |

104 |

22 |

2 |

| Michael Conforto |

L |

33 |

LF |

437 |

381 |

53 |

86 |

19 |

0 |

17 |

53 |

46 |

108 |

1 |

0 |

| Elijah Hainline |

R |

23 |

SS |

467 |

406 |

57 |

82 |

17 |

2 |

8 |

48 |

50 |

134 |

13 |

5 |

| James Tibbs III |

L |

23 |

RF |

544 |

474 |

68 |

101 |

16 |

3 |

18 |

72 |

59 |

142 |

5 |

3 |

| Josue De Paula |

L |

21 |

LF |

479 |

417 |

58 |

92 |

15 |

1 |

13 |

51 |

57 |

117 |

15 |

4 |

| Nelson Quiroz |

L |

24 |

C |

209 |

195 |

20 |

50 |

8 |

1 |

2 |

18 |

12 |

21 |

0 |

0 |

| CJ Alexander |

L |

29 |

1B |

435 |

401 |

51 |

89 |

20 |

3 |

15 |

57 |

30 |

130 |

4 |

3 |

| Taylor Young |

R |

27 |

2B |

537 |

476 |

60 |

103 |

21 |

2 |

3 |

43 |

51 |

119 |

24 |

6 |

| Chuckie Robinson |

R |

31 |

C |

315 |

291 |

31 |

64 |

8 |

1 |

6 |

33 |

17 |

86 |

1 |

1 |

| Chris Okey |

R |

31 |

C |

180 |

168 |

17 |

37 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

18 |

8 |

49 |

1 |

0 |

| Griffin Lockwood-Powell |

R |

28 |

C |

363 |

323 |

34 |

67 |

13 |

1 |

8 |

35 |

35 |

94 |

0 |

0 |

| Logan Wagner |

B |

22 |

3B |

516 |

451 |

67 |

83 |

15 |

2 |

12 |

55 |

51 |

162 |

8 |

2 |

| Noah Miller |

B |

23 |

SS |

496 |

462 |

52 |

101 |

17 |

2 |

6 |

43 |

28 |

103 |

3 |

1 |

| Carlos Rojas |

R |

23 |

C |

261 |

236 |

20 |

50 |

8 |

0 |

2 |

20 |

16 |

45 |

0 |

0 |

| Nick Senzel |

R |

31 |

3B |

383 |

345 |

43 |

77 |

14 |

1 |

10 |

45 |

32 |

83 |

5 |

2 |

| Enrique Hernández |

R |

34 |

3B |

352 |

320 |

41 |

70 |

15 |

0 |

10 |

41 |

26 |

83 |

1 |

1 |

| Frank Rodriguez |

R |

24 |

C |

191 |

174 |

19 |

33 |

7 |

0 |

3 |

16 |

12 |

50 |

0 |

0 |

| Jake Gelof |

R |

24 |

3B |

375 |

339 |

48 |

61 |

16 |

1 |

11 |

43 |

32 |

122 |

5 |

4 |

| Kendall George |

L |

21 |

CF |

513 |

455 |

76 |

108 |

7 |

5 |

3 |

38 |

52 |

103 |

43 |

15 |

| Kendall Simmons |

R |

26 |

3B |

233 |

214 |

22 |

42 |

9 |

1 |

6 |

28 |

13 |

75 |

2 |

1 |

| Zyhir Hope |

L |

21 |

RF |

524 |

469 |

60 |

98 |

21 |

2 |

12 |

58 |

50 |

160 |

13 |

4 |

| Ezequiel Pagan |

L |

25 |

RF |

363 |

338 |

35 |

80 |

12 |

2 |

7 |

41 |

16 |

73 |

5 |

4 |

| Mike Sirota |

R |

23 |

CF |

284 |

247 |

42 |

51 |

10 |

1 |

8 |

38 |

32 |

77 |

2 |

3 |

| Damon Keith |

R |

26 |

RF |

402 |

365 |

45 |

79 |

16 |

2 |

12 |

46 |

31 |

143 |

5 |

4 |

| Kyle Nevin |

R |

24 |

3B |

383 |

351 |

42 |

80 |

14 |

3 |

8 |

38 |

26 |

117 |

6 |

2 |

| Trei Cruz |

L |

25 |

3B |

340 |

311 |

31 |

61 |

11 |

1 |

10 |

41 |

23 |

90 |

3 |

2 |

| Eliezer Alfonzo |

B |

26 |

C |

331 |

311 |

33 |

70 |

11 |

0 |

5 |

36 |

15 |

39 |

0 |

1 |

| Yeiner Fernandez |

R |

23 |

C |

446 |

405 |

44 |

93 |

16 |

1 |

3 |

39 |

30 |

63 |

2 |

2 |

| Cameron Decker |

R |

22 |

1B |

299 |

266 |

31 |

46 |

12 |

1 |

10 |

38 |

24 |

112 |

1 |

2 |

| Jordan Thompson |

R |

24 |

SS |

409 |

374 |

40 |

73 |

15 |

0 |

9 |

43 |

24 |

133 |

6 |

5 |

| Wilman Diaz |

R |

22 |

2B |

321 |

294 |

33 |

60 |

12 |

3 |

4 |

28 |

20 |

111 |

6 |

4 |

| Sean McLain |

R |

25 |

SS |

430 |

386 |

43 |

71 |

13 |

2 |

5 |

37 |

32 |

122 |

5 |

4 |

| Eduardo Guerrero |

B |

21 |

SS |

395 |

341 |

38 |

66 |

7 |

3 |

2 |

27 |

42 |

87 |

4 |

3 |

| Joe Vetrano |

L |

24 |

1B |

404 |

371 |

38 |

75 |

14 |

3 |

8 |

39 |

30 |

131 |

9 |

3 |

| Samuel Munoz |

L |

21 |

LF |

515 |

465 |

53 |

93 |

16 |

4 |

12 |

49 |

42 |

139 |

9 |

4 |

| Mairoshendrick Martinus |

R |

21 |

SS |

405 |

373 |

46 |

70 |

13 |

2 |

8 |

37 |

24 |

142 |

9 |

4 |

| John Rhodes |

R |

25 |

1B |

438 |

397 |

38 |

74 |

15 |

1 |

8 |

41 |

35 |

128 |

5 |

1 |

| Bubba Alleyne |

B |

27 |

2B |

314 |

291 |

29 |

51 |

9 |

2 |

4 |

26 |

16 |

97 |

10 |

3 |

| Jackson Nicklaus |

L |

23 |

1B |

309 |

274 |

31 |

40 |

8 |

1 |

6 |

26 |

32 |

154 |

0 |

0 |

Batters – Advanced

| Player |

PA |

BA |

OBP |

SLG |

OPS+ |

ISO |

BABIP |

Def |

WAR |

wOBA |

3YOPS+ |

RC |

| Shohei Ohtani |

696 |

.289 |

.389 |

.620 |

178 |

.331 |

.318 |

0 |

6.6 |

.417 |

170 |

151 |

| Mookie Betts |

613 |

.274 |

.361 |

.468 |

131 |

.194 |

.281 |

-4 |

3.9 |

.357 |

125 |

93 |

| Freddie Freeman |

597 |

.288 |

.372 |

.494 |

141 |

.206 |

.330 |

-1 |

3.0 |

.369 |

131 |

98 |

| Will Smith |

487 |

.257 |

.355 |

.448 |

124 |

.191 |

.290 |

-1 |

3.0 |

.347 |

119 |

67 |

| Andy Pages |

589 |

.258 |

.315 |

.460 |

115 |

.202 |

.297 |

0 |

2.5 |

.333 |

118 |

81 |

| Alex Freeland |

591 |

.232 |

.325 |

.397 |

102 |

.165 |

.298 |

1 |

2.4 |

.318 |

106 |

71 |

| Dalton Rushing |

390 |

.232 |

.331 |

.429 |

112 |

.197 |

.291 |

-2 |

1.8 |

.331 |

115 |

48 |

| Max Muncy |

416 |

.218 |

.349 |

.441 |

121 |

.223 |

.251 |

-2 |

1.8 |

.343 |

112 |

53 |

| Tommy Edman |

414 |

.251 |

.305 |

.412 |

99 |

.161 |

.280 |

5 |

1.7 |

.311 |

96 |

50 |

| Alex Call |

384 |

.243 |

.353 |

.402 |

112 |

.159 |

.278 |

6 |

1.6 |

.334 |

107 |

48 |

| Teoscar Hernández |

563 |

.266 |

.318 |

.485 |

122 |

.219 |

.323 |

-3 |

1.6 |

.343 |

114 |

82 |

| Ryan Ward |

591 |

.234 |

.298 |

.447 |

106 |

.213 |

.270 |

6 |

1.5 |

.319 |

105 |

75 |

| Miguel Rojas |

313 |

.254 |

.313 |

.371 |

92 |

.117 |

.281 |

6 |

1.2 |

.301 |

86 |

34 |

| Zach Ehrhard |

529 |

.229 |

.307 |

.380 |

92 |

.151 |

.273 |

7 |

1.0 |

.302 |

97 |

59 |

| Andy Ibáñez |

352 |

.243 |

.304 |

.389 |

94 |

.146 |

.279 |

3 |

0.9 |

.303 |

88 |

40 |

| Kole Myers |

439 |

.239 |

.342 |

.318 |

88 |

.079 |

.330 |

9 |

0.9 |

.300 |

90 |

49 |

| Austin Gauthier |

505 |

.234 |

.341 |

.334 |

91 |

.100 |

.302 |

-3 |

0.8 |

.306 |

90 |

51 |

| Ryan Fitzgerald |

355 |

.224 |

.299 |

.391 |

93 |

.167 |

.283 |

-1 |

0.7 |

.302 |

87 |

39 |

| Kody Hoese |

424 |

.236 |

.297 |

.383 |

90 |

.148 |

.288 |

1 |

0.7 |

.297 |

88 |

44 |

| Matt Gorski |

361 |

.227 |

.269 |

.445 |

96 |

.218 |

.284 |

5 |

0.6 |

.304 |

96 |

43 |

| Chris Newell |

518 |

.206 |

.284 |

.395 |

89 |

.189 |

.298 |

-3 |

0.4 |

.294 |

97 |

56 |

| Michael Siani |

458 |

.204 |

.279 |

.293 |

62 |

.089 |

.281 |

7 |

0.4 |

.258 |

65 |

39 |

| Eduardo Quintero |

527 |

.215 |

.304 |

.365 |

88 |

.150 |

.279 |

-4 |

0.3 |

.295 |

96 |

58 |

| Hyeseong Kim |

356 |

.237 |

.277 |

.359 |

77 |

.122 |

.323 |

0 |

0.3 |

.278 |

75 |

38 |

| Michael Conforto |

437 |

.226 |

.318 |

.409 |

103 |

.183 |

.270 |

-3 |

0.3 |

.318 |

98 |

50 |

| Elijah Hainline |

467 |

.202 |

.299 |

.313 |

73 |

.111 |

.280 |

0 |

0.2 |

.277 |

79 |

43 |

| James Tibbs III |

544 |

.213 |

.306 |

.373 |

90 |

.160 |

.264 |

2 |

0.2 |

.300 |

96 |

56 |

| Josue De Paula |

479 |

.221 |

.319 |

.355 |

90 |

.134 |

.275 |

-2 |

0.0 |

.302 |

98 |

52 |

| Nelson Quiroz |

209 |

.256 |

.301 |

.338 |

80 |

.082 |

.279 |

-3 |

0.0 |

.283 |

80 |

20 |

| CJ Alexander |

435 |

.222 |

.278 |

.399 |

88 |

.177 |

.289 |

4 |

-0.1 |

.292 |

87 |

47 |

| Taylor Young |

537 |

.216 |

.302 |

.288 |

67 |

.072 |

.282 |

1 |

-0.1 |

.269 |

70 |

49 |

| Chuckie Robinson |

315 |

.220 |

.271 |

.316 |

65 |

.096 |

.291 |

1 |

-0.1 |

.260 |

65 |

26 |

| Chris Okey |

180 |

.220 |

.263 |

.315 |

62 |

.095 |

.293 |

-1 |

-0.2 |

.255 |

59 |

14 |

| Griffin Lockwood-Powell |

363 |

.207 |

.289 |

.328 |

74 |

.121 |

.267 |

-4 |

-0.2 |

.276 |

74 |

31 |

| Logan Wagner |

516 |

.184 |

.281 |

.306 |

65 |

.122 |

.256 |

4 |

-0.2 |

.266 |

72 |

41 |

| Noah Miller |

496 |

.219 |

.265 |

.303 |

60 |

.084 |

.269 |

6 |

-0.2 |

.251 |

64 |

38 |

| Carlos Rojas |

261 |

.212 |

.267 |

.271 |

52 |

.059 |

.254 |

2 |

-0.3 |

.243 |

56 |

17 |

| Nick Senzel |

383 |

.223 |

.295 |

.357 |

82 |

.134 |

.266 |

-5 |

-0.3 |

.287 |

78 |

38 |

| Enrique Hernández |

352 |

.219 |

.276 |

.359 |

77 |

.140 |

.264 |

-3 |

-0.4 |

.278 |

72 |

32 |

| Frank Rodriguez |

191 |

.190 |

.253 |

.282 |

50 |

.092 |

.248 |

0 |

-0.4 |

.240 |

54 |

12 |

| Jake Gelof |

375 |

.180 |

.251 |

.330 |

62 |

.150 |

.243 |

4 |

-0.4 |

.256 |

67 |

31 |

| Kendall George |

513 |

.237 |

.316 |

.295 |

74 |

.057 |

.301 |

-6 |

-0.5 |

.278 |

75 |

57 |

| Kendall Simmons |

233 |

.196 |

.258 |

.332 |

64 |

.136 |

.271 |

-2 |

-0.5 |

.260 |

68 |

19 |

| Zyhir Hope |

524 |

.209 |

.290 |

.339 |

77 |

.130 |

.290 |

3 |

-0.5 |

.280 |

85 |

50 |

| Ezequiel Pagan |

363 |

.237 |

.282 |

.346 |

76 |

.109 |

.283 |

2 |

-0.6 |

.276 |

80 |

36 |

| Mike Sirota |

284 |

.206 |

.299 |

.352 |

83 |

.146 |

.265 |

-7 |

-0.6 |

.289 |

89 |

28 |

| Damon Keith |

402 |

.216 |

.281 |

.370 |

81 |

.154 |

.319 |

-1 |

-0.7 |

.284 |

84 |

41 |

| Kyle Nevin |

383 |

.228 |

.285 |

.353 |

78 |

.125 |

.319 |

-7 |

-0.7 |

.280 |

81 |

37 |

| Trei Cruz |

340 |

.196 |

.256 |

.334 |

65 |

.138 |

.242 |

-1 |

-0.8 |

.259 |

69 |

28 |

| Eliezer Alfonzo |

331 |

.225 |

.264 |

.309 |

61 |

.084 |

.243 |

-4 |

-0.8 |

.251 |

66 |

26 |

| Yeiner Fernandez |

446 |

.230 |

.294 |

.296 |

67 |

.066 |

.265 |

-9 |

-1.0 |

.265 |

69 |

36 |

| Cameron Decker |

299 |

.173 |

.254 |

.338 |

65 |

.165 |

.250 |

0 |

-1.1 |

.261 |

73 |

24 |

| Jordan Thompson |

409 |

.195 |

.255 |

.307 |

58 |

.112 |

.276 |

-4 |

-1.1 |

.250 |

61 |

33 |

| Wilman Diaz |

321 |

.204 |

.260 |

.306 |

59 |

.102 |

.313 |

-4 |

-1.1 |

.251 |

65 |

26 |

| Sean McLain |

430 |

.184 |

.263 |

.267 |

50 |

.083 |

.255 |

-2 |

-1.2 |

.242 |

52 |

30 |

| Eduardo Guerrero |

395 |

.194 |

.289 |

.249 |

54 |

.056 |

.254 |

-8 |

-1.5 |

.250 |

57 |

27 |

| Joe Vetrano |

404 |

.202 |

.265 |

.321 |

64 |

.119 |

.289 |

-2 |

-1.6 |

.260 |

68 |

35 |

| Samuel Munoz |

515 |

.200 |

.266 |

.329 |

66 |

.129 |

.258 |

0 |

-1.6 |

.261 |

75 |

44 |

| Mairoshendrick Martinus |

405 |

.188 |

.240 |

.298 |

50 |

.110 |

.278 |

-9 |

-1.9 |

.237 |

60 |

30 |

| John Rhodes |

438 |

.186 |

.260 |

.290 |

55 |

.104 |

.253 |

0 |

-2.0 |

.248 |

58 |

31 |

| Bubba Alleyne |

314 |

.175 |

.227 |

.261 |

37 |

.086 |

.247 |

-8 |

-2.3 |

.217 |

38 |

21 |

| Jackson Nicklaus |

309 |

.146 |

.239 |

.248 |

38 |

.102 |

.298 |

-3 |

-2.3 |

.225 |

45 |

16 |

Batters – Top Near-Age Offensive Comps

Batters – 80th/20th Percentiles

| Player |

80th BA |

80th OBP |

80th SLG |

80th OPS+ |

80th WAR |

20th BA |

20th OBP |

20th SLG |

20th OPS+ |

20th WAR |

| Shohei Ohtani |

.313 |

.414 |

.707 |

208 |

8.8 |

.262 |

.359 |

.551 |

155 |

4.6 |

| Mookie Betts |

.300 |

.389 |

.522 |

152 |

5.3 |

.249 |

.334 |

.419 |

111 |

2.4 |

| Freddie Freeman |

.311 |

.396 |

.544 |

160 |

4.2 |

.262 |

.346 |

.440 |

121 |

1.6 |

| Will Smith |

.285 |

.379 |

.513 |

145 |

4.1 |

.229 |

.325 |

.384 |

99 |

1.6 |

| Andy Pages |

.283 |

.338 |

.518 |

135 |

3.9 |

.232 |

.289 |

.405 |

94 |

1.1 |

| Alex Freeland |

.256 |

.349 |

.457 |

121 |

3.7 |

.210 |

.300 |

.350 |

82 |

1.0 |

| Dalton Rushing |

.260 |

.358 |

.497 |

134 |

2.7 |

.203 |

.302 |

.357 |

85 |

0.6 |

| Max Muncy |

.241 |

.372 |

.500 |

141 |

2.8 |

.193 |

.319 |

.367 |

97 |

0.7 |

| Tommy Edman |

.277 |

.334 |

.464 |

121 |

2.7 |

.221 |

.278 |

.361 |

79 |

0.7 |

| Alex Call |

.270 |

.380 |

.462 |

135 |

2.6 |

.218 |

.323 |

.348 |

91 |

0.7 |

| Teoscar Hernández |

.292 |

.344 |

.536 |

141 |

2.9 |

.240 |

.290 |

.425 |

100 |

0.1 |

| Ryan Ward |

.261 |

.323 |

.515 |

129 |

3.2 |

.211 |

.274 |

.394 |

86 |

0.1 |

| Miguel Rojas |

.281 |

.339 |

.414 |

109 |

1.8 |

.222 |

.284 |

.325 |

72 |

0.4 |

| Zach Ehrhard |

.256 |

.329 |

.434 |

112 |

2.2 |

.205 |

.283 |

.333 |

71 |

-0.3 |

| Andy Ibáñez |

.266 |

.333 |

.436 |

111 |

1.7 |

.214 |

.279 |

.343 |

74 |

0.1 |

| Kole Myers |

.268 |

.374 |

.362 |

108 |

2.0 |

.209 |

.314 |

.278 |

68 |

0.0 |

| Austin Gauthier |

.258 |

.366 |

.373 |

108 |

1.8 |

.206 |

.311 |

.290 |

72 |

-0.3 |

| Ryan Fitzgerald |

.250 |

.326 |

.439 |

112 |

1.5 |

.198 |

.276 |

.339 |

75 |

0.0 |

| Kody Hoese |

.261 |

.323 |

.437 |

108 |

1.6 |

.211 |

.273 |

.339 |

70 |

-0.3 |

| Matt Gorski |

.255 |

.298 |

.511 |

120 |

1.7 |

.202 |

.244 |

.382 |

72 |

-0.4 |

| Chris Newell |

.233 |

.310 |

.455 |

109 |

1.6 |

.182 |

.258 |

.340 |

66 |

-0.9 |

| Michael Siani |

.234 |

.305 |

.338 |

81 |

1.6 |

.177 |

.251 |

.259 |

47 |

-0.4 |

| Eduardo Quintero |

.244 |

.331 |

.421 |

109 |

1.6 |

.192 |

.279 |

.314 |

70 |

-0.9 |

| Hyeseong Kim |

.264 |

.302 |

.403 |

95 |

1.1 |

.214 |

.252 |

.319 |

62 |

-0.4 |

| Michael Conforto |

.251 |

.344 |

.471 |

125 |

1.4 |

.200 |

.295 |

.354 |

81 |

-0.8 |

| Elijah Hainline |

.231 |

.325 |

.364 |

93 |

1.4 |

.175 |

.272 |

.270 |

54 |

-0.8 |

| James Tibbs III |

.242 |

.335 |

.429 |

111 |

1.5 |

.189 |

.283 |

.317 |

70 |

-1.1 |

| Josue De Paula |

.248 |

.346 |

.404 |

109 |

1.0 |

.195 |

.293 |

.302 |

70 |

-1.2 |

| Nelson Quiroz |

.289 |

.333 |

.380 |

99 |

0.5 |

.224 |

.268 |

.296 |

59 |

-0.5 |

| CJ Alexander |

.250 |

.310 |

.453 |

110 |

1.1 |

.195 |

.249 |

.343 |

66 |

-1.1 |

| Taylor Young |

.242 |

.330 |

.325 |

84 |

1.0 |

.191 |

.275 |

.253 |

52 |

-1.1 |

| Chuckie Robinson |

.253 |

.305 |

.365 |

88 |

0.8 |

.194 |

.243 |

.276 |

47 |

-0.8 |

| Chris Okey |

.257 |

.300 |

.376 |

90 |

0.3 |

.195 |

.235 |

.272 |

44 |

-0.6 |

| Griffin Lockwood-Powell |

.238 |

.318 |

.379 |

95 |

0.7 |

.182 |

.257 |

.284 |

55 |

-1.0 |

| Logan Wagner |

.210 |

.308 |

.360 |

85 |

1.0 |

.157 |

.255 |

.265 |

48 |

-1.2 |

| Noah Miller |

.246 |

.294 |

.341 |

77 |

0.8 |

.194 |

.240 |

.271 |

43 |

-1.2 |

| Carlos Rojas |

.242 |

.297 |

.312 |

70 |

0.2 |

.179 |

.235 |

.234 |

33 |

-0.9 |

| Nick Senzel |

.250 |

.324 |

.411 |

103 |

0.6 |

.198 |

.268 |

.314 |

64 |

-1.1 |

| Enrique Hernández |

.243 |

.301 |

.414 |

98 |

0.5 |

.194 |

.253 |

.317 |

59 |

-1.1 |

| Frank Rodriguez |

.220 |

.285 |

.334 |

72 |

0.1 |

.160 |

.225 |

.237 |

30 |

-0.9 |

| Jake Gelof |

.205 |

.277 |

.386 |

83 |

0.6 |

.155 |

.227 |

.279 |

44 |

-1.2 |

| Kendall George |

.264 |

.345 |

.330 |

91 |

0.6 |

.210 |

.291 |

.264 |

57 |

-1.6 |

| Kendall Simmons |

.225 |

.286 |

.398 |

88 |

0.1 |

.168 |

.230 |

.279 |

44 |

-1.1 |

| Zyhir Hope |

.236 |

.312 |

.390 |

95 |

0.5 |

.184 |

.262 |

.296 |

58 |

-1.7 |

| Ezequiel Pagan |

.265 |

.309 |

.394 |

97 |

0.3 |

.210 |

.256 |

.305 |

59 |

-1.3 |

| Mike Sirota |

.238 |

.329 |

.411 |

105 |

0.2 |

.180 |

.273 |

.309 |

65 |

-1.1 |

| Damon Keith |

.245 |

.308 |

.424 |

103 |

0.3 |

.192 |

.257 |

.317 |

63 |

-1.5 |

| Kyle Nevin |

.256 |

.312 |

.411 |

102 |

0.4 |

.205 |

.261 |

.312 |

62 |

-1.4 |

| Trei Cruz |

.225 |

.282 |

.398 |

89 |

0.2 |

.169 |

.231 |

.292 |

49 |

-1.4 |

| Eliezer Alfonzo |

.258 |

.297 |

.357 |

81 |

0.0 |

.194 |

.233 |

.268 |

40 |

-1.6 |

| Yeiner Fernandez |

.258 |

.322 |

.333 |

83 |

-0.1 |

.203 |

.261 |

.260 |

48 |

-2.0 |

| Cameron Decker |

.199 |

.281 |

.405 |

88 |

-0.2 |

.148 |

.227 |

.291 |

45 |

-1.8 |

| Jordan Thompson |

.218 |

.277 |

.354 |

75 |

-0.3 |

.169 |

.232 |

.264 |

40 |

-1.9 |

| Wilman Diaz |

.231 |

.286 |

.361 |

77 |

-0.4 |

.179 |

.230 |

.264 |

38 |

-1.9 |

| Sean McLain |

.206 |

.284 |

.307 |

65 |

-0.4 |

.158 |

.238 |

.230 |

35 |

-2.0 |

| Eduardo Guerrero |

.219 |

.317 |

.289 |

69 |

-0.7 |

.169 |

.265 |

.220 |

39 |

-2.1 |

| Joe Vetrano |

.233 |

.291 |

.365 |

82 |

-0.7 |

.180 |

.235 |

.276 |

45 |

-2.5 |

| Samuel Munoz |

.224 |

.290 |

.375 |

85 |

-0.5 |

.175 |

.241 |

.286 |

50 |

-2.6 |

| Mairoshendrick Martinus |

.213 |

.267 |

.347 |

70 |

-1.0 |

.163 |

.215 |

.255 |

33 |

-2.8 |

| John Rhodes |

.211 |

.286 |

.329 |

72 |

-1.1 |

.164 |

.234 |

.246 |

38 |

-2.9 |

| Bubba Alleyne |

.196 |

.249 |

.304 |

53 |

-1.7 |

.152 |

.204 |

.227 |

22 |

-2.9 |

| Jackson Nicklaus |

.173 |

.269 |

.301 |

59 |

-1.5 |

.119 |

.214 |

.196 |

19 |

-3.0 |

Batters – Platoon Splits

| Player |

BA vs. L |

OBP vs. L |

SLG vs. L |

BA vs. R |

OBP vs. R |

SLG vs. R |

| Shohei Ohtani |

.275 |

.367 |

.566 |

.295 |

.400 |

.645 |

| Mookie Betts |

.280 |

.371 |

.476 |

.272 |

.357 |

.465 |

| Freddie Freeman |

.270 |

.344 |

.459 |

.296 |

.384 |

.510 |

| Will Smith |

.258 |

.364 |

.458 |

.256 |

.352 |

.444 |

| Andy Pages |

.270 |

.329 |

.505 |

.251 |

.306 |

.434 |

| Alex Freeland |

.221 |

.313 |

.379 |

.235 |

.330 |

.404 |

| Dalton Rushing |

.234 |

.336 |

.404 |

.231 |

.329 |

.438 |

| Max Muncy |

.209 |

.330 |

.407 |

.221 |

.355 |

.454 |

| Tommy Edman |

.255 |

.304 |

.462 |

.249 |

.305 |

.392 |

| Alex Call |

.252 |

.366 |

.429 |

.238 |

.345 |

.386 |

| Teoscar Hernández |

.278 |

.331 |

.521 |

.262 |

.313 |

.471 |

| Ryan Ward |

.220 |

.280 |

.387 |

.240 |

.306 |

.475 |

| Miguel Rojas |

.259 |

.319 |

.388 |

.253 |

.310 |

.364 |

| Zach Ehrhard |

.229 |

.314 |

.386 |

.229 |

.304 |

.378 |

| Andy Ibáñez |

.262 |

.322 |

.415 |

.230 |

.292 |

.372 |

| Kole Myers |

.231 |

.336 |

.306 |

.243 |

.344 |

.324 |

| Austin Gauthier |

.235 |

.350 |

.341 |

.234 |

.336 |

.331 |

| Ryan Fitzgerald |

.215 |

.286 |

.364 |

.229 |

.306 |

.405 |

| Kody Hoese |

.244 |

.307 |

.409 |

.232 |

.292 |

.371 |

| Matt Gorski |

.229 |

.276 |

.466 |

.226 |

.266 |

.433 |

| Chris Newell |

.198 |

.269 |

.366 |

.209 |

.290 |

.406 |

| Michael Siani |

.204 |

.276 |

.292 |

.204 |

.280 |

.294 |

| Eduardo Quintero |

.219 |

.312 |

.380 |

.214 |

.301 |

.359 |

| Hyeseong Kim |

.227 |

.272 |

.351 |

.241 |

.279 |

.363 |

| Michael Conforto |

.216 |

.296 |

.373 |

.229 |

.326 |

.423 |

| Elijah Hainline |

.208 |

.316 |

.338 |

.199 |

.291 |

.301 |

| James Tibbs III |

.205 |

.292 |

.346 |

.216 |

.312 |

.383 |

| Josue De Paula |

.220 |

.313 |

.356 |

.221 |

.322 |

.355 |

| Nelson Quiroz |

.250 |

.288 |

.286 |

.259 |

.307 |

.360 |

| CJ Alexander |

.211 |

.261 |

.359 |

.227 |

.286 |

.418 |

| Taylor Young |

.222 |

.311 |

.299 |

.214 |

.298 |

.283 |

| Chuckie Robinson |

.228 |

.275 |

.317 |

.216 |

.268 |

.316 |

| Chris Okey |

.224 |

.262 |

.310 |

.218 |

.263 |

.318 |

| Griffin Lockwood-Powell |

.206 |

.297 |

.340 |

.208 |

.286 |

.323 |

| Logan Wagner |

.186 |

.277 |

.307 |

.183 |

.283 |

.305 |

| Noah Miller |

.214 |

.258 |

.303 |

.221 |

.268 |

.303 |

| Carlos Rojas |

.215 |

.276 |

.291 |

.210 |

.263 |

.261 |

| Nick Senzel |

.236 |

.305 |

.396 |

.218 |

.291 |

.339 |

| Enrique Hernández |

.225 |

.291 |

.375 |

.215 |

.267 |

.350 |

| Frank Rodriguez |

.196 |

.262 |

.286 |

.186 |

.248 |

.280 |

| Jake Gelof |

.186 |

.259 |

.330 |

.178 |

.247 |

.331 |

| Kendall George |

.224 |

.295 |

.280 |

.242 |

.324 |

.300 |

| Kendall Simmons |

.197 |

.260 |

.324 |

.196 |

.256 |

.336 |

| Zyhir Hope |

.198 |

.281 |

.305 |

.213 |

.294 |

.352 |

| Ezequiel Pagan |

.225 |

.266 |

.333 |

.242 |

.289 |

.352 |

| Mike Sirota |

.215 |

.323 |

.367 |

.202 |

.288 |

.345 |

| Damon Keith |

.225 |

.299 |

.392 |

.212 |

.272 |

.359 |

| Kyle Nevin |

.243 |

.305 |

.393 |

.221 |

.275 |

.336 |

| Trei Cruz |

.183 |

.238 |

.280 |

.202 |

.264 |

.358 |

| Eliezer Alfonzo |

.226 |

.263 |

.323 |

.225 |

.264 |

.303 |

| Yeiner Fernandez |

.227 |

.295 |

.295 |

.231 |

.293 |

.297 |

| Cameron Decker |

.173 |

.253 |

.333 |

.173 |

.255 |

.341 |

| Jordan Thompson |

.204 |

.260 |

.327 |

.192 |

.253 |

.299 |

| Wilman Diaz |

.213 |

.272 |

.309 |

.200 |

.255 |

.305 |

| Sean McLain |

.185 |

.271 |

.286 |

.184 |

.260 |

.258 |

| Eduardo Guerrero |

.194 |

.288 |

.262 |

.193 |

.289 |

.244 |

| Joe Vetrano |

.196 |

.255 |

.314 |

.204 |

.269 |

.323 |

| Samuel Munoz |

.188 |

.254 |

.305 |

.205 |

.271 |

.338 |

| Mairoshendrick Martinus |

.193 |

.254 |

.325 |

.185 |

.233 |

.286 |

| John Rhodes |

.190 |

.266 |

.302 |

.185 |

.258 |

.284 |

| Bubba Alleyne |

.176 |

.220 |

.247 |

.175 |

.230 |

.267 |

| Jackson Nicklaus |

.139 |

.227 |

.203 |

.149 |

.244 |

.267 |

Pitchers – Standard

| Player |

T |

Age |

W |

L |

ERA |

G |

GS |

IP |

H |

ER |

HR |

BB |

SO |

| Yoshinobu Yamamoto |

R |

27 |

13 |

7 |

3.31 |

28 |

28 |

168.7 |

129 |

62 |

18 |

43 |

180 |

| Blake Snell |

L |

33 |

8 |

5 |

3.55 |

21 |

21 |

106.3 |

83 |

42 |

12 |

48 |

134 |

| Tyler Glasnow |

R |

32 |

5 |

4 |

3.76 |

21 |

20 |

105.3 |

85 |

44 |

14 |

39 |

123 |

| Shohei Ohtani |

R |

31 |

5 |

3 |

3.57 |

16 |

16 |

80.7 |

59 |

32 |

11 |

31 |

98 |

| Clayton Kershaw |

L |

38 |

7 |

5 |

4.21 |

24 |

21 |

109.0 |

106 |

51 |

13 |

35 |

84 |

| Edwin Díaz |

R |

32 |

6 |

2 |

2.93 |

57 |

0 |

58.3 |

41 |

19 |

6 |

20 |

84 |

| Emmet Sheehan |

R |

26 |

5 |

4 |

4.00 |

24 |

17 |

88.0 |

72 |

39 |

12 |

31 |

101 |

| Roki Sasaki |

R |

24 |

5 |

4 |

4.11 |

22 |

16 |

85.3 |

76 |

39 |

12 |

29 |

98 |

| Justin Wrobleski |

L |

25 |

6 |

6 |

4.42 |

31 |

15 |

110.0 |

106 |

54 |

16 |

35 |

103 |

| Tanner Scott |

L |

31 |

5 |

3 |

3.50 |

63 |

0 |

61.7 |

50 |

24 |

6 |

23 |

69 |

| Alex Vesia |

L |

30 |

5 |

3 |

3.41 |

68 |

0 |

60.7 |

45 |

23 |

8 |

25 |

78 |

| Evan Phillips |

R |

31 |

4 |

2 |

3.35 |

57 |

0 |

53.7 |

44 |

20 |

6 |

16 |

57 |

| Gavin Stone |

R |

27 |

5 |

5 |

4.66 |

19 |

18 |

92.7 |

92 |

48 |

13 |

32 |

80 |

| Michael Kopech |

R |

30 |

6 |

5 |

4.43 |

38 |

13 |

83.3 |

69 |

41 |

13 |

44 |

90 |

| Andrew Heaney |

L |

35 |

7 |

8 |

4.92 |

28 |

25 |

122.7 |

130 |

67 |

21 |

42 |

103 |

| Brusdar Graterol |

R |

27 |

3 |

1 |

3.45 |

45 |

0 |

47.0 |

42 |

18 |

4 |

11 |

38 |

| Tony Gonsolin |

R |

32 |

4 |

5 |

4.90 |

14 |

14 |

71.7 |

63 |

39 |

12 |

26 |

64 |

| Jack Dreyer |

L |

27 |

3 |

2 |

4.19 |

59 |

4 |

66.7 |

58 |

31 |

9 |

25 |

68 |

| Jackson Ferris |

L |

22 |

7 |

8 |

5.20 |

25 |

24 |

117.7 |

117 |

68 |

18 |

54 |

101 |

| Landon Knack |

R |

28 |

6 |

8 |

5.16 |

26 |

22 |

122.0 |

122 |

70 |

21 |

48 |

105 |

| Kyle Hurt |

R |

28 |

4 |

4 |

4.77 |

23 |

13 |

66.0 |

60 |

35 |

9 |

35 |

70 |

| Bobby Miller |

R |

27 |

4 |

6 |

5.04 |

28 |

17 |

94.7 |

91 |

53 |

13 |

41 |

89 |

| Michael Grove |

R |

29 |

3 |

2 |

4.68 |

24 |

9 |

57.7 |

57 |

30 |

8 |

19 |

55 |

| Matt Sauer |

R |

27 |

5 |

5 |

5.03 |

25 |

15 |

93.0 |

96 |

52 |

14 |

31 |

76 |

| River Ryan |

R |

27 |

2 |

3 |

4.92 |

16 |

15 |

60.3 |

60 |

33 |

9 |

27 |

50 |

| Ben Casparius |

R |

27 |

6 |

6 |

4.80 |

37 |

9 |

80.7 |

78 |

43 |

12 |

32 |

77 |

| Zach Penrod |

L |

29 |

3 |

2 |

4.70 |

26 |

8 |

44.0 |

43 |

23 |

5 |

22 |

37 |

| Wyatt Crowell |

L |

24 |

4 |

6 |

5.23 |

23 |

18 |

82.7 |

77 |

48 |

11 |

42 |

74 |

| Garrett McDaniels |

L |

26 |

3 |

2 |

4.67 |

36 |

5 |

52.0 |

50 |

27 |

6 |

26 |

46 |

| Blake Treinen |

R |

38 |

4 |

3 |

4.09 |

39 |

1 |

33.0 |

31 |

15 |

4 |

12 |

37 |

| Chris Campos |

R |

25 |

5 |

7 |

5.26 |

23 |

19 |

102.7 |

111 |

60 |

18 |

29 |

76 |

| José Rodríguez |

R |

24 |

5 |

6 |

4.75 |

36 |

4 |

60.7 |

55 |

32 |

9 |

30 |

66 |

| Brock Stewart |

R |

34 |

1 |

1 |

4.01 |

36 |

0 |

33.7 |

29 |

15 |

4 |

14 |

38 |

| Anthony Banda |

L |

32 |

3 |

2 |

4.66 |

56 |

3 |

56.0 |

54 |

29 |

8 |

25 |

53 |

| Edgardo Henriquez |

R |

24 |

2 |

3 |

4.66 |

41 |

4 |

46.3 |

41 |

24 |

6 |

23 |

50 |

| Nick Frasso |

R |

27 |

3 |

4 |

5.01 |

34 |

11 |

73.7 |

75 |

41 |

11 |

30 |

60 |

| Peter Heubeck |

R |

23 |

3 |

5 |

5.50 |

19 |

19 |

73.7 |

71 |

45 |

11 |

42 |

63 |

| Antoine Kelly |

L |

26 |

3 |

3 |

5.16 |

33 |

5 |

52.3 |

49 |

30 |

7 |

29 |

48 |

| Carson Hobbs |

R |

24 |

5 |

5 |

4.67 |

40 |

0 |

44.3 |

42 |

23 |

6 |

21 |

42 |

| Christian Romero |

R |

23 |

4 |

5 |

5.52 |

23 |

14 |

89.7 |

96 |

55 |

14 |

32 |

57 |

| Patrick Copen |

R |

24 |

4 |

6 |

5.49 |

24 |

24 |

98.3 |

94 |

60 |

14 |

63 |

90 |

| Paul Gervase |

R |

26 |

3 |

4 |

4.87 |

43 |

1 |

57.3 |

50 |

31 |

9 |

30 |

62 |

| Roque Gutierrez |

R |

23 |

3 |

5 |

5.40 |

23 |

9 |

83.3 |

87 |

50 |

14 |

34 |

67 |

| Jose Hernandez |

L |

28 |

2 |

3 |

4.98 |

30 |

1 |

34.3 |

32 |

19 |

5 |

18 |

33 |

| Will Klein |

R |

26 |

3 |

4 |

4.79 |

48 |

0 |

56.3 |

50 |

30 |

6 |

35 |

59 |

| Ronan Kopp |

L |

23 |

3 |

2 |

4.83 |

46 |

0 |

54.0 |

47 |

29 |

7 |

35 |

59 |

| Justin Jarvis |

R |

26 |

4 |

6 |

5.66 |

19 |

14 |

76.3 |

82 |

48 |

13 |

35 |

56 |

| J.P. Feyereisen |

R |

33 |

2 |

3 |

5.46 |

25 |

2 |

31.3 |

34 |

19 |

6 |

11 |

22 |

| Jared Karros |

R |

25 |

2 |

4 |

5.82 |

13 |

13 |

55.7 |

63 |

36 |

11 |

19 |

35 |

| Luke Fox |

L |

24 |

3 |

4 |

5.79 |

19 |

18 |

79.3 |

79 |

51 |

14 |

42 |

67 |

| Jose Adames |

R |

33 |

2 |

3 |

5.34 |

28 |

0 |

32.0 |

30 |

19 |

4 |

20 |

32 |

| Chris Stratton |

R |

35 |

2 |

2 |

5.27 |

35 |

0 |

41.0 |

42 |

24 |

6 |

17 |

36 |

| Logan Boyer |

R |

28 |

4 |

4 |

5.13 |

43 |

0 |

47.3 |

47 |

27 |

6 |

27 |

39 |

| Lucas Wepf |

R |

26 |

2 |

3 |

5.26 |

31 |

0 |

37.7 |

36 |

22 |

6 |

18 |

38 |

| Nick Nastrini |

R |

26 |

4 |

5 |

5.81 |

23 |

16 |

79.0 |

77 |

51 |

14 |

50 |

69 |

| Carlos Duran |

R |

24 |

2 |

2 |

5.75 |

30 |

7 |

56.3 |

56 |

36 |

9 |

36 |

51 |

| Kelvin Ramirez |

R |

25 |

2 |

4 |

5.32 |

41 |

0 |

45.7 |

46 |

27 |

7 |

25 |

39 |

| Tanner Kiest |

R |

31 |

2 |

4 |

5.74 |

24 |

0 |

31.3 |

33 |

20 |

5 |

16 |

26 |

| Ben Harris |

L |

26 |

2 |

2 |

5.54 |

35 |

1 |

37.3 |

34 |

23 |

5 |

29 |

38 |

| Michael Martinez |

R |

26 |

2 |

4 |

5.54 |

34 |

0 |

39.0 |

38 |

24 |

6 |

20 |

33 |

| Antonio Knowles |

R |

26 |

3 |

4 |

5.28 |

38 |

0 |

44.3 |

42 |

26 |

7 |

23 |

41 |

| Jerming Rosario |

R |

24 |

3 |

6 |

5.71 |

34 |

11 |

75.7 |

76 |

48 |

12 |

45 |

66 |

| Jacob Meador |

R |

25 |

3 |

4 |

5.98 |

24 |

12 |

58.7 |

63 |

39 |

10 |

32 |

42 |

| Christian Suarez |

L |

25 |

3 |

4 |

5.47 |

40 |

0 |

54.3 |

55 |

33 |

8 |

36 |

46 |

| Kelvin Bautista |

L |

26 |

3 |

4 |

5.68 |

38 |

0 |

44.3 |

46 |

28 |

6 |

31 |

34 |

| Ryan Sublette |

R |

27 |

3 |

6 |

5.77 |

36 |

1 |

48.3 |

47 |

31 |

7 |

32 |

44 |

| Jorge Benitez |

L |

27 |

2 |

3 |

6.17 |

34 |

0 |

42.3 |

41 |

29 |

6 |

30 |

35 |

Pitchers – Advanced

| Player |

IP |

K/9 |

BB/9 |

HR/9 |

BB% |

K% |

BABIP |

ERA+ |

3ERA+ |

FIP |

ERA- |

WAR |

| Yoshinobu Yamamoto |

168.7 |

9.6 |

2.3 |

1.0 |

6.4% |

26.7% |

.261 |

130 |

127 |

3.27 |

77 |

3.9 |

| Blake Snell |

106.3 |

11.3 |

4.1 |

1.0 |

10.6% |

29.6% |

.284 |

121 |

114 |

3.52 |

83 |

2.1 |

| Tyler Glasnow |

105.3 |

10.5 |

3.3 |

1.2 |

8.8% |

27.8% |

.276 |

114 |

109 |

3.70 |

88 |

1.9 |

| Shohei Ohtani |

80.7 |

10.9 |

3.5 |

1.2 |

9.3% |

29.3% |

.257 |

120 |

115 |

3.85 |

83 |

1.5 |

| Clayton Kershaw |

109.0 |

6.9 |

2.9 |

1.1 |

7.5% |

18.1% |

.284 |

102 |

94 |

4.22 |

98 |

1.5 |

| Edwin Díaz |

58.3 |

13.0 |

3.1 |

0.9 |

8.4% |

35.4% |

.285 |

147 |

135 |

2.91 |

68 |

1.3 |

| Emmet Sheehan |

88.0 |

10.3 |

3.2 |

1.2 |

8.5% |

27.8% |

.276 |

108 |

106 |

3.83 |

93 |

1.3 |

| Roki Sasaki |

85.3 |

10.3 |

3.1 |

1.3 |

8.0% |

27.1% |

.295 |

104 |

107 |

3.93 |

96 |

1.3 |

| Justin Wrobleski |

110.0 |

8.4 |

2.9 |

1.3 |

7.5% |

22.1% |

.291 |

97 |

101 |

4.25 |

103 |

1.1 |

| Tanner Scott |

61.7 |

10.1 |

3.4 |

0.9 |

9.0% |

27.1% |

.282 |

123 |

120 |

3.46 |

81 |

1.0 |

| Alex Vesia |

60.7 |

11.6 |

3.7 |

1.2 |

9.9% |

31.0% |

.268 |

126 |

122 |

3.69 |

79 |

0.9 |

| Evan Phillips |

53.7 |

9.6 |

2.7 |

1.0 |

7.3% |

26.0% |

.273 |

128 |

123 |

3.50 |

78 |

0.9 |

| Gavin Stone |

92.7 |

7.8 |

3.1 |

1.3 |

8.0% |

20.1% |

.293 |

92 |

94 |

4.36 |

109 |

0.8 |

| Michael Kopech |

83.3 |

9.7 |

4.8 |

1.4 |

12.1% |

24.7% |

.265 |

97 |

96 |

4.80 |

103 |

0.7 |

| Andrew Heaney |

122.7 |

7.6 |

3.1 |

1.5 |

7.9% |

19.3% |

.299 |

87 |

81 |

4.96 |

114 |

0.6 |

| Brusdar Graterol |

47.0 |

7.3 |

2.1 |

0.8 |

5.8% |

19.9% |

.277 |

125 |

126 |

3.42 |

80 |

0.6 |

| Tony Gonsolin |

71.7 |

8.0 |

3.3 |

1.5 |

8.6% |

21.3% |

.259 |

88 |

85 |

4.81 |

114 |

0.5 |

| Jack Dreyer |

66.7 |

9.2 |

3.4 |

1.2 |

8.9% |

24.2% |

.277 |

103 |

104 |

4.05 |

97 |

0.4 |

| Jackson Ferris |

117.7 |

7.7 |

4.1 |

1.4 |

10.3% |

19.3% |

.289 |

83 |

89 |

5.02 |

120 |

0.4 |

| Landon Knack |

122.0 |

7.7 |

3.5 |

1.5 |

9.0% |

19.8% |

.286 |

83 |

85 |

4.93 |

120 |

0.4 |

| Kyle Hurt |

66.0 |

9.5 |

4.8 |

1.2 |

11.7% |

23.5% |

.291 |

90 |

91 |

4.59 |

111 |

0.4 |

| Bobby Miller |

94.7 |

8.5 |

3.9 |

1.2 |

9.8% |

21.3% |

.293 |

85 |

87 |

4.49 |

117 |

0.4 |

| Michael Grove |

57.7 |

8.6 |

3.0 |

1.2 |

7.7% |

22.2% |

.301 |

92 |

91 |

4.20 |

109 |

0.4 |

| Matt Sauer |

93.0 |

7.4 |

3.0 |

1.4 |

7.7% |

18.8% |

.295 |

85 |

87 |

4.74 |

117 |

0.3 |

| River Ryan |

60.3 |

7.5 |

4.0 |

1.3 |

10.1% |

18.7% |

.287 |

87 |

90 |

4.99 |

115 |

0.3 |

| Ben Casparius |

80.7 |

8.6 |

3.6 |

1.3 |

9.1% |

22.0% |

.293 |

90 |

92 |

4.53 |

111 |

0.3 |

| Zach Penrod |

44.0 |

7.6 |

4.5 |

1.0 |

11.1% |

18.7% |

.292 |

91 |

91 |

4.66 |

110 |

0.3 |

| Wyatt Crowell |

82.7 |

8.1 |

4.6 |

1.2 |

11.5% |

20.3% |

.282 |

82 |

88 |

5.10 |

122 |

0.2 |

| Garrett McDaniels |

52.0 |

8.0 |

4.5 |

1.0 |

11.2% |

19.7% |

.293 |

92 |

96 |

4.62 |

109 |

0.2 |

| Blake Treinen |

33.0 |

10.1 |

3.3 |

1.1 |

8.5% |

26.2% |

.310 |

105 |

91 |

3.77 |

95 |

0.2 |

| Chris Campos |

102.7 |

6.7 |

2.5 |

1.6 |

6.5% |

17.2% |

.293 |

82 |

87 |

4.90 |

122 |

0.2 |

| José Rodríguez |

60.7 |

9.8 |

4.4 |

1.3 |

11.0% |

24.3% |

.291 |

91 |

97 |

4.55 |

110 |

0.2 |

| Brock Stewart |

33.7 |

10.2 |

3.7 |

1.1 |

9.7% |

26.4% |

.291 |

107 |

97 |

3.88 |

93 |

0.2 |

| Anthony Banda |

56.0 |

8.5 |

4.0 |

1.3 |

10.1% |

21.5% |

.293 |

92 |

90 |

4.63 |

109 |

0.1 |

| Edgardo Henriquez |

46.3 |

9.7 |

4.5 |

1.2 |

11.1% |

24.2% |

.289 |

92 |

98 |

4.44 |

109 |

0.1 |

| Nick Frasso |

73.7 |

7.3 |

3.7 |

1.3 |

9.2% |

18.4% |

.291 |

86 |

88 |

4.90 |

116 |

0.1 |

| Peter Heubeck |

73.7 |

7.7 |

5.1 |

1.3 |

12.6% |

18.9% |

.282 |

78 |

84 |

5.31 |

128 |

-0.1 |

| Antoine Kelly |

52.3 |

8.3 |

5.0 |

1.2 |

12.3% |

20.4% |

.286 |

83 |

87 |

5.07 |

120 |

-0.1 |

| Carson Hobbs |

44.3 |

8.5 |

4.3 |

1.2 |

10.8% |

21.5% |

.290 |

92 |

97 |

4.58 |

109 |

-0.1 |

| Christian Romero |

89.7 |

5.7 |

3.2 |

1.4 |

8.1% |

14.5% |

.286 |

78 |

83 |

5.36 |

128 |

-0.1 |

| Patrick Copen |

98.3 |

8.2 |

5.8 |

1.3 |

13.9% |

19.9% |

.288 |

78 |

83 |

5.41 |

128 |

-0.1 |

| Paul Gervase |

57.3 |

9.7 |

4.7 |

1.4 |

11.9% |

24.5% |

.279 |

88 |

93 |

4.82 |

114 |

-0.1 |

| Roque Gutierrez |

83.3 |

7.2 |

3.7 |

1.5 |

9.2% |

18.2% |

.292 |

80 |

85 |

5.04 |

125 |

-0.1 |

| Jose Hernandez |

34.3 |

8.7 |

4.7 |

1.3 |

11.8% |

21.6% |

.284 |

86 |

87 |

4.79 |

116 |

-0.1 |

| Will Klein |

56.3 |

9.4 |

5.6 |

1.0 |

13.7% |

23.0% |

.293 |

90 |

94 |

4.48 |

112 |

-0.1 |

| Ronan Kopp |

54.0 |

9.8 |

5.8 |

1.2 |

14.2% |

24.0% |

.288 |

89 |

95 |

4.72 |

113 |

-0.2 |

| Justin Jarvis |

76.3 |

6.6 |

4.1 |

1.5 |

10.1% |

16.2% |

.292 |

76 |

79 |

5.36 |

132 |

-0.2 |

| J.P. Feyereisen |

31.3 |

6.3 |

3.2 |

1.7 |

8.1% |

16.2% |

.289 |

79 |

75 |

5.30 |

127 |

-0.2 |

| Jared Karros |

55.7 |

5.7 |

3.1 |

1.8 |

7.6% |

14.1% |

.289 |

74 |

79 |

5.55 |

135 |

-0.2 |

| Luke Fox |

79.3 |

7.6 |

4.8 |

1.6 |

11.8% |

18.8% |

.283 |

74 |

81 |

5.51 |

135 |

-0.2 |

| Jose Adames |

32.0 |

9.0 |

5.6 |

1.1 |

13.5% |

21.6% |

.295 |

80 |

76 |

5.04 |

124 |

-0.3 |

| Chris Stratton |

41.0 |

7.9 |

3.7 |

1.3 |

9.4% |

19.9% |

.300 |

82 |

76 |

4.63 |

122 |

-0.3 |

| Logan Boyer |

47.3 |

7.4 |

5.1 |

1.1 |

12.5% |

18.1% |

.293 |

84 |

85 |

5.00 |

119 |

-0.3 |

| Lucas Wepf |

37.7 |

9.1 |

4.3 |

1.4 |

10.7% |

22.6% |

.291 |

82 |

88 |

4.89 |

122 |

-0.3 |

| Nick Nastrini |

79.0 |

7.9 |

5.7 |

1.6 |

13.6% |

18.8% |

.280 |

74 |

77 |

5.85 |

135 |

-0.3 |

| Carlos Duran |

56.3 |

8.1 |

5.8 |

1.4 |

13.7% |

19.5% |

.292 |

75 |

80 |

5.67 |

134 |

-0.3 |

| Kelvin Ramirez |

45.7 |

7.7 |

4.9 |

1.4 |

11.9% |

18.6% |

.291 |

81 |

87 |

5.22 |

124 |

-0.4 |

| Tanner Kiest |

31.3 |

7.5 |

4.6 |

1.4 |

11.0% |

17.9% |

.298 |

75 |

74 |

5.40 |

134 |

-0.4 |

| Ben Harris |

37.3 |

9.2 |

7.0 |

1.2 |

16.5% |

21.6% |

.290 |

77 |

80 |

5.52 |

129 |

-0.4 |

| Michael Martinez |

39.0 |

7.6 |

4.6 |

1.4 |

11.4% |

18.8% |

.283 |

78 |

82 |

5.32 |

129 |

-0.4 |

| Antonio Knowles |

44.3 |

8.3 |

4.7 |

1.4 |

11.6% |

20.6% |

.282 |

81 |

85 |

5.19 |

123 |

-0.4 |

| Jerming Rosario |

75.7 |

7.8 |

5.4 |

1.4 |

12.8% |

18.8% |

.291 |

75 |

80 |

5.50 |

133 |

-0.4 |

| Jacob Meador |

58.7 |

6.4 |

4.9 |

1.5 |

11.9% |

15.6% |

.291 |

72 |

76 |

5.94 |

139 |

-0.4 |

| Christian Suarez |

54.3 |

7.6 |

6.0 |

1.3 |

14.0% |

17.9% |

.294 |

79 |

84 |

5.48 |

127 |

-0.5 |

| Kelvin Bautista |

44.3 |

6.9 |

6.3 |

1.2 |

14.4% |

15.7% |

.294 |

76 |

78 |

5.83 |

132 |

-0.6 |

| Ryan Sublette |

48.3 |

8.2 |

6.0 |

1.3 |

14.3% |

19.7% |

.292 |

74 |

77 |

5.58 |

135 |

-0.6 |

| Jorge Benitez |

42.3 |

7.4 |

6.4 |

1.3 |

15.1% |

17.6% |

.282 |

70 |

72 |

6.05 |

143 |

-0.7 |

Pitchers – Top Near-Age Comps

Pitchers – Splits and Percentiles

| Player |

BA vs. L |

OBP vs. L |

SLG vs. L |

BA vs. R |

OBP vs. R |

SLG vs. R |

80th WAR |

20th WAR |

80th ERA |

20th ERA |

| Yoshinobu Yamamoto |

.199 |

.254 |

.298 |

.220 |

.276 |

.390 |

5.1 |

2.8 |

2.76 |

3.86 |

| Blake Snell |

.190 |

.261 |

.304 |

.216 |

.306 |

.365 |

2.9 |

1.0 |

2.89 |

4.49 |

| Tyler Glasnow |

.219 |

.290 |

.369 |

.217 |

.288 |

.389 |

2.7 |

1.2 |

3.14 |

4.34 |

| Shohei Ohtani |

.209 |

.297 |

.388 |

.199 |

.282 |

.338 |

2.1 |

1.0 |

3.01 |

4.11 |

| Clayton Kershaw |

.242 |

.300 |

.385 |

.255 |

.315 |

.409 |

2.1 |

0.8 |

3.67 |

4.96 |

| Edwin Díaz |

.175 |

.273 |

.330 |

.211 |

.283 |

.325 |

2.2 |

0.3 |

1.95 |

4.67 |

| Emmet Sheehan |

.205 |

.284 |

.364 |

.232 |

.301 |

.390 |

2.0 |

0.4 |

3.37 |

4.85 |

| Roki Sasaki |

.241 |

.323 |

.414 |

.223 |

.287 |

.375 |

2.1 |

0.5 |

3.39 |

4.85 |

| Justin Wrobleski |

.231 |

.303 |

.369 |

.253 |

.309 |

.437 |

2.0 |

0.2 |

3.76 |

5.09 |

| Tanner Scott |

.186 |

.275 |

.271 |

.231 |

.303 |

.381 |

1.8 |

0.1 |

2.77 |

4.46 |

| Alex Vesia |

.182 |

.267 |

.325 |

.217 |

.307 |

.385 |

1.6 |

0.0 |

2.56 |

4.61 |

| Evan Phillips |

.222 |

.300 |

.367 |

.224 |

.276 |

.374 |

1.4 |

0.2 |

2.55 |

4.63 |

| Gavin Stone |

.244 |

.309 |

.402 |

.259 |

.317 |

.438 |

1.3 |

0.1 |

4.13 |

5.28 |

| Michael Kopech |

.217 |

.331 |

.406 |

.230 |

.326 |

.400 |

1.6 |

-0.2 |

3.65 |

5.44 |

| Andrew Heaney |

.272 |

.333 |

.416 |

.262 |

.331 |

.475 |

1.4 |

-0.2 |

4.31 |

5.64 |

| Brusdar Graterol |

.276 |

.329 |

.487 |

.210 |

.252 |

.270 |

0.9 |

0.1 |

2.87 |

4.32 |

| Tony Gonsolin |

.239 |

.316 |

.413 |

.233 |

.306 |

.442 |

0.9 |

-0.1 |

4.37 |

5.73 |

| Jack Dreyer |

.218 |

.296 |

.345 |

.239 |

.306 |

.423 |

1.1 |

-0.2 |

3.40 |

5.11 |

| Jackson Ferris |

.247 |

.327 |

.363 |

.254 |

.342 |

.458 |

1.1 |

-0.4 |

4.72 |

5.72 |

| Landon Knack |

.247 |

.335 |

.438 |

.262 |

.314 |

.462 |

1.3 |

-0.6 |

4.51 |

5.85 |

| Kyle Hurt |

.252 |

.348 |

.420 |

.222 |

.325 |

.378 |

0.9 |

-0.3 |

4.12 |

5.63 |

| Bobby Miller |

.229 |

.316 |

.400 |

.260 |

.333 |

.425 |

1.1 |

-0.4 |

4.38 |

5.75 |

| Michael Grove |

.255 |

.327 |

.429 |

.246 |

.303 |

.408 |

0.8 |

-0.2 |

4.06 |

5.59 |

| Matt Sauer |

.272 |

.356 |

.462 |

.249 |

.305 |

.418 |

0.9 |

-0.4 |

4.46 |

5.75 |

| River Ryan |

.254 |

.353 |

.404 |

.252 |

.321 |

.447 |

0.7 |

-0.1 |

4.42 |

5.57 |

| Ben Casparius |

.245 |

.329 |

.429 |

.249 |

.316 |

.420 |

0.9 |

-0.4 |

4.24 |

5.61 |

| Zach Penrod |

.246 |

.328 |

.386 |

.248 |

.346 |

.402 |

0.7 |

-0.2 |

3.98 |

5.77 |

| Wyatt Crowell |

.176 |

.303 |

.275 |

.274 |

.377 |

.474 |

0.7 |

-0.4 |

4.73 |

5.90 |

| Garrett McDaniels |

.212 |

.329 |

.333 |

.261 |

.344 |

.420 |

0.6 |

-0.2 |

4.07 |

5.35 |

| Blake Treinen |

.259 |

.338 |

.466 |

.219 |

.284 |

.329 |

0.7 |

-0.3 |

3.07 |

5.47 |

| Chris Campos |

.281 |

.332 |

.490 |

.257 |

.307 |

.441 |

0.9 |

-0.4 |

4.65 |

5.92 |

| José Rodríguez |

.239 |

.346 |

.398 |

.231 |

.309 |

.413 |

0.7 |

-0.5 |

4.04 |

5.60 |

| Brock Stewart |

.250 |

.344 |

.429 |

.208 |

.284 |

.347 |

0.5 |

-0.2 |

3.18 |

5.22 |

| Anthony Banda |

.224 |

.302 |

.355 |

.261 |

.346 |

.451 |

0.6 |

-0.5 |

3.93 |

5.74 |

| Edgardo Henriquez |

.253 |

.361 |

.434 |

.208 |

.300 |

.344 |

0.5 |

-0.3 |

4.03 |

5.49 |

| Nick Frasso |

.257 |

.342 |

.426 |

.256 |

.328 |

.442 |

0.6 |

-0.4 |

4.44 |

5.69 |

| Peter Heubeck |

.246 |

.360 |

.413 |

.250 |

.345 |

.446 |

0.5 |

-0.7 |

4.98 |

6.28 |

| Antoine Kelly |

.233 |

.338 |

.333 |

.245 |

.355 |

.434 |

0.3 |

-0.5 |

4.52 |

5.86 |

| Carson Hobbs |

.277 |

.368 |

.506 |

.211 |

.294 |

.322 |

0.2 |

-0.4 |

4.03 |

5.29 |

| Christian Romero |

.301 |

.382 |

.540 |

.241 |

.312 |

.379 |

0.3 |

-0.6 |

5.11 |

6.07 |

| Patrick Copen |

.233 |

.344 |

.425 |

.259 |

.385 |

.413 |

0.6 |

-0.8 |

4.96 |

6.19 |

| Paul Gervase |